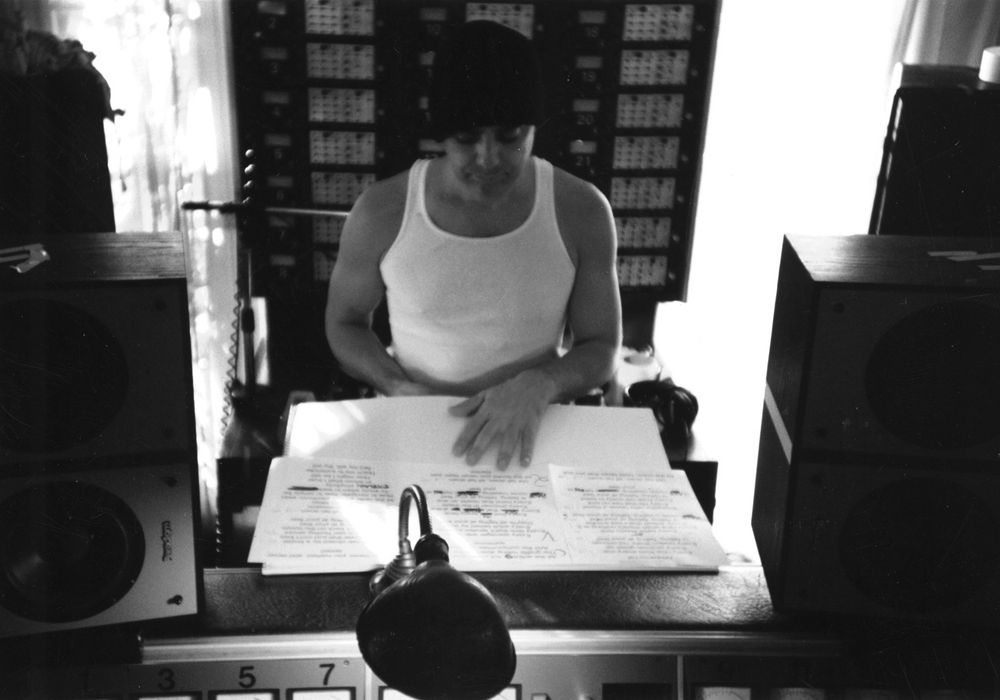

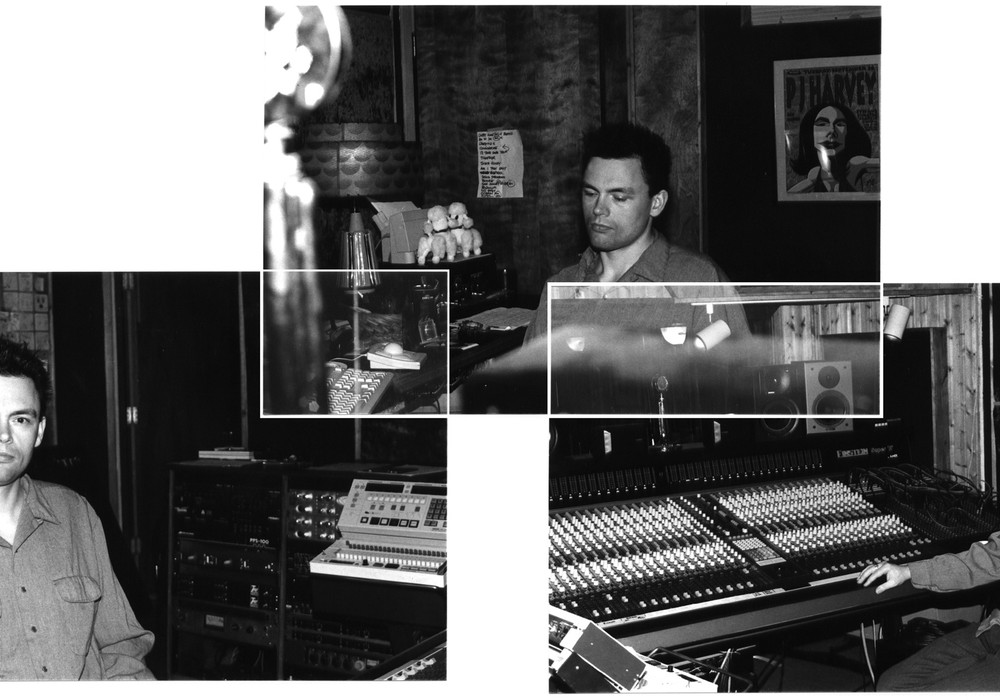

When we got a chance to drop for an interview with David Byrne, he was joined by engineer/producer Pat Dillett, with whom he had just completed the Here Lies Love album, as well as worked with him on the Brian Eno collaboration CD, Everything That Happens Will Happen Today and earlier on David's excellent Grown Backwards. I thought I'd seen Pat's name on album credits, but a little research dug up a history of work with Mariah Carey, Mary J. Blige, Nile Rodgers, They Might Be Giants, Doveman, The National and Emanuel and the Fear, plus a bunch of Brazilian albums with artists like Caetano Veloso and Marisa Monte. This seemed crazy and all over the map — so I had to find out more! Pat had a comfortable studio setup at Kampo Studios when we met, but when Kampo sadly closed in February 2010, he lost his space. Currently he's in the process of recapping an SSL E- Series console and putting together a new space to work from while keeping busy with many sessions.

What was it like mixing Eno and Byrne's Everything That Happens...?

We would get the tracks, and I would send the mixes to Brian while he was in France working with U2 [on their No Line on the Horizon album]. We sent four the first time. I was like, "Let's get a bunch of them done so at least if he hates one of them I won't feel totally freaked out." The first response was that he loved all of it, and he had very effusive praise. I told a friend of mine that I grew up with — "Brian loves it." He said, "Well, if you can't mix for Brian Eno, who can you mix for? That's all you listened to growing up!" By the time we were ready to mix, there were a lot of decisions made already about arrangement. So it was really just a sonic mix — good, old-fashioned mixing. Some of the very cool effects on that record they had done with analog and built in — they were part of the tracks. Some of the effects we did. I would send MP3s to Brian, and he would respond, usually very quickly. It was very intimidating and rewarding, because he would say things like, "Oh, I played it for Bono and Daniel [Lanois] and they loved it." I was like, "I knew I should have ridden that vocal more!"

They were probably there working on these U2 songs, and it's like, "Stop! Listen to this."

