Mike Patton keeps busy — that’s for sure. Since his early days with rock band Faith No More (pioneering the rap-rock genre with their seminal hit “Epic”), through the schizophrenic compleit⁄ies of Mr. Bungle’s three albums, to his more recent work with bands Tomahawk and Fantomas (a supergroup including Melvins guitarist Buzz Osborne, Mr. Bungle bassist Trevor Dunn, and Slayer drummer Dave Lombardo), Mr. Patton has built a solid reputation as a musical maverick based on the unexpected volume and breadth of his catalog. In 1999, along with his manager Greg Werckman, Mike founded Ipecac Recordings, which, in addition to putting out Mike’s various projects, has since come to be known as a label specializing in musical misfits and very interesting albums which might not have found distribution otherwise. More recently, a non-singing role in director Steve Balderson’s 2004 film, Firecracker, has added to Mr. Patton’s resume of genre-breaking artistry.

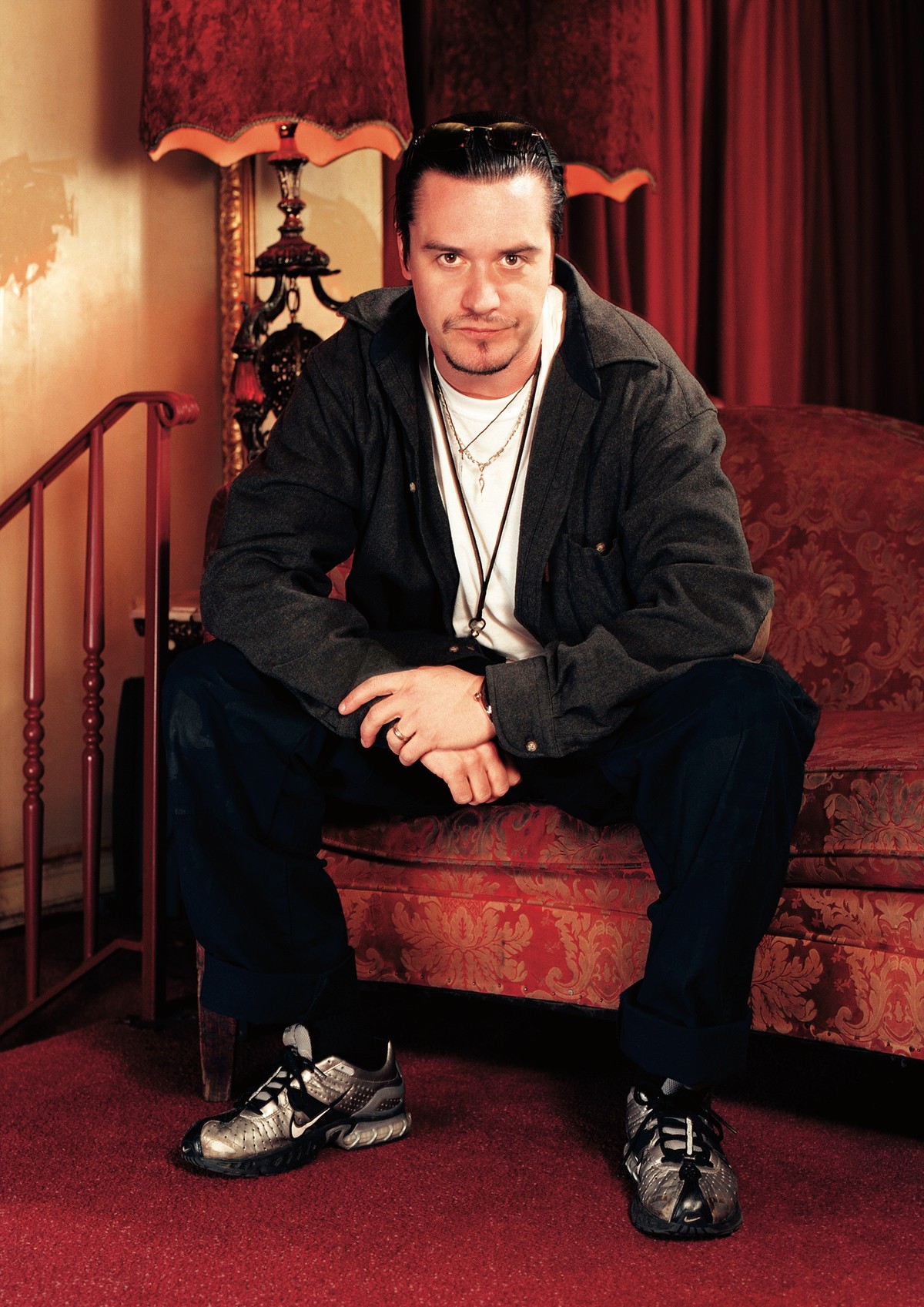

Photographer Brian T. Silak and I caught up with Mike backstage at New York City’s Irving Plaza several hours before Fantomas’ sold-out show at the same venue. Mike was kind enough to share with me his insights on creativity, the importance of believing in one’s artistic vision and the role of home recording technology in his recent projects.

