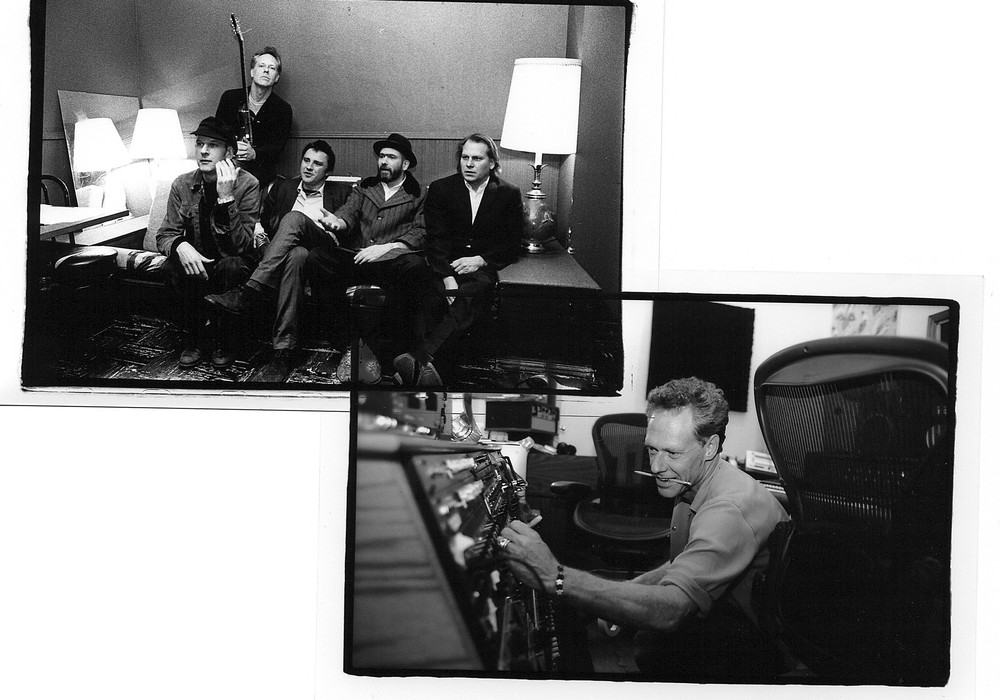

Sometimes you get to meet people who were your heroes back when you were a teen. The first time a 16-year-old me heard Gang of Four, a "post punk" band from Leeds, England, the directness of the vocals, the taut rhythm section and slashing, stuttering guitars of Andy Gill made a huge and lasting impression. To be sitting in Andy Gill's personal recording studio (in the Beauchamp Building, London) nearly 30 years later and finding him to be an engaging and interesting person was a treat. Not only is Andy an inspiring guitarist, but along the way he became a producer — not only with Gang of Four, but also on albums with The Jesus Lizard, The Futureheads, Michael Hutchence, Killing Joke, Red Hot Chili Peppers, We Are Standard, Asyl, Detlef Zoo, The Stranglers and The Young Knives.

You started out co-producing with Gang of Four.

Yeah, that's when I was learning how to, on Entertainment! Then, on [second album] Solid Gold, I think we got a bit more sophisticated.

When you listen to [third album] Songs of the Free it's got more of a studio- savvy feel to it as well. You're hearing synthesizers, layered backing vocals and such. Outside of that, who was the first artist to call you to produce?

I did a little bit with bands like Delta 5.

Most people wouldn't remember that. [laughter]

Yeah, I know. You know who they are though, right? I was talking to an American woman the other night who said that she danced at Studio 54 to "Mind Your Own Business" by Delta 5, which was a bit of a club hit. So stuff like that I was a bit involved in. But the first big one was The Red Hot Chili Peppers on Capitol [first, self-titled LP, 1984].

And they searched you out based on Gang of Four?

Flea and Anthony [Kiedis, vocalist] told me the reason they formed was because Gang of Four was their all- time favorite band. That's what they wanted to do. So, obviously they wanted someone from the band. I was the one who was more production-inclined.

I think I remember hearing there was a bit of a rough time on that.

