Back when I was first starting out, all my friends' bands wanted to make their records with Lou Whitney. He was the first "Professional Recording Engineer" I ever met, when a friend brought me to Lou's Column One Recording in Springfield, Missouri. We toured the studio, and Lou was cordial, funny, and had plenty of good advice for a young engineer, (i.e., become a lawyer). As time went on we became good friends, and when he hired me to work for him at the studio and on the road with his band The Skeletons, it was the gig I had been waiting for. The things I learned there were innumerable, but mostly I loved his approach to recording an entire band live in the room and his fantastic sense of humor. He also writes a pretty damn good song now and then...

Where are you from?

Phoenix, Arizona. I went south to cool down in Tennessee. I had some brushes with the law when I was in high school, so I was sent to live with relatives in the mountains of east Tennessee. I finished up my high schooling out there, near Johnson City; a little town called Erwin. That was where I straightened up, so to speak, and met my first wife. I went to college there and moved back and forth from Arizona, but I finished college out there at different schools. I majored in business with a minor in real estate.

When did you first pick up an instrument and start playing?

I got interested in playing in Tennessee. The family I was staying with all played and sang. Relatives and neighbors came around and sang. There were guitars sitting around, so I started picking them up, learning, and asking people to show me songs.

When did you decide that your chosen instrument was going to be the bass?

When I was in college I played guitars with my buddies. This was in '64 or '65, so we said, "Hey, let's start a band!" We'd play mostly at parties. I was the least adept at playing solos, but I was a good rhythm player. We needed a bass player, so I thought, "What the hell... it's only four strings!" I had no interest in playing solos, but I wanted to be in the band.

The most interesting bass players are usually guitar players who were frustrated by the fact that there was a better guitar player in the band.

It depends on how you learn. I learned the guitar to accompany myself. The first thing I did was learn a song. You're accompanying yourself and learning chord changes. You'll be singing and then say, "Well, something's gotta happen here. It doesn't sound right." Then it's like, "Oh, it goes to the IV. It goes to the F." That's how you learn about chord changes. That's a really good foot forward for a non-trained, folkie-type musician who's going to play bass because you're thinking about chord changes and structure, as opposed to notes. The best bass players I've ever met in my life were all tuba players in bands. They understood bass clef inside and out, and there was nothing they hadn't met on sheet music.

So, it's '64 or '65, you're in a band, and in college?

I was in college full-time and working on the railroad, too.

I know you played with a bunch of show bands in Myrtle Beach.

I'm 70 years old now. Back then I was probably a little bit older than The Beatles' generation. The Beatles came in the fall of '63. I dug it and I got it. But I understood it more from an analytical standpoint like, "Oh, there are some English guys singing like the Everly Brothers, with accents. How cool!" I loved The Beatles, and Herman's Hermits, and everybody else until Rubber Soul came around. Then I got a little more out of it. But the music that moved me was R&B — Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Percy Sledge. That got my motor going, and that's what our band moved itself towards. We did show bands and backup bands for artists. We always had horn sections, and we tried to be the best band around. We played a lot of frat gigs all over the south. It was interesting, it was fun, it was informative, and above all it was educational.

I always loved the story of you being at the Sex Pistols gig in Tulsa.

It was Jim Wunderle, Donnie Thompson, myself, my ex-wife, Annette Weatherman, a woman from Springfield, a Harvard-educated girl we'd known forever who went to live in England in the formative days of The Clash and the Sex Pistols, who has some of the most amazing live Clash tapes you've ever heard in your life. I've got some of them right over here. The first shows they ever did, rehearsal tapes, stuff like that. So we drove down in Annette's Mercedes. It snowed about 17 inches. We went to a friend of mine in Tulsa's house to kill some time and then down to Cain's Ballroom where we saw the Sex Pistols backed up by Bliss. Bliss had hair down to here, guitar twin solos. They opened up the show, and then the Sex Pistols came out. Oh my god, I couldn't believe it. Out in front of the show there was a crowd of people waiting to get in and trying to buy tickets. We had ours in advance. Then a bunch of university students were there at the same time, decrying the fact that punk music was the music of Satan. If you go see the movie D.O.A., I'm in it and Donnie Thompson's in it.

You guys were all right up front, right?

Yeah, yeah. Later on in the show, I was back in the back, and Sid was walking around the room. I had a pen and I wanted to get Sid's autograph. So I pulled my pen out and went, "Sid, could I get your autograph?" He said, "Fuck off!" and he took my pen and never gave it back.

