There are very few record producers whose names grace large portions of my CD collection, and Tony Visconti is one of them. His production work with David Bowie (including the newest album, Heathen), T-Rex, Badfinger, Thin Lizzy, U2, The Stranglers, Sparks and many more has resulted in classic, great-sounding records, and his arrangement skills have shown up on even more records.

A few years ago I went to listen to a panel of record producers talk about their craft, and, although there were some big-name talents there, the man I had come to listen to was Tony Visconti. During a break in the discussions I nervously handed Tony a copy of Tape Op and said we really liked his work. A week later Tony emailed me saying he had enjoyed the magazine very much (which thrilled me to no end) and we corresponded via email, with me eventually asking him if he would write an intro to the first Tape Op book, which he graciously and enthusiastically did. With Tony being such a great sport we knew he'd be up for a full-on interview, so while at AES in New York last year John and I got a chance to sit down and talk with him.

You've done multiple albums with a lot of artists: David Bowie, Thin Lizzy, T- Rex, The Moody Blues when they re- formed... What do you think it is about you that turns one record into a longer relationship?

Well, I'm an incredibly nice guy, is what it is. [laughter] And I give the artist what they want, basically. I really have little agenda of my own in a production. I'm not out to prove myself. I take pride in what I do and I do what I do very well. My name's not going to be bigger on the album than theirs — I have the ratio right. So, if it's a David Bowie album, why do I want to thrust "Tony Visconti" on that? I'll do what I have to do. I'll play bass, I'll sing backups, I'll play tambourine — which I do all the time. So I've always had a sense that my job is to make that artist sound as great as possible — and they know it. They can see that I'm on their side. The record business has always been putting real unnatural pressures on the artist, and in the whole forest of those people that want to try and influence the artist I'm like the beacon of light. "We can do it your way." I'll have the artist communicate their dream to me and that's the goal. "What do you hear in your head? I can do it." And I really can do most things, in an audio sense. I suppose that's why people invite me back. They see that they have a great ally in me, and a good friend.

You must feel good about that.

I do. I feel great because virtually every artist I've worked with I've maintained a friendship with. There's very few I haven't. Even the hardest groups to work with realized I was on their side. They'd be very defensive at first, like the Stranglers. They said, "We think producers are a load of shit. We're going to work with you because your records sound good on radio." That was the intro, and then two albums later we were good friends.

With a case where it is very difficult and you end up not retaining a friendship, what causes that?

I think one or two times I've fallen out with an artist was when, at the end, they wanted me to do something so ridiculous that it was counter to their interest. One group I worked with wanted so much high end on their mastering that it sounded very, very tinny. And no matter what I did I couldn't convince them to go back and make it fatter. And then one person in the band said, "It's okay, the lead singer is legally deaf," and I went, "Oh no," but, you know, you couldn't hurt this lead singer's feelings. I thought, if this is going to be like the emperor's clothes, you can't talk to this guy one to one, then you can't have an open, honest relationship. So that might be another thing that would split me. But, of course, the third thing is that people just like to move on. You know, Bowie has the right to work with other producers. He worked with Nile Rodgers.

Even during the previous period where you'd worked with him there were times when Bowie worked with Ken Scott and others.

Yeah, he would stagger his producers a bit. On two occasions Ken Scott was my engineer and David would the do the next album with Ken Scott as producer. And then Harry Maslin was my engineer on part of Young Americans and then he [Bowie] did "Fame" with Harry Maslin. On "Fame" I just wasn't available. He had to do that. He called me the night he came home from the studio. I was in London and he was in New York and he said, "It just happened. It was spur of the moment. It was spontaneous, and [John] Lennon and I went in the studio." I said, "Next time that happens, phone me and I'll take the Concorde. I'll pay for the Concorde." But artists have the right to change producers. I have no problem with that.

It seems to me like artists are really looking for someone to help them, and they jump from producer to producer, for different input or different things.

With the Moody Blues, I gave them their first hit in ten years, "In Your Wildest Dreams", so they had to use me again, you know. You can't argue with that. [laughter] And it was lovely working with that band, especially Justin [Hayward]. He's the key guy. You make him happy and it'll fall down like the domino effect. I think the thing we fell out on was — by the third album the band realized Justin was kind of getting the lion's share of the songs. And the other guys started saying, "Seems like Tony is Justin's guy." So then they started using other producers on their third album. It got political. It's bound to happen.