They worked on their record for a long time. I am sure they had a process of taking breaks of that sort. Sometimes he would send these detailed emails. I will have to print them out at some point. Some of them were hilarious. He would never say, "Oh, I hate that." It would be some description of the kind of person he imagines playing that sound. "I imagine somebody with very tight pants..." I would go, "Okay, he doesn't like that." Most of the songs were immediately liked, which was great. One of the first ones that we did was a song called "The Eyes," which didn't make it onto the record — it was a bonus track. It was honestly moving to put up the tracks and hear these guys. Brian sings on that one as well. It was pretty great to feel like, "This is exactly what I want to be doing." As an engineer you work a lot just to get those moments. There are very few of those, and this was certainly one of them. It was an extended, enjoyable one.

Were you mixing with automation or recall abilities?

Most of it is really in the box, but with a lot of hardware inserts. Some effects I would print if they were a little bit loose and squirrely, but usually the effects were recalled — I did a few things in the Eventide that I had to print because they are moving. I used a lot of the Sound Toys [plug-ins] for those oddball effects that I wanted to be able to just recall.

Were you mixing in Pro Tools or Logic?

Pro Tools. I know David and Brian work in Logic, but they converted most of the stuff, or we converted them when they sent them.

You mentioned mixing in the box. Are you summing internally?

I'm usually summing internally. With most of the mixing I do, I am coming out of the outputs and going to 1/2-inch [tape], which adds a nice image to it. But more and more than I expected, I take in the digital files and the tape and say, "Oh, I don't know which we'll use." I am usually mastering with Greg Calbi for David Byrne's work. He definitely likes the analog. I don't know if it's a prejudice. A lot of my stuff also gets mastered by UE Nastasi at Sterling Sound as well. He often will choose the digital. But on Here Lies Love there are 22 songs, and I think we used 14 from the analog and 8 from the digital.

Picking song by song?