I can tell you that my assistant, Eddie Spear, I think he's going to be a rockstar. He's a drummer. That's my new deal. All my assistants have to be a drummer.

I've got an assistant from MSU, a fine educational institution about ten blocks from here. They have a studio over there and they have an audio engineering/music production type major. I used to take interns from there. The guy who signed them up is now retired, so it won't get him in trouble. The interns would come in, and I'd say, "Well, I'll tell you what. It's hard to assign a time to come here every day, like 3 o'clock, because I might work really late one night before and not even want to come in again until after 3 o'clock. Some days I do nothing, and others I work from 10 in the morning until 3 o'clock." But I gave them an open-door policy and let people hang around whenever they wanted to. I said look, "You're going to get an A. Come in every day and hang out all you want to. If you never come back again and I forget your name until I get the paperwork on you, you're going to get an A." Most people would not come in. The guy I've got now was in a band, and he really wanted to know about this stuff, but he was like me. He had mixers and stuff, had worked A/V at school, but he was the guy. He came here all the time, and he learned how to wrap up cables, how to put up microphones in the right box, how to respect the gear, and the more you hang around, by the time he'd finished his internship that semester that he'd made himself so valuable that we kept him around. It's like when you came in. There are really only two ways to get into things. Go into a school that offers a 4-year program with intern capability. Then you will be taken seriously. If you go to Joe's Recording School for 13 weeks, you're not going to be taken seriously. You will get a job at a studio, and your job will be emptying ashtrays, going and getting Cokes for people you don't like — the valet aspect is inescapable — and then they'll let you like put up a microphone. In England in the old days, you couldn't get a job as a pencil-assistant or tea boy unless you had an electrical engineering degree or a lab coat. It's not that bad these days. But your other choice is make yourself a pest at a studio and come around until somebody says, "Okay, I'm going to let you do something."

That's what I did.

When you hang around the studio, you watch the dude doing it. And it's only human nature that you get to the point where you figure, "I could do that better." Then you start learning something. Like I tell kids who come in here, they can have like six rings in their nose and a couple of hairpins in their eyebrow and have their forehead sleeved, but I'll look at them and say, "I know your favorite band is Shithook, with the E tuned down to C-sharp, and you don't think you're going to listen to anything else. But if you stay in the music business, one of these days you're going to listen to Buck Owens, and you're going to get it. That will happen. Now if you don't stay in the music business, you can go with what you like when you're young, stick with it, and then quit buying records or whatever you want to do. But if you stay in the music business, you'll eventually get out of your narrow vein of interest and get into a wider vein of interest. You'll go, oh, my Dad used to listen to that, and that's pretty cool. That gives you part of your musical abilities. Everything that you're going to hear will stick with you."

What's your favorite record you haven't done?

Probably [Otis Redding's] Otis Blue. If I could have been involved in something like that. Otis Sings Soul. It got you interested in doing stuff.

You know what, the record that made me want to record things was Remain In Light, Talking Heads.

Ah. That was a pretty-well put together record. They had some pretty high-powered help on that record. They generated interest and got people to help them with their songs. When it comes to that, I move up a notch in to the '70s. I think The Hollies "Long Cool Woman in a Black Dress" album, then you move on up into the late '70s, Sex Pistols, move on up into the '80s, I'm a pretty big Nick Lowe fan. I like Nick Lowe's records and everything he ever did. From a record standpoint, dealing with bands that I deal with and will hold up... Appetite for Destruction. "You want to play guitars and drums and sound like a rock 'n' roll band? Let's listen to that. You'll be happy if you sound like that, wouldn't you?" The Beatles' BBC Series. I didn't record that, but it was recorded by a bunch of gentlemen in white lab coats at the BBC who recorded The Beatles as they played concerts at various locales around the United Kingdom between '62 and '64. The Beatles were on the floor, the people were on stage and it was recorded meticulously, with no overdubs live to 2-track to some lorry out there. They were unbelievably good, based on six nights per week for two years. There are a lot of things. It's hard to pinpoint one thing. You can get a lot of stuff.

I want to ask you ten questions. Simple answers:

Favorite record you've ever done?

Holy cow, there's a handful. God, I don't know if I can. I have a very warm place in my heart for the first Del-Lord's record, Frontier Days. It was my first shot at getting to do something in the big time. I really like The Skeletons record [Waiting] we did for Alias Records. I really like Roscoe's Gang.