Is part of your job is to keep distractions at bay? To keep the artist focused on a project when they have a lot of things going on around them?

Yeah, if I need to I'll put a block on phone calls. That's what receptionists are for. When you're in the studio — it's really particularly annoying nowadays with cell phones — I've worked with some musicians, drummers in particular, and they're on the phone booking their next five albums. I kind of frown on that. There's a time and place for that. I like to start work around 11 AM and, apart from the lunch break, I like to work up to about 8 or 9 PM with no interruptions. Unless they need to be entertained. Like, for instance, David [Bowie] would like to see 15 minutes of a comedy show if it gets too intense. He carries a library of British humor with him. The latest one is a show called The Fast Show — it's like the new Monty Python. So that kind of diversion's good, if it gets your mind off something that's getting too intense and non- productive. When an A&R man is going to be in the studio, it's a very tense situation. You have to guard yourself. Prepare yourself for the comments you're going to get.

Working with artists and people is a big part of the job. What kind of skills do you use in different situations?

One thing I learned early on is that artists are very insecure people. And you find that the ones with the biggest egos are probably the most insecure and the ego is all front. They don't want to be embarrassed and they don't want to look bad. The first person I really encountered who was like that was Marc Bolan. He knew very little about music, but he acted like he was second only to Hendrix, you know. And with a person like that you're not going to challenge them. You know that they're lying, but you know, the object is to make a great record and you have to do whatever it takes and hug and coddle an artist. With an artist like this, I find that yelling doesn't work, or being honest — you have to lie all the time 'cause they're lying. I think it's the worst thing in the world when someone says, "It sucks, doesn't it. Tell me it sucks" and if you say it sucks, that's the last thing they really wanted to hear. I've learned things like that. You say, "It doesn't suck, it's got the germ of something great in it. It's wonderful. You just have to build upon it." So you have to think of all kinds of ways around it, you can't point directly at it. That's what I've learned. Also, getting a person [to be] very clear about their song. Even if it's a guitar solo and there are no lyrics. Get the guitarist in the frame of mind of what the theme of the song is about, 'cause it will knock down a few other options that they don't need to explore. If it's an angry song, he's got to play angrily, or, ironically, very pretty to counter it, but at least you've knocked off a few options. It's not going to be a frivolous solo. It's not going to be happy, so discuss the subject matter of the songs with the musicians. Especially with the singer. You have to get them [to be] clear that they're telling a story. Like, don't do an imitation of a rock star, don't do an imitation of someone else, but sing the lyrics, really feel what the lyrics mean and all that. Sing through that rather than what you think a rock star should sound like. I've been around guys who think that screaming at the top of your lungs is an emotion. It's not an emotion, it's just screaming at the top of your lungs is all it is. So I like to do that. Sometimes we'll have philosophical discussions. Pete Townshend came to play on this new Bowie album. He had ripped the flesh off his index finger from doing windmills in practice for the VH1 show and he had this big open wound. So he said, "I don't have time to do it here, I'll go back to London, I'll record the guitar there, and I'll send you a Pro Tools file." But even though we weren't going to be present in London, we spoke to him about it, what we thought the track was about, and how we felt the solo should go. And we made him listen to other tracks on the album. So after about a two- hour talk he was totally psyched. He knew what he had to do. There weren't too many options, he just had to go in that direction, the direction we were pointing him. And he went back to London and he played the stuff and sent us back the file and it was just what we wanted. Plus he gave us a bonus. He did three acoustic guitar parts, he didn't want to leave it alone, and we used actually all of them. I find that clarity is good, just don't look at your boots and mumble in the studio. Speak clearly. These people are human, they're insecure. Be their best friend. Be the best buddy they have. Challenge them artistically. Point out where they could play a bit better and all that. I've lost my temper once or twice in the studio and it's been very counterproductive.

What causes that? Or rather, how do you not lose your temper in the studio?

What I'd do is say, "Take a break," or I'll just walk out, say I have to go to the bathroom. I won't really, I'll just go out and kick my car or something like that.

What kind of things frustrate you the most?

A person singing chronically out of tune. And you're punching in, doing 14 takes and even take 14 isn't that much better than take one. You tell them that high note, they're flat, and then it's just like you're in Groundhog Day.

Here we go again.

