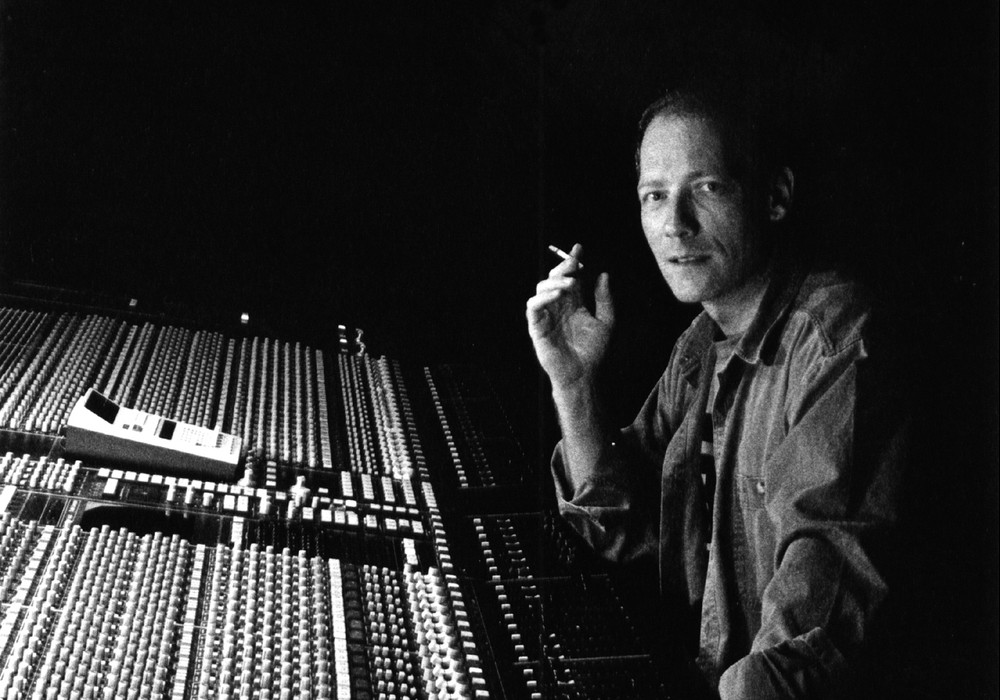

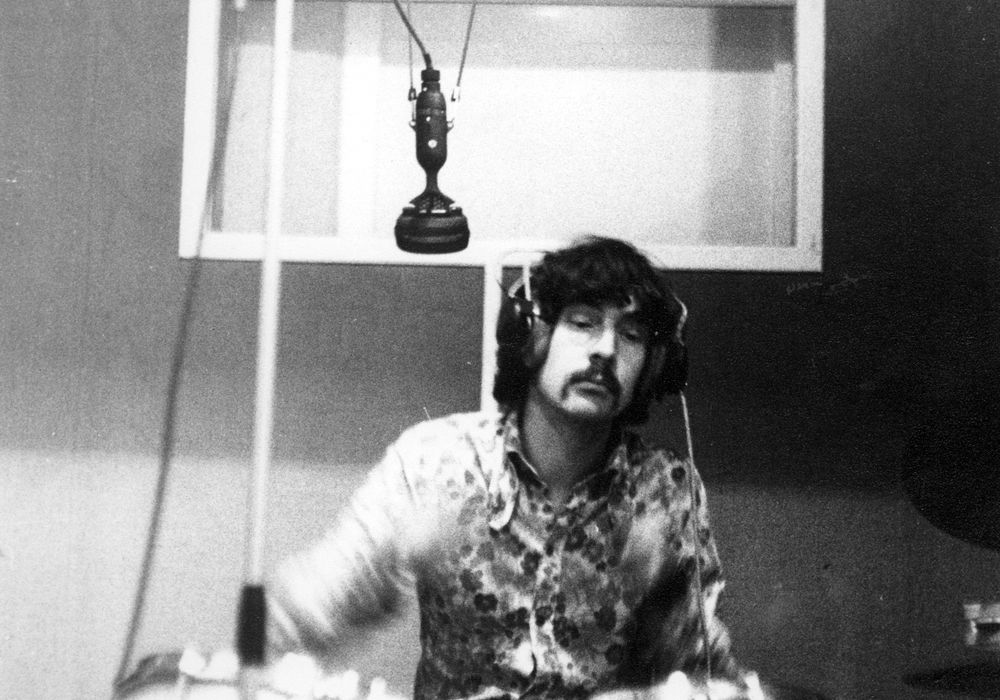

Over the last 20 years Matt Chamberlain has contributed to a staggering variety of recordings including David Bowie, Tori Amos, Frank Ocean, Miranda Lambert, Bill Frisell, Brad Mehldau, Fiona Apple, and Edie Brickell & the New Bohemians, to name a few. Seriously, we're just scratching the surface! I first met Matt in 2003, when we were studio neighbors in an old warehouse in Seattle's SODO district. I would show up to work, stand in the hall listening to him play, and think, "Yep, all the things they say about him are true." His space was packed with many drums, noisemakers, and recording gear. I'd seen Matt's weird kit combinations online, and was always inspired by his approaching each project with a clean slate, as well as an openness to experimentation. Recently I was working on some music with Dave Matthews, and when we needed drums it seemed like a great opportunity to give Matt a call. When I arrived at Matt's studio, Cyclops Sound in Van