Of all the artists, who was the most fun to record?

I always enjoyed recording Joe Terry, Lloyd Hicks, Donnie Thompson, and myself on bass, with some other people coming in and out. Those records were always very satisfying because those guys are defenders of the song. They hear a song, they listen to it, and what they play has no "look-at-me" stuff. It's all in service to the song. When you have people with that mindset, things start happening. To feel that groove and watch that process go was great.

What was a mistake that turned out to be better than what you expected?

I've turned down some offers to do things, but that's a bad mistake. A good mistake? Deciding to get into this! Coming to Springfield, Missouri. Back in Tennessee, there were some good players and some tiny recording studios, but there was no real scene of people writing songs. I got in with people on the professional end of this deal who were happening, and I became acquainted with people who were capable of moving to the next level. I became a better person for that. And meeting my wife!

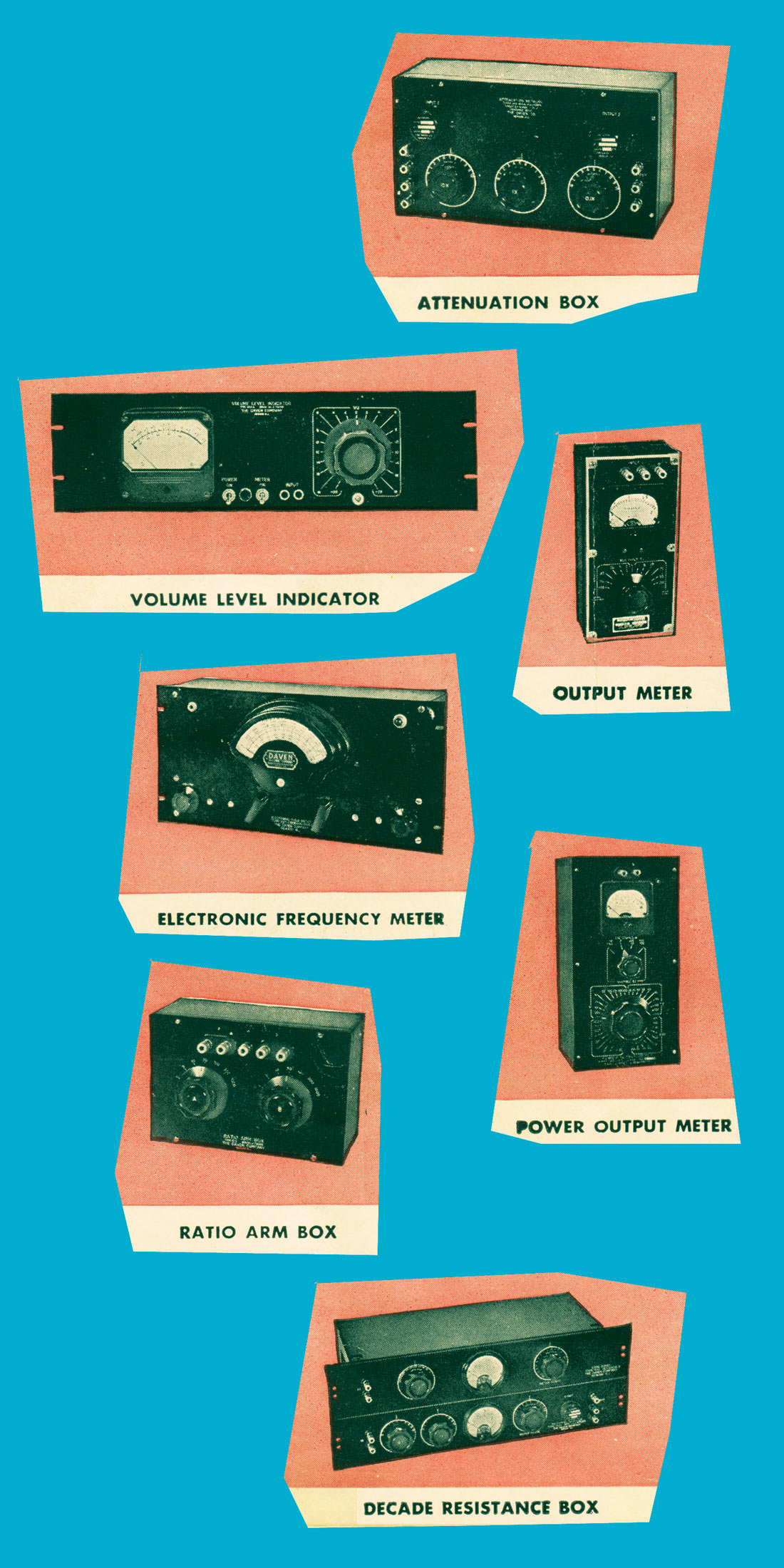

What's your favorite piece of gear that you own?