And you think, you know, "Somebody's got to pull the plug on this because it's not going to happen, and it's going to be me and I'm going to look bad — make them feel bad." Those are the things where I feel like I'm in hell. We're doing the same thing and expecting different results. So that's the hardest thing — the thing that frustrates me the most.

Where do you go in a situation like that? I feel like sometimes I just dread vocal sessions because it's often a battle. What can you do with a vocalist, where there's character there but you're trying to get a better performance? What can you say to them and work with them on?

Sometimes I'll say, "Look it's not happening tonight, it's probably not going to happen tonight, but let's take 15 minutes and then come back and give it one more shot." And they kind of go off... usually when you say that they're in some kind of psychotic state, they are frustrated, they're not feeling too good either. They're dying in there. They're saying, "Why can't I get this?" So you just go off and regroup. While they're in that state they can't think, it'll never come, the high note or the great muse will never come. Usually a little diversion will help. Go off and talk about something. You watch baseball — in David's case a little British comedy. Whatever works. And usually you come back and they're ready to give again. They've cleared their mind, they feel better. I find that works. But what I'm saying is don't stay on it if it's not working. Leave it alone for a while. And also, I think there are time constraints on how long anyone can concentrate. I personally don't like to record over ten hours a day. I know what I do after ten hours I'm probably going to have to re-do in the morning because it's usually shit. It usually sounds awful, especially mixing. If it's not finished yet after ten hours I'm not going to go another two hours. I know when I come back the next day it's going to have too much high end, 'cause at that time of night you lose your high end, you start to compress a little too much.

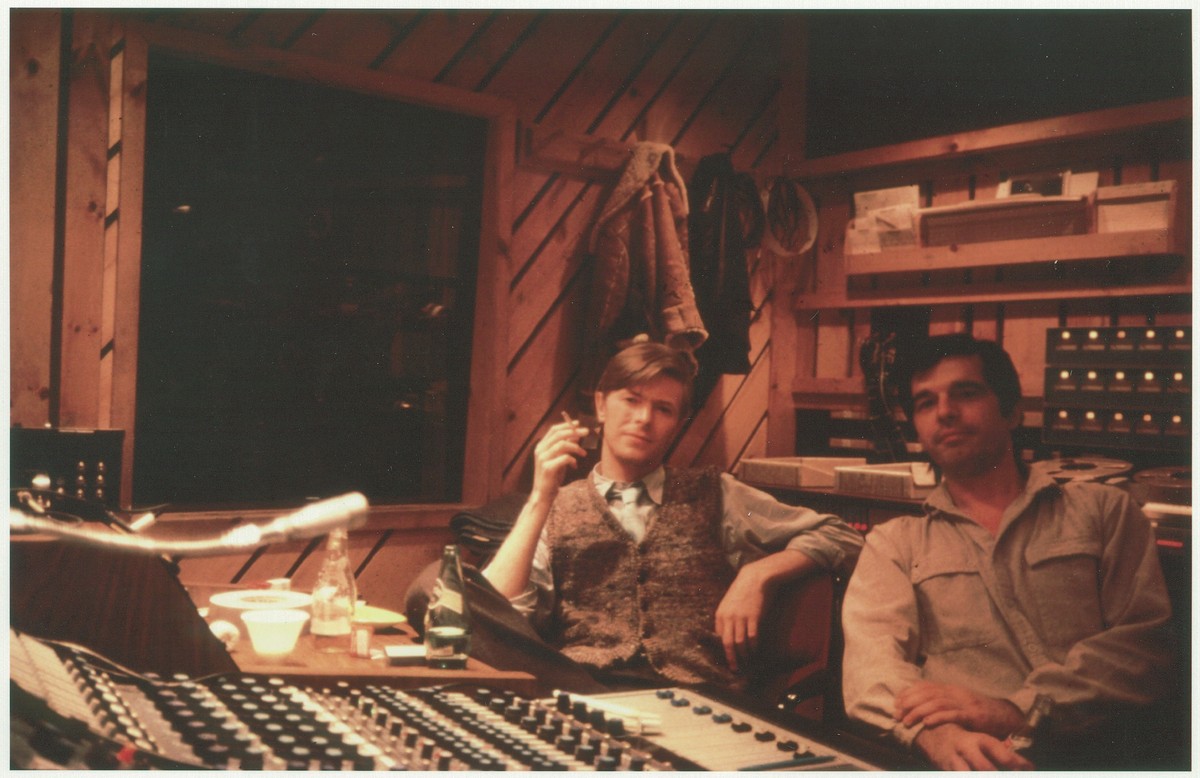

I'm a big fan of Brian Eno's [Tape Op #85] work and the records that you both did with Bowie. It's commonly perceived that Eno produced them, but that's not true. What was the working relationship with all three of you?

