We interviewed Phill Brown in issue number 12 of Tape Op. Over the years he's worked with some of the greatest artists ever, like Jimi Hendrix, Joe Cocker, Traffic, Spooky Tooth, Jeff Beck, Led Zeppelin, Robert Palmer, Bob Marley, Steve Winwood, Harry Nilsson, Roxy Music, Stomu Yamash’ta, John Martyn, Little Feat, Atomic Rooster, and Talk Talk. This is an excerpt from his (as yet) unpublished book, Are We Still Rolling?, and we'll be running more chapters from it in upcoming issues. Last issue: Phill began working at Basing Street Studios and worked with Led Zeppelin, Mott the Hoople and more... –LC

I had worked for the Wailers on two occasions before mixing the album -Live at the Lyceum. The first time was in the Spring/Summer of 1972, just after getting married, and before Murray Head’s Nigel Lived album. I mixed a few songs for the Catch A Fire album. Later, in February 1973, the Wailers were back in England with ten tracks that needed finishing off for their second album to be released in the UK. There were a few overdubs to do and then the mix. Tony Platt and I were both working on the project in Studio 2 at Basing Street - he would do a few days, maybe a week, and then I would take over.

I was 22 years old and very white. It would take a while for me to be accepted by these guys, who were mainly older than me by about six years, except for Earl Wilberforce Lindo, the new keyboard player, who was only 20. The Wailers were a heavyweight bunch of characters, obviously street-wise and at first a little intimidating. The band included Carlton Barrett - drums, Aston Barrett - bass, and Earl Lindo - keyboards. Bunny Livingston, Peter McIntosh and Bob Marley all played guitars and sang. They were all dressed in worn-looking jeans and several layers of coloured T-shirts with jackets and boots. They displayed varying lengths of dreadlocks, and some occasionally wore a woolen hat. With the combination of their stance, clothes, hair and attitude, they gave the impression of being tough guys who meant business. However, there was a very mellow side to their character and for the majority of the time I found them easy to work with. While the assistant Dave Hutchin and I set up microphones, they moved around the studio slowly and determinedly, adjusting equipment, making remarks to each other, smoking and laughing.

Like me, Chris Blackwell was white but at least he was Jamaican, and could speak the patois. I missed or misunderstood a lot of what the band were saying during the recordings - also, having the boss there gave the sessions an edge.

The Wailers smoked grass all day long. This was nothing new, but these joints were big, coned and dangerous - anything from seven to fifteen inches of neat grass. Steve Smith (Island’s House Producer) had referred to the larger ones as ‘baseball bats’. “They take offense if you don’t smoke with them”, he had once said on returning from Jamaica,”and I remember the day someone showed up at the front door with four 55 gallon drums, huge fucking things, and said, ‘I’m supposed to deliver this’. I said, ‘Well, what is it? - I’m not sure I want it’. This guy says, ‘It’s sea water, straight out of Kingston harbour’. I said, ‘I don’t think I want that’, and he says, ‘No, no - it’s for the Wailers. They can’t wash their hair unless it’s out of Kingston harbour - got to be sea water, it’s religious’. I said, ‘Great, bring it on in’. The Wailers are a mad bunch of fuckers”.

It was rumored that Bob Marley’s personal roadie had a bedsit in Earl’s Court, London, where they stashed large amounts of marijuana. No one actually lived there, it was just safer not to carry that amount of dope around. I had been offered a joint some days earlier by “Family Man” Barrett, felt honored, took a couple of healthy puffs and handed it back. "No man, that’s for you," was the response. I felt it was some kind of rite of passage, to see how the young "white blood clot" could handle it. Being stoned and working was not new to the Island staff, and I got on with what I was doing, although it was what we would have called "serious shit".

We were now working on "I Shot the Sheriff". It was necessary to do an edit on the l6-track master - before the second drum fill and the hook "I shot the Sheriff" - to use the start of one take and the remainder of another. This needed to be done before we could continue with overdubs. I enjoyed editing 1/4" tape, but 15 ips/2 inch multi-track editing had built-in problems. Working on a master that had taken many hours to record meant particular care and attention had to be given. It was always easier if the control room was empty of people during these operations and I asked Chris to give me ten minutes. They all went out to the games room or to the canteen so I could be left to concentrate. As they filed out of control room two, I was handed half a coned joint by one of the band. "Hey, you'll be needing this", he said, and with that I was left to it.

