Robyn Hitchcock has long been one of my favorite artists, whether it's the spastic psychedelia of his former group The Soft Boys or one of his many solo records, there's always great songs with catchy melodies and dada-esque lyrics. When an opportunity to interview Robyn came up I decided I'd ask him about using lots of different studios, sessions and musicians on his new CD, "Jewels For Sophia," and get some facts about the recording of some of my favorite albums of his, especially I "Often Dream of Trains" and The Soft Boys' "Underwater Moonlight." He was a charming interview and the show he played, with Tim Keegan's band and ex-Soft Boy/Katrina and the Waves guitarist Kimberley Rew was quite fun. Thanks to Lindsey Thrasher for accompanying me to the show!

I wanted to start by asking you about the new record. It was recorded in different places.

Three songs were done in Seattle, two were done in London [at Milo Studios] and the rest were done in Los Angeles.

I noticed in Moss Elixir too, that you also had a kind of pattern of going different places to record.

I've always liked moving from one place to another. It has nothing to do with the technical quality of the studio — it's simply a psychological thing. I think if you get locked into doing a record for three months, you completely lose perspective of what you're doing. You drag your friends in and they say, "That's very nice, do you want to go out and have a pizza?" Or you take the tapes back home and you listen to them while your blind drunk and think it's great. You're too close to the project. For the last two A&M albums, there wasn't enough time between starting the thing and the final mixes to assess them. At the time I thought they were great, but that's just because I became a part of the collective hypnosis of making a record. Prior to that (except for an album I did called Groovy Decay, which was similarly done in one sort of spate and I also thought was disastrous) I've always done things in bits and pieces — right from the Soft Boys up to Queen Elvis. We tended to only work in one studio in one town, we had certain haunts. But it was all in little bits so you can listen to what you're doing, take it away and live with it for a couple of months and then go in and overdub and mix it. You really appreciate it.

Make sure it's the right basic take of the song.

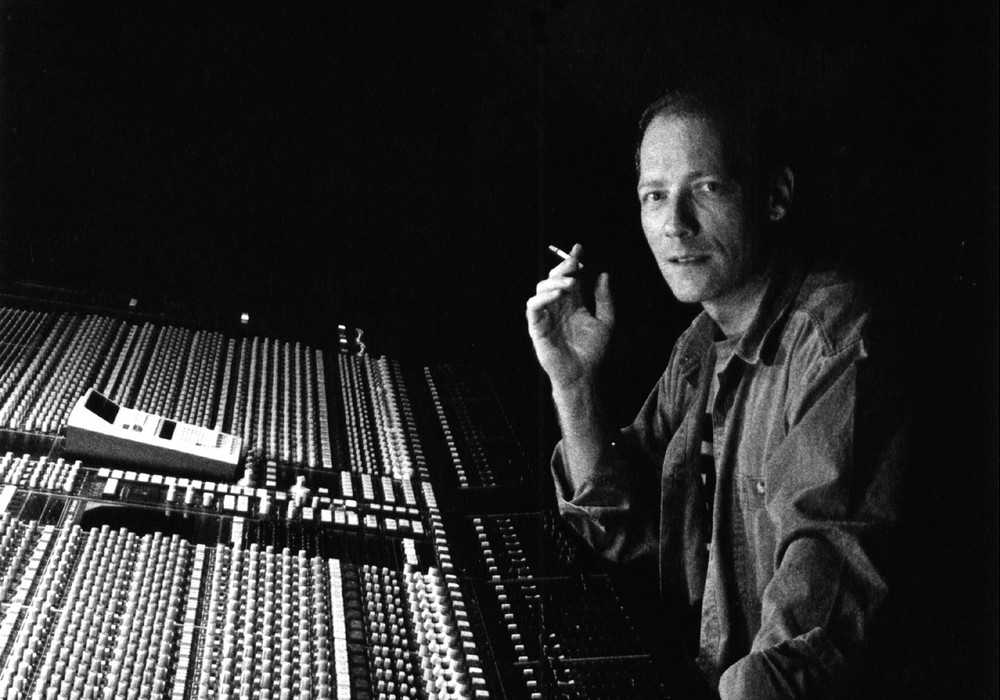

Yeah. It's also like having hundreds of children, you can't focus when you have twelve songs running around your heels. You're just trying to get them in order. If you've got just three songs, you can cherish them more. It's just more exciting — I appreciate the recording process so much more if it's broken up like that. With the most recent records, I know people in studios all over the place. I can't afford to fly the Young Fresh Fellows over to London, but I can afford to fly over and record with the Young Fresh Fellows, or go record with Grant Lee [Phillips] and Jon Brion [#18] in LA for a week. It's just fun to have different people. I wouldn't have wanted to make this record with any one set of people. The whole thing, especially at this stage, should just be fun to make. I'm not looking for any other element — if there's fun on tape, then it should come through to the ears. I think this record is one of my enjoyable, confident records. It's not as somber, it may be the songs, but it's also just the fun of it.

I was surprised to hear a song like "Viva! Sea-Tac". It feels like an exuberant, off-the-cuff rock song. It something that you can obviously do, but it doesn't always come out on your records.

I actually wrote that song in London, but it was obviously a good candidate for recording with them [Young Fresh Fellows] in Seattle [at Hanszek Studios].

I wanted to throw a few different names at you, from different people you've worked with in the past. One of the most obvious would be Pat Collier.

Pat Collier sidled up to me in 1977 after a gig somewhere. I remember he came up to me in a club and said, "I saw your set and I kind of like it." I thought, "This guy's very suspicious." It turns out that his father was a policeman. About two years later we started working in his studio — it was very cheap. He also understood how to make really great 4-track recordings by bouncing things down. He was a real student of the '60s, he wasn't part of this "Steve Lillywhite" 24-track thing. We were just scuttling away in this dank sort of...

_display_horizontal.jpg)

_display_horizontal.jpg)