How that happened is that one journalist assumed it and wrote it down and then it was repeated many, many times. Both David and Brian put the record straight in subsequent interviews. David went on television and said that I was the co-producer. Anyway, that's water under the bridge, that's all settled. And all they had to do was read the label credits — my name's on the label. Brian and David would conceptualize the album before I came in — they would write together. They spent about two weeks writing. On Low they wanted to know what I was bringing to the table. I said, "I just bought this thing called the Harmonizer and I love it." And they said, "What does it do?" and I said, "It fucks with the fabric of time" and they loved that. I obviously knew how to phrase that right. They said, "Well, bring it along," and they wanted me to recommend some musicians, which I did. So when I met the two of them — we hired this studio in France near Paris, the Chateau d'Herouville — they played what they had, which was very little actually. I'd say all of the songs that eventually had vocals on them had no melody line or lyrics. It was just ideas we jammed on. But I was told to record the jams, which I'd done on Young Americans. Record the jams on 24-track, do it really well. Make sure it sounds good because ultimately every album we did, the demos became the final masters. What I did with that, the difference between that and using a Harmonizer on a snare drum on other albums is that I recorded the Harmonizer live. The drummer always had the Harmonizer in his headphones. And it has some kind of envelope trigger in there. If you hit it harder the pitch will drop off more severely. If you hit it softer it will give you a few little flutters. And Dennis Davis was having a ball with it. He had it in his headphones and he was actually playing the Harmonizer. So if you put a Harmonizer on a snare drum in the mix it's a totally different animal, because it's arbitrary. The drummer doesn't know how it's going to come through in the end. So that was what I brought to the table. Brian was there for the first three weeks. We let the other musicians go after two weeks, Carlos Alomar and the other guys, and then it was just Brian, myself and David doing the ambient side, side two, which was really a three-way thing. I played a lot of those instruments. I was also the click track. It was before the days of SMPTE and any time code and all that, so we just set a metronome clicking and I had to go on microphone and say "One, two, three.." all the way up to like 176. That's how they were writing those compositions. It wasn't even bars, it was just clicks themselves. Which made it more interesting, not working with the framework of bars. So they'd say, "Okay, the synth choir will come in on 86." And that wasn't bar 86, that was click 86. So, that was counting up to a lot of clicks. And that was really fun. Brian, by his own admission, is a primitive musician, so he doesn't know from bars and keys and stuff. He just does what he does and he paints these beautiful aural pictures. And David always loved working that way, with someone who's got a fresh perspective, a fresh view, and he always loved Roxy Music's stuff. Brian left after a week — those ambient things were done in a week. So when it was down to David and myself he would overdub some vocals, some synth, some Chamberlain he used. And then we went off to Berlin to mix it. So Brian Eno never attended the subsequent overdubs, the proper overdubs of the vocals of side one and he never attended the mix.

He was obviously a catalyst for a lot of ideas.

He was a co-writer with David.

That puts it in perspective.

Oh yeah. His input was invaluable. And I could see how people... because the sound was very much his, with his way of working. And I could see where people would confuse that issue. Since I am intentionally a transparent producer, Brian was perceived as the producer.

Thin Lizzy was one band I wanted to ask you about. There was a great piece in Mojo recently talking about the live album and all the replacements going on.

Yes, that's 20% live that album, 80% overdubs.

How did that situation arise?

