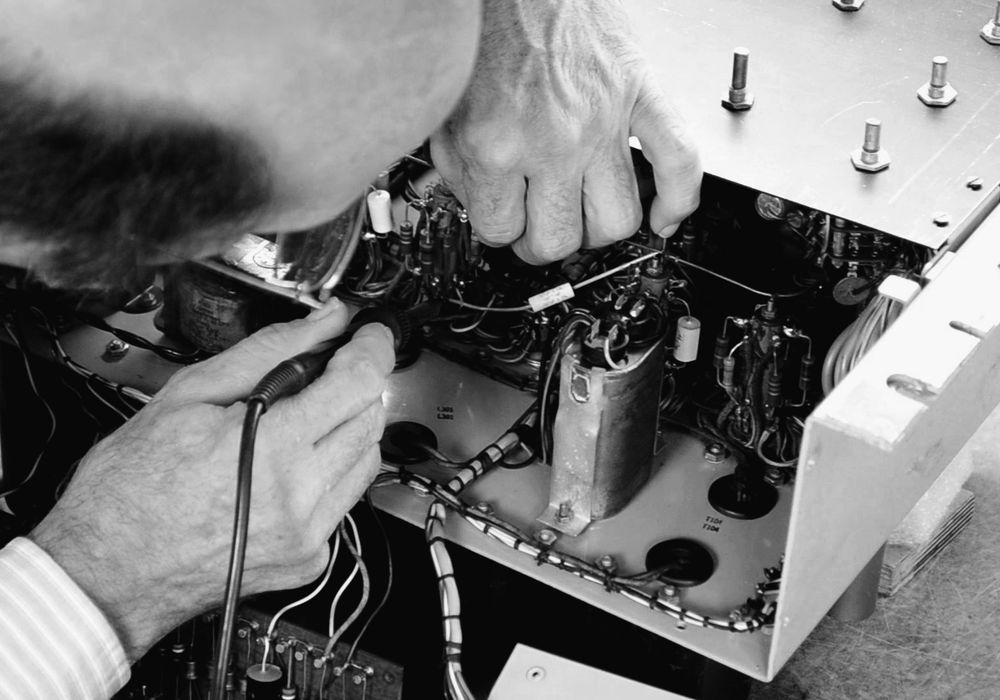

A while back I was working on a restoration process for an album that was long out of print. The only materials I had to work from were a ridiculously scratched vinyl LP and some 7-inch reference reels from the original session. When I played back the reels, I was horrified by the obvious pitch fluctuations on the tapes — it was enough to make me queasy. I recalled that I'd met Jamie Howarth, of Plangent Processes, some time before; given a basic understanding of his revolutionary technique, I assumed he could fix my problem. It worked. The process basically uses recovery of the bias tone off analog recordings to "realign" the audio to the state it was in while being tracked or mixed. Jamie's Plangent Process has helped restore recordings of Woody Guthrie, the Grateful Dead, and Neil Young, as well as solving many film audio problems. I had to learn more about this, and wanted others to know that this service is available, so I tracked down Jamie and picked his brain.

Plangent Processes:

I guess everybody by now probably knows how our process works — it's a wide-band head, wide-band preamp, custom-made stuff that we're more than happy to sell, which tracks the bias on the tape, which is 150,000 cycles per second. Usually it was recorded with an oscillator that is way more stable than the transport was. When you get into the quartz oscillators that you see in the MCI, Studer, and later decks, it's pretty awesome how stable they are and how much worse the transport is. I don't think that people realized how much residual wow we were sensitive to. You go back and listen to these things, and it's actually pretty remarkable when one of them has been de-wowed/de-fluttered how much was actually there that we were willing to accept, and how much that we thought was inaudible. The history of audio is filled with things that were thought to be inaudible.

Early Digital Audio:

I remember Jim Keltner told me a great story about how he didn't like the way that the cymbals sounded, but the groove was tighter. I was like, "How could you assert that the groove was tighter in the difference between analog and digital?" Of course, he's listening in the time domain, while most of us are listening in the frequency/pitch domain. We went back and looked at the timing differentials of these machines, and they're actually throwing a tenth of a percent wow, which is considered to be a little bit high, but acceptable for most of the time and most of what these things were doing. Whether that was the spec or not, that was what most of these things were achieving. I did the math to see if a tenth of a percent of wow at a particular slow speed would drift that much, and it does. Keltner was absolutely right. It wasn't surprising that a lot of guys were hearing artifacts in different ways.

Transport Problems:

The thing that's really been the hardest sell is that you can use our process for triage — for stuff that's stretched or where the machine is in trouble — but listen to what it does on a well-made, hi-fi recording from the '60s or the '70s in terms of clearing out all the debris that was caused by the transport. Listen to how much better and fresher the imaging is, how much more depth there is. One of the things that we heard from one of the more famous producers in the world was, "My reverb tails are longer, and that's what it sounded like in the control room. I've never heard that off tape."

Reframing History:

It's not because we're changing the work or we claim that we're better than Bill Putnam. There are millions of guys out here that are way smarter than I am. But we did find one stupid pet trick that could be done that really does make a lot of difference! The thing that it does is that it does unmoor the historicity of it, if you will. Not the historic nature, because the historic nature is in the performance, but the antiqueness of it. If I want to hear a Sinatra playback, I want to hear Sinatra. I don't think that Rosemary Clooney in 1956 when she sang the stuff that she did, some of which sounds like it's got some fairly decent honk on it, is going to say, "Wait a minute, that doesn't sound like my voice because it doesn't have honk on it." They were killing themselves trying to make the transfer function as flat and as clear as possible.

_disp_horizontal_bw.jpg)