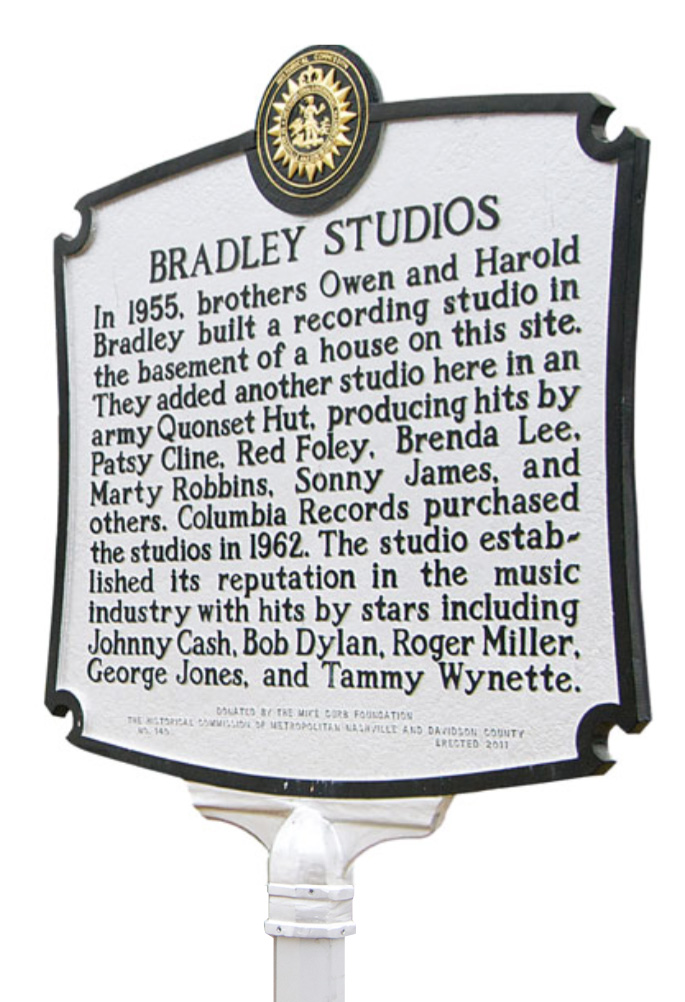

Nashville has long been considered the capital of country music. Owen and Harold Bradley helped make that possible when they opened the Bradley Studios in the '50s, in the heart of Music Row. After adding on the Quonset Hut Studio, they ushered in a style of country music that crossed over in the pop markets, with songs like Patsy Cline’s "Crazy," Brenda Lee’s "I’m Sorry," and Bobby Vinton’s "Blue Velvet." When Columbia Records bought the studio in the 1962, the hits continued with artists like Johnny Cash and Bob Dylan.

I had the opportunity to talk with the current studio manager, Luke Gilfeather, as well as drummer Kenny Malone, bassist and producer Norbert Putnam, and engineer Lou Bradley, to discuss the history of the studios and the Nashville music business in general. Kenny Malone has been a session drummer since the '70s and continues performing and recording today. Norbert Putnam was a member of the original Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section, as well as the "Nashville A-Team," before switching to producing acts like Joan Baez and Jimmy Buffett. Lou Bradley started working at the old Columbia Studios in the late-’60s until they closed in 1982.

How long have you been working here?

I’ve been here just over a year.

I heard that this is the original archway of the Quonset Hut, and that the rest was built around this studio.

Well, there was initially a house on 17th Avenue here. This was a residential area, and two brothers, Owen and Harold Bradley, bought the house in the mid-'50s with the idea of starting to record people here in Nashville. They took the first floor out – so it went straight down into the basement – to give a bigger recording area. They started turning hits out of there almost immediately. They were running out of room, and looking to expand into making short motion pictures, like variety TV shows. They went out and bought an Army Quonset hut for $7800, and attached it to the back of the house. The house then got torn down when Columbia Records came in and built Columbia Studio A around it. That’s why it’s so convoluted getting around in the hallways.

And now Belmont University owns it?

The Mike Curb Family Foundation owns it, and he lets Belmont use it. Mike Curb actually owns a lot of the buildings around Music Row. He owns this one, RCA Studio B, and the Masterfonics building. He’s letting Belmont use this one for, I think, the next 50 years.

What about the gear that’s used here? Is any of it from way back when?

Not here, unfortunately. All the stuff is more modern. There’s nothing from that era. There kinda is, but it came from Bradley’s Barn [Studio] and the RCA complex. The Mike Curb Family Foundation bought a collection of microphones from the Bradley family, and they are all classic.

Like '50s and '60s microphones?

Yep. There’s a pair of Telefunken 251s and four Neumann M 49s. Ten RCA 77s and three RCA 44s came from the RCA studios but are here now. That’s the only thing that really comes close to the era. We really don’t have anything from the Columbia Studios era. Supposedly, the fuzz tone was invented in the Quonset Hut. They were using a tube console, and Glenn Snoddy – who was an engineer here in the early days – noticed that a grid in the console had fused together, and somebody was playing a guitar through that channel. The guitar player wanted to fix it, but the producer told them to wait, and ran the solo through it. Glenn Snoddy reverse engineered it, and found out what happened. He ended up developing [what became] the [Maestro FZ-1] Fuzz- Tone pedal, and sold them the license. It was on the Marty Robbins tune, "Don’t Worry."

That’s interesting! What console are you running for the Quonset Hut?

That’s a 24 channel Neve VR. It doesn’t have automation; that’s been stripped out of there. We use it for teaching inline consoles. That was actually a project from the Belmont maintenance class. They found that thing on the floor of a warehouse just stacked in pieces, and they reversed engineered the metering and some of the center section. There are student signatures on the back from those who helped put it back together. It’s a good teaching tool.

What about this place do you think made the "Nashville Sound?" This is kind of where it started; here and the studio in the original house.

I think it was kind of a concurrent development between the Bradley brothers and the RCA studios across the street. They were trying to compete with rockabilly and rock 'n’ roll music. They had a bunch of country artists signed to these labels, who were selling in the thousands. Roy Orbison and The Everly Brothers were selling close to a million copies. Owen and Harold Bradley – and Chet Atkins across the way – started thinking of ways to attract a broader audience. What they ended up doing was taking the fiddles and the steel guitars and downplaying them. They started using things like grand piano, which had never been used on country records, and background singers and lush string arrangements. I...