We interviewed Phill Brown in issue number 12 of Tape Op. Over the years he's worked with some of the greatest artists ever, like Jimi Hendrix, Joe Cocker, Traffic, Spooky Tooth, Jeff Beck, Led Zeppelin, Robert Palmer, Bob Marley, Steve Winwood, Harry Nilsson, Roxy Music, Stomu Yamash'ta, John Martyn, Little Feat, Atomic Rooster, and Talk Talk. This is an excerpt from his book, Are We Still Rolling?, and we'll be running more chapters from it in upcoming issues.

Last issue: Phill recounts the recording of the Rolling Stones' classic, Beggar's Banquet.

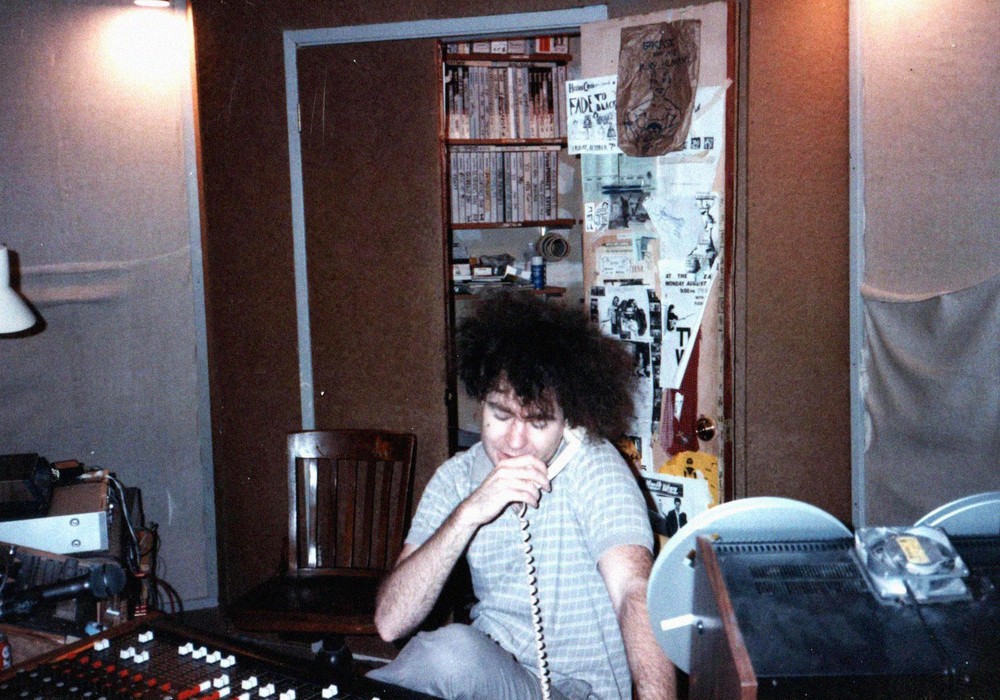

I joined the newly opened Island Studios on the 25th of June, 1970, on a wage of £25 for a 40 hour week. For the first few days I assisted Frank Owen on his sessions. This was to give me time to adjust to where everything was, to understand how the Helios desk worked and to meet the rest of the studio staff. The majority of this staff were aged between 18 and 26 years old, and were a great collection of characters. The atmosphere and working conditions appeared extremely relaxed.

Once I started to engineer on sessions, events happened very quickly. My first session at Basing Street was with Third World War, produced by John Fenton, who also wrote many of the band's lyrics. John was about 5' 10" in height, 28 years old, and was bright, speedy, and anti-establishment. He had a skin-head hair cut — a style that was extremely unfashionable in the music scene of 1970. He had made money, both from his involvement with Seltaeb (the Beatles merchandising company of the mid '60s), and from Eran Schroeder Publishing. Third World War had been formed in 1968, at the height of "flower-power", with Fenton eager to work on something he described as "new, positive and aggressive". On day one of the recording sessions, with a joint in his hand, he looked me straight in the eye and announced, "I'm fed up with all that love and peace shit and then having them massacre four at Kent State University. Look at the deaths of Janis Joplin, Brian Jones, Otis Redding and Hendrix — it's all the Rock 'n' Roll/CIA/Johnson/Vietnam conspiracy. I want a no-bullshit, working class band — I've had enough of all this pseudo-peace crap."

I thought, "Ah. Here's a calm, reasonable fellow who has a definite opinion, smokes dope, is left-field and obviously likes to control situations. This could be fun." I liked John immediately and we got on very well.

