John Hardy runs The John Hardy Company out of the basement of an old and pretty house in Evanston, a few blocks north of the Chicago limits. His M-1 preamp uses a transformer-based, discrete solid-state signal path to produce its famous clean sound. I stopped by his house to tour the facilities where he builds pre-amps and runs his small company. I got to see his vintage Hammond organs (while not a very active musician, he'd rather be known as a bass player) and discuss the merits of soda in glass bottles. In the midst of all that, Hardy found the time to share some stories about himself, the M-1, and the company that bears his name.

"I can remember doing just some crude recording of bands that I was in, mostly just a couple of microphones or something like that. I might have had a Shure mixer at some point, something like that. Of course wondering why this didn't sound at all like it's supposed to sound — the usual chaos and confusion and gross stupidity as you start off not knowing a thing. Little by little you learn, for example, that gee, there is such a thing as a low- impedance microphone. Not all microphones have a quarter inch phone plug at the other end of the cable. So we all learn little by little. I was playing in bands; I was doing a little bit of crude recording with the bands. I was, in my own stupid way, building speaker cabinets and learning how to make them better and better as time went on. And working on different electronic projects, and I built a four channel tape recorder back in 1969. It worked occasionally. Little by little, you know. You blow things up, you learn from that. Electrocute yourself, you learn from that. Little by little you learn, hopefully you learn. Hopefully you don't keep electrocuting yourself every day for the rest of your life."

"It's just more of a hobby really. I was lucky to get out of high school at the rate I was going. I was well on my way to crashing and burning. Fortunately graduation occurred before the plane hit ground. I think I had one semester of high school electronics and that was the limit of my formal education. But there are other ways, and little by little, you learn this, you learn that, trial and error, talking here, talking there, talking to whatever, magazine subscriptions" all provide useful information. "Some of the semiconductor manufacturers are just, they're willing to give you a world of knowledge just in their data books. I have to show you my library where there's just book after book, free books from National Semiconductor or Analog Devices or whatever." I later saw the library, where bookshelves full of manuals and other electronic information occupy most of one room in the basement. "So there is much to be learned, various textbooks that have come out, so that's how little by little..."

"The first major project of any kind that I had done, I think, would have to be a couple of consoles that I built for dB Sound, based here in Chicago, back in 1977. Those consoles were specifically done for the group Kansas. For some period of time, dB had been working with the group Kansas, before Kansas was a real big band. The way I understand it, when it came time for that fall of 1977 tour, Kansas said to DB Sound, we're a bigger group now, we're getting bigger exposure. You've got to upgrade your equipment. I had done some smaller projects for dB at different times, and they came to me and said, 'We'd like to do a console, and we'd like you to do it.' In the fall of 1977, miraculously, two consoles got built, a front-of-house and then a stage mix console. The main modules for those, I built as modular as I could. There was a particular module common to both consoles that had the line input section, the mic preamp section, and an equalizer, all in one module. I called it the IM-200 module, just the Input Module, IM-200. Rationality at work there — simpler to remember what they are. Some of those modules have been made available as sort of vintage Hardy equipment or something. Oh, jeez, the nightmares I could tell you about that whole project, but at any rate they're still around. In fact, I've got a box of about 8 or 10 of them under that table over there that one of the guys who is still involved with dB sound, Harry Witz, wants me to fix. So I still will fix them; I'll offer repair services for people that have those. Even though they're 22 years old at this point, I'm happy to keep them running as much as I can. That was my first real, substantial product or project but that was fall of '77." At that point, Hardy still used monolithic op-amps.

The January/February, 1980 issue of the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society included Deane Jensen's article about the JE-990 Discrete Operational Amplifier. The article contained specifications for the op-amp and directions on how to build it. Jensen stated, "The circuit is 'public domain' and can be used for any purpose without license or permission." Hardy felt that "Deane had this great circuit design for the 990," so he began building 990 op-amps. In 1981, Hardy began making the MPC- 500 mic pre-amp card, a replacement card for MCI 500 series consoles. It included the 990 op-amp. "I became aware of the Jensen JE-16-A input transformer. And it was originally only available in a round can, which made it larger in diameter than a square can would be, length and width. So I bugged Deane long enough and I suppose some other people did too, to make a square can version, so it would be more space efficient. That made this card possible, because otherwise there wouldn't have been enough height for a round can to be sitting in that opening. This is a direct plug-in for the MCI 500-C and some of the D series consoles. Just plug it in and you're done." Hardy followed it with the MPC- 600 for MCI 600 series consoles and then the MPC- 3000 for Sony MXP-3000's.

