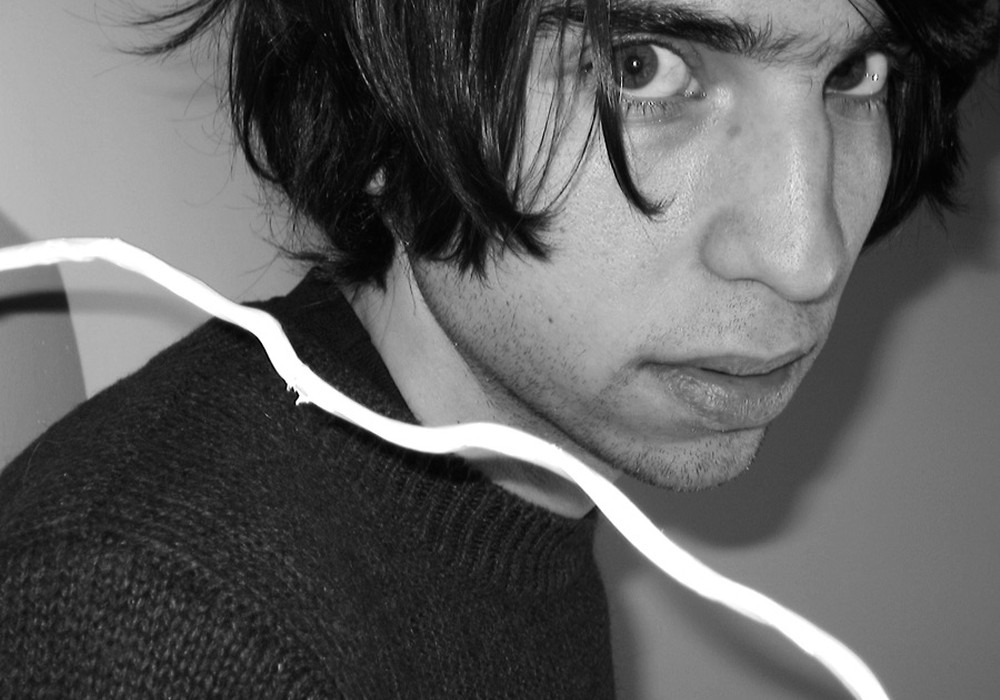

Gus Seyffert may not be a household name, but his behind the scenes involvement would make you scratch your head and wonder why. From playing live and/or in session with The Black Keys, Norah Jones, Roger Waters, and Sia – to producing and engineering artists like Beck and Michael Kiwanuka, Gus has contributed significantly to the sound and spirit of many great records. As we sat down in his Echo Park studio in Los Angeles and chatted, it was crystal clear that he didn't arrive where he is by sitting around waiting for something to happen.

Can you tell me a little bit about your early interest in music?

I grew up in Kansas City, Missouri. The government was doing an experiment on our school system to try to integrate the schools, and they had a magnet school program. In middle school I went to a performing arts magnet called Kansas City Middle School of the Performing Arts, KCMSA. I'm dyslexic, and I always struggled in school. I did just about everything I could to get out of doing anything academic. I took classical guitar, was in an orchestra playing upright bass, played in the jazz band, and took recording studio class – all at a pretty young age. KCMSA had a Tascam 388, so that was what I learned on. It was there I met my still best friend, Jake Blanton, who's a great musician.

What music were you listening to?

Jake and I were both obsessed with The Beatles. This is before they released all the CDs in the '90s, so nobody in our class really knew who The Beatles were. Vanilla Ice and MC Hammer were popular. I guess I didn't totally realize that there were different generations of music. I'd go to school and they'd be like, "Check out Vanilla Ice!" And I'd say, "Check out The Beatles!" They'd say, "What are you talking about?"

Where were you getting information on The Beatles?

Those were the records that my parents had in the basement. Oldies 95 FM [KCMO] was my station. From a young age it was Motown, The Beatles, '70s rock, and music like that.

What do you think was the attraction for you?

You know, it's hard to say. Now I think, from the perspective of where I'm sitting now, I could rattle off, "Oh, it was a live band, or it's tape, or the recording process was different." It was just a connection to the music. It sounded good, and made me feel good.

At what point did you start dissecting it from a production and recording angle?

I think it was when Jake and I discovered the early Paul McCartney records and realized that he did everything himself. When we got access to the 388 it was mind-blowing. Jake was really good at playing all the instruments. I always tried to do that, but couldn't do it as well. The school would let us take the machine home over the summer, and that's when we started writing and recording our own music.

Did you have anyone to show you the recording ropes?

We were really lost. Kansas City, at the time, was not a very hip town. We had something like a [DigiTech GSP21] Legend effects processor, and were like, "What is this thing, and why does everything sound like shit?" We did recordings on the 388 with about three mics. We'd tape one mic to the ceiling so it was hanging down, like a little mono overhead, and then another one on the kick drum with a pillow in it. When we were a little bit older we got some money together to go record at a studio in Kansas City that we knew. We recorded to [Tascam] DA-88s through a pro Tascam console. I don't know how many mics the guys put up on the drums, but we did this whole recording and it was like, "Wow, this is terrible." I think that's when it finally snapped for me. There was something that we were doing before that worked better for what we were trying to do.

That's advanced thinking for that age.

Yeah, exactly. I think that's been something that's kind of followed me along.

You started your music career as a bass player.

I started young, working as an acoustic jazz bass player in Kansas City. I went down about a ten year "jazz guy" road where I didn't want to play electric bass. I wanted to play swing. I went to CalArts and studied with Charlie Haden, moved to New York for a short while trying to do the jazz thing, and then came back out here and decided I wanted to transition into a different style of music. At that time in...