Gerald "Jerry" Casale formed Devo with Mark Mothersbaugh and his brother, Bob Casale, in Akron, Ohio, in 1973. The band went on to record some of the most creative, subversive and often abrasive music of the '70s and '80s, eventually scoring a major hit and controversial video with "Whip It" in 1980. I caught up with Gerald and Bob "Bob 2" Casale during a lunch break from working on some new Devo songs at Mothersbaugh's flying saucer-like Mutato Muzika studio complex in L.A. Working with fraternal co-producers Paul & Josh Hager, the band navigated difficult calendar logistics (Mothersbaugh and other members are incredibly busy with film soundtrack and music production work) and its first album, entitled Something For Everybody, of new material since 1990's Smooth Noodle Maps came out this summer.

Do you guys use demos, or do the demos become the masters?

Gerald Casale: Elements of the demos often become masters. We don't have the same demo-itis that we used to. There are demos where nothing could ever be as good, and the reason is the excitement is felt when you create something. It's embedded in those particular tracks, and so it's a subjective relationship. When you hear something new, those from the outside that never heard the demo might like it fine, but some of the essence is missing. Even if it gets down to an effect or an EQ on a synth that made you like the song, you can't get it back again.

I suppose lately it's become easier to keep the demo and massage it.

GC: Which is good! It's nice to keep the raw element, the creative inspiration in there because everything can get too slick and too cleaned up. It becomes sterilized and not what it was. A lot of Devo is about the combination of dirty and clean. We've been accused of being namby pamby and Disney-esque, and then on the other hand being Nazi clowns. That comment was actually the inspiration for Oh No! It's Devo, where we said, "Okay, let's make music that sounds like Nazi clown music." That's songs like "Peek-A-Boo!," "Out of Sync," "Explosions" and "That's Good." I really like that record. I think other than Freedom of Choice, Oh No! has become my favorite record. Who was it recently that was asking to use "Peek-A-Boo!"? Microsoft for some commercial?

Bob Casale: A series of commercials.

GC: We were considering re-recording it since Warners owns the masters in perpetuity, but when we went and listened to it we realized how difficult it would be to do a sound-alike. We said, "No, let them use the master," because it's incredibly, perfectly fucked up. "Peek-A-Boo!" really is one of the most ridiculously fucked up mixes, but it's great.

How did that come about? Were there happy accidents?

GC: Yeah, a bunch of accidents.

Josh Hager: The first record [Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!] you did in Germany in some village?

BC: A village is right. [laughter]

GC: It was outside of Cologne in a place called Neunkirchen, and we were staying in this bed-and- breakfast type hotel that was a couple of steps up from a student hostel. There was no central heating, like everything in Europe. We were there in the winter under big down comforters, and we had to get up early in the morning because the schedule we were on was absurd. We'd get picked up and driven over the frozen tundra into this studio that was a converted barn in the country. The studio owner [Konrad "Conny" Plank] had a wife [Christa Fast] and kid, and we'd all eat breakfast with them in the morning. It was a selection of heavy meats — processed meats, sliced like Monsanto floor tiles. We didn't know what the hell it was, but they had a huge array, and this is how we started our day. It was insane.

What was the studio like?

GC: I don't have a big memory of it. It was drafty.

BC: It had a Harrison board. They had a room that wasn't that large for the live room, but we pretty much set everything up in there and recorded all of the basics together live. I think the basics were done in two days.

Did you put up a lot of baffles?

GC: Not too much.

Did the whole isolated experience enhance productivity at all, or was it a bummer?

BC: Well, for one thing the weather wasn't much different than what we were used to in Ohio. [laughter]

GC: I do think that being isolated with no distractions probably was a good thing, because all we could do every day was work hard and concentrate. Obviously we produced an extreme-sounding record. It's so extreme-sounding that it's hard to date it. You don't hear it and go, "Oh, that's what they all did in 1978."

Exactly. [laughter]

GC: At the time there was mostly disco and lightweight stuff, middle-of-the-road ballads and English punk.

JH: Billy Joel was big when that record came out.

What was it like working with Brian Eno [producer of the first Devo album]?

GC: It was funny because Brian had worked through his Roxy Music phase and was into ambient stuff by then. He had done Music for Airports. He was into beauty by the time he got around to producing Devo, which was pretty strange because Devo was about this brutal, industrial aesthetic, especially then. He kept trying to find melodic and beautiful things in Devo, when at that point we had lived with these songs so long that we weren't interested in re-thinking them that way. It sounded ridiculous to us. He was getting super frustrated creatively, because we would shut him down on that stuff. He would do all of these beautiful melody lines and sing and then we'd be mixing and we'd be like, "No." [mimes pulling a fader down]

Did his ideas did actually get tracked?

GC: He made it into "Uncontrollable Urge." That's him singing "Aaaaaaa ohhh." He's in there, and I think a synthesizer track or two of his is in there too.

But after that album you lost touch with him?