While the good feedback that he received pleased Hardy, he was surprised by just how much his preamp cards pleased some people. At the time, there were a lot fewer mic pre-amps available than there are today. "I don't know when the Massenburg came out, but the Massenburg and maybe the Sontech by Burgess MacNeil, but there were maybe a couple of others. Maybe the API pre-amps might have been available in some kind of somewhat usable form back then." With fewer options to choose from, some people who "were either crazy enough or dedicated enough" added boxes and power transformers to convert them to stand-alone preamps.

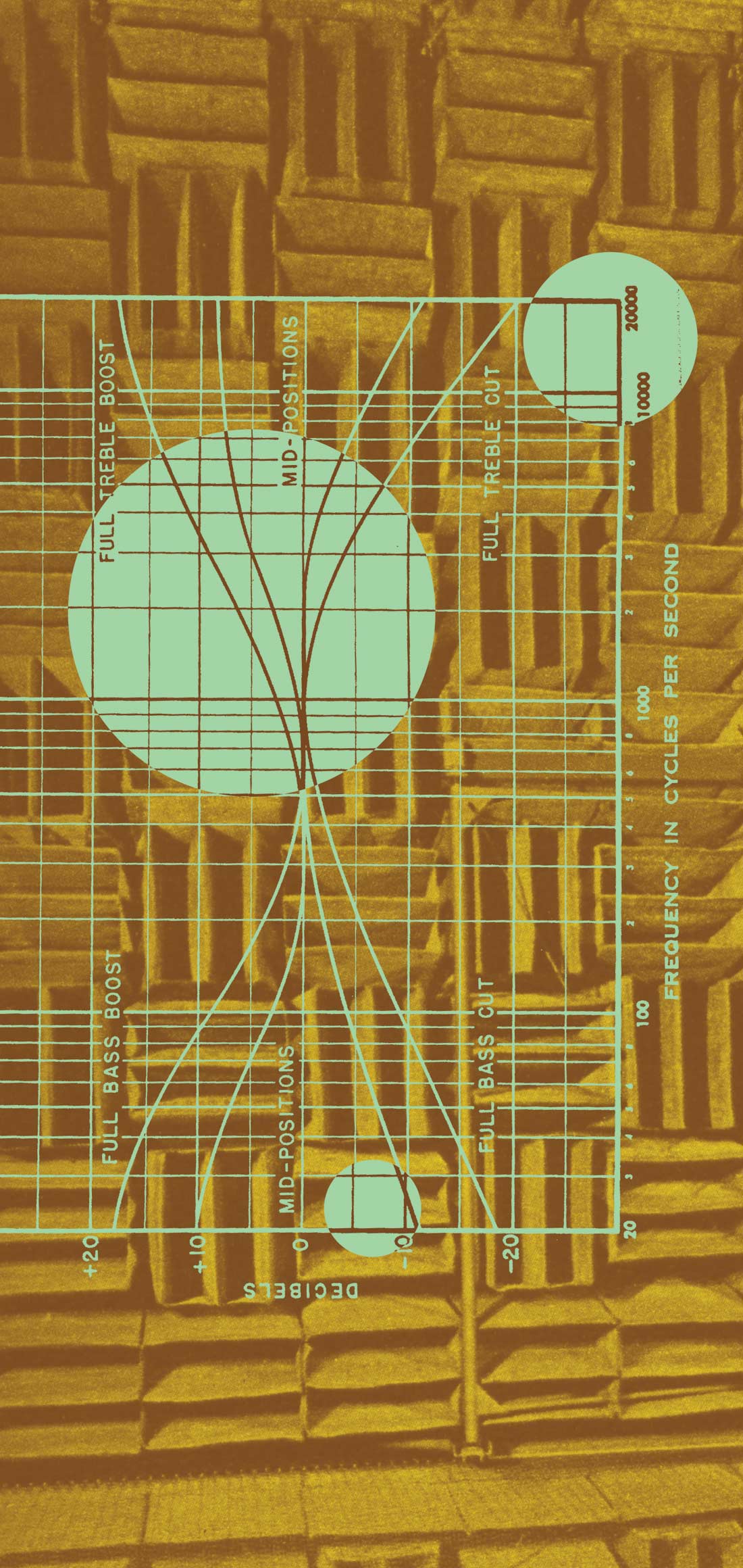

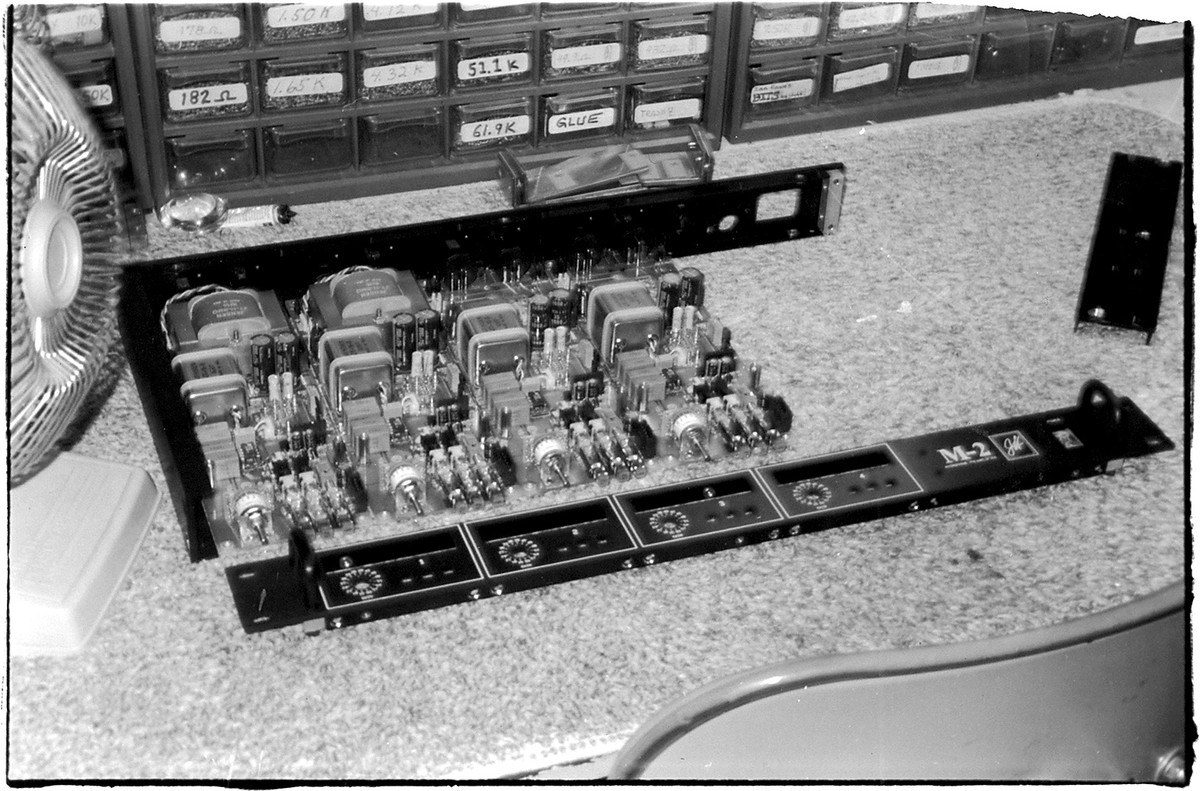

Hardy applied the basic design principles of his replacement cards to build the preamp for which he's best known, the M-1, which he began selling in 1987. "There are three main things that show up in my various ads for the product. The first thing the signal sees when it comes in is the JT-16-B input transformer, which is the top of the line Jensen input transformer. I just think Jensen makes the absolute best audio transformers, and this is their best mic-input model. So the signal first sees the transformer, then it goes into the 990 discrete op- amp. The third feature is that there are no capacitors, coupling capacitors, anywhere in the signal path. Capacitors can cause problems; they can cause degradation to the signal. There's a problem with capacitors known as dielectric absorption. A capacitor is just two conductors separated by an insulator. Literally, speaker cables are capacitors; they are also resistors, and if there's any kind of curve to them they're inductors I suppose. There's always an insulator between the plates. Now you can get capacitors that have Mylar as the insulator, or polypropylene, or polycarbonate or polystyrene, or Teflon or this or that or on and on. And then there are the larger electrolytic capacitors, which still have an insulator, but it gets into a whole different territory. The dielectric can actually absorb some of the signal as the signal moves from one plate to the other. You want to block the DC voltages; that's the main reason for using them in a signal path — DC voltages will creep in and you want to stop that. So the capacitor blocks the DC but lets the AC through. But that dielectric in the middle there can absorb a little