British superproducer, Steve Lillywhite, CBE, has spent more than three decades helming storied recordings by artists like U2, Peter Gabriel and the Dave Matthews Band. Fresh from his latest work producing Matthews, The Killers, and the "Music From" album of Broadway's Spider-Man: Turn Off The Dark, Lillywhite sat down with me in New York City to talk about his fabled career atop the pop charts.

Did you start out as a musician?

I started out as a bass player, but I was 16 years old, before I got a job in a studio. I started off as a tape op in 1972 at Phonogram Studios — a record company- affiliated studio. It had one studio and two copy rooms for the record company. I think there was a staff of 11 people, which was ridiculous. We had three full-time tech guys, who all left for the suburbs at six o'clock every evening. I really was a tape op, more so than probably any other single person in the music business, because the studio that I worked at was the last one in the world that had a separate machine room. You had the control room and my room was called Room B. I had a little Auratone speaker, a swan-neck microphone on the desk, and a window so I could look up and see the engineer. I sat next to the tape recorder and he would give me commands to start and stop. A drop-in or punch-in was called a "cue to press." I would just sit there for hours and hours, days and days on end, rewinding. I was told that I could never be part of the conversation in the control room. If they were having a joke in there, they shouldn't suddenly hear my intercom piping up. I was told to be humble. I would sit there listening to the tape, and if I thought, "Oh, maybe they'll want to do the second verse again," at the end of the song I'd go right back to the beginning of the second verse and park the tape. They'd be discussing it, and they'd go, "Okay, can we do the second verse again?" Boom! I wanted to be the fastest gun in the west, because it was such a simple job. That was literally all that I did. I would run the 2-track for mixing. I would also run the other 2-track machines for delays, and things like that. We would always run the EMT plate [reverb] through a 15 ips tape delay.

Going in?

Yeah, going in the front. It was a great learning experience. I wasn't very good on the technical side; and I didn't understand engineering for a long time, because I was never in the control room. I wouldn't be here today if it weren't for my boss giving me a chance. At other studios tape ops would learn to engineer by watching. I couldn't do that there, because I always had to be at my station. On weekends we were allowed to take our own projects into the studio to learn. I would literally be trying to do something in the control room, running into the other room to record, and then running back!

So you didn't have your own tape op?

No. Occasionally a member of the band would do it for me. Working on the weekends I managed to do some demos with a band called Ultravox that got them a record deal. I took a couple of weeks holiday from my job to do the debut Ultravox album.

With that Ultravox record [Ultravox!], Brian Eno [Tape Op #85] was producing as well.

Island Records signed the band and said, "Who's Steve Lillywhite? You need to have someone else come in." I'd never made a record before, so it was quite understandable. The band said, "Well, we like Roxy Music." Brian is a fantastic man. He doesn't spend all his time in the studio, but when he's there he really utilizes it. I'm much more involved, and I micromanage like crazy. I tried to be that Rick Rubin sort of "sit back and see the big picture" guy, but I have to be in there getting my hands dirty. But that

was the first time I'd met Brian, and then I didn't see him again until [U2's] The Joshua Tree. I get on really good with him. He's one of the brainiest people in the world. We have a great relationship.

Did you keep working at PolyGram's studio?

I eventually ended up leaving that studio and took a pay cut to go to Island Records' studio in 1977. That was when I first got to know Chris Blackwell [Island's former head], who has been an absolutely fantastic man, and a mentor to me in a lot more ways than just music.

Have you collaborated with a lot of other producers?

Not really. I didn't collaborate with Brian Eno on the U2 albums that much. I didn't really produce those, with the exception of [How to Dismantle an] Atomic Bomb, which I did produce, in a different way. For The Joshua Tree, Achtung Baby, All That You Can't Leave Behind, and No Line on the Horizon, I've always been brought in at the end just to help finish it off.

So you're not working together?

