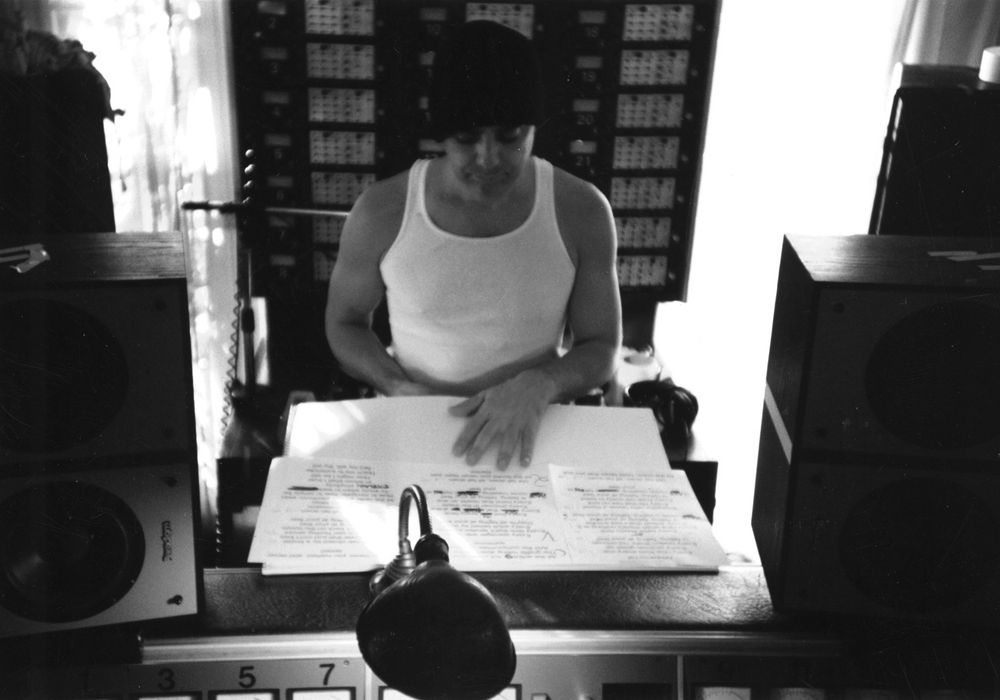

Kevin Killen has helped create what many consider some of the most important records of our time. Peter Gabriel's So and U2's The Unforgettable Fire crown an impressive discography that includes Tori Amos, Elvis Costello, Prince, Laurie Anderson, Stevie Nicks, Brian Ferry and Patti Smith. Always forward thinking, Kevin is a founding member of an online record- making community called eSessions (see issue #62, Gina Fant-Saez), has fully embraced mixing in the box (without an analog 2-bus chain) and continues to evolve his record-making approach as economies, technology and culture rapidly change. Given his track record it's difficult to grasp him telling me that he still wakes up some days and wonders if he's still got a career. Yet this remark is a good example of how Kevin's warm and humble personality shines through the glitter of a hit-studded discography to open up a candid conversation about making records as well as his career. We got together at Mavericks Studio in NYC and talked about everything from Ireland's early punk scene, to the technical perils of making So, to Kevin's first leap into producing and Kevin's proclivity for mixing in the box.

Tell me about those early days in Ireland in the punk scene. Was it the late '70s roughly that you started engineering?