bit of the signal and then release it a short time later, and that can cause a little bit of smearing of the audio signal. It's better or worse depending on the type of capacitor. I know there are all kinds of transformer-less mic preamp companies out there, and they would probably say 'oh, transformers, you know, they're terrible, all sorts of phase shift and ringing and core saturation.' Sometimes it comes down to, well, who's got the biggest problem, is my transformer a bigger problem than your capacitors? So I'll just leave it at that. Your mileage may vary." He feels that the Jensen JT-16-B which he uses in the M-1 "belongs in a category all its own. Part of the deal is it's not whether it's transformer-less or transformer-coupled, part of the deal is, 'how well is the design executed.' That's true in so many things in life."

"When I first started making the M-1 mic pre-amps in 1987, I just crossed my fingers and hoped that anybody would even kind of like them. And it just seems that most people like them a lot. I've heard some people tell me that they have many pre-amps to choose from, but they find themselves going back to the M-1 much more often than any other preamp. So many people, they're beating their heads against the wall, trying to get things just to sound right. I remember bringing an M-1 to a local studio in the earlier days of the M-1, and the engineer, Danny Leake, he's a local engineer here in Chicago and he's got an excellent reputation. He's traveled around the world doing all kinds of things. He was expecting me to bring an M-1 up, and I brought it up. He was in the middle of doing some vocal overdubs. This was at Universal Recording, while they were still in existence. He was using one of these legendary old Neve consoles that everybody seeks, and thinks it's the greatest thing to come down the road. So as soon as I walked in, he stopped the vocal overdubs, he patched the microphone into the M-1. Instead of being in the old Neve and a Pultech equalizer-he had been using this combination of the Neve and a Pultech equalizer to get the high frequencies back where they belonged after the old Neve had screwed them up. So he listened to the M- 1, he said, 'All right, take '71 or whatever. The vocalist was singing, and after about 8 seconds, I heard Danny say 'Whoa.' And that was his way of saying whoa; this is just great, just by itself. This is so much better than the old Neve and the Pultech equalizer. People are just looking for; I think 97% of the time they just want things to sound the way they sound. And the M-1 seems to do a much better job of doing that than most pre- amps. Everybody is entitled to their opinion, everybody can get the kind of sound they want to get."