Yeah. With the Byrne/Eno album we did it all from the 1/2-inch, but we didn't check each one. After a few we stuck with it. It varies from project to project. I like to have them both.

I was going to ask you in front of David Byrne, but one of the questions I had was, "How is David as an engineer?"

He's great. He brought a vocal in once for something that sounded really awesome and I asked him, "What did you do?" He said, "I used compression." [laughter] I looked at his track and it was crushing. It sounded amazing, but that's what he does. It's informed. He knew it sounded cool. His stuff is always fine. The only thing is — and I often tease him about it — he will often record his guitar parts with the speakers on. I can hear the speakers on in the close mic he has on his amp, which has never been a problem in a track, but it's funny when I solo it up. I'm like, "Hey, you cheated!"

What about the traffic noise he mentioned?

No, that's never been a problem. I think if he has it he's probably cleaning it out or redoing stuff if it's bad, because I've never heard it.

Are you working with lots of other artists who bring in stuff that they've tracked at home?

I've worked with They Might Be Giants for a really long time. They've been bringing stuff from home since the '80s. Whatever people may think of their music, and it's certainly changed a lot over the years, they have been trailblazers of the technical stuff from early MIDI to everything. They used to record stuff on 8-track at home and bring it in. Then they recorded on ADATs and D88s and we'd sync them up. They're actually both [John Flansburgh and John Linnell] really good engineers, and so are some of the other members of that band. Even Thomas Bartlett (Doveman) will do stuff at home because he has a keyboard setup and Pro Tools. Usually he will take stuff that we have already recorded band-wise, and he'll add stuff. Recording from home cuts across age lines. There are certainly younger people who are doing this who have had that access all the time. But David and They Might Be Giants are exceptions — they've been around for a while and they also embrace it. There is none of that, "Oh, I've got to get into the studio."

I think it's a great way for demoing and catching ideas, remembering stuff from the get-go...

Exactly, and being able to use it. For years it has been, "There is no such thing as a demo." It's really true at this point. This stuff all comes in and I try and keep them from overloading, distorting or ruining something on a technical level. But basically they are able to do these performances that are as inspired, or more so, as they could do in the harsh light of a studio.

On the other side of this coin, you have Mary J. Blige and the big jobs cutting vocals with somebody who doesn't want to record at home.

For every person I work with in that way, there is a different reason why they work that way. Mary works at home too. Her husband [Kendu Isaacs] is actually a great engineer and very into the technical stuff, but on a personal level it's just not smart for them to always do that.

"Get in there and sing that better!"

They are starting to do things with her that are a lot more... I don't want to say picky, but they are really working on detail stuff. I don't know if that's where I would necessarily go with her all the time, because what I love about her is how she really works up an emotion and a character for her songs. During the course of recording we would usually start with background vocals, stack them up and get a track for her of her own backgrounds. Then she would be ready to do the leads. They would be these incredible performances. The records that I have done with her — probably 75 percent of those are one performance, or one performance with a line fixed or something. Lately they have been doing some of her mainstream or pop stuff in a more polished way. I'm not being pejorative at all, but it doesn't necessarily shine the light on what I think is the most amazing thing about her, which is her delivery and her emotion.

The style of music and the sound of the backing tracks — I was like, "Oh, I don't know." But when I first heard her — she can sing.

She can sing, and she can reach people with that singing. Mariah [Carey] can sing too, and she has that capability of doing it in a way that is incredibly moving, but I don't think she always does it anymore. I think they've really, over the years, started turning her into one of these 10-track lead vocalists.

I think it's sad to see, because you are making a product more than art. I guess that's always been the case in this business to some degree.

And I think that the part of the business that they're in and to maintain who they are, that's certainly a valid way to go. But I think that probably both of those singers, later in their careers, will revert to more of a straight up performance with a band and really deliver it. Because they can deliver it.

Get some live players.

Chaka Khan — she's still around and she's off the wall. She can go nuts. It's great. But this diverse work I've done is all a byproduct of coming through a studio at a time when you did what came in, and by working at Skyline [Recording Studios, in NYC] where I started — they were doing everything from jazz to R&B and eventually hip-hop. I have a toe in a lot of different pools.

How long did you work there?

