Brad Blackwood mastered the recording of my friend Brandon Herrington's band's Fast Planet at his studio Euphonic Masters. The sonic quality was incredible! His mastering production skills were clearly at work, producing a fine-sounding product that is now available on the market. Brad Blackwood began his professional recording career as a staff engineer at Ardent Studios, Memphis, Tennessee [Tape Op #58]. He gradually gravitated to mastering when he found the precision of product refinement more suited to his particular expertise and interests. Brad was awarded a Grammy for his work on Allison Krauss' Paper Airplane album. Brad has also worked with Maroon 5, Three Days Grace, Korn, Black Eyed Peas, the North Mississippi Allstars and many others. He has received 12 Grammy nominations, two Latin Grammy nominations and 15 Dove Award nominations.

Why are recordings "mastered"?

It's the last creative step in the process of making a record, and the first technical step to producing a mass-produced consumer product. Originally mastering was literally making the masters: it was cutting the acetate to make plates from. Then in the late '60s, Doug Sax started the Mastering Lab. Before that mastering was done by all the labels in house. Doug started doing it and set the bar really high. He also had developed a lot of custom equipment to produce masters. Over the years it became creative processing and more about translating a cohesive feeling across a recording. It's about translation; you want to make sure that whether it's played on an iPod or over the radio it sounds as good and as consistent as it can sound.

In any media...

Yes. It's just a matter of translation more than anything. You want to make sure that you're listening in an environment that you know very well, so that you know what it's going to sound like when it's played in those different sonic environments.

So your mastering philosophy is...?

If anything, it's hands off. I'm a minimalist. I try to do the very least I have to do to make the recording sound as good as it can sound. Some guys use lots of color; I don't. My entire chain has been designed and custom built for the purpose of being as sonically neutral as possible. I don't want it colored or anything unless the recording really needs it and if that is necessary we have the ability to do it. But I try to leave no fingerprints on it if all possible. Now, it usually takes some processing but I try to be neutral. It's considered pretty old school the way we do it.

A typical mastering session consists of...?

I find that you can only hear the recording for the first time once. So I get that initial objective, the gut response. What does it feel like immediately? What sticks out? What sounds good? What doesn't? The system I've built is about efficiency. I want to spend the least amount of time to get the best possible sound. It doesn't mean I rush through it, but the more you listen to something and the more you become accustomed to the way it sounds the more you lose that (initial) perspective. So I don't like to listen to material ahead of time unless a client is worried about the mix. I want to make sure the balances are okay, but I want to listen to it fresh while I'm working on it and work quickly and not drag it out, because I don't want to become accustomed to hearing the "works", if you will. Basically, the session is that. We'll cut the record in a day, then upload reference files for the client to download. If we need to tweak it, we tweak it, if not we cut the parts whenever they're ready.

You started as a recording engineer?

I started in high school working with friends' bands. I didn't play an instrument, but I was always the guy that knew hi-fi and stereo equipment, so I would cobble stuff together and we'd record. I ended up attending Full Sail and after graduation got a job at Ardent and moved up here [to Memphis]. The first couple of years I thought I really wanted to be a recording and mixing engineer, but it was a bit excruciating listening to somebody try to hit a guitar part for an hour and a half. Sometime in the late '90s Ardent bought a SADiE system; it was when SADiE had just started. It's a digital editing system and mastering platform. I learned it inside and out and became the guy for all the editing. Gradually that just kind of slowly morphed into, "Hey, why don't you do some EQ on this..." which I did under the guidance of John Hampton [Tape Op #92] and John Fry. Those two have just a ridiculous amount of experience and talent between them. They did more to shape the way I hear things than anybody else. Hampton was more hands on — I worked with him everyday and he was more of an influence. Hampton was always good about sticking his head in and hearing something and saying only a little word or two. I'd think about it for a second and go, "Oh yeah. He's totally right." He's got the ears for that. Those two guys taught me how to listen. That's basically my entire job: I get paid to listen to music.

What formats do you master?

We do digital of course, but we also do 1/4-inch and 1/2-inch analog. I love the sound of analog. I don't know what it is, but for the most part it seems like material that comes off analog always sounds good. There's no question that the flexibility, efficiency and speed with which you can work off digital files is just unparalleled. It takes a lot longer mastering a record off analog than it does a digital. We also have different digital sources. A vast majority is PCM (Pulse-Code Modulation) but we do get some DSD (Direct Steam Digital) material in as well, and that's almost like a different ballgame.