"Another quote was 'Even the producer could tell the difference.' I like to poke fun at producers, you know. A true story, a long story but a true one, where even the producer noticed when they switched from the M-1 back to an old Neve in fact. A whole other story where it was an M-1 and an old Neve. So, to make a long story short, an M-1 failed. The engineer called me in a panic. I sent him a new 990 because I figured that was the problem. Gets off the phone realizing that he's not going to be able to use the M-1 for the rest of the day. So he plugs the stuff back into the old Neve, which was one of the reasons they went to this particular studio in New York, A&R Studios. And called everybody back in, they started recording. And everybody, including the producer, noticed the difference, and they refused to continue the session until the M-1 was fixed. So you know, there's an example of an old Neve."

"I keep thinking of Blind Melon Chitlin, the Cheech & Chong fictitious character. It's this fictitious old blues harmonica player who's just this burned-out, practically just a pile of dust for a human being. But somebody like that I imagine, they probably have some just beat-to-crap microphone they plug into some guitar amp; that's the mic preamp is this guitar amp that's probably 50 years old and the tubes are about to fall out, and everything about it is screwed up completely. And it gives him exactly the sound he's looking for. Well, for something like that, fine. You do the Silvertone amplifier, you know, the Sears Silvertone amp, with a horrible microphone and it's great. But the guy that wants to then record that, if they manage to hire a recording engineer to do this Blind Melon Chitlin album. He might put some fine microphone in front of that amplifier, plug it into an M-1 mic preamp to capture it exactly the way it's supposed to sound. Anything anybody wants to do is fine. If it works, salute it. If it doesn't, you know, try something else. There are only like two or three hundred mic preamps to choose from these days."