As an artist, you seem to embody a deeply held philosophy of no compromise, of not being willing to subdue certain aspects of your personality or your music. You just put out what you feel and you are not so concerned about a commercial audience. How strongly do you actually feel that way?

So strongly that I don't even think about it anymore. There is no question. There is a right way and a wrong way and at this point I don't think that I could do it any other way. I'm "a lifer" and that's it.

Was there ever a time when the commercial side of things was more of a concern for you, or have you always felt so strongly about your vision of your music?

No, but there were times in my life when I was more impressionable. You know, the older you get and the longer you've been doing this stuff, the more convinced you are that you have to — because if you're not, no one else will. The older I've gotten, the more I've really relished what I'm doing and hated everything else.

How important to you — in music, life, everything — is originality, trying to say something new?

Well, it's pretty relative. Sometimes what sounds original to me could sound boring and contrived to someone else. I'm just making music that I feel compelled to make. It just happens that, for the most part, it doesn't fit nicely into a lot of categories that we've set up for ourselves — genres in music stores. There is no section where anything that I do would ever really fit. And I'm quite comfortable with that. I don't try to do it. It just happens naturally. You want people to enjoy it, but you're also not going to be jumping off the nearest bridge if they don't. Every project, the way I see it, is a different little universe. They all have their own little sets of rules and parameters, really. So, with a group like Fantomas, if I woke up one day and wanted to write some pop songs, I probably wouldn't bring them to that. There are certain projects that certain sounds are appropriate for. I like to compartmentalize.

It seems that you actually feel pretty comfortable putting yourself in uncomfortable situations.

Well, that's how you learn. That's the only way that I've been able to learn. That's how I learned to play music — by trying, by doing. By recording — by learning on the job, basically.

So you didn't go to music school? You didn't study voice?

No. I didn't really get a whole lot out of school. You learn by doing — by falling on your face at times, and by trial and error.

I read a Faith No More interview in which you and some of the other guys were saying, "It's not about thinking — It's about we get up here and we do this music and it rocks... it's not thinking." Recently it seems like you are actually putting music out there that is making people think more.

Hopefully. You know, it depends on the project. A band like this is obviously not background music. It's demanding. It demands your attention. There's a lot of detail in it and it's a pain in the ass to listen to. There's not a lot of "fun" listening.

How much of the instrumentation, the arrangements and the production of your current music is improvisation in the studio or live and how much of it is thought out in advance?

Well, with this band, it's all written. Very, very little improv at all. Basically, I record everything myself at home and make a crude version of what I want to hear, and then I have them learn it pretty much verbatim. They always make it better, which is what a band should do.

Where did your love of noise, and of shocking discords and level changes, come from?

Well, in this band, I think that our basic MO comes from just that. Very choppy start-stop contrasts. I grew up listening to a lot of death metal and hardcore stuff when I was a teenager. And that's something that I always loved about that music — and thought that it could be taken further. I think that if you sit down and dissect this music, it's a whole lot of clichés that a lot of us have heard before who know that music. It's just organized in a different way. I took the building blocks and I put them together a little bit differently.

I've noticed that your vocals have steadily moved from being up front and center in your mixes — like they were in the Faith No More and Mr. Bungle stuff — to being much more blended, as if you've specifically chosen to approach your voice as an instrument. Has that been a conscious transformation on your part?

No. The music dictates that. In a band like Fantomas, obviously we are not talking about "song form" here. We are talking about little tiny cells of music that move really quickly. I didn't feel that there was any need for words or other distracting information — so I knew immediately that I wanted the voice to be like another guitar. I wanted to be like a parrot, just imitating sound effects and whatnot. But by the same token, I just did a record with this guy Kaada [Kaada-Patton Romances] — and those vocals are straight up there. It just depends on what the music needs. In Fantomas, there's not a lot of space. There is no "front and center". That's just out of the question. So it needs to occupy a different role. And it's really fun for me to do that.

It's very cool that you approach your projects in terms of what the music dictates and not in terms of some preconceived notion of whom your audience is going to be.

That's all extraneous. I realized long ago that I can't control who the fuck listens to me. Or how many, or why. Or what if I looked a certain way or tried to sound a certain way? I couldn't do it if I tried. I gave up. You could go gray and have ulcers very quickly if you live that way.

How has your studio and production approach changed over the years as you've toured with different bands and worked on all of these different projects?