What's the difference between the two?

Well, it's a type of PCM , like a wave file, but DSD is really just a one bit signal and uses pulse-density modulation encoding. It gives you a really wide bandwidth and so it's the closest to what came off the console.

You "restarted" Ardent mastering. How did that come about, and what was the attraction in doing so?

In the mid '80s Ardent Mastering, as it existed, was operated by Larry Nix. Ardent felt like mastering was kind of dying off. They basically sold it to Larry and he started L-Nix Mastering. When I got there, it was a separate entity. So, one day Dana [Key], who at the time was one of the owners of Ardent Records, said, "Why don't we just let Brad master this record and see how it turns out". Everybody liked it and it just opened the floodgate: probably 25 percent of my late '90s mastering work was Ardent Records. I was already mastering pretty much full time then in the little copy room, which was my mastering room. I went to full time mastering in late '98.

Was Ardent Mastering more digitally oriented than analog?

Yes, from a source standpoint. It's been that way my entire career. We had some analog material, but most everything at Ardent was mixed to DAT or [Alesis] Masterlink. When clients brought in tape I'd pull out one of the machines and use that, but for the most part it's always been mostly digital. We (re)started Ardent Mastering in '98, and I ran it until '03 when I decided it was time for me to do my own thing.

And you have been here in your studio for the last...

Just over ten years.

I've read that you worked with Jim Dickinson [Tape Op #19], Jim Gaines, Skid Mills and others who were centered at Ardent. What did you learn from them related to mastering?

Dickinson was the first one. Everyone of them brought something different to my world view and perspective of how I need to hear things and my to approach to mastering. For example, Dickinson was a very artistically minded person. He didn't care very much about the technical aspect of things. For him it was about the vibe and the feel. It's very easy for mastering guys to get caught up in the technical aspect of it and forget the music; the love of the music and how cool different textures are. Dickinson kept me focused on that. Jim Gaines was just such an accomplished mix engineer. Throughout the '80s and even the '90s he had so many huge hits that he mixed. He had really great ears. He was one of those guys who wasn't afraid to push the boundaries. "Let's try a little bit brighter. Let's try a little bit darker." He was very artistic but he understood the technical aspect of things very, very well. Skid was a big rock guy at the time. Today he's doing a little bit of everything, but throughout the late '90s and all through the first ten years of the '90s he focused on rock 'n' roll; I mean just straight ahead rock. I've said for years that I think that the big heavy rock is probably the hardest thing in the world to mix and master, because everything is at 11 and everything takes up all the space. The drums are huge and big and the guitars are huge and big. Getting the sound to be "natural" is difficult. Skid is just so amazing at capturing that. He was my most challenging client for the longest time, because he knew what he wanted it to sound like and I had to figure out how to get it there. I love working on rock stuff, but I think those big, gigantic produced rock records are really hard to do well.

When you are mastering a project are the artists in the room with you?

No. I don't do attended sessions at all. If I know somebody really well, someone that I've worked with for years and years, maybe I will; but generally no. Attended sessions take longer and cost the client more, because there are usually more revisions. People have always had this mindset that when you show up and you're there, you can get it right the first time.

Not true?

No. The reality is, this room sounds ridiculously good, but every room has it's own sonic imperfections. I found once I said "no more attended sessions" that it was easier to meet client's limited budget restraints with a lot fewer revisions and delivering a higher quality product.

So artists don't meaningfully contribute to what you are trying to accomplish?

Honestly, not when they're in the room and unfamiliar with how it translates, in my experience.

Your studio is very nicely designed. Who designed it and what are it's special features making it a "mastering studio?"

I designed the room myself — I know just enough about acoustics to get myself in trouble. I did some mode analysis of the room and discovered that the dimensions were actually really good. After working out here for a couple of years I noticed the bottom end just wasn't quite right. I found myself having to figure out ways to make sure I had it exactly right. So I talked to Thomas Jouanjean at Northward Acoustics in Belgium. He came in and did a few detailed changes: the front wall, removed some bass trapping, and then rebuilt the entire rear wall using his own custom absorption material. The difference was just absolutely astonishing. Now I'm at the point where I can hear something and react to it immediately. There's no guessing whatsoever, which is really important to me.

