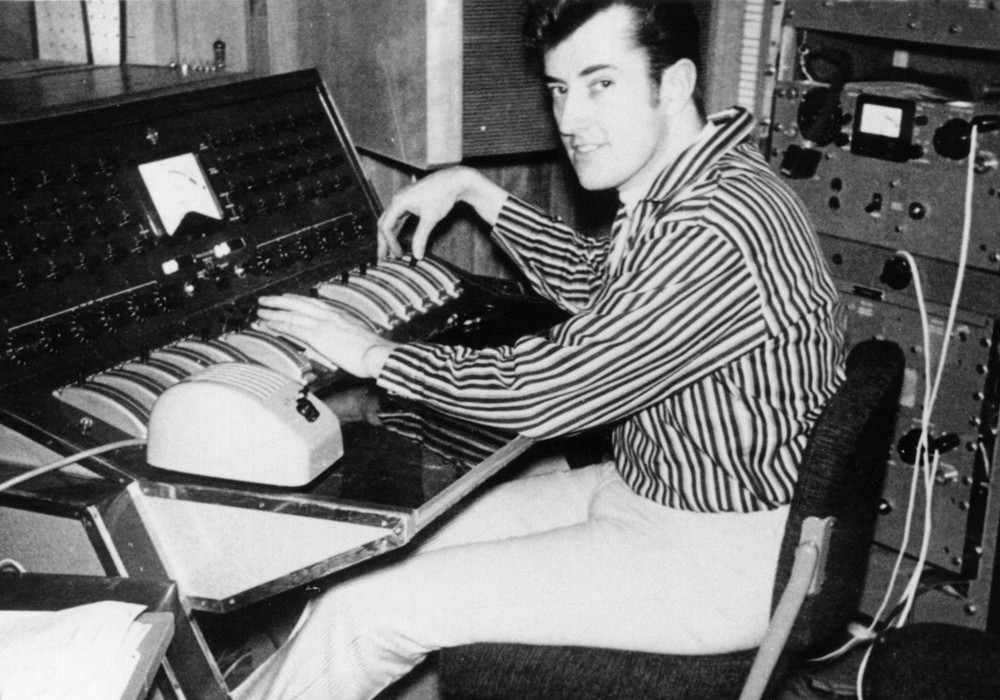

As I get to know Stephen, I realize that his internal mixing board is always on. His current project involves taking field recordings from various locations in Virginia and extracting alien soundscapes from territory I mistakenly consider so familiar. My ears are exercising as they search for the digitally-treated organic sounds that make up the compositions on his most recent solo release, Scratchy Monsters, Laughing Ghosts. His expertise also encompasses the understanding of sound's physical aspects, making him a sought-after man by visual artists, choreographers, filmmakers and musicians all over the world. Vitiello's musical collaborators span genres from electronic musicians Scanner and Andrew Deutsch to the classical sextet Eighth Blackbird. In 1999, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council awarded him a six-month World Views residency on the 91st floor of the World Trade Center where he used contact and photocell microphones to translate his multiple sensory experiences into audio format. Both humble and generous with his encyclopedic knowledge of sound, I am lucky to catch up with him in our hometown of Richmond, Virginia (where he is a professor at Virginia Commonwealth University) in between his travels to London, New York and Cologne to perform and install a site-specific piece, and accept the Nam June Paik Award respectively.

What equipment are you using for your Virginia field recordings ("Dogs in the Yard, Birds Overhead")?

I feel really fortunate to have been able to vastly upgrade my recording rig in the last year. In the past, I would go out into the field, including the Brazilian Amazon, with a small Sony DAT recorder and any affordable, handheld stereo mic. I'd also bring an assortment of contact microphones and small binaural mics. I had some success with a Crown SASS mic [PZM stereo]. At the moment, I am using a Sound Devices 722 hard disk recorder, a Schoeps CMXY stereo [condenser] mic and a Sennheiser MKH short shotgun microphone. I bring along a mic stand but also a pistol grip and short boom pole. The Sound Devices is an amazing machine. It has excellent preamps as well as a 40 GB hard drive. I generally record at 24 bit, 96 k. The Schoeps in particular captures high frequencies like nothing else I know of. The recordings I've been doing will end up in various forms, both as multi-channel installations as well as stereo tracks for an upcoming CD on the Portuguese label, SIRR. I don't have the ability to record in surround so I will often process stereo tracks with a very nice plug-in, ARL Sound Stage, that my friend Paul Geluso worked on. Some of the recordings remain fairly pristine; others are mangled and played with. I've been using Ableton Live for several years for mixing and processing, but recently I am trying to stay a bit outside the box, using a small Doepfer analog suitcase-style synth as a processor. It's all been a bit of a learning curve — recording with something as sensitive as the Schoeps means either leaving the mic to record alone and/or learning to do as little breathing, moving or twitching as possible. When I first got it, I thought there was some problem with an occasional cracking noise that I heard through the headphones. I eventually realized it was the sound of my wrist! One of the most amazing sites I've been recording in recently is a newly discovered forest about two hours south of Richmond. The forest is incredibly quiet. Occasionally an owl will call out in the late afternoon. I've also heard the inevitable boom and splash of trees falling in the distance.

How have your techniques changed from when you first started recording outside of the home/studio environment?

A lot of my original recordings were in New York. I did recordings inside the World Trade Center using contact microphones on the windows. I did recordings in Grand Central Station (an amazing acoustic chamber) — subways, streets, shipyards. In all of those cases, the equipment was small and there was enough noise around that I could just use the mic as an extension of my arms, hands as well as head with the binaurals. With this new setup, and often in much quieter environments, I've found that I have to become invisible and silent. I do all that I can to allow the microphone to capture the environmental sounds as they would exist if I weren't there. I found out early on that this too is not always entirely possible. I was recording in a marsh inside of James River State Park. I'd been there several times, falling in love with the balance of insects, birds, crickets and bullfrogs. I had my microphone on a boom pole, stuck through some thicket. I couldn't exactly see what the microphone was recording. Suddenly I heard a whoosh and a high frequency breathy sound that would speed up and stop. I thought it might be an owl, maybe a jabberwocky. I posted the sound to the sound recordists list serve and was told by two members of this group that it was the warning call of the young white tailed deer. I had been spotted and she was sending out the signal for all deer to stay away! I've learned a great deal from following the sound recordists group. One difference of what I do compared to many on the list is...