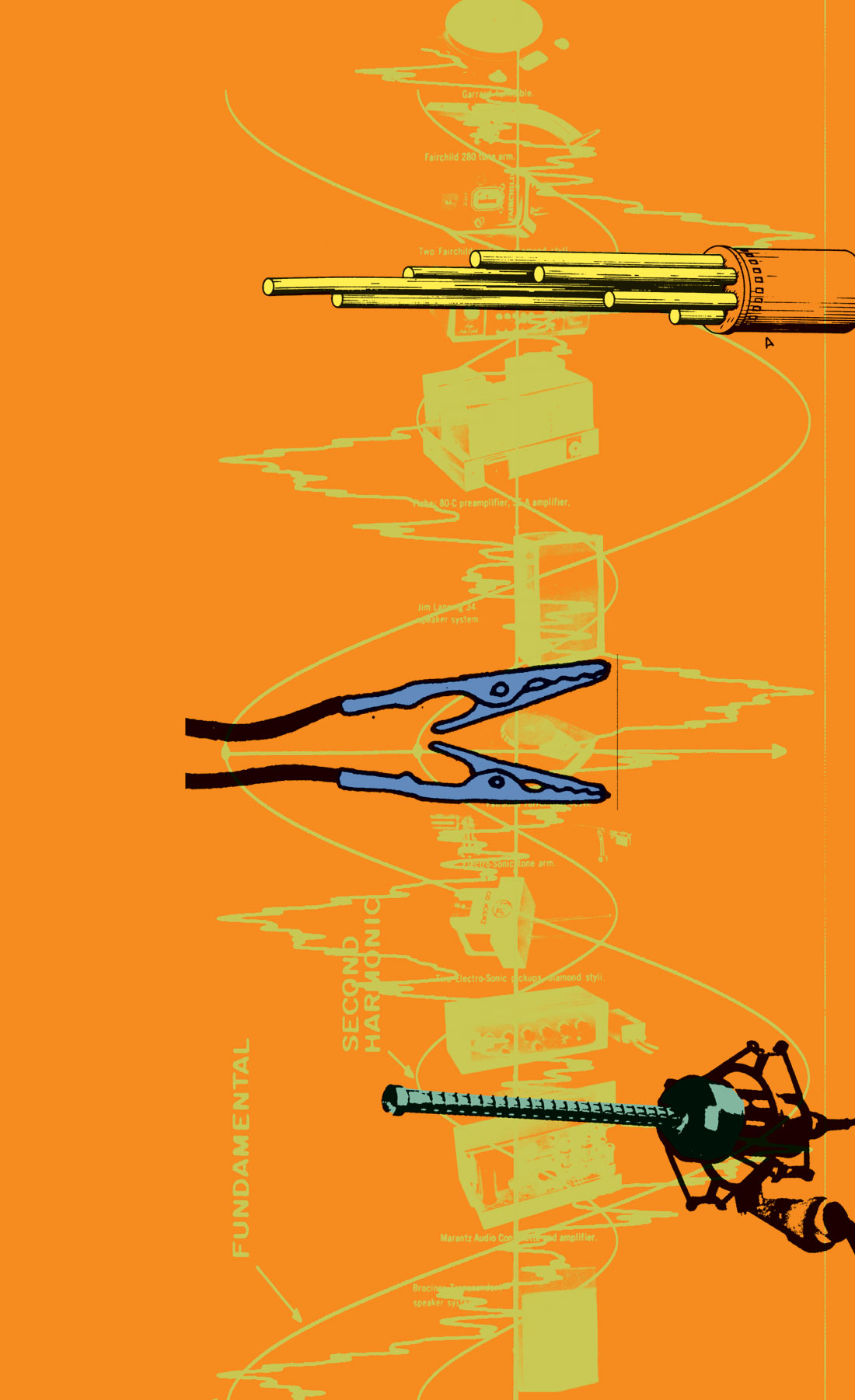

The band set up in Studio 2 with instruments all over the place. I used a selection of microphones that I was familiar with from my work in Canada. These included AKG D12, AKG 224, Neumann U87 and Shure 57. John did not believe in screening people off, so they just set up wherever they felt comfortable. The band consisted of Fred Smith — drums, Jim Avery — bass, Terry Stamp — singer and "chopper" guitar, and Mick Lieber — lead guitar. In addition there were some heavyweight session musicians including Jim Price and Bobby Keys — brass, Tony Ashton — piano, and "Speedy" — percussion. Terry, the singer and band leader, was a 15-stone lorry driver. He played the guitar by smashing the strings with his fist. The music was raw, noisy and uncomfortable to listen to, but at the same time I found it strangely addictive. The band were a real bunch of characters, dedicated to having a good time. They also, whenever possible, liked to shock. The songs they recorded had such titles as "Preaching Violence", "Shepherds Bush Cowboy", "Toe-Rag", "Ascension Day" and "Teddy Teeth Goes Sailing". I thought John's general approach, and particularly his lyrics, were excellent. With hindsight, Third World War were probably the first "punk" band — unfortunately six years too soon — but with more melody, coherent lyrics and musicianship than would have been required in the punk era.

I got into the sessions easily — I loved the material and John's attitude. There was a large amount of drink and drugs around, and the sessions went on all night. We would start at 2 PM and often work through till 6 or 7 in the morning. I would take a cab home to Hammersmith and play mono copies on my Brennel tape before sleeping and returning to the studio for 2 PM. My tape assistant, Clive Franks, fell asleep at the wheel of his car while driving home one morning and crashed. Fortunately he was unhurt, and was back at work by 2 PM — what a trooper. In a matter of days we had cut all the backing tracks for the whole album. It had a great atmosphere. The whole approach...