Adam Samuels is Daniel Lanois' [see article this issue] right-hand man in the sphere of sound. His youthful and attentive scholastic approach, hunger and ability to adapt are among his gifts. His almost sudden appearance on the scene also adds intrigue. Though having only been in the business for five years now, he has worked on albums by Pearl Jam (Binaural), Neil Finn (One Nil), Vanessa Paradis (Bliss) and Willie Nelson (Teatro). His engineering expertise can also be heard on Lanois' solo album, Shine. During a break in my chat with Daniel Lanois on the RV, I pointed the tape recorder to Samuels' direction to find just what he is about and to see and hear what makes him shine.

Adam, could you begin by telling us, well, who you are?

I'm 27 [years old] — I was born in Toronto. I started working for Dan about five years ago. A [drummer] friend of mine named Victor Indrizzo was working on a record at Dan's studio. He was my roommate at the time and I wanted to get into recording. I thought I could go to a recording school or I could just hang out with Victor in the studio, so I thought I'd go straight to where it's happening. That was at the Teatro, Dan's studio in Oxnard [CA], and I worked there with Mark Howard for about a year. I started off making a hundred dollars a week — I tiled the bathroom, tarred the roof, got coffee and ended up just learning as much as I could from watching. I would sleep in the studio — it was an old theater so I would sleep down in the orchestra pit. At night after everybody went home I would look around the studio and memorize the names of microphones, the gear and just kind of figure out how everything worked.

That's dedication. So right now you're doing sound on Dan's tour...

Correct — front of house sound on the tour.

And you do everything else, basically, that involves Dan and his music and productions.

I recorded and mixed most of Dan's current record, Shine, and just started a record with Brian Blade a couple weeks ago. A couple of years ago I worked at the Sound Factory as an assistant engineer for Tchad Blake [Tape Op #16 & #133] and got to work on a bunch of records as a second engineer. So mainly studio work is where I like to be, but I enjoy being on the road — it's a very different and new thing to me. You gotta iron things out really quickly and it's a fresh set up every night, which is kind of fun.

It's a great situation you come from and are in.

I am very lucky that I got to learn my way under Dan and Mark and Tchad — I didn't have any sort of classical teaching where I thought that things had to be done a certain way. It leaves me more open to doing things any way — I'm not so precious about specifics — Tchad was like that — when I'd set up a mic for him as an assistant he'd say, "Whatever — put it anywhere" and he would work with whatever I'd set up and would get his sound based on that setup.

If the same kick drum sound sample is used on every Top 40 song, the blame definitely goes on the engineers and producers just as much as the consumers and record company weasels.

You can get good results with anything. Good music, good players, a lot of creativity thrown in — you can make a good record on anything.

So Dan's studio is in his house in Silverlake in L.A.

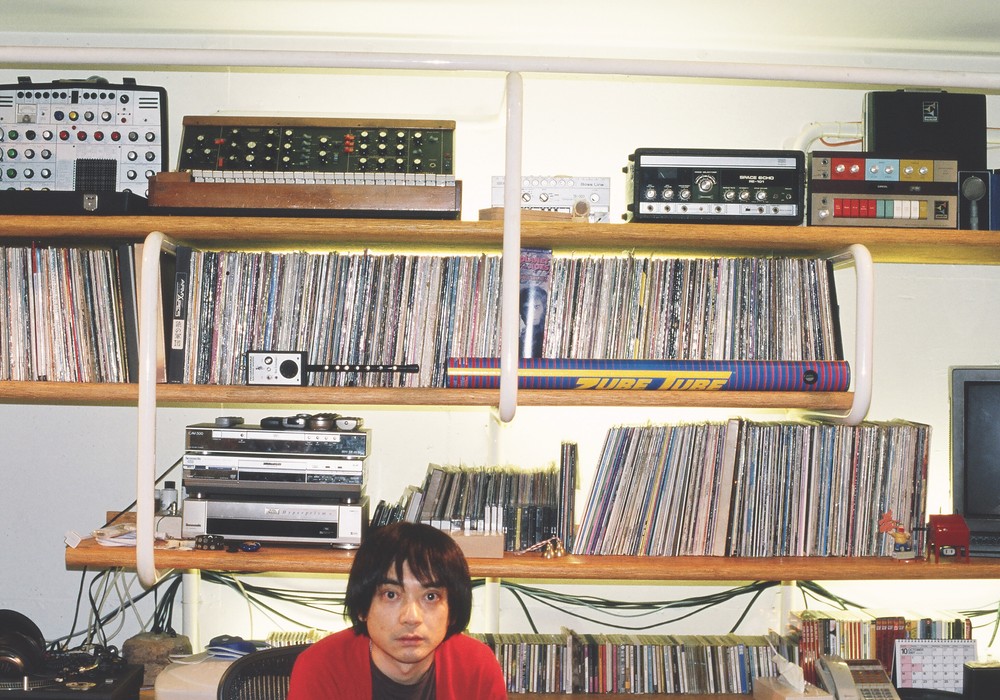

It's in Dan's living room. It started out in the basement but there's a nicer view from the living room. So we slowly started moving everything up. It consists of two small Neve consoles — little sidecars called Kelsos. They have a two band fixed EQ, two sends and that's it. Left and right stereo selectors so there's only hard panning. And that's what we mixed the record on. We got two of them daisy-chained together. Then a third Neve console, a Melbourne, we use to go to tape and a bunch of ribbon mics, a lot of Shure 57s and a couple Neumanns.