"When you get into the details of a discrete design versus a monolithic design, you realize that there is at least a potential for much better performance. Now again, there are better and better monolithic op- amps as time goes on. And there are certainly ways that you could make a discrete op-amp so badly that you'd be better off with a monolithic op-amp. Just being monolithic doesn't mean anything, other than the fact that it's monolithic. It could be bad monolithic, it could be great monolithic. I mean discrete, well, whatever — either way. Evaluate and make up your own mind. But there are lots of reasons why this circuit could be better and in fact ends up being better. I write at somewhat great length in my 990 data package that I include, I explain to people that if you were to look inside of a monolithic op-amp, you would find a little chip of silicon that's typically about a sixteenth of an inch square; that's the whole circuit. And somehow on that sixteenth of an inch square of silicon, they have to put dozens of transistors and resistors and diodes and capacitors and whatever else. And it's amazing that they can get all those radically different kinds of components fabricated on one tiny chip of silicon. Now it starts off with a 6-inch or 8-inch wafer and they cut 'em up into thousands of little op-amps. But how in the world are you gonna get the world's best input transistors, where the signal first comes in, with the very unique requirements that those transistors have," into a tiny silicon chip? "That's a very unique set of parameters to make the input transistors. Meanwhile here are the two output transistors, meant to handle lots of power and whatever, radically different requirements. They're made in a substantially different way. Well how do you get the world's best input transistors and the world's best output transistors on the same 16th of an inch square chip of silicon? It's just... you can't do it. There are going to be compromises. It's like trying to have one vehicle that's both a Porsche 944 or whatever, and an 18-wheeler, over-the-road. So there are going to be limitations in monolithic op-amps, and oh, by the way, you need some real resistors on there as well, and some capacitors. So you certainly have the potential with a discrete op-amp of having much better performance. You can have much higher output current, which then allows you to use much lower-value resistors in the surrounding circuit, which then can give you even lower noise. And just one thing leads to another, and you can get much better performance. The trade-off being it takes up a lot more room, and it's 50 dollars versus maybe 50 cents. But we're not talking about building clock radios for the side of your bed, where who cares what it sounds like. This, in theory, is part of a business where people are pouring their heart and soul into the music that they're recording. And so the difference between a 50-cent op-amp and a 50-dollar amp is not nearly as important to them as it might be to someone shopping for a clock radio for their kitchen or something. They don't want to spend more than 9.95 for the whole radio, much less... You can do good pre-amps with monolithic op- amps, [but] I think judging by the reaction from my customers, this discrete design offers something superior. But again, your mileage may vary and your personal preferences are yours."

"And then vacuum tubes, that's a whole other area, of course. You can get 12AX7 tubes, or ECC83s, whatever, from 10 different sources out there. There's lots of companies that make them now, and each one has its own sound qualities, so how do you deal with that. There are usually coupling capacitors in tube mic pre-amps. I suppose there's a way to do without them, but usually you need them, so there's that potential compromise. And one thing about [the JT-16-B] input transformer, which is a real important point, I think, is that it has a very low impedance ratio. 150-ohm primary, but just a 600 ohm secondary, which is an ideal match for the 990 op-amp. The 990 likes to look back and see low impedance coming from whatever is before it. So that transformer matches perfectly. Well vacuum tubes get their best noise performance when they look back and have a high source impedance." At this point Hardy pointed to a Jensen JE-115K-E high- ratio transformer. "That's the kind of transformer that you would typically find in a tube circuit as well, with a high impedance ratio to match better with the requirements of the tube. The trade-off being you get more voltage gain out of that transformer, you get about 20 dB of voltage gain, compared to 5.6 dB out of this, but [the JT-16-B] will perform in a much more linear fashion. If you compare the specs of this transformer to that transformer, you'll find that this has wider bandwidth, the distortion is lower, the phase response is more linear, group delay, however you want to look at it, better specs — simply because the lower the impedance ratio. Laws of physics at work here — the lower the ratio, the better it will perform. So most tube circuits, I don't want to speak for all of them, but typically tube circuits require a high-ratio transformer. So you've got the compromise of a high-ratio transformer. You've got the variability of all kinds of different tubes out there. You've got coupling capacitors in the signal path, so there are some of the potential problems. Again it becomes a matter of execution and how well somebody does a particular design. But all things being equal, that transformer will perform better. And no capacitors should sound better than capacitors. Again, I don't wanna step on anybody's toes too badly."