I actually was fortunate to be there and fill in when they needed somebody at all the right moments. I had one of the shortest tenures. I came out of college — not audio school, regular college — and was a toilet cleaner guy for about a year. I was assisting for about a year and then I was engineer. It was all just because they built another room, needed more assistants and I had been going in late at night with friends, pushing all of the buttons and learning how to do stuff. I got started engineering because they put Mariah in the MIDI room where they were supposed to be programming. We all got comfortable together and she was doing vocals in there, and suddenly I was mixing part of that record [her self-titled debut].

Had you had experience before taking on your first job there?

No. I played guitar poorly and I had been in some bands.

What led you to look at that field?

Between my junior and senior year of college at Georgetown, in D.C., my friend knew I was into music and he knew someone who worked for Nile [Rodgers]. They were like, "Maybe you can get a job working at the studio for the summer." I did. I loved it. It was great, and it was insane to be around that at that time. The day I graduated I threw everything in the car and came back up. I jumped in and started cleaning toilets and answering phones. Back then there were so many studios. I was lucky to be at one that was actually really good and wanted to be better. Our thing was trying to be like the Power Station. Power Station had a system — you had to be there for a long time. That's what Skyline was modeled on and it was pretty successful. You had to be ready to go to each level, and luckily I was. I was at that place at the right time, but I probably wouldn't have moved anywhere near that quickly if I was at Power Station. There were some guys there that assisted for three to five years. In those days that was a really long time. Now it's like some people assist a long time because there are no other jobs.

Who were you watching work at Skyline?

We got a lot of the Power Station guys because of that studio being busy. Also, I think those guys came to Skyline because you get more respect as an engineer when you are not at the place where you started out. I worked with Neil Dorfsman, Malcolm Pollack and James Farber. Kevin Killen [issue #67] came through — he obviously was not a Power Station guy. I think he started at Windmill Lane. Everybody who was really good in the late '80s was coming through for at least a small session. Ed Stasium came through for a while.

Some great people to watch at work.

It was one of the better places. They had two major rooms, and Nile [Rodgers] was always in one of them. I remember one time Nile had all of their rooms booked — their MIDI room and all their other rooms. I was recording Diana Ross MIDI basics in one room and they were recording The B-52s downstairs. There was a Hall & Oates session that he was producing for a movie in another room. I am sure at the time Nile would not have picked The B-52s [Cosmic Thing] as the one that would be the most successful.

No one expected that. You've lost your guitar player, you've been around for a while...

Now your drummer is your guitar player. "Deadbeat Club" is one of my favorites. They are super nice people too — really fun. I was an assistant and I did a little bit of engineering, but not much.

How was it working with Nile?

Nile is really great. He's one of the best musicians I've ever worked with — something he really doesn't get enough credit for because of everything else he is associated with.

What happened after Skyline?

I was an in-house engineer doing a lot of Mariah stuff. When she was not working, I would be assisting. I got to assist on a James Taylor record. I met They Might Be Giants a little bit before that — some of their stuff I would engineer on the side. Basically the studio encouraged me to go. If I was getting paid as an engineer through the studio, it's a lot of money for them to be paying somebody on their staff. At some point I launched off to do stuff with Arto [Lindsay] in Brazil.

Had you met him through the studio?

Yeah, they had done Ambitious Lovers stuff there with Roger [Moutenot, issue #20] for a long time. It basically became clear that he needed somebody to go to Brazil and do that half of the record.

You mentioned the studios felt like they were in a different era.

I guess some of them were. Some of them were newer. I used to joke that it was where SSL would test some of their products. SSL had put in their first G-series down there — not the first, but the first in Brazil - at a place that we ended up working, and we thought, "Oh, this will be cool." I ended up having to record the basics for that record with almost entirely [Shure SM]57s, because this studio had spent a lot of money to get the SSL and they didn't have a lot of outboard. It came out really good. There were definitely times where they were eager to do new things there, and it was great to be able to be part of — I'd feel bad if I was one of the only examples they had at the time of people coming down from the outside. I am sure I wasn't. But doing that level of work that Arto was doing was sort of new — not just the method, but the attention to certain details that was not common. It was sort of an accepted way of studio work that was in place there that was not the way we ended up working. We would do a lot more with unusual sounds or individual focus. There was a huge live scene down there — a lot of band-oriented stuff. I'm not 100 percent happy with the sounds I got at that point in my career and at that situation, but it was interesting. I went back at least once every year for about 11 years after that. Just seeing the improvement of their basic vibe of how they work — improvement meaning something I was more familiar with.