No. What's great is that the band will do something and then Brian will take the tapes and go into his little room, take all of the organic elements of U2 out, and replace them with Brian-isms. Then I'll come in and take what Brian's done, but I'll go back to what the band originally did, and I'll try to make sense of it all. They love Brian's hatred of anything rock. That's Brian's job, to hate U2. And they like that! He loves them as people, but in general he's not a big fan of rock music. He'll take the guitars off and put drum machines on. I'll come in and use a little bit of what he does, combining it back with earlier, organic stuff. We try to make things a bit more unique. I'm well aware that bands have to live in a certain world, and there are people who want to hear guitars on a U2 record.

You worked with Hugh Padgham, who went on to produce as well.

I only did three albums with Hugh Padgham. He was my engineer, and he is really a great engineer. That was with Peter Gabriel [his third album] and two XTC albums [Drums and Wires and Black Sea]. I love Hugh. He's great.

Here's a question from Larry: Many of the artists you started producing with had a definite sonic identity. Ultravox, XTC, The Psychedelic Furs, and Peter Gabriel. Do you look for that in a band?

That's not the first thing I look for. A lot of producers will tell you that it's the song, but for me it's not the song. Obviously you've got to have good songs, but if I don't hear a voice that I like I won't listen to it enough to like the song. For me, and probably to most people, a song is something that you have varying emotions about. Sometimes you can hear a song five times and go, "Why is everyone raving about this song?" Then, the sixth time you hear it, you say, "I love that song! I never got it before." If I like the voice I rarely change my mind about it. If I like the voice, then I'll give it a listen, and go, "Yeah, there's something in that song that I didn't get the first time." I'm aware of my failure to choose a hit song right away.

If you're spending weeks in the studio, you'd better like the singer!

I love a challenge, especially if there's something that sounds unusual. I did a band called Guster; when I worked with them, the drummer didn't play on drums. He played on two acoustic guitars and bongos. When I saw them, they were fantastic and it really worked. I figured my job was not to say, "Okay, you've got to have real drums on this." My job was to ask, "How can I take what obviously is working, and then put that in a medium that I'm supposed to be an expert in?" It's like the Dave Matthews Band. When they first came out and were starting to blow up in '93, a lot of producers, including my good friend Hugh Padgham, said, "You can't have drumming like that! No, it's too jazzy." But I saw something there, a connection with the audience. My job is to communicate that in a format that people would like. I think I'm good at that. I'm not a boat builder. I'm the captain of the boat; I can help to steer it and decorate it. I've never written a song in my life, but I can steer it safely to port. I always want to work with the best ship builders. Why would I want to work with someone who isn't very good? I want to do as little as possible! That sounds bad; but I think that I'm my best with the best. If I drop my standards, I won't end up doing as good of a job. Take a group like the Dave Matthews Band. You've got to be very good at what you do to want to change what they do, because they're a fucking great band.

Are you more of a music fan than a musician?

No. I'm a fan of the people I work with. For me, it's a very big decision to work with someone. I always say that I don't like music, because I don't listen to a lot of music; but I suppose I am a fan of music.

You're a fan of good music?

Yeah. I try not to put things into formats. For me, there's just good and bad.

I get the sense that producers are almost becoming the de facto A&R people now.

Well, for a start, there are very few people. Don't you hate when A&R men said, "I made that record?" I hate that! They talk like, "When I made the so-and-so record." No, they didn't! They came to the studio twice and took us out for dinner. But, of course, their bosses in the record company don't understand what we do. So, for them, it's like, "Well, he made that record, so we've got to keep him." Of course the producer is never in those meetings to say, "Wait a minute, that was me!" We get fucked over by record labels. I've been to radio stations and seen gold albums for records I've made given to the DJ. I don't even have that gold album, but the record label gave it to the station for playing the songs!

You already did your job.

Exactly! And boy, don't they love iTunes, where we don't get credits. Anyway, don't get me started on that.

You've never really stopped working, have you? It seems like a lot of people who had a lot of hits in the '80s and '90s have slowed down.

Forty years. Divorce will help that.

Okay. [laughs] But you seem genuinely excited about what you do, still. You still have a passion for it. How do you maintain that?