I do a lot more at home now. Because of technological reasons and my own ignorance, I used to always have to hire a studio and an engineer — buy the fucking tape, blah blah blah. I do a lot of it now on my own software, on the computer. I use Pro Tools. I also use Logic. It's amazing what you can get done on your own! I've cut out a whole stage, which is great. There are no more "demos". I don't have to make a demo for anything. The demos are the record. Why do it twice?

With Fantomas, you're giving the rest of the band all the parts. You've worked them out at home — and the guys are recreating them in studio on their specific instruments.

Well, now Fantomas is a band, so I feel like I'm writing for them. I give them rough sketches with fake drums and bad guitar. A lot of the stuff ends up making it. A lot of the stuff I resample and play along with Buzz. On the Delirium record [Fantomas' Delirium Cordia], most of the stuff I did at home, and had the guys overdub on that. Putting a studio in my pad was one of the best things I ever did. I can't believe I didn't do it sooner.

What made you finally do it, as opposed to not having done it before?

I guess I finally grew some balls. I really don't know. I live in this place where it's like two flats. I used to rent one out. And then I finally realized, what the fuck am I doing? I'm not some fucking landlord! So I made it a studio. It's real small. But up until that point I was doing it in this laundry room.

Not with the washers and driers going?!

Oh yeah — it was right next to the furnace — and I found out later that there was a carbon monoxide leak. A guy came and was replacing my furnace and he had this little tester. Beep beep beep. And he said, "You don't spend a lot of time down here, do you?" And there was the piano and I was like, "No, no." He goes, "Well you wouldn't really pass out, but the cumulative effect..." My wife immediately said, "No wonder you've been making that fucking music! You've been poisoning yourself down there!"

When you are recording at home do you use all the virtual stuff? Does your Pro Tools become a video game with all the virtual effects units and such or do actually have equipment, outboard gear?

Some, but I have stuff too. I like to mix it up. Well, there's some stuff that I've just gotten so comfortable with over the years. I have this old, shitty dbx — what is it, maybe a 163? Shit. Love it. Use it on vocals all the time — use it on everything.

It's interesting to learn that a large portion of the music on your recent albums has actually come from your home recordings.

It's kind of the way I've learned to do it. Having no real musical education, my canvas — the only way I can document the stuff — is by pressing record on whatever it may be. Ghetto blaster. I'm constantly leaving myself messages at home. In a way, I had to learn how to use "the studio" as an instrument.

I want to talk for a moment about your association with John Zorn. When and how did that happen, and how has it influenced your music and production style?

I guess I maybe met him in '90 or '91, and I asked him to work with Mr. Bungle. I had heard a bunch of his records and liked them. I approached him, and he was really into it. We kind of became friends, started off with a bang, and have been working together ever since. He'll be here tonight. I think that obviously I've learned a lot from his music, but he's a pretty amazing person and I've learned a lot personally from him as well. He's been like family.

Those currents were present in your music even before you met him, I think. You've gravitated towards each other because of what you both have in common.

We have a lot of common threads, for sure. And he was one of the people really urging me to start my own label. He had done so before and said, "It's gonna be a whole new world for you. This is going to be your thing — you gotta do it." And he was right. I've been incredibly fortunate to have a friend like that — who is also a peer and a mentor and everything else. I wouldn't be doing half the shit I'm doing if I wasn't close with him. I would be doing something — but I've taken some detours and I think that he really helped me make some good decisions.

In 1999, you founded Ipecac Recordings with your manager, Greg. How has Mike Patton "the label owner" made you look at yourself differently?

All of a sudden, it's like having a roof over your head. It's nice to not have to pimp your work to anybody. That's one thing that I really don't miss. And no one going, "Can you make it sound a little more like this?" No one can say shit. So it's really having complete control, owning your own music — and you don't have to sell it to someone. I'm really glad I did it.

Are you actively involved in choosing all of the acts that are on your label? Do you handpick them?

Yeah. That's kind of my "job". Everyone else does the "real work." We have two other people — my partner and one employee — and that's it. Keep the overhead low. We're able to structure deals that are totally, amazingly fair — the way it should be. It's not difficult at all. Having that going has really been amazing.

I look at some of the bands you've signed, and then you also have The Kids of Widney High [an album comprised of the results of a songwriting class held at a public special education high school in Los Angeles, Ipecac, 1999]. This really spans a huge spectrum of musical possibilities!

Kind of the way I knew it would have to be from the get-go. It's the way I listen to stuff. It's the way I write stuff. I'm glad that it's working and that people are interested in it. Because it could have very easily been a career suicide- type of move. I mean, most labels don't do that. They figure out a sound and stick with it. What I thought was, "Why bother competing with them? So many people are doing that. Why don't we try something else — and see if people can deal with it?"

Are there any words of wisdom that you'd like to impart to my readers?

