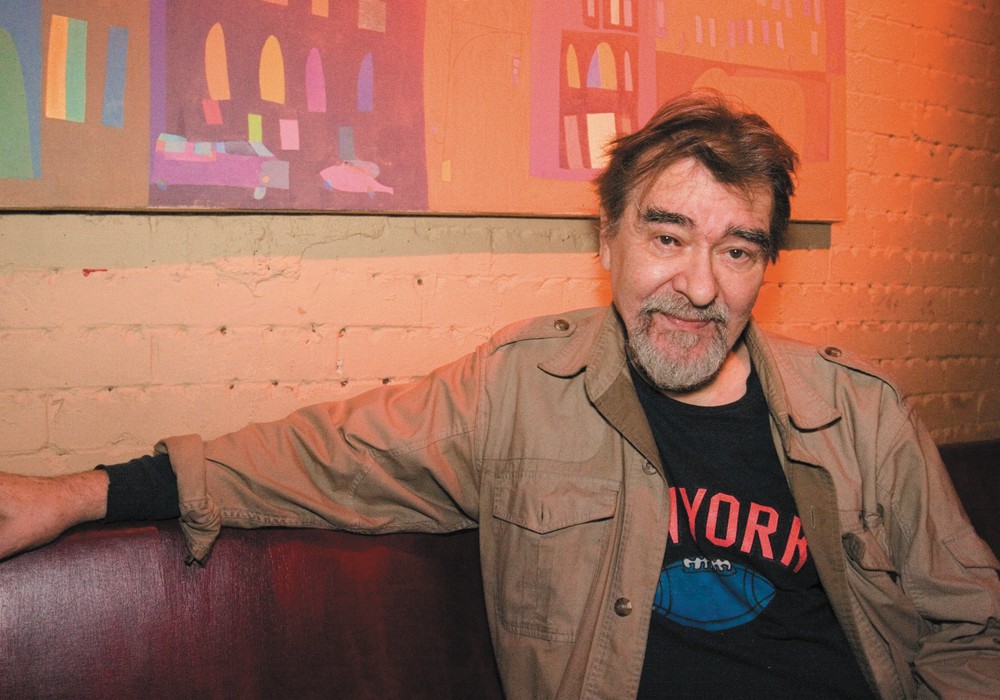

Classical recording engineers rarely get the same attention that their pop and rock counterparts do. While pioneers such as Robert Fine [Tape Op #90] (Mercury, Fine Sound), Kenneth Wilkinson (Decca), Lewis Layton (RCA) and Fred Plaut (Columbia) rarely get mentioned in trade magazines, they have created some of the most stellar recordings of our time, as well as developed techniques that influence to this day. Marc Aubort has been recording for more than half a century. From wire recorders onwards, he has used virtually every analog and digital format to capture classical music on location. Classical engineers still frequently refer to his recordings on Nonesuch during the '70s as a yardstick for their incredible, dynamic range and truth of timbre. After six Grammys and over a thousand recordings on Vox, Nonesuch, EMI, BMG, Philips Classical and other labels, Marc continues working today as he always did, relying primarily on a spaced pair of tube Schoeps mics. We spoke at Marc's Elite Recordings office, located in New York's Masonic Hall Building.

Can you talk a little about how you got into recording engineering? Did you start out as a musician or engineer?

Both actually, but at first I didn't combine the two. I lived in Switzerland at that time. I came to the U.S. when I was 28. I had built an amplifier that didn't work, so I went to the local hi-fi guru [Freddy Whettler] in Zurich to ask him what was wrong with it. He looked at it and said, well, you have to ground it here, you have to do this, you have to do that... Then it worked — we became friends and he became my boss. He was very much involved in recordings and building equipment. We started out on wire recorders, editing by knotting the wires together, then progressed to the Magnecorders — that was a mono machine. It was sent by a company in New York for us to record in Europe for them. The company was MMS [Music Masterpiece Society]. We called it Music Murder Society. [laughs] That was the reason everything started to roll, because my boss was so mad about what they were doing with equalizers in the States (basically boosting mid-range to sound better on cheap equipment). He didn't spare any words about that.

When was this?

1955. They wanted to fire him and put me in his place. I didn't want that — he was my mentor and friend. I called Vanguard here [in New York] because I knew their recordings. At first I wrote but I didn't get any answers. Then I called Seymour Solomon, who was the head of Vanguard. He told me, "Well, I'll be in Vienna. Come over and we'll see." That's how I became assistant producer and engineer at Vanguard. In '65 I left Vanguard and started Elite Recordings.

So you trained mostly with your mentor in Switzerland?

The technical part, yes, but I already had a musical background. He was a technical wizard — we complimented each on the musical side, overlapping on the technical side. That's also the way I worked when later, Joanna Nickrenz joined in '69. We both were producing and I was engineering. It slowly overlapped since she was doing all the editing, so I said if you're doing all the editing you might as well produce.

How have your recording techniques evolved over such a long career in classical work? How, for example, did you mic up the early Vanguard sessions?

Even before that, the idea was, to be as faithful to the score as possible and not try to gimmick things up. And that led to essentially two mic pickups for stereo and possibly some reinforcement. But keeping in mind that you have two ears, two microphones are what you need for stereo. In other words, not to flatten out the stage by having all sorts of microphones in the orchestra, bringing everything forward. The back of the orchestra is not meant to be heard up close.

In a recording, do you try to present an ideal audience perspective, say in the center of the 12th row?

To a certain extent, yes. But keeping in mind that a recording is a recording, and there are a couple of things that you have to take into consideration. You don't have visual contact with the artist on stage. But in essence I'm trying to get as good as possible a sound, say fourth or fifth row, about ten feet up, so that you have an overview of the orchestra.

Did you experiment with many stereo main pairs before settling on what you have now?

I have used the same microphones since 1960. And so far I have not found better ones.

The Schoeps 221s [with the 934 capsule]?

Yes. I have nine other Schoeps CM60s that I use for reinforcement, and they have essentially the same sound. Even in Europe, I was using Schoeps. I knew Schoeps personally in Karlsruhe, my boss was a friend of his, and ever since, I've been using the same mic. I've tried others, but for one reason or another I'd give up on them. There's another very famous microphone that we used on...