Arrested development. Honestly, I think that whenever you're in the studio, life is on hold. I'm probably 25 years younger than I actually am, mentally, because of that. Also, I don't treat it like a job. In a job, you have your work, your sleep, and your play. For me, and you know this too, I never get that awful Monday morning feeling, which is great. But then, you never get that elation of Friday night either, where work's finished. You miss out on both of those. It just is. You just do your thing, and a holiday comes. "Oh, it's July 4th and I'm in the studio!" You don't think otherwise. I never want to be complacent. I used to sit in my little room when I was 17, and I'd look through the glass window at the people in there, and there was a certain arrogance.

I'd think, "I'm never going to be like that." I was just angry that people were taking it for granted.

What concessions do you make as you're helping create a song? What if someone in the band wants to sabotage a song in a way, like, "Not too big! Not too hot!"

That used to happen a bit more. In the early days U2 had a song called "Pete the Chop," that seemed like it might be a hit. We never finished it because Bono felt that they didn't want to have that in their career yet. It turned into a B-side called "Treasure (Whatever Happened To Pete The Chop)." Obviously I listen to the radio, and I keep my ear out for what's going on. I listen to people who take the records to radio as well. I live in the real world, so I'm aware of that stuff. I don't live in a utopia where good just means good, and bad just means bad; but I feel that the parameters of my beliefs can work within the formats.

But the whole music industry has shrunk.

It has, but I still think that good will come out of it.

In 2002, you were working at Universal Music Group as a managing director.

Yeah. I wouldn't have done it if I didn't think I had something to offer. I also wouldn't do someone's album if I didn't think that I had something to offer. It's not what I've done before, but how I feel now. I hate it when artists say to me, "Steve, I'll do whatever you want me to do." I don't evenknowwhatIwanttodo!WhatIwantyoutodoisto give me ten ideas, and I'll help you get something great.

When I'm producing a record, the ones I look back at and like the best are the ones I didn't really plan out, where the mistakes happened.

That's also joined to a memory; the memory of that mistake and the fact that you were man enough to leave it in fills you a little bit with pride.

How important is it, as a producer, to recognize good mistakes?

I don't know what mistakes are! What are mistakes?

Well, when the band says, "Oh, we've got to fix that," and you say, "No, that's brilliant." I think a lot of artists tend to want perfection.

