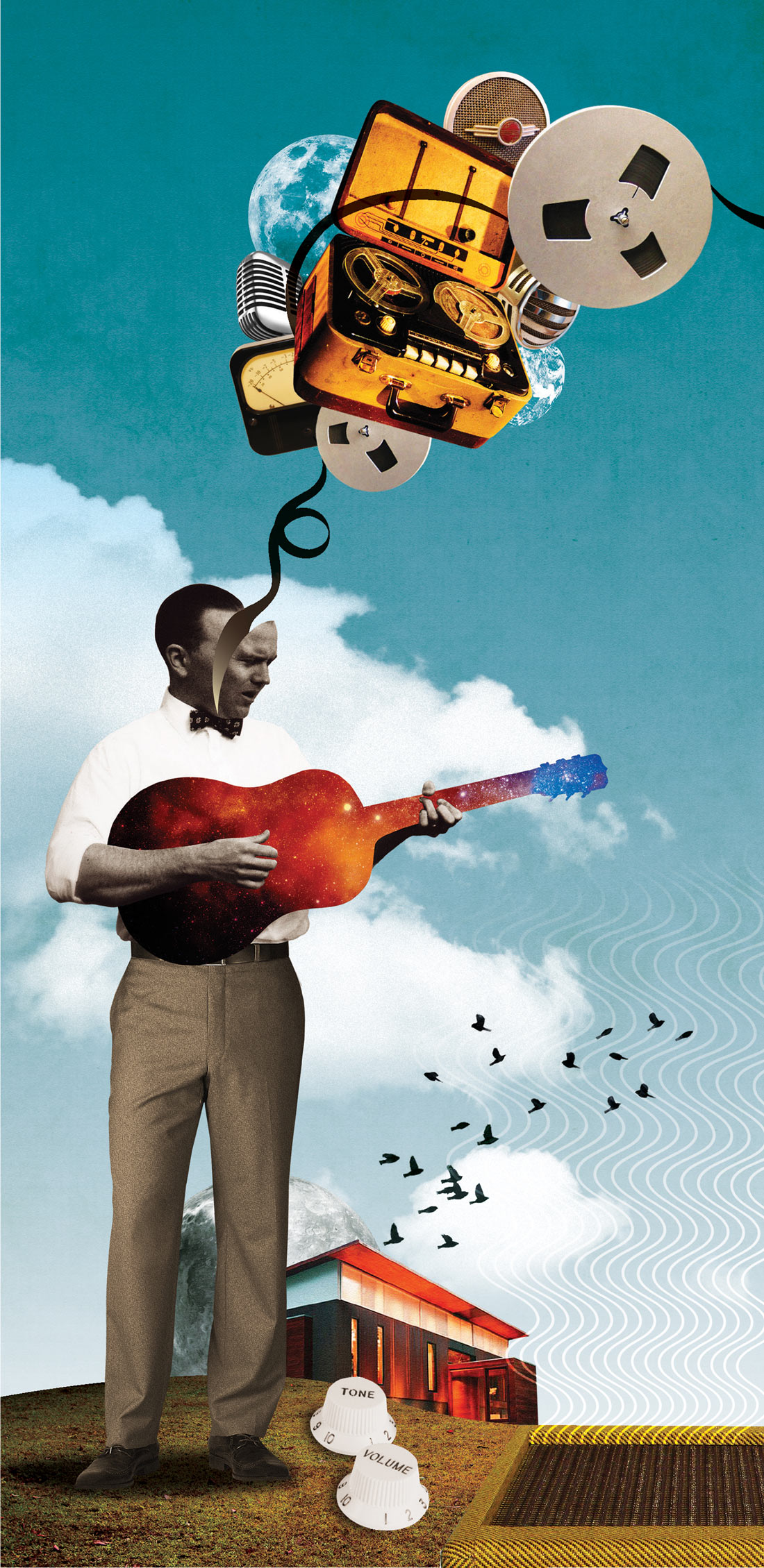

A sampling of the artists Robert Musso has recorded (or mixed) gives an idea of the stratospheric world he inhabits on a daily basis — Ornette Coleman, Bootsy Collins, Buckethead, Herbie Hancock, Iggy Pop, Carlos Santana, John Zorn, Sly & Robbie, Pharoah Sanders, George Clinton, Master Musicians of Jajouka and the Dalai Lama. But these names aren't isolated high points in his life. They are part of his day job with Bill Laswell. He has worked in every major studio in NYC and intimately knows many others worldwide — from George Martin's AIR to Compass Point in the Bahamas]. Musso, in his duties as an audio engineer, has been producer Bill Laswell's right-hand man for a quarter century; but you can frequently find Musso the guitarist playing extreme avant-noise with such stellar downtown NYC improvisers as the late Sonny Sharrock or Ornette Coleman, while deftly overseeing the recording and release of DVDs of scores of these types of events through his MussoMusic digital distribution company. Robert is also an educator at the Institute of Audio Research. Musso's personal discography, as an artist and producer, includes various albums with his infamous Machine Gun ensemble, as well as many solo projects and collaborations on various labels, including his ambient Transonic series of CDs.

How did you hook up with Bill Laswell?

The first time I worked with Bill he was at RPM Studios in New York City, and the engineer he was using didn't want to work on Labor Day, 1982. My roommate was a maintenance engineer at the studio and I got the gig. I was like, "I'll work on Labor Day, no problem." They said, "There are some crazy kids that are trying to do some different types of club music. They're part of this whole downtown music scene." That's how Bill and the Material crew were described to me. What was great about that session was that in one five-hour period, we recorded Archie Shepp on saxophone and Whitney Houston singing — the first time she had ever been in a recording studio. She didn't like wearing headphones because she was used to singing in church with a choir. When she first put on headphones, it took a minute for her to get used to it. No one cared because she sounded so great. I turned Bill onto doing a "fly in" in that session. They wanted Archie to play at the beginning of the song, but he didn't hear it. So he played the solo in the middle; I think he played the end also. We recorded a couple of takes and I said, "Why don't we fly one into the intro?" I