We had our good days and our bad days. I think the drug thing didn't help the situation. A lot of massive tension between Flea and guitarist Jack Sherman. I think they thought, as their sort of hero I suppose, I'd just hang out and befriend them. Somehow the music would come — we'd lay it down and it would be great. Like I wasn't going to get involved with, "You need to do this. Why don't we do the bass and drums first? This is a drum machine. We're going to use it to keep time for us."

Maybe a little more "hands on" than they were expecting?

Exactly. "We're gonna put your voice through a compressor, Anthony." "Compressor? But I want it bigger, not smaller!" I made him go and get some singing lessons. [laughter]

Where were you working on that?

Eldorado Recording Studios, in L.A.

Did you learn something from that experience? Such as mapping out "how we're gonna work together"?

Yeah. I learned a lot. Don't ever fight about it. Don't ever argue about something. There's always another way to skin a cat. Don't make one issue the be all and end all. You can go around it.

Like the old "just try it" and it will succeed or fail based on its own merits.

Yeah. With those band situations you want to say, "Let's just try this." "No. I don't want to try it. I don't like the idea." Not the right response! Sometimes, it's too many irons in the fire. I mean the drum machine thing was quite funny. At one point, Anthony grabbed one end of the drum machine and I grabbed the other. Anthony's saying, "Man, this thing has no fucking soul!" "Of course it's got no soul!" "Yeah, but it's like 1984!" And he was trying to grab it so he could smash it. In the end, we compromised with a click coming off it and Cliff Martinez, the drummer, would listen to the click and tap it out, which would make it "human," and then we worked with that click that he made. [laughter] Whatever works, you know! They felt better about it because there had been an intermediary.

Did you feel like you could have just used the drum machine click?

Yeah. But I feel like that about a lot of things I do.

Were you able to go and negotiate how you'd be working or discuss it first with the artist for projects after that?

Yeah, I think so. You talk it through. Everything's a lot easier after that! Basically you work with the band and talk through how they see it and how you could go about it — whether you're all gonna play it together or one at a time. A lot of it has to do with the songs. A lot of producers don't want to get too involved with arrangements and the function of bits. That type of conversation is like being in a band. You play your part and people comment. I think you pretty much work out straight away what's appropriate or not. I produced Killing Joke [their second self-titled album, 2003], but it wasn't until we recorded the first track that I discovered they didn't have any other songs. I thought we were coming in here to record an album, as they used to be called, and they lied to me and only had one song! "Andy, why don't you program a beat and I'll just do some bass."

That record too — all the drums were done to a loop or drum machine sequencer?

Yeah! I'll be totally honest. I'd do a rhythm, tapping it out, and then Jaz [Coleman, singer] would come in and say, "Make it sound more like 60 bpm faster please." It turned into something else. At some point it was Arabic punk. You start to say, "Not easy." Then suddenly you're at 150. When we first started, if I complained and said, "Jaz, it's completely different now." And he'd say, "Right. 10 bpm faster just to punish you!" [laugher]

So, did you stop saying anything at that point?

Yeah! But then, some pretty interesting things started happening. The beat sounded like nothing else. You start thinking it sounds like some kind of insane Middle Eastern music on sulfate. It was exactly the right thing for the backdrop — he had something in his mind. Dave Grohl then did all the drums in the end — after everything else had been tracked.

So, I imagine that would have to be in Pro Tools then?

It doesn't have to be, but it was. That was such a great thing, recording the drums in L.A. with Dave Grohl, because he is the best drummer I've ever worked with. It's amazing. One thing that I very often do, is after we've got drum takes in Pro Tools or Logic or whatever, I'll say, "Play loads of fills. Go insane. Just play fill after fill after fill all through the songs. Just ignore the structure and put fills wherever you want. And maybe do that a couple of times." That was really fun! He was just ridiculously showing off. A lot of drummers will go into a fill and aren't sure where it's going. They'll slow down a little bit and then it comes back in well off the beat. Or the opposite, speed up and come in way too early. But everything he did was absolutely rhythmically perfect. It was just ridiculous — starting on toms with sixteenth notes and ending in triplets on the snare. It was good!

Wow! So, you did initial tracking at your studio here?