At various studios?

Yeah, not just that one. There was a place called Nas Nuvens in Rio [De Janeiro], which was great and run by a musician . He had an old Harrison console and a lot of API outboard in a very cool, vibey studio. He was way ahead of the game down there, and we worked a lot at his place. There were people who were doing good work, and then there were more of them. There was the rise in the awareness of the people and musicians. I am not taking credit for that — just watching as it became a more modern and looser recording environment — more artistic studio work rather than documentation work of just recording what's being played. Arto — his whole thing is about getting the right people and getting the people to bring their thing to a song. It was a production style and not necessarily technical. There's some great stuff that has happened since. Unfortunately some of the people who were really the best at it — like marrying hip-hop to Brazilian styles — have passed away. Chico Science was one of them. Tom Capone was an engineer and producer who passed away in L.A. after the Latin Grammys a couple of years ago. With somebody like Marisa Monte, it's as if St. Vincent is suddenly selling six million copies. It's a huge sea change that has a foot in an old style, but it still incredibly new and everybody likes it. It's not like Alicia Keys or something that is just a really good version of something you are familiar with. I would gladly do more there.

Was it hard to be away from home? Did you have relationships or home life that was getting strained?

I was married two different times during that stretch, but it was certainly more my own fault than anything that came from that. I was never really down there for more than six or eight weeks at a time. I would be down there often just for a couple weeks.

When you were doing a Brazilian record, would you bring it back here to do more stuff and mix?

We would do a lot there — almost everything sometimes — but we would always mix here, at first because it was the only way to have the equipment and the capabilities we wanted. By the end we could have mixed there, but at that point I was certainly more comfortable in the rooms that I mixed in a lot.

Where were you working when you were back in New York?

I would go back to Skyline and I would come here [Kampo]. I have only been in-house here for a few years, but I have been using the downstairs studio since 1989 or '90. It was always one of the most artist-friendly and cheaper places because of its mission of helping out people. I would work at Magic Shop a bunch. We did some of those records at RPM when that was still open. We would occasionally go to places like Right Track or Power Station, but usually not for those records. Skyline was probably as high-end a place as we would go.

I have seen a lot of people in a position like yours find a place to settle into and work out of so they can keep the overhead in check.

It's the only way. You certainly have to attach to some space. When I actually started being in the same place all the time, which is now probably about seven or eight years, I guess I got more work, but it's with the people I already worked with. It's easier. They knew where I was. It's sort of suicide these days to say, "Okay, I am ready to do it next week. Let's book a studio." I mean, it's really hard. You have to have some place and it can't cost more than you.

With the Doveman record [The Conformist] — what kind of budget does that have?

That budget is calculated purely in my good will. [laughs] I basically do that for free because I love Thomas' work. I get something on the back end if it works out, but that's not really a prime motivator. The time was fantastic, working with all the different people that were involved with it. Thomas is on The National's record label, so they played a lot on it. Dawn Landes, Norah Jones and Glen Hansard from The Swell Season and The Frames sing on it. Thomas is one of those guys whose stuff is more popular with the musicians that he works with and that know him than with the general public.

If musicians are the first to pick up on something, a lot of times word will start to spread.

It's ready, it's legitimate, it sounds really good, the musicianship is good and the songs are amazing. It's ready to be found. I just mixed an album [Listen] by this other band, Emanuel and the Fear. They're great. It's one of those 12-piece groups with the full, crazy arrangements, but really rocking. Many younger bands don't have budgets at all or can barely afford stuff. I did that for relatively cheaply too. It's something where, if you haven't done anything yet you have to do stuff for free and get people to know you. If you have done a lot, you need to do some stuff for free to make sure that people don't forget you.

Some of the artists, especially an independent or younger band — are they a little shocked when they figure out some of your recording credits?