GC: Yeah, he wasn't thrilled with the working experience. Bowie was supposed to have done it originally, but ended up being busy. I think behind the scenes Bowie said, "Hey do this for me, will you?" We don't know how into it Brian was. But the important thing he did and the most incredible thing he did, was he put up $40,000. He put up the money knowing that we would get a deal and then he would get his investment back, plus a lifetime of three points on this record. That allowed us to make a better deal with Warner's because we weren't asking to sign until they heard the record. He did us a big favor.

What were your first experiences with a synthesizer?

GC: Well, Mark put together a kit from PAiA, and after that we moved right up to our ARP Odyssey and a Minimoog. We got stuck with that setup for a long time. Most of Devo was created on those two things.

There's a lot you can do with those.

BC: Between the two of 'em.

GC: Actually, those were probably the two most reliable synths for live applications. Tuning wasn't very reliable. [laughter] We'd tune them up and then the stage lights would come on, and it would be a whole new temperature onstage and tuning would go somewhere else completely.

BC: Well, the earliest Moogs, even the three-oscillator ones, wouldn't track with each other. Tuning was like a 20-minute ordeal.

GC: Oh yeah. I remember a lot of that.

JH: Did you have any backup synths with the roadies tuning?

BC: No, we didn't. We couldn't afford it.

GC: We didn't have backup anything.

BC: The ARP, on the other hand, would stay in tune. But the keyboard was so cheap and the contacts they used for the keyboard were so bad that almost every night some key would stick on. So you got this one, whatever sound you had up there that would keep going.

GC: Not as bad as the [Electronic Dream Plant] Wasp synths. BC: The Wasp was great!

GC: We loved the sound of the Wasp and we were so excited about the Wasp that, in a suicide move, we used them onstage during the Duty Now for the Future tour. As soon as any drip of sweat from my head or hands hit this thing, it'd go "Bleewwwdawablawdwa!" I wouldn't be touching it, and it would be playing. Everybody on stage would be looking at me and I'm like, "But I'm not playing it."

BC: We tried a lot of things that were suicidal. Do you remember the very first wireless units that Nady put out? They were two different receivers with FM

tuners on the front, and you tuned them so that one would pick up if the other one lost it. Well, we bought four of them, had never used them before at all and decided to use them in front of 105,000 people. Of course it was very erratic — one song the vocal worked and one song the guitar worked.

Is there any new gear you like?

BC: We haven't gone to the NAMM show for a couple of years. We've had people go down and check stuff out, but there's nothing spectacularly new.

JH: Have you been discovering old gear at all?

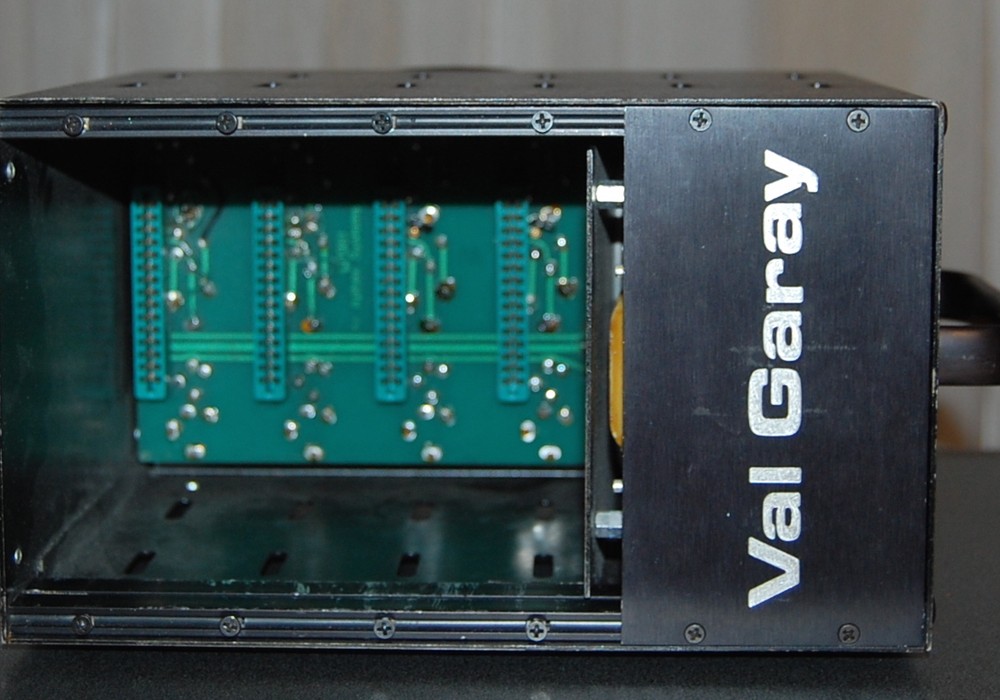

BC: We still have it. We've got one piece that's so fucked up, but we always use since it has the best noise filter and noise generator. There are wheels missing and the keyboard slides back and forth, but you can still actually use the filter and make it sound right. We have had that out. It does very odd sounds.