We did everything here and then we went to Grand Master Studios in L.A. Great sound in there. He did everything. The first thing I said was, "What do you think about maybe hitting the cymbals separately? And maybe even the high-hat separately?" And I'm imagining, "No way." I had been out there two weeks before with the drummer from System of a Down [John Dolmayan]. He wanted to do it and I went out there, walked in and my heart sank because there was this massive kit that went for miles! Fourteen toms, little bells and gongs. I thought, "Oh, fuck. This isn't going to work." And it didn't. We got some recordings and I was trying to work with him. But he was going, "You know how my band sounds? I want to make it more like that." He was trying to change it and put his stamp on it. It didn't work out. With Dave Grohl I was kind of worried about a repeat performance of that sort of thing. But he was like, "How about leaving out cymbals and just doing basic stuff?" And I was like, "Sure! That's what I was going to do anyways."

You had him go in and add separate high-hat as an overdub?

Yeah. I can't remember what he started with, whether it was kick or snare, kick and snare at the same time and high- hat as an overdub. The toms were in there. Then we did the drum fill session, with everything playing at the same time. It worked perfectly. You can't spot the seams.

When you do something like that, do you come back to your studio and start rearranging?

We mixed it back here. You pretty much have it all done. He was staying very close to the parts. He loved the programmed stuff. He actually said to me, "I'm not just doing this because I love Killing Joke. I'm also doing this because these are really interesting drum parts."

Is it interesting going from something like that, where you're basically co- writing and then your next project might be a band?

Yeah, exactly. The Futureheads was my next project. You don't want any improve on the songs. They want suggestions and they want to know, "How do we best get that? How do we go about doing this?" But they don't want me telling them how to change something.

Did you make suggestions with them?

A couple of times.

Did they follow through or did suggestions just get brushed off?

A little bit brushed off. They did this cover of the Kate Bush song, "Hounds of Love". They're fantastic backing vocals. Just the guys doing the "ohhs". Each one's got a different note — like a barbershop quartet. I think their version is better than Kate Bush's — It sounds pretty damn good. I was trying to encourage them. They loved that. It really kind of grooved, especially on their own tracks — they were kind of stop/start-y, which is fine. I just wanted to encourage them to do more stuff like they were doing on "Hounds of Love".

Keeping with the groove?

Yeah. If you've got something good, keep it for more than ten seconds. That doesn't necessarily mean it's disco! They do that more nowadays. Some bands just need a bit of time to get used to a concept.

Do you find yourself asking artists, "What are you trying to say with this song?"

Quite often I literally don't know! I'm kind of like, "Give me a bit of a steer here." I did The Young Knives quite recently. I loved working with them. Very strong lyrics — you don't need to ask what they're about. You hear it. One song will be about somebody living at the seashore and losing her child at sea. And it's not a 17th century folk song — it's a post-punk thing. Another song's like a point of view from a student at university. There's a university here called Loughborough, quite well known for sports, and the song is called "Loughborough Suicide" — very dark humor. Not all are exclusively about death. One is about travel — very melancholy — or how shitty it is to work in an office, which is their background. You don't need to ask. The poetry is amazing — it really strikes you. And the Spanish guys with the English lyrics — I could make a guess, but I sometimes really don't know what they're going on about. Once he explained to me that the song was basically about trying to get another woman into bed with him and his partner. I would never have known from looking at the lyrics.

You obviously see your job as different in different scenarios.

I think that's something that very much changes. There's a French band called Asyl and they knew exactly what they wanted to do, the sound they were going for. It's simpler and I quite like that. You're just trying to get a great sound and get it big and pumping. Or Detlef Zoo. Every single thing they put out is a big hit in Latvia. Latvia's a small country. We were doing it here and I said, "Guys, this sounds fantastic. It's great. But there's no chorus." Or all of it sounded like a chorus and then there was no verse. There were no changes. He's a fantastic singer, really great voice. They'd have a chord sequence with his voice on it and it would be great, but it doesn't go anywhere. "Uh, Andy we thought maybe you could come up with something!" [laughter] "Oh, I see!" So, we'd sit around and write the rest of the song.

At this point, you've heard a rough version or first take?

We're sitting around in here going through everything. Really strong, strong base of ideas. Vocal melody and series of chords. But where does it go from there? There's a lot of lyric writing on that one as well.