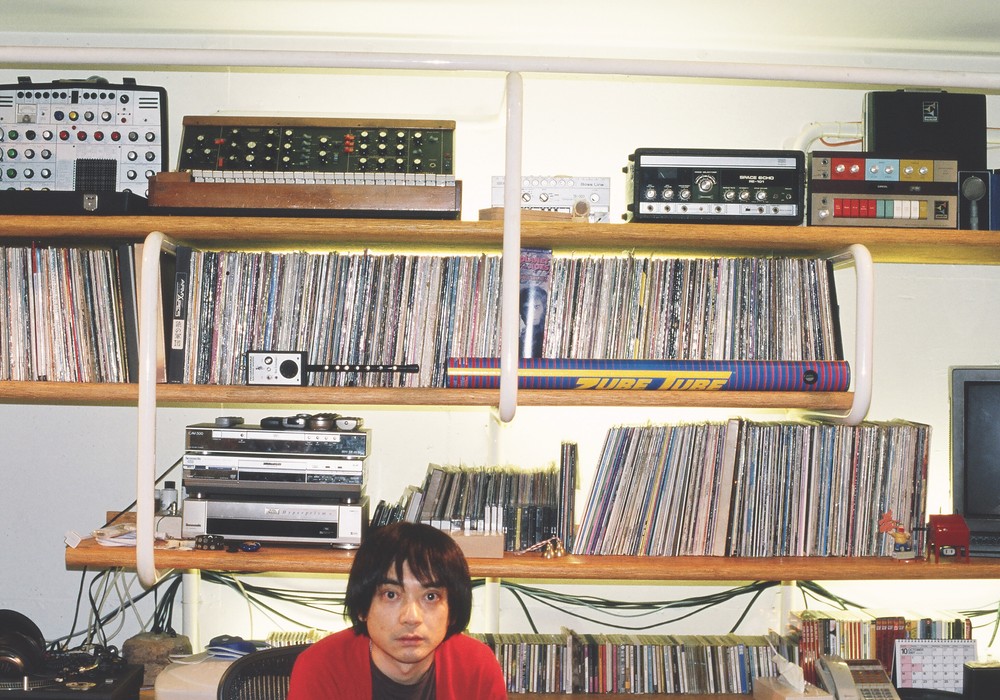

The late '70s and early '80s. The first studio I worked at was called Lombard Sound. It's still in existence, though it's changed its name to Westland Sound. It was a small 24-track analog studio. There were two principal owners. One of the owners ran an ad agency, so typically we got jingles from about eight in the morning 'til lunchtime. We always had an album project, be it traditional Irish music or some other album. Back then management was very keen to have the junior assistants, of whom I was one, bring in outside projects. The punk and new wave scene were really proliferating there. Everyone was in a band. Everyone wanted to make a demo tape with the hope of getting signed to a major label in the UK. The impetus for a lot of my training was [wanting to go] from that hectic jingle session to having a bit more time and leeway in a regular session. I did frenetic eight hour, do-as-much-as- you-can sessions because the studio would allow the client to come in for a couple-hundred dollars for the night. You got one of the junior engineers, which was either myself or maybe Gerry Leonard, who is David Bowie's MD [musical director] and is MD'ing with Rufus Wainwright now. One of the owner's sons was the other junior engineer. We also had a couple of people who would come in and freelance. Management encouraged us to go out and find projects and they would assign us to projects based on either recommendations or whether you happened to be in the studio that day. It was a really great training ground because I was allowed to make mistakes and from those I grew. The house engineers, Philip Begley and Fred Meijer, would critique our work — it was great because they could put up the multitrack and listen to how we recorded basic things and they'd ask questions and then make suggestions. It was really a hands-on experience.

That sounds like a great education

It was a great education — I learned a lot. Within five to six months of joining I was engineering my first full- time session on my own with no assistance. I had to set up the room, do the tape alignment on the machines, set up all the mics, get all the balances, do the headphones, make the tea [laughs] — which I was doing all at the same time. I completed the tape logs, the sessions data, made the copies afterwards, leadered the tapes.

Sounds like a lot of work.

It was a lot of work but there's no way I would have been able to propel my career as quickly as I did without that experience. It gave me such a good grounding.

In these late night sessions did you record, mix and finish that night; or were they coming back to mix? How fast was it?

Some of them were a wrap in one evening — typically two or three songs. And it could also be somewhat delusional, meaning that the bands were thinking, "We play this as a three minute song, so how long could it take to record?" They were thinking, "With eight hours, gosh, we could record a whole album!"

Fast records!

They were not taking into account the whole set up and getting everyone comfortable in that environment. Some of them literally ran the gamut of completion from beginning to finish, as many tunes as you could do. Some of them said, "We're going to try and get drums, bass and guitars. Then we're going to come back another evening and do vocals and additional overdubs. Then we'll set aside a separate time to mix." Initially a lot of bands started out in the first mind- frame and then started moving gradually towards slightly elongated projects. But typically they'd be done in two to four nights, so I'd have maybe thirty- two to forty hours maximum to get the whole project done. We sometime had to hurry because these bands were...