It's interesting. I would think there would be more of that. Some people are surprised when were are talking about stuff and I say, "I worked on that Queen Latifah album." It would be nice to be able to sit here and say, "You will look at my discography and definitely find something you like." I can say that, but I can also say, "You will look at my discography and definitely find something you hate." I work with so many different people, you are bound to not like something. There is no logical sense except trying everything, being busy, being interested in a lot of stuff and being open to it. That has probably hurt me in some way financially over the years. If you even know who I am, you don't say, "Oh he is the guy who does that." If you are one of the top two or three calls for any style of music, you get all of it. But on the other hand I've probably kept busier than some other people, because when hair bands are out, that's not my only thing. It's having the Brazilian albums, the connections from my hip-hop and R&B days and the downtown New York rock stuff — it's different — the cottage industry of They Might Be Giants and doing a lot of their children's records. I would love to present this as being this eclectic deal where I only work with people who I think are really great and I really like them. But there is also, "He's just working." Frankly, if you have worked in New York for 20 years, you have done hip-hop. I have had some of the best times with that stuff. Back then when I was working mostly with The Notorious B.I.G. or somebody like that, people were into doing whatever on those records. It was like, "Great. Let's try it. Let's flange everything!" That was the wild frontier. Like what Brian and David do, especially effects-wise, that's the kind of thing I love that's wide open. That's where it was. It was in hip-hop then.

There is a lot of room with that. You can get atonal. You can do crazy shit.

Now that road is getting a little bit worn. There are a lot of formulas in that as well, like with anything. But working with Arto — he is a "do something crazy with this section" guy. There's definitely that thread of all of them being open to do whatever. Some of the people I just do vocals for, that is less so, but even Mary J. Blige — I have done a couple mixes and I have done some weird stuff, and they love it. As an engineer you have to find where you can make the opportunity to make something exciting.

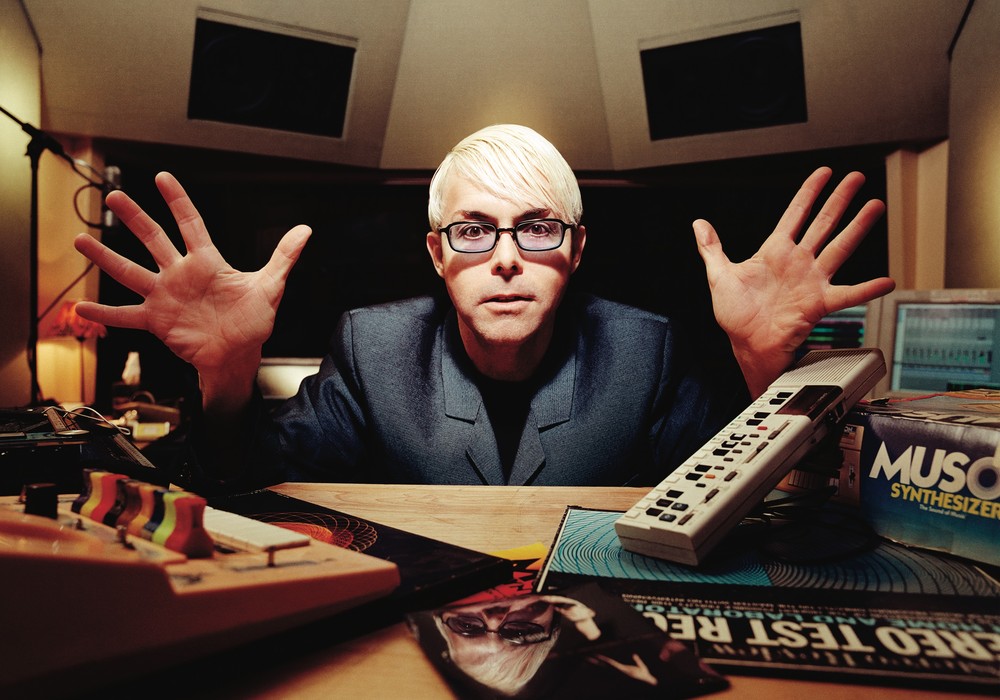

patrickdillett.com

visit www.tapeop.com for Pat's thoughts on digital recording and mixing