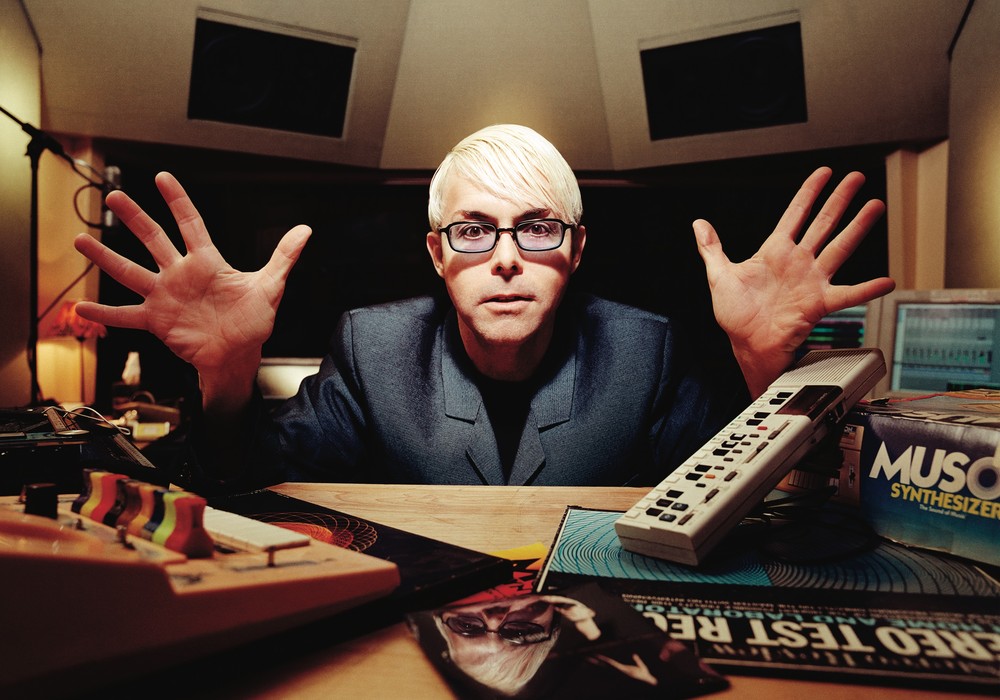

Maybe. Especially now, with how they look at music, instead of listen to it. I'm always listening. I don't look at the screen, ever. Part of that is because I really don't know how to work it. But I have people who do, and who know what the computer does. I have no interest in typing. I should take a Pro Tools course, because I'd like to at least be able to sit there and do a little fiddling on my own, if I wanted to. I think I was quite honorable back in the day when Pro Tools came out, because so many producers learned it on an artist's budget. I didn't want to do that because I felt it was immoral. I stayed pretty Luddite and analog. I initially went with [iZ Technologies'] RADAR, which was like a digital version of what I did already [with tape]. I mix with a computer now, but I always come through the desk because I like the sound of it. I'm also building my mix up right from the very beginning, and that is a tactile thing. I've got ten fingers. I've never made a record where I haven't sat between the speakers with my hands on the faders.

So, once you're mixing, you have an engineer helping; but are you still pushing and moving faders around?

Yeah. The way I've developed with Pro Tools is that I balance all the time. Whether it's backing tracks, overdubs, or whatever, I'll balance it and then I'll go over to the API EQs and fiddle on the console. I'll live with it for a bit and say, "Yeah, I like that." Then I'll replicate that EQ in-the-box and take the EQ off. The next time we put that song on, it comes up. All I have to do is set the fader level. I'll take photographs of the starting points of the faders, and then I'll do the rest by hand. That's how I mix.

When you say 'replicate it,' you're talking about taking those EQ settings and recreating them...

...on the Waves [plug-ins]. I've done those tests and they really sound good. Then I'll do some manual fader rides; if I like those rides, I'll replicate them. But I'll always mark my starting points. I'll be building up a mix manually; but the next time I put that song on, I just get the photographs out. I never use console automation. It's a pain! It's always owning you — you're never owning it. You always have to own what you're doing. You may have the best desk in the world; but if it's owning you, you become smaller than what you are. You become timid.

It's like trying to ride a bike and being worried about falling off.

Yeah. I don't want to be timid. As I say, I have my theories. I don't ever listen to records that I've done, because there's nothing else I can do with them! It's very passive, and there's nothing more you can do. You can only have two emotions: Either you like it or dislike it. If you like it, there's a chance that you might become complacent; and if you dislike it, there's a chance that you might become uncertain. Uncertainty and complacency are not positive things. Now, if I hear a song I've done on the radio, I think, "Yes!" This is an absolute fucking fallacy that record companies have been told; that you need someone to do a radio mix. The radio will compress it. The radio will make it sound like everything else. You don't need some guy to overdo it before it goes to radio! It's a joke, and these people have invented a job for themselves. I come from a point where I'm mixing from the moment I start recording.

As you're working on the desk, do you ever bounce that back into Pro Tools as a stem and then use that as an element?

I do that occasionally. I like to keep 24-tracks. I did an album [Set] with The Thompson Twins. It was very unlike me, not necessarily my sort of music. Tom Bailey, the main band guy, said, "Steve, as you make a record, the amount of choices you need to make should become less and less, until at the end you don't have to make any more choices because you've done it!" I always think that I take that as a concept, all the time. I try to think of my life as a 24-track. Danny Lanois [Tape Op #37], on The Joshua Tree, said, "Steve, if you can't do it on 24-tracks, there's a problem." I took that and I still live with it, even with Pro Tools. In my world, there are 24 tracks. Inside Pro Tools, it's an enormous fucking thing; but, from where I am, it's simple. I don't spread it out. I don't have a fader for every output of Pro Tools.

Right; you're never grappling with hundreds of tracks.

No! Keep it simple! Bounce it inside and gang it up inside the box. So many people now, young kids who don't understand limitations, just keep recording tracks into Pro Tools, and then they give them all to a mix engineer. I try to be fearless.

You've said that when you're working on a record and it starts to go bad, you can see it before it goes bad and steer it back on track.

Yeah, well, that's the captain of the Titanic. I would have seen the iceberg.

How do you do that?