This is funny. This was in the mid-'70s when I was working all year long and I had certain slots free. So Phil [Lynott] said, "We have to make a new album, what would you prefer a studio album or a live album? The live album's a quickie, the studio album will be two months." I said, "To be honest I've got a Bowie album coming up... I can do the live album." That was a big mistake. He brought all these different tapes in all these different formats. Some were 16-track, some were 24-track, some were 30 ips, some were 15 ips, some were Dolby, some were non-Dolby, and they had all these different concerts that we were supposed to make a live album from. Sorting the best takes out of those was in itself a nightmare, because you'd put the tape up, and you didn't want to realign the machine every time, you just wanted to listen. So we had to do rough mixes of all the performances, analyze them, and when we decided on the takes we were already two weeks into the album. And this is my quickie album. So then we finally got them, and Phil said, "Is that the only one you're going to use, is that the version?" And I said, "Well, we all agreed on it, it's got the energy and all that." And he said, "Well, I don't like my bass on it. I made a lot of mistakes. " Which in truth, because he sang and played bass at the same time, he wasn't the greatest bass player in the world. I said, "Okay, harmless. Let's just replace the bass." So it ended up [being] not just a few notes because I couldn't really match the sound. He's coming out of these Hi-Watt amps on the stage and here he's going to go DI... We even got his rig in actually, and we still couldn't quite match it. So we would replace his bass from beginning to end. And then he said, "Oh, I was off mic and I dropped a few words. Can I replace the vocal?" I said, "Phil this is going to be very hard. Your vocal's coming through the PA system, with the front of house and all that." He said "I'll sing it exactly the same way." And he did, with the corrections. Then the guitar players walked in and said, "As long as you're fixing that my guitar is shite — I wanna redo it." So we did that. Then Phil wanted to bolster the backing vocals, and that was another thing, so they had to come and do that. What we did with the guitars is we did keep the originals, but they were about 25% of the mix and hen about 75% were the overdubbed guitars, which sounded great. It was like a double track. But that album turned out so great, considering all the formats, and it equaled out to one gigantic concert, which it wasn't in fact. It was many concerts, many cities. Partially Canada, partially the USA, and even one, "Southbound," was a soundcheck, so we overdubbed audience.

You worked with U2 on Wide Awake In America — on the live songs on that EP. Yeah.

They wanted to do a live concert — this is years before Rattle and Hum — and they weren't quite ready for a live album. I recorded about three or four shows. I traveled with them on the bus, it was real fun. The purpose of that was that Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois [Tape Op #37] tried to edit "A Sort of Homecoming" for a single and no matter how they cut it it always just never came together. It didn't have the immediacy. It was beautiful, I think, about a 7-minute album cut. They couldn't get it down to the 3 1/2-minute formula. And then Bono said that it was going down live — you know, you record the song and then you do it live for 60 gigs it starts to really sound great. "The audience response has really been great, so we feel that this should be the next single but we can't cut up that album cut anymore. So why don't we record it live?" We got a great recording, but like the Thin Lizzy thing, we took it back in the studio [and] started overdubbing stuff. There must be about five or six guitars on there. I said to Bono, "One reason you're cutting that song up is it's not done in single format — it's not verse/chorus/verse/chorus. It's like 15 verses and then a chorus and then like 18 verses and a chorus." And he thanked me at the end, he said, for teaching him something about songwriting. So that was a great experience. There's a live album in the can that was never released. I recorded many shows.

How much of an engineer are you? How hands-on are you with engineering?

Totally. If I'm working with a big group — and I mean like four or five musicians and they're going to record all at once and I have to deal with five brains — I'll get a guy in to engineer on the tracking. Someone to do that for me. I'll definitely pitch in my views on the sound, but when I use another engineer I respect their space and I don't reach over and push them out of the way and tweak. I say it respectfully, because I know what they're going through too. So it gets that thing out of my mind so I can work with the band and the arrangement. But mixing I invariably do myself. With David, on the new album we wanted to make it the two of us working as a team. We didn't want to have too much outside influence. We had specific ideas and I wanted to do something new with the drums, so I engineered the tracking for this album and I played bass.

Where did you do a lot of the tracking ?