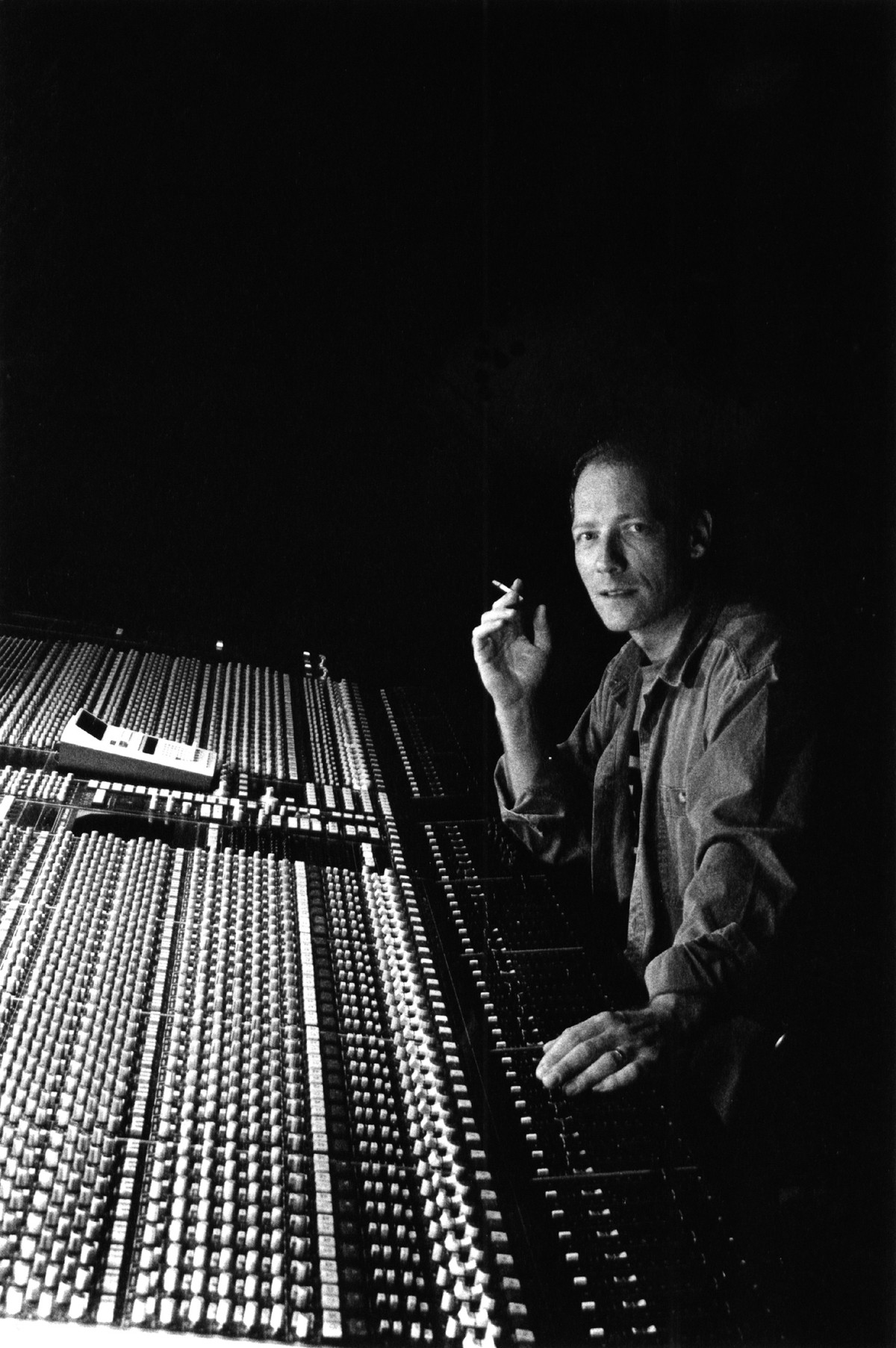

The first edit went okay and I moved on to finding part two. Having marked it with a white Chinagraph pencil, I laid out the tape in the Editall editing block. The joint was in my mouth. Suddenly a small explosion (probably caused by popping seeds) took off the end of the joint. I watched in horror as the glowing debris coasted down towards the editing block in slow motion. Even before it touched the tape I could tell we had a major problem. The tape op, Dave, looked at me with disbelief.

A section of the master tape had melted, its width reduced from 2 inches to about 1/2 inch. I had lost at least a 3 inch length of the section I was cutting to. I felt panic, and was suddenly very stoned. What to do? I needed about a bar of music — the damn fill - from somewhere to replace the one I had just destroyed!

Fortunately there were three takes of this song on multi-track tape, and we were using different sections from different versions. I played some of the sections we were not using and found a similar bar. Someone put their head round the control room door and asked how we were doing. "Yes, a bit of a tricky one. Give me five minutes", I managed to mumble, with my head bent low over the editing block.

As I worked feverishly I tried not to think about what might happen if I failed to repair the damaged master. Some years later an assistant at a studio in New York ended his career with just one mistake. He was working on the album Aja by Steely Dan. After two years of recording, overdubbing and re-recording songs, they were finally mixing their chosen tracks. Many of the master reels looked similar and it was later believed that a tape had been put back in the wrong box, with the consequence that unfortunately, instead of lining up [calibrating] the 2" tape machine with blank tape from the "tones" reel, he mistakenly used one of the final master reels. Not realizing what he had done, he replaced the tape in its box. It was only when repeated searches for the required song had been carried out that this tape was finally loaded onto the multi-track machine and played from the top. Frequency tones filled the first four and a half minutes of the tape. Then, just as they were about to give up and move to another reel, the last few seconds of the song they were searching for suddenly burst onto the monitors. As Walter Becker described to me at Park Gates Studios in 1984, "Man, it was crazy. Don [Donald Fagen] and I were trying to lynch the guy. He was only saved when the studio manager sacked him on the spot and escorted him from the studio - and he never worked in the music business again. Man, we wanted to kill him."

It took about 10 minutes to complete the repair and then there was still edit number three to do. In all, the editing for which I had said, "Give me 10 minutes" took about 30. I called Chris in to listen. The band followed him into the control room. I played the track and waited nervously for the verdict.

“Yeah, sounds fine”, said Chris, “Now lets get on with some Hammond.” Needless to say, since that evening I have never allowed myself or any assistant to change a tape, or to get within six feet of, any tape box while smoking... anything.

Dave, the tape op, was cool and neither of us said a word about the near-disaster. We continued with overdubs and then mixed the album, speeding up some of the songs to make them more acceptable to a British audience. (Article in November 1975 by lan MacDonald - reviewing the band Burning Spear and their album Marcus Garvey: “And just how long is it that the British consumer has been offered a palatable expurgation of Reggae for tender ears and itchy wallets. Didn’t Bob Marley himself allude to the speeding up of the master of ‘I Shot the Sheriff’ for inclusion in his 1973 album?”)

Some months later the Wailers’ finished album was released. It was called Burnin’.