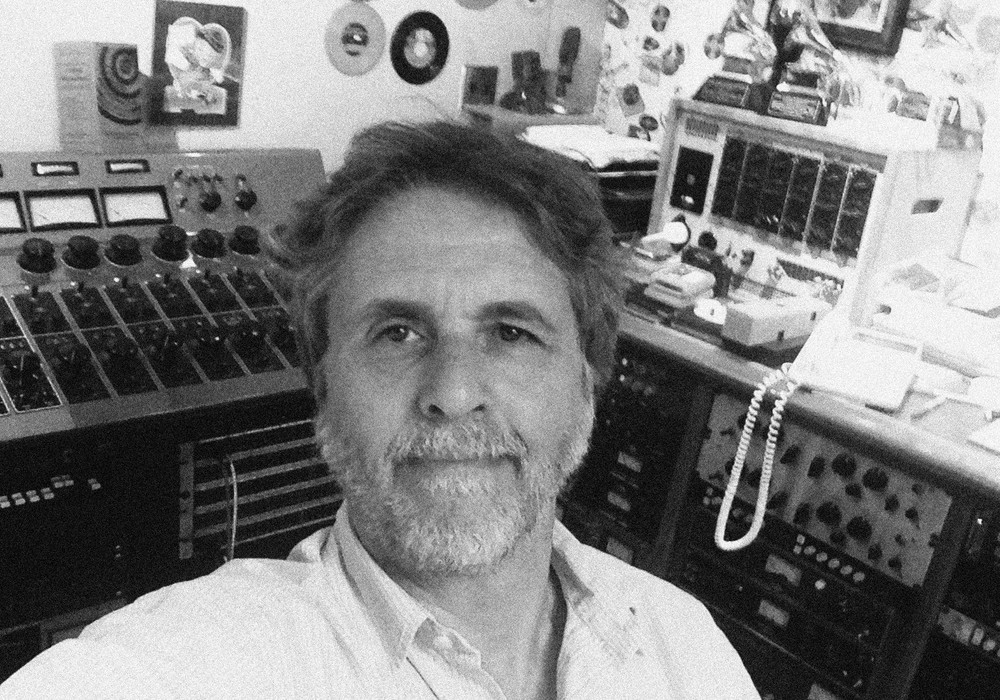

Ocean Way Recording began in a garage in Santa Monica, California, in 1968, as a place to showcase owner Allen Side's custom monitors. From these humble beginnings the empire expanded to include partnering with Bill Putnam and acquiring his United Recording Studio in Hollywood, and building state of the art recording facilities in Nashville, St. Barths, and nearby Sherman Oaks. The Ocean Way "brand" also includes Allen's high-end (and excellent sounding) monitors, a unique and affordable microphone, excellent UAD plug-ins, drum samples, and even an iPad/iPhone app. Allen is also well known for being a meticulous engineer/producer, having worked with such artists as Phil Collins, Green Day, Eric Clapton, Faith Hill, Wynonna Judd, Beck, Mary J. Blige, Ry Cooder, Joni Mitchell, Frank Sinatra, Ray Charles, John Williams, Jerry Goldsmith, André Previn, Michael Jackson, and Frank Zappa. He's also well known for leading the charge on reclaiming classic tube mics and gear that was being abandoned in the '80s; he has probably listened to, and evaluated, more microphones than most of us ever will. Not long ago Allen sold Ocean Way Recording in Hollywood, where we met for this interview, and it has now reverted back to the original United Recording name.

What do you think about the whole PONO movement and things like that?

I think anything that gets us in the direction of slightly better audio, I'm there. I think we're seeing a lot of people who like vinyl, but if you have high-res digital that gets directly cut to disc, it's way better than 44.1/16-bit, as long as it's the first three cuts or so. If the first three cuts of the LP are cut from the master, it's pretty damn good, no question about it. Phil Ramone was staying with me one time at our house in Georgia, and we had this long discussion about what this is. From his standpoint, whenever he put his name on a record, the one thing that he insisted on was that it was mastered from the original 30 ips, 2-track tape and went straight to the cutter. Of course, you can get about 50,000 copies out of one set of lacquers, so you've got to do quite a few transfers. The problem he had with Billy Joel records selling 14 million records, you had to make a lot of lacquers, so he became a little concerned about wearing out the master tape. The difference between coming off of tape and coming off a copy then was night and day. A 15 ips, Dolby copy was like losing 35% of your sound.

People growing up now would not even realize that we had no option. Copies had to be on tape.

It came from the master and went right to the disc. It sounded amazing. When you play the lacquers, the lacquers were like steel. Forget about the pressings. When you played the lacquers and compared them to the master tape, it was amazing how good it was. There was a lot of concern about quality then. Even when you listen to '80s rock on the radio, it's so much punchier and sounds so much better than the current stuff in the alternative rock scene.

I think it leaves a bit of dynamics within the mastering.

Exactly.

It all comes down to the original recordings too.

Absolutely.

I feel like sometimes lately people don't understand that. They want to move fast.