The [URIE] 1176LN. I've still got it. That's it.

What's your favorite instrument you've ever played?

I'm a bass player, but I'm still a folk singer at heart. I can take my guitar, get out on the sidewalk, open up the case, put on a bad hat, and I'll get people to throw money in the case. "Can you still do it when you turn off the electricity?" I'm a guy who plays bass, not a bass player. I'm a folk musician, and I know a bunch of songs, and if I had to, I could get money for lunch playing guitar if the electricity went off.

What is the best song you ever wrote, and have you recorded it?

I'm trying to think of what songs I like to do when I play in a band. I'll hearken back to some of the first songs I've ever learned. "Pills." I did a song called "I'm Waiting for a Slow Dance," an R&B type thing.

I love that song. You guys did it in The Skeletons.

"Country Boys Don't Cry" is a pretty good song, I think. It's a country song, a walking-bass, Ray Price type song. "Trans Am" is always a favorite. I like it. It's a car song. It's all derivative stuff. "Thirty Days in the Workhouse" is probably my favorite song. Two chords. Do you know the story behind that song?

Not really.

Do you want to hear it?

Yeah, I'd love to hear it.

I was a kid in high school in Erwin, Tennessee, down on the Nolichucky River in the summertime, floating on inner tubes as far as we go. Clinchfield Railroad ran through Irwin and had their headquarters and main yards there, so there was a lot of hobo activity, and there was a junkyard close to the river. There was an area there that was really nice, a flat bank, where people would get some seats out of the cars. There was a guy named Bill, a WW2 veteran. He had a plate in his head and had been wounded. He'd got a couple silver stars and a bronze star with a cluster. He was a real war hero, but he came home fucked up. He would clean the poolroom where we'd always shoot pool, and he'd sleep in the poolroom. In the summertime, he'd go down to the river and hang out. Bill was always around. He was a really nice guy who came from a good family. Bill didn't show up one time for about a month. We were down there every day, and it was like, "What happened to Bill?" Then finally Bill came back, and I asked him where he'd been and if he was okay. He said, "Oh yeah, I was down on Union Street and they had an outside produce thing. I grabbed an apple and ate it and got arrested, and they put me in jail for 30 days." I said, "I hate to hear that." He goes, "Oh, that's all right. If I'd have been a black man, they'd have given me 30 years." Boom. I'm going, "Okay, I get that." He says, "I don't understand the big deal! I mean, they grow on trees!" You understand what I'm talking about? Boom. He spent 30 days in the workhouse, but that stuck with me.

The word "producer" started from the guy who had to produce the master. He was the guy who had to deliver a record to the label.

By definition, a record label would sign an artist, an A&R department would take the reins on it, and then they'd find a producer who would be simpatico to the artist. Then the producer would meet with the artist, help them pick the material with the A&R department and marketing people, rehearse the songs, pick out the people who were going to do the recording and find a studio, and pick out the engineer. Then they'd be responsible to make sure everything came in on time, on budget, as well as keep track of all the credits of who did what. The term "producer" now could be anything from a high school buddy who loans you $300, to a guy who tells everybody what note to play, to anything in between.

I was part of the committee for the Grammy's Best Engineered Album. On a big-time, major label rap album, there were 23 producers on one song.

That's almost like a Nashville song that took 23 guys to write it. In that case, the guy who's really important is the one who said, "We're done."

There are a lot of people learning how this business works. Even people like you and I are still learning how this business works.

I learn stuff every day.

What would be the first piece of advice?

Have somebody around that you can bounce stuff off of who knows what they're doing, knows you, and knows what you're looking for, as well as someone who has been around long enough. Someone who will tell you the truth and won't bullshit you. Most of my work is still with emerging local bands, or local artists. I don't get as many out of town people as I used to, but I'm 70 years old.

_display_hires.jpg)

_display_horizontal.jpg)