So during these past few years — you've been learning much about artists and their idiosyncrasies?

It's very psychological dealing with people and the setup to get a great performance. Just recently, on this Brian Blade record, we decided not to use headphones so the band would sit very close to each other. The best-sounding things were the rehearsals before the take — no headphones, huddled around each other, so we thought, 'Let's record it that way.' And you get a better tone out of the instrument because you're hearing the instrument instead of the boxed-in sound in your headphones and you're hearing the guys next to you instead of the mix, which won't always be right for everybody. You get a really beautiful sound that way.

I find people play more softly as well when separated and going through the headphones.

Right — especially with acoustic instruments, the player can't always get their instrument to speak as they do when they're sitting in their bedroom. And that follows the philosophy that the absolute most important thing in the studio is the sound before the microphone. The amount of talk that goes on about this kind of preamp, or recording on analog tape or whatever — if the guy is playing with a pick or not, it's going to change your sound far more drastically than any of those other variables.

I believe that 90% of someone's sound is in their hands, and the other 10% is the equipment — be it the guitar, pedal, amp or whatever.

Absolutely — Jimi Hendrix would have sounded great on anybody's guitar.

And keep striving for a sound, and getting the right mix until you feel it's done.

That's another thing — making decisions along the way. That's something that doesn't get done as much today because of the ability to keep every single thing. Sometimes out of limitations you get great results, which you clearly see in Hendrix's or The Beatles' work. And it's something we've found with our little studio — having two sends and fixed EQs — you have to make broad strokes. You have two effects — a lot of times we used only one effect — just a delay and you end up printing your effects. You get a kind of cohesiveness that you might not get if you have unlimited options. We were only working in 24 tracks, never had more than 24 — in fact, a lot were 16 or less. A couple of them were 6 tracks — the instrumentals. One of the instrumentals is mono — one track. Those kinds of limitations really help in focusing and giving your work a cohesiveness. Another philosophy that we follow in the studio is that of dedicating equipment — having one piece of gear do one job. Not using your console for your cue sends, and going to tape and listening back from tape. We only monitor on the main console, go to tape with different mic pres, out of another console if you have one, using another system again for cues. Therefore, you don't get locked into a certain mode and not having options available. You got all options available at all times. That's something that's very convenient.

You've been recording all the shows on this tour, obviously...

Yeah we've been recording them. Right onto DAT, just the soundboard mix. In fact, Jennifer Tipoulow films the shows on video and she gets a recording of the audio. What we do if we want to use it is blend the soundboard recording with her room recording...

And you'd sync it..

We'd just line it up in the computer. You get the punch of the soundboard and you get the ambience of the audio through the video camera recording.

And I remember something about Dan using a motorcycle helmet that had a microphone in it.

Yeah, the helmet microphone. We'd also use it for isolation. I took a SM 57 and removed the capsule and stuck it to the front of the helmet, wired the connector onto the back, that way the singer could be in the same room as the drummer. So Dan puts the helmet on, stands next to Brian, and gets a live vocal without any drum bleed. It's a vocal booth just for his head.

So would this mean he'd usually end up using what would normally be a scratch vocal as the take that gets used in printed take?

Yeah, a lot of times the main vocal is the live one. The helmet-microphone is a great tool.

I wanted to ask about the mastering of Shine. In the credits there is a thank you to Doug Sax, yet there is no solid traditional mastering credit going on.

Most of it was mastered by Doug Sax and Robert Hadley and some of it was done in-house. I guess the idea being that the guy doing your whole record in one day, he's gonna make some things sound better, some things not. There's no reason to expect that someone would get it all right in one go, never having heard it before. So some of the songs were better, some weren't so. We did them at home through an API 560, which were in a lunch box — they came out of Dan's API console from New Orleans and a Neve compressor and we just mastered it ourselves. Then just flew it in direct — you still have to put it in through a mastering computer at the end to get the right print for the duplication plant.

So what did you use? Did you try to minimize the path or...?

I would put it back to DAT and then bring it into the Mastering Lab and run it in direct with no processing. Because it's all done into computers these days and they do the spacing and do their prints to the format, which the CD manufacturers need to see.

So which formats did you mix to? Half inch and...

Some of it was mixed to half-inch, some to DAT.

Seems like middle-level studios are suffering these days a little — there's the ultra high-end and then the home situation, with people buying [Digi] 001 or 002 interfaces for their computers.

Well, I hope all those studios continue to thrive — there are a lot of great studios out there and they continue to get business. It's the rooms and all those great old 1970's class-A consoles — there's nothing like those. The great thing about that is being able to touch your equipment — having everything in a screen and doing data-entry all day is not the same as touching a fader and having moving parts.

It's one thing to record that way, but I find it uncomfortable when it comes to mixing.

Yeah, you can lose the spontaneity element.

Nothing beats having some crazy mix going on where you have to get more hands literally in there to get it done. Something very organic about it.

That's what we did on Dan's record. We had no automation and I would get up a blend and Dan would say from the other room, "That's great!"' and I wouldn't touch it, and he would come in, put his hands on the faders and my hands on the other faders and we'd put down a mix and that was it!

It feels more rewarding, when everyone had a part in it, even if there was someone around who just dropped by, and they even provided a touch to the mix.

Yeah, you get certain non-democratic results that way. Sometimes mixes are too democratic. Its like everything's in its place, everything is very visible. In fact, music isn't necessarily like that, some things are smokier in the background, depth of field comes into play and sometimes sitting around all day you lose that spontaneity, that magic that you can't necessarily put your finger on.