"When I was designing all of these things, and really particularly with the M-1 I guess, because that's a ready-to-go product, you don't have to invent your own boxes and power supplies and stuff. So it's the first really mainstream kind of product. I knew that it was a great op-amp and a great transformer, and with no capacitors in the signal path it ought to be beneficial somehow. There are so many great designs that people come up with that just fall flat on their face for whatever reason. It may even be a great design but there's something about the packaging or the look or there's a vibe there. You know, we're dealing with human beings here; you just never know. I've had a lot of people compliment me on the metering of the M-1 for example. That seemed so important to me that, when you've got a signal of some unknown quantity coming into the preamp, this is sort of a great unknown. You really need to know, well how am I doing here? What kind of levels are we dealing with?"

Since when Hardy designed the M-1 he was unsure in what genre it would find its niche, the broad range of styles for which the people use the preamp has pleased him. "One of my earliest customers is a guy who was in Southern California, now he's in Nashville, last I knew — Michael Wagener from Double Trouble Productions. He's doing what I would call, and forgive me if it's the wrong terminology, but heavy metal kind of stuff. You wouldn't want to be anywhere near the guitar amps without serious hearing protection, that just real high level kind of stuff. There's that kind of stuff going on, there are people doing spoken- word, voiceover kind of stuff, talking books. But there are all kinds of M-1s down in the Nashville area. There are people doing classical work, people doing jazz work. You name it. Whatever there is to do, it seems like the M-1 does an excellent job. It doesn't have a certain sweet spot and then everywhere else it kind of falls apart. It just seems to do well whether it's at the lowest gain settings or the highest gain settings or whatever. Again, I had my fingers crossed hoping people would kind of like it, and it just seems like it fits in everywhere, for which I'm grateful."

After Hardy designed the M-1 preamp, "Deane Jensen asked me if I'd be willing to build his concept of a preamp, but using my packaging as the basis for it." The joint collaboration resulted in the Jensen Twin Servo mic preamp. "On the Jensen there are two 990 op-amps per channel, whereas the M-1 uses just one. For two or three years, I sold that directly to Deane Jensen and then he would market that as his own preamp. But sadly Deane died after a couple of years of marketing [it]. And after a few years the folks at Jensen finally said to me, the people who took over after Deane passed away, they finally decided, well hey, you're the mic preamp guy, why don't you sell the Jensen twin-servo mic preamp? We're up to our necks in transformer orders. We do transformers; you do mic pre-amps. So we'll sell transformers. I certainly tip my cap to Deane Jensen. He was extremely helpful over the years. I certainly miss him, and I think the industry as a whole misses Deane Jensen and his contributions."