Are they singing in English?

We did a lot of the tracks in both Latvian and English. There's the Latvian version and the English version of the album. Latvian is a strange language.

So, was it released in the UK in English and released in Latvian in Latvia?

Although it's number one on EMI Latvia, no one's put out a version over here, yet. I've just finished this Spanish band called We Are Standard, from Bilbao. They don't like to be called "Spanish" — they prefer to be called Basque. Everything has to be in English — they won't touch Spanish. I talked to the A&R man and said, "Surely if you do a Spanish version it's going to go down well in Spain?" "It doesn't work like that. Nobody cares if it's in English or Spanish."

I worked with a Swiss artist who did her album in English. One of the things that came out was she'd have odd language choices, word placement or pronunciations.

Oh, I've been there so many times! "How do you want to come across? Do you want to come across as someone [for whom] English might be his or her first language? Or do you want to come across as someone trying to sing in English?" "Oh, I want to come across as if it is my first language." "Okay, well we've got some work to do."

Have you had anybody that's said, "No. I like to keep it kind of naïve sounding."

No, but I'd love it if somebody would say that! [laughter] "I want to sound like a foreigner!" We Are Standard very much wanted it to sound not Spanish. They wanted it to work for an American audience. I had to correct a lot of the lyrical things, a lot of weird grammar. "No one would say it like that."

You've gotten so many jobs with people from other countries. How are the referrals coming at this point?

I'm not really sure. Some of them are Gang of Four freaks that think they want a bit of that sensibility. I think some them are interested that I have wide catalog from Michael Hutchence to Jesus Lizard to The Stranglers. It's quite odd.

Even in Gang of Four there are things that are sequencer-based and tracks that feel live off the floor. Jesus Lizard is a great example. What are you gonna do with that group? [laughter]

That's right. I was a bit obsessive about getting it really tight.

I know you worked really hard with David Yow on the vocals.

He was really surprised! "I'm quite enjoying this, Andy. I'm not used to it."

Were you asking him about lyrics and melody?

Lyrics, melody. Basically, [previous recordist] Steve Albini [Tape Op #87] was like, "You've got five minutes. Get in there and shout."

Steve's into a "documentary" approach. He does that really well.

He does. I think that's exactly how it happened. It was done with tape. I'm glad we did it they way we did it, but I was doing endless drop-ins. The drummer [Jim Kimball] was having a bit of a crisis over it. He was driving me crazy. I think when people get worried about stuff like that, maybe they're not that experienced. It becomes too detailed. "Why do have this microscope trained on me?"

What's your answer?

"I'm trying to make a really fantastic sounding record."

It seems like a lot of your production has to do with groove and tightness. Is that what lead you to sequencing?

I think so, yeah.

So you know precisely what your ideas will be?

On the album that Gang of Four did at the top of the '90s, called Mall, there's quite a lot of sequencer on that, but it's also got a lot of drums. There's something about a sequencer all on its own that's unsatisfactory.

With Michael Hutchence it seems part of the process was to build sequences, place some guitar on them, sing on them and then go play some other things.

Yeah, it was. Once that was all done, take it in the studio and bang on real drums.

Did you have to finish that record after his passing?

Yeah. That was very, very strange.

How soon did that happen?

Ages. When Michael died it was a very complicated situation with his estate, and his record was a part of that estate. It didn't belong to a record company. He was gonna make the record as he wanted it, get it exactly right, then hand it over. So, it sat on the shelf for about a year and a half. Then people were haggling about things. You can imagine. Richard Branson [Virgin, V2], when he discovered it was available said, "Let me pick this one up." One of my favorite tracks on the record is "Slide Away". Have you heard it? The one with Bono on it?

Oh, no. I've heard little snippets of it on your website. It sounds more layered, textured and personal than INXS.

Very personal. Very atmospheric. Very groove-oriented. I'm not a crazy fan of INXS, but I always thought he was a stunning singer. He was a stunning rock 'n' roll front man.

So "Slide Away" was a Bono duet?