Nuys, California, it was a familiar sight. Loads of drums, noisemakers, pieces of metal to hit, gongs, and a ton of great recording gear. We chatted during breaks, over a couple of days of tracking, about drums and recording.

Tell me about your studio, Cyclops Sound. I know there's a little backstory here.

I moved down from Seattle at the end of 2010, and I was looking for a place, because I'd had a studio in Seattle. I tried recording in a couple rehearsal facilities next to speed metal bands, but it didn't work out. I was talking to my buddy, Jason McGerr [drums, Death Cab for Cutie], telling him I was having a hard time finding a space in L.A. and he said, "I think our singer, Ben [Gibbard], had a space over in the Sound City complex and has left." I called, and it was totally empty; a 1,000 square foot space! I snagged it, and I've been here for four years now.

It was already built out by Ben?

Yes. Thank you, Ben!

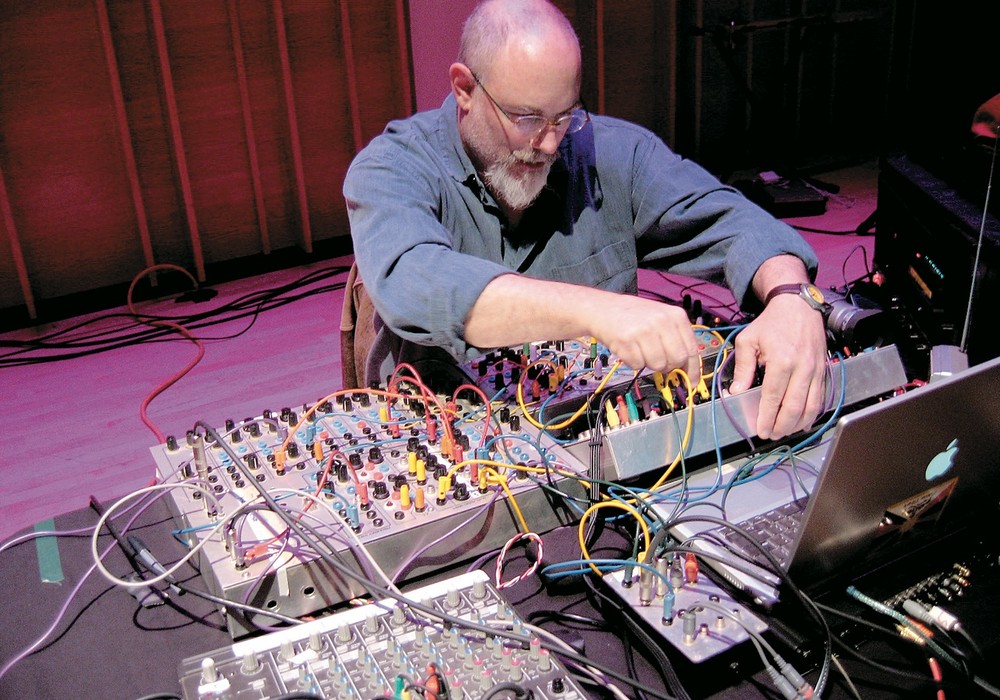

People send you sessions to track drums on here. Has that become the norm for you?