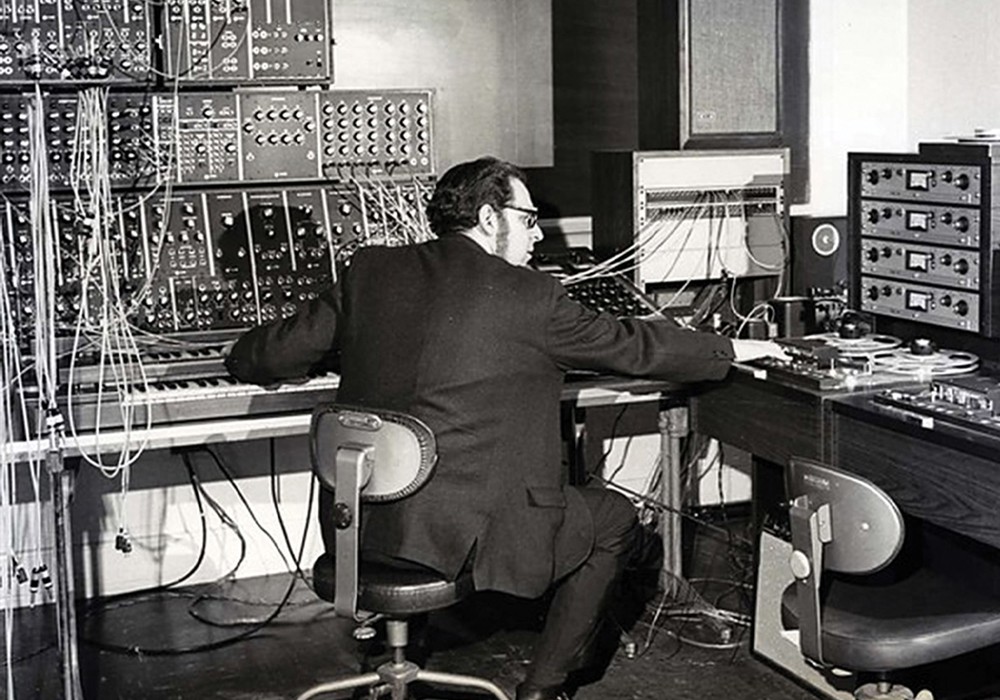

Your studio is full of custom gear. Who designed and built it?

All of it was built by Frank Lacy down in Oxford, Mississippi. I do have a Barry Porter EQ design, nicknamed the Net EQ, that I had Frank build. It's just a fantastic EQ. My newest piece is a really unique 3 dB per octave capable hi/lo shelf unit that Frank Lacy built. Another custom piece of gear is the Daveilizer; a Dave Collins design from when he was at A&M Mastering. It's a natural, very clean sounding equalizer. I also have a Crane Song Ibis, actually the first Ibis Dave Hill ever made. It's a mastering version that I use that as my dedicated mid-sided EQ.

How did your work with Alison Krauss come about?

That was primarily through Mike Shipley. Paper Airplane was my second with her — I did a greatest hits album with her. There have been a number of Alison Krauss and Union Station "Greatest Hits," but they were always compiled by labels or management. This was the first one that she went through and picked out each one of the songs. We re-mastered everything from the ground up. She was very happy with the way it turned out. Then Mike cut the record and they brought it to me. I was thrilled to do it because they are absolutely astonishing musicians.

Tell me about mastering or "re-mastering" the Emerson, Lake & Palmer records...

We mastered two of them for iTunes. The first [sef-titled] record and Tarkus. That was really cool. I'm an old classic rock head, and just to be able to work on that stuff was amazing.

How did that come about?

That was a relational thing because John Kaplan, a good client of mine, recommended me to Pete Giberga, the director of A&R for Razor and Tie. I got an email from Pete's assistant asking do you want to do some "ELP" stuff. It was like, "Is that really a legitimate question? Are you kidding? Really?" I had to type out my response to be sure they meant "Emerson, Lake & Palmer."

What new projects do you have in the works?

I just cut a new single for Jane's Addiction, which is cool. I was a huge Jane's fan back in like the '80s and early '90s. I think it really shaped a lot of the way I listen to rock music. I just did the Korn record with Don Gilmore. Cutting the new Lamb of God. A bunch of cool projects like that.

Your list is very diverse.

I love the fact that I get to work on a little bit of everything. There are some guys that master records that get pigeon holed. "If it's rock, we'll use this guy or if it's a blues record we'll use..."

You're not there yet.

I hope I don't ever get there. I don't want to be that guy. I want to be open for any project... in the meantime I'll keep listening to music.