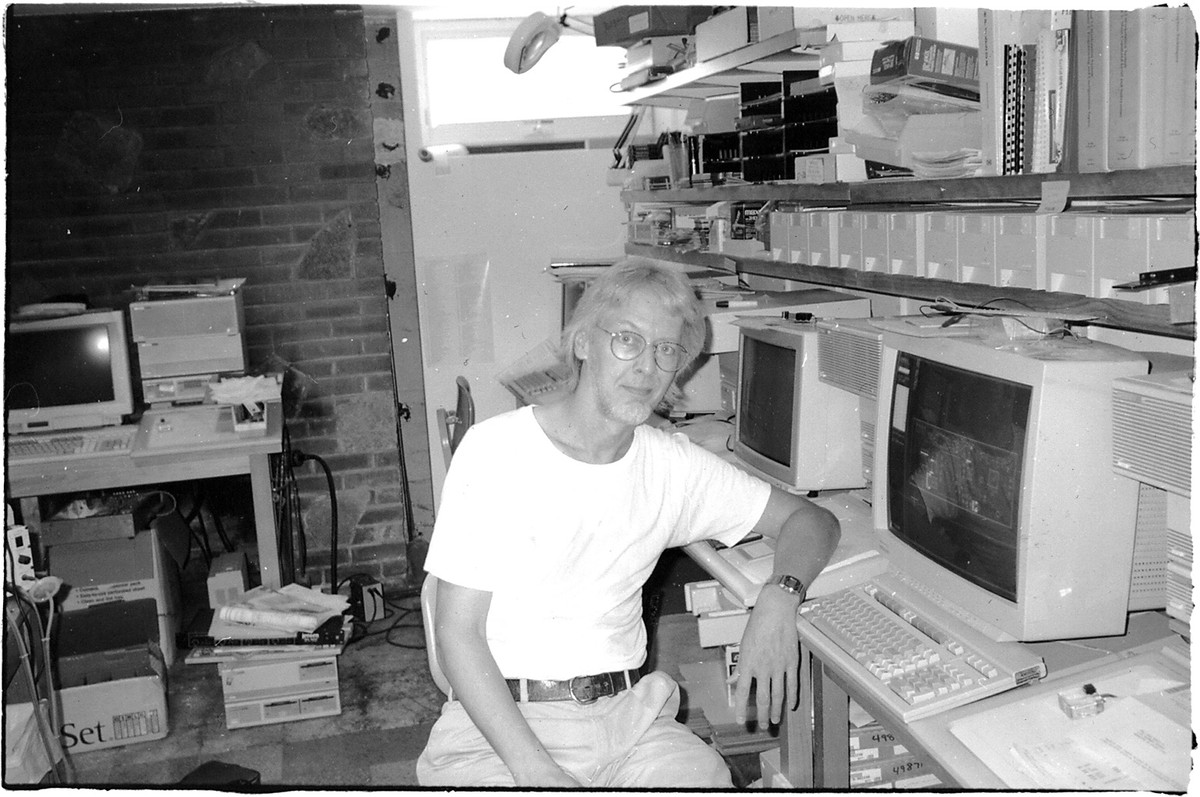

Hardy designs his pre-amps on old Hewlett Packard 300 series computers. "A guy I used to be in a band with back in the early '70s, at some point in his life decided to write a CADD program." Hardy wouldn't name the ex-bandmate, because he abandoned the program over ten years ago. The anonymous programmer started the CADD software in the late 70s, before personal computers, so he wrote it in the native Hewlett Packard Pascal environment. Today, Hardy runs it, and maintains it himself too, on several Hewlett Packard machines, which he can buy used for affordable prices. He showed me some of his current designs in the CADD program, ranging from re-worked versions of his old replacement cards with better grounding patterns to a redesign for one of the bedrooms in his house.

Hardy finds running a small audio company challenging but worth the effort. "It's frustrating and there are so many things that divert me from designing stuff. I'm behind on things I'd like to get designed. But I certainly like it a lot — I mean, I don't think I would trade it. I was in enough bands where there were insane people in the bands generally screwing things up and causing chaos, and working for other people at various points, that I just decided I've had enough. I'm gonna just do my own thing here and call it the John Hardy Company. And that way I don't have to answer to anybody, I don't have to drive to work because I work here, and I like it a lot." In addition to selling Hardy's preamps, the company also distributes a German direct box, the AMB Tube-Buffered Direct-Injection Box.

He has a small staff helping him. "Just a few people, part time people that do assembly work. And I let them do as much as I can, but when it comes to the final testing and quality control and everything, that's what I do." His employees install the cards and the chassis, attach the knobs, and cover the unused areas with blank panels. "But then I come in and start neatening things up and give it a good inspection and some last little bits of soldering I have to do. And then power it up and make sure that everything is working right, calibrate and test it. Stick it in a box and ship it out, hopefully to a customer that will live happily ever after and love it for years."

"As I'm designing more and more pre-amps, at least until I see some reason to change, I will be using those same basic ingredients. I'll have different versions of it, for example [a preamp with] a variable high-pass filter. I've had various people say, 'Well the M-1 is great, I wish I had a mixer, it's like an M-1 with pan-pots, maybe and a high-pass filter' — So a high-pass filter. I'll probably add a switchable resistive pad on some models, whatever I come up with in the future. Offer more choice, but still based on the same basic principles, the same transformer, same op-amp. Variations on a theme, yeah — if it ain't broke, don't fix it."