Record your own shit. Don't worry about what some fucking engineer is going to tell you. Don't worry about the right way to do it. You can make incredible music on that [pointing to my digital pocket dictation recorder]. And you're the only one who is going to know how to record it right. Don't hire someone to tell you what to do. It won't work. If you need to be told what to do, then you don't know what you want. It sounds simple, knowing what you want — but sometimes it's the most difficult thing. And believing in it. And seeing it through. Some of my favorite shit that I've recorded was just done absolutely completely wrong because I didn't know what I was doing.

That's probably what made it so special.

I don't know. Can't tell you how many times I've gone back to some sort of microcassette recording and gone, 'I'm using that.' It's on the fucking CD! I did a whole record of just 4-track voice things in hotel rooms.

Was that your solo album, Adult Themes for Voice [released on Zorn's own Tzadik label]?

Yeah. That was kind of my last little love affair with the 4- track. I don't know. I just think doing it yourself is always the best place to start — that's for damn sure! But it might also be the best place to end.

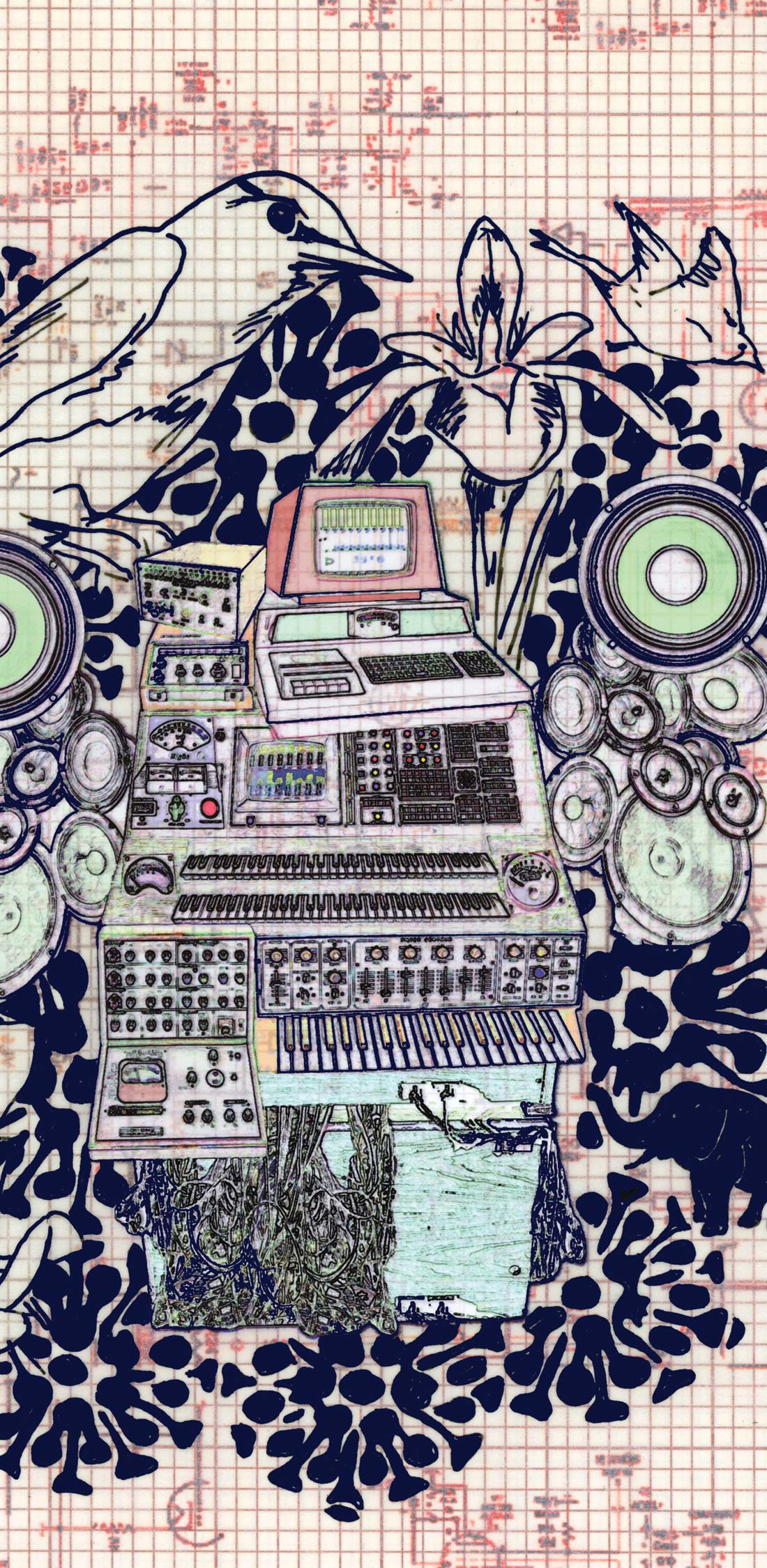

_display_horizontal.jpg)