Instinct. My personality is very good for my job, I think; although maybe I've made my job around my personality. I'm very much a people person. I think the difference between me and a lot of producers is that I'm very good with bands, because I'm good with people. I'm good at instilling a sense of teamwork, like, "We're all in this together." Also, when I look at a band, I can see the strengths and weaknesses straightaway. I know the mouthy guy, and I can tell you what instrument they play before they tell me. It sounds ridiculous, but I have that sense. Also, a lot of producers will say, "Here's the writer, here's the singer... that's the guy I'm going to have my special relationship with." I don't look at it like that. I look at maybe the bass player, who's a little weaker, or a bit insecure. The singer can look after himself. He doesn't need me to be all chummy with him. That bass player needs me. I'll go and make sure that I work with him more at the beginning to get his confidence up, so he can think, "Oh, Steve's my mate!" I try to keep things like that.

So you just keep it from going bad altogether?

Well, it can go bad; but I have a good sense of when it's happening.

What are some of the warning signs that it's starting to go bad?

If you don't have any vocals — a lot of people will work for weeks without any singing. It's like, "Hang on, we need to have a voice." There always needs to be something there that we're painting around. It might not be as much fun doing vocals as it is sitting there working on fancy guitar sounds, but it has to be done early.

I read that on the Marshall Crenshaw record you produced, Field Day, that you did your usual thing and realized that that was a mistake.

I felt that it was a mistake on my part, to do that to Marshall Crenshaw. Marshall, on the other hand, will absolutely say, "No!" He'll say that's what he wanted. History has been relatively kind to Field Day. It didn't sell very well, and wasn't deemed a success. But occasionally people will say, "Oh my god, I played that song, 'Whenever You're on My Mind,' at my wedding!" We all try to make timeless art. I've had some people say that I was responsible for the sound of rock music in the '80s. Even though I didn't make any of those big rock albums, people seemed to think that other records might have been influenced by a sound I was getting early on in the '80s. If I hadn't of been doing it... that sounds very bigheaded. You can argue anything, really.

I remember the point where I figured out to run a reverb through a gate, and it was like, "Whoa, it sounds like Big Country!"

Yeah, but we never did that — it was always just natural room sounds. Both Hugh Padgham and Peter Gabriel have claimed that "Phil Collins drum sound." But I can claim it far more, because I can tell you a lineage leading up to that that shows I was the one pushing the envelope.

Well, you hear it in your recordings.

Yeah, even before Peter Gabriel. You don't ever hear it in Peter Gabriel's records before me, or any of Hugh Padgham's records before me. I would say that my claim to it is probably the greatest. But everyone helped to hone it down. Peter would say, "Come on, try that!" It was on an SSL, from the compressor on the talkback. So whenever we pressed the talkback and heard the drums through that, we thought, "Fucking hell. That sounds great!" Then Hugh plugged up the output of the talkback, and that started it.

What are things that arise that cause your involvement in producing an artist's album to stop, like that one Dave Matthews Band or the Evanescence record?

Well, the Dave Matthews record was a strange situation. With Evanescence, I suppose that I was interested in the idea of Amy [Lee] as a great artist. When I was involved there weren't really many band members involved, so the record was a really interesting combination of electronic sounds, but it didn't have any power chords. I like that. Very rarely do you hear any power chords on records I've made. I suppose I was interested in seeing how she could take her music in a new direction. Maybe I was wrong, but I was thinking, "Does the world really need another Evanescence album that sounds like Evanescence?" I don't know — maybe it did. But what happened was a few people lost their nerve. I don't even think it was her. It was people at the record company who really had no other band. They were thinking more in terms of the commerce rather than the art.

You've said before that, "Art and commerce can coexist."

I've been part of a handful of records that have done really well, and it's never been talked about. Like, "We need to do this to make it a hit." I can absolutely guarantee you that when Fleetwood Mac was making Rumours, they were not thinking about formats. They did it truly so they could sit there, listen to it, and be proud of what they were doing. On the other hand, I don't think that music should be a government grant either. That's where my whole belief comes in of something being either good; not good, or varying degrees of good. I don't see there being anything other than that. I suppose I'm quite opinionated with my taste. Music has been the only thing I've done for 40 years, and I still believe in my senses.