This beautiful studio in upstate New York near Woodstock called Allaire. It's just beautiful. It's built on an estate, which used to be the summer home of the family that owned Pittsburgh Paints. The name of this estate is Glen Tonche and that's what it was before it became Allaire studios. So it's the sprawling summerhouse of this rich Republican family, and Eisenhower and Nixon spent time there as friends of the family. The tracking room was enormous. It was their dining room, and it has shields with armor in there, a family herald shield, and enormous stone walls and a high-pitched ceiling with rafters going across. We hung Earthworks microphones from the rafters, which were a good 40 feet above the console. The console was in the same room as the musicians, so you had to get your sounds on headphones. We used these headphones I was unaware of, Beyer DT150s. It's practically like wearing a football helmet. They really cover your ears and block out external sound, and they're loud and have great low end. So you get your sound on the headphones, and in this case I was working with Matt Chamberlain on drums and then you'd theorize what you think it's going to sound like on playback. It was amazing, I wasn't far off the mark, so I'd just do a little tweaking until we got the sound set up. It took about half a day to get the drum sound. This studio was just amazing and it also had a vibe about it. We were really high, about 2,000 feet above sea level, overlooking this big reservoir. And we'd see hawks in the sky, saw an eagle one day. We'd see deer and wild turkeys and all that. David would get up every morning at six and go in and write that day's work. He'd finish up some of his ideas. And then Matt and I would hit the studio about 10:30 or 11 in the morning and start recording the first song.

Just the three of you? What was David playing?

Piano or guitar. Sometimes we would just record his piano to a click track and then Matt would play to the piano and click track. If it was a complicated piano song, David wouldn't play it live. If it was a guitar song, he would play it live. And I played my bass live, to help Matt out. And then, since I was producing, my bass playing wasn't that great so I'd have to overdub my bass after that.

Clean it up a bit?

Or think of a part. [laughter] So that was a really cool way to work — we did that for a few weeks. Then after Matt left we brought in the guitarist, David Torn. He was amazing. Everyone brought their gear. Matt's gear, it was like a truckload of drums and sampling devices. He has his own world. After we cleared him out we needed that same space for David Torn. He came with so many effects. He needed three tracks to record. He put his effects on two amps (his effects were in stereo) and then his main thing was down the center amp. So I needed three tracks. And if we did five takes of him that's 15 tracks. But it was nice, because I'd only be working with him. Then after we were finished with Torn, in came a keyboard player called Jordan Rudess, who is like this genius wizard keyboard player in the style of Rick Wakeman. He's a neighbor of mine actually [and member of Dream Theater -LC]. He has incredible gear, which was like about 15 Kurzweils and everything. So it was done in layers like that. But the basic was just Matt and David and me putting it down.

In a situation like that you probably have a house engineer?

Yeah, I had a great one — his name was Brandon Mason. We had the luxury of recording the drums on 16-track 2" and flying it into Pro Tools and we did some other instruments on analog tape. I devoted one reel per song. We would record several takes of the drums, up to about three takes for things like guitar overdubs and vocal overdubs, until we'd get to the end of the reel. Matt wouldn't use up all the tracks, we had about ten tracks of drums. We still had tracks left over, though we could record everywhere on the tape. But one reel per song. It was a luxury, but it was a Bowie album. It was the way to go.

Do you have a home studio these days?

I've had about eight home studios and they all start as just something to do demos on. Within six months they escalate into a full professional facility, so.

What's your current set-up?

My current setup is simply Pro Tools, which I use as a hardware platform, but for software I use Logic Audio. A lot of my productions start of with a click track or laying an idea down, then you have the drummer play over that. And I don't think Pro Tools, in it's present form, is very MIDI friendly, very click track friendly.

Do you ever do synthesized arrangements of songs you're asked to arrange to see where it all fits?

I do that a lot. The bands love it. Even if it's stiff. Sometimes they fall in love with the stiffness too.

What was your very first home studio?

My first home studio in Brooklyn was two domestic tape recorders, reel to reels. For reverb I used to record myself in my mother's hallway. My friend built me a primitive mixer, three potentiometers and three 1/4" jacks, and I'd put a mic down at the bottom of her stairwell. I'd be up at the top singing into the close mic and I'd feed in the second mic and I got some really great effects in that hallway. Then I really came into my own. I bought a Panasonic 2-track and it had the ability to do sel- sync. So I would start my production on one track of the sel-sync and then overdub something on track two. I wasn't even thinking about stereo yet. And then bounce that to my dad's Revere, while I put a third element on, because you wouldn't want to waste the opportunity. I'd put something like a tambourine on. And I would bounce that back to another track on the Panasonic, and then I'd have four elements. I'd do that until it would crap out. I got my first production job as a result of doing that. I brought those very same demos to my music publisher, who'd signed me as a songwriter, and then after about six months of frustration he said to me, "I don't think you're a great songwriter, but I love your recordings." And I thought, "I don't understand, what is he getting at?" I didn't even know what a record producer was!