knew they were the same chords. Bill asked, "What do you mean?" I said, "Let's record his saxophone from the multitrack tape onto a piece of 1/2-inch 2-track tape," which we did. Then we rewound the multitrack tape to the beginning of the song where Bill wanted Archie to play. We played the song and put the multitrack into record and I played the 2-track — I started it at the right spot and flew his saxophone from the 2-track to the multitrack then into the beginning of the song where it never was before. I think Bill was kind of blown away by this because he had never seen anyone do that and it worked out well. That's the reason he started using me. Recording Archie Shepp and Whitney Houston and mixing the song "Memories" [written by Hugh Hopper] on Material's One Down — that was my first day in the studio with Bill.

When I first met you guys, you were working at Platinum Island, Quad, Power Station and those kinds of high-end places, mixing on SSL consoles. Later, at Greenpoint Studio, you were mixing without automation and doing a lot of tape splicing. I doubt anyone would ever imagine that anything as complex as Material's Hallucination Engine was mixed and tape-edited by hand.

Automation was there to supposedly help you make mixing the record easier, as well as to be more accurate and repeatable. The problem was that it took a lot longer to use. The computers were slow and sometimes it wouldn't work; sometimes to the point that I spent a lot of time and sweat on something and then the console would break down and I would lose the automation. It was frustrating. I said, "Let's do this the way they used to. Let's mix in pieces, take a very small portion of the song and focus on getting that section sounding great." The way we worked at Greenpoint, and continue to work to this day, is to set up the mix on the introduction to the song. We only listen to the intro and we refine the elements of the mix on the introduction to the song until the introduction is perfect. When it's perfect, we record it to 2-track. We used to record onto 1/2-inch tape. Now we record it to Pro Tools.

Then we go to the first verse and we only concentrate on the first verse, get it perfect, record that and then edit the two sections together and continue mixing that way. You do that from the beginning to the end of the song — spending a lot of time listening to sections and making sure that each part is correct, recording each section as you go along and keep editing them together. If we listen...

_display_horizontal.jpg)