Luckily, I still get called to play on records in other studios, but 25 to 30 percent of my work is here. It's mainly a producer coming over with an artist – maybe a bass player – and we'll track the rhythm section to what they have in Pro Tools. That's a lot of it. When they send me a song and say, "Do your own thing," those are actually the hardest, because nobody's here to answer questions. I have to get them on Skype or email, so it takes a little bit longer. I engineer those, so I'm over by my kit with screen share. It's a lot of work, and it takes me out of the headspace of just playing.

Did you learn engineering by doing it? Or did you have friends, engineers, and producers help you along the way?

Both. On sessions, I'm always driving the engineers crazy, asking them questions. If there's a sound I'm really digging, I'm always asking them, "What are you doing?" Most of what I learned early on was from working with Jon Brion [Tape Op #18]. He's such a gear nut. I learned so much hanging out with him and talking about gear. Learning the history of "what this mic does" or this compressor or that mic pre. Over time, I would think, "I like that drum sound, so I should buy that piece." By working with different people, I learned different things.

Jon Brion has obviously been able to marry the gear to the music. Buying a piece of gear doesn't mean anything; it's who's driving.

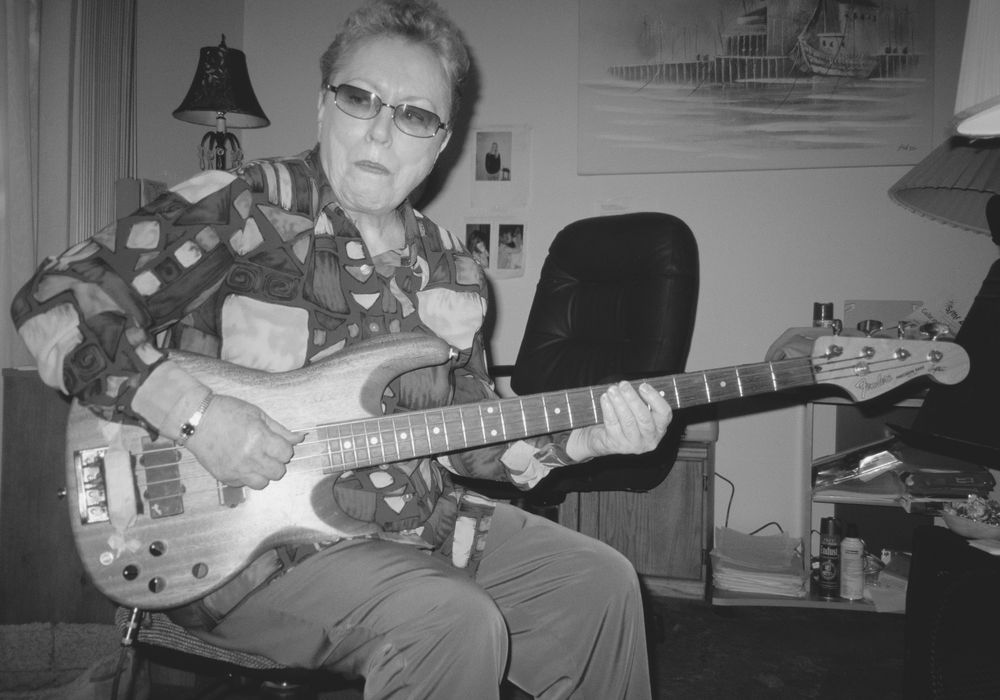

Especially with drums, it's the source. Whatever the source sounds like, that's what it's going to sound like. At least that's what I think when I'm recording with people. I try to make the drums sound – to my ears when I'm sitting behind them – the way that a mic would hear it. If the snare drum is super ring-y, I'm assuming the mic is going to hear that. Over time I've learned that's not necessarily true, but with real close mic recording it is. It makes sense. If the mic is right on the drum, it's going to pick up whatever's there, depending on the way you hit it. Obviously, drummers are all different. Everybody has a different balance to how they hit the cymbals, toms, and snares. You can get away with minimal mic'ing if you're the type of drummer who plays with a good balance and you're not bashing your cymbals. The one mic that we used on the majority of what I've done with Jon Brion is a [Telefunken ELA M] 251. It's like drummer's perspective, by my ear. If you have it on the right side – if you're right-handed – it's the perfect situation. It takes a general picture of the kick and snare, and it's beside your head so it gets the hi-hat out a little bit. Then you fill it in with all the other mics. That's the theory with that kind of recording, but it's a very specialized type of drum recording that he does. Most people want a stereo image, so they'll put up stereo overheads and do the kick thing where you have the inside kick,...

_display_horizontal.jpg)