Yeah. What happened was, when V2 got on board, they said, "Play me absolutely everything you've got." So I did — even stuff that was unfinished. "Slide Away" was one of those unfinished ones. Just great groove and guitar riffs. The vocals were not finished. We had a couple of ADAT tapes. But I played it to V2 and they said, "Oh! This track has got to be on there!" I said, "It can't be. It's not finished. The lyrics aren't finished and the vocals aren't there." "Oh, but it sounds so great." "The only thing I can think of is if Bono will sing some of it." So, I called up Bono and told him what I had said. And he was like, "Hmmm. Okay." Bono said, "Why don't you send me everything, and I'll pick which one I want to work on." I said, "Well, that's not the point." He said, "Nope. Just send me everything." So, I sent it all off to him. At this point, I'm not particularly hopeful. But, he comes back and says, "I love that track 'Slide Away'." I said, "Ah, yes!" [laughter] Results! For Michael's vocal part I went through all the ADAT tapes and got it all into Pro Tools. I was taking bits from there. I put together the first verse and we had the chorus. Basically the arrangement went — this first verse that I had put together, chorus, then the Bono section, then the chorus.

If this project had been thrown in your lap and you hadn't even been collaborating as a writer with him that would have been a pretty odd liberty to take. Did it feel more comfortable since you had been collaborating?

I felt totally right about it. I've always made it clear how it was done.

You were already hired to produce and write with him anyway.

Right. I think this record was 93 percent done when Michael died. Bono and me were good mates of Michael's — it's a good chance to say goodbye. Bono turned up with some vocal ideas and bits that he'd written and I'd written loads of words. We used bits of each other's stuff.

What kind of digital program are you using for recording?

Almost exclusively Logic, which has been a pig ever since we went to OSX, which has only been a year ago. It's had a lot of problems.

It's pretty interesting considering that Apple owns Logic.

Illogic. [laughter] The piggybacking of Logic onto the Pro Tools hardware seems to be the whole area that has not been well worked out. It's only a couple of months ago that the Intel Macs supported both Logic and Pro Tools. And we are told that they'll successfully work together in a stable way. That's what I'm going for now.

It's more of a hardware/interface issue?

Yeah. It crashes and weird things happen. When you get really quick on one system, it always feels really clunky going to something else. My first use of music and computers was having an Atari computer, which had a MIDI output on it. How clever is that? And then, the first Akai sampler that came out. That was it. Then, of course, you had the nightmare of making it sync up to tape. So, that's where I came from with music and computers.

I don't even see a tape deck in the studio here.

No. I did have a 2-inch machine. All the wiring is here for it. There was a 1/2-inch machine. Obviously there are those people who swear they can't live without the effect of tape compression and whatever it does to the transients. But I sort of figure I've got all this classic outboard and desk. I think it's a good combination of new tech and old tech.

If you're tracking in the digital realm you're going to use this Neve console for the mixing process and mix a few tracks back in, I assume? Do you do stem mixing at all?

I do, yeah.

So, you're combining those later in the box?

Whenever we do a mix, it's all coming out to the console. A few things are combined in the computer, but it's mostly individual outputs. We put the mix down and then we put the individual parts in. You put down all the stems because you don't really want to go back to the whole mix to do them.

So you get that flexibility if you get that call at 1 a.m. the day before mastering?

Yeah, exactly. A lot of people I know are mixing entirely

inside the computer these days.

Have you tried it?

I've never done it. The only thing I have done is when there's been some sort of recall — I've combined those stems without leaving the computer. That works fine. If you extend that argument logically, you can do the whole mix inside [the computer]. Something still feels wrong with that to me, but lots of people I know do it.

You've been busy lately?

Yeah, we've got new Gang of Four stuff. I could play you some, if you'd like.

Sure! Are these rough mixes at this point?

No. Finished mixes. I think I've got two or three weeks here where I can push this Gang of Four thing further forward.

We listen to Gang of Four's new single, "Second Life".

I want to work on Gang of Four. We had a meeting this morning. "Where's it going? A collection of ten songs, or is it going to be something else?"

Has doing the Gang of Four reunion in 2004 given you a different kind of profile and brought more production work in?

Not really. I mean from 2003 to 2005 I was really working hard. Doing stuff like the Killing Joke album and The Futureheads first album. In 2005 I didn't stop for a second. That mostly involved squeezing in Gang of Four shows and doing the Return the Gift album.

I thought that was an interesting idea, to cover your back catalog on Return the Gift. On the original albums were you working with outside producers and engineers?

When we did Entertainment! we didn't have a producer — we produced it ourselves. We didn't have a clue what we were doing. You can sort of hear the sound that you're going for, but you don't know how you do it. It was like we were getting to the edge of our ability just trying to describe a reverb.

Where were you working at when you tracked Entertainment!?

Workhouse Studios. Good name! It used to belong to Manfred Mann. It was down Old Kent Road, which is like a poor, seedy part on the main road out of South London. It was a carpet-lined room, literally.

Sounds like it on that record.

Yeah, that's right. We had the house engineer [Rick Walton] and that was it.

Did you guys call the shots on where you wanted to go? Did the label say anything?

Yeah. Me and Jon [King, vocalist], we would sort of argue about how it was supposed to sound. We'd be like, "Let's put a bit of reverb on that." Of course, we didn't have any reverb because they hadn't invented it! [laughter]

It's a spring, or piece of tape.

We had a "lively" effect — a speaker hanging over a toilet with a microphone in the room. That was it. "How much toilet do you want on this?" And then we'd argue about it. "No! That's too commercial!"

Going back to re-record stuff from that era, what did you hear that you wanted to change?

Well, it's like you said. It sounds like that carpet-lined room. I'm sort of conflicted about this — in a way I find the sound charming. You know? The fact that anybody with any expertise has clearly been banned from the room. [laughter] But then I sort of think if you listen to that record you wouldn't have a clue what we sounded like live, because it's a completely different thing — the kind of physical assault that you get from the live thing.

But in a way it's like a funk record, like James Brown's '70s era. Tight, dry, but it keeps things focused in your face. When I first heard your albums we thought they sounded like a funk record played by a punk band.

Well, you're absolutely on it. I remember when we did Return the Gift, getting a little bit of flack from some people saying it was sacrilege. You know, "What do you think you're doing?"

But if someone else had done it, it would be a tribute!

Well, we've got the original and you can listen to that one if you want! We've got this version, which has a bit more muscle to the drums. It's all about making the drums sound a bit more like they do live — powerful. It's obviously got a lot to do with compression. We record in there [points to live room] and then we sometimes put speakers out there [points to open stairwell area]. We can get a roomy kind of thing out there. And Jon's voice, I think, is so much better than it was then. It just sounds amazing now, I think. His voice has changed so much.

What do you think attributes to that? Just having sung for so many years now? Growing as a person?

If you compare the two, I think it's singing and experience. His voice is a lot richer. You can definitely hear that. I think his voice just sounds brilliant.

How quick was that record to make?

It wasn't that quick because we got excited about the way things were sounding in rehearsal and that was the impetus for it. It was like, "Let's do some recordings. Let's do some of our songs." But, we weren't rehearsed well enough to do it as a band, all in one go. I really like it — I think it's a good sounding record. It's pretty different from the first recording.

When did you put this studio space together?

About ten years ago.

Did you find it a necessity to have a space to work in, to even do pre-production or writing?

Yeah, the space I was in before called for improvising. I had a DDA desk, which is about half the size of this, just in the front room.

Of the place you were living?

Yeah.

Would that have been invasive?

Yeah. The girlfriend wasn't always happy about it. [laughter] She describes lying in bed fucked up with the flu, and waking up to find a musician sitting on the end of the bed. After that, she said, "You know, I really think we need to find someplace else." This place was just a big shell — nothing in it. I was looking for ages and ages.

Were you able to buy the place?

Yeah, it was a lot money and a lot of grief to get it fitted out. I live above the shop.

I'll bet no one's going and sitting on the bed here.

No! It hasn't happened yet. [laughter]

Even if you're tracking in a larger studio you probably end up back here to do overdubs and mixes.

Yeah. A lot of stuff I do here. But even if part of it's been done elsewhere it will probably involve coming back here.

I don't imagine you're trying to run it like a typical studio and get other people in here engineering, producing and doing other things.

There are other commercial studios out there — I'm not trying to compete with them.

www.gillmusic.com, www.gangoffour.co.uk