They're recording while listening to multiple plug-ins. They don't even know what they're recording, because they don't know what the source actually sounds like. I see this all the time. Or, as a mixer, stuff comes in to me with all these plug-ins. I listen to it, and the first thing I do is turn everything off. I'll listen to it first, and then I'll finesse. When you finally bring it up on a real console where you can use analog EQs and good reverbs, it's all of a sudden like a different world. The toughest problem is people who compress everything while they're recording. It's one thing to compress with a plug-in, but if you have the original source uncompressed, at least I can deal with that. But once you destroy it, you can't really get it back. It's gone. I'm a bass player, and I record Nathan East or Rickey Minor, and I don't need any compressors. Their tone is perfectly balanced. I don't need compression for anything. But maybe I'm working with a bass player in a band who's all over the map, so I need to get things slightly in control. I only need enough so that I fill the holes and things sound good — I still have some dynamics. The other thing that I do is take a mult of the bass, compress the mult, and combine them together. Then I get all the sustain and all the attack.

There's a lot of tricks to making things still breathe.

I was doing an album with Faith Hill at our studios in Nashville. We had a big orchestra with a fantastic rhythm section. David Campbell had done the arrangements. We were doing these songs, and Faith is there with the producers. We're recording stuff, and it sounds punchy as shit. It's really dynamic and really fun. Then there's this one song that they had already recorded, which we were going to overdub the orchestra on. We put this song up and play it. The front sounds okay, but all of a sudden the chorus comes, and the orchestra was soaring, but the track never left the gate. Faith asked me why it sounded like that, why it didn't have any impact and sounded so small. The engineer who had done it was sitting right there. In Nashville, they're really into compressing everything. But then you talk to a mixer like Chris Lord-Alge. He mixes a lot of country stuff. He'll do what he needs to do, but if you give it to him that way, he has nothing left to work with.

That happens a lot down the chain now. Mastering engineers say the same thing.

"They've ruined it before I get it." The biggest problem is that a lot of guys who are pretty good at Pro Tools, and also pretty musically-inclined, haven't got a clue about dynamic range or the gain structure of a mic pre when they're recording a vocal. They don't even know how to turn off the compressors and set the gain, figure out perfect positioning, and then look at the compressor and see where that needs to be. They start from the wrong place. The ratios are set wrong, the gain's not right, they start hitting reds and it's all distorted.

The bar's been lowered.

I've known Bernie Grundman for 25 years. Every once in a while he would call me and have me listen to something by Bruce Swedien that was just unbelievable. I haven't gotten a call in 15 years.

You have many things on your plate. Do you have more time now?

I started playing guitar again, acoustic guitar. I write a lot of pretty complex melodic stuff. I'm just loving that. My buddy, Steve Vai, is my critic. Steve and his wife lived next door to us, and his kids and my kids grew up together. We had a door between the properties. We see them all the time.

He did the Ocean Way Microphone Locker app too.

We had done that a long time ago for CD-ROM. It was very well-received for what it was at the time, because you could actually hear eight different microphones on one instrument at the same time. No one had ever done that before. Of course, it took up so much space at that time to be able to actually do that. We did most samples in mono. People liked it so much. It was pretty successful. All the music schools bought it. Steve loved that one and kept asking if we could re-release it. He re-did it and put it together and put it out. It's been reasonably successful, because it does provide information that you can't get. I'd love to re-do it now. Every one in stereo.

There are some incomplete sections, too.

I know. At the time, you just had a limited amount of space.

I hadn't even thought of that.

Now, it's like nothing. On the old one, the time it took from sample to sample was much longer. Now you can just knock them out. Back then you had to wait a while in between. When I was doing some of the albums, I used to do a lot of audiophile records. I'd do direct-to-disc, or live to 2-track and just do the whole thing live. There was a Soundstream machine that Tom Stockham invented. Honeywell Digital Transport, recorded at 50 kHz, 16-bit. It sounded really good, but you couldn't punch-in. All you could do was record complete takes. I did a couple Tom Scott records where we did like Jerry Hey and the Horn Mafia, Vinnie playing drums, three percussionists, three guitar players, background singers, all live to two track. It sounded great, because it was one generation. I did direct-to-disc where we basically had to do five songs in a row without stopping. Once the cutter comes down in between the songs, you pull the master down and make all your changes and push the master up, and you have whatever time it is between the two cuts. By the time you're on the third or fourth song, if anybody makes a mistake, the whole side's ruined. Or, if you as an engineer accidentally hit something too hard and it pops, the whole side's ruined. There's tension. But coming from film when I used to work at Fox, and we were doing motion pictures and scores, most of it was direct to six track or three track mag, not even multitrack involved. We'd do multiple takes, and that was it. The mixes were live.

You've seen how huge film mixing is now, how many tracks and stems.

Oh yeah. It's kind of crazy. Of course, when you're working with Jerry Goldsmith or John Williams and stuff, generally speaking, the stems weren't even an issue. On the pop scores now, the director wants a woodwind stem, a brass stem, all these things. You're using M 50s overall anyway, and there really isn't a stem that lays in where you want it to be. It's not really separate. It's in context with the overall thing. What we end up giving now is an orchestra stem, an overall mix of what it is, and then if there are instruments recorded solo, we have a stereo mix of five separate elements, synth groups that are particular or drum machines, those you give separate stems, but it all balances out as a pre-mix and lays out as a six track. Then we send it to them.

That's crazy.

We had this one at Record One as a 96. We mixed Avatar and a lot of other big movies, but the film business began to shift and move farther and farther to England and Czechoslovakia, Prague. That was a lucrative business for a period of time.

You're an important figure in the history of studios, so it's nice to get something in Tape Op.

Good. It's fun, sometimes you pass along things about how to get the most out of Pro Tools sessions and how to get the most out of visual recording, how to maximize your bits and resolutions. All of those things make such a difference in your product.

You've mentioned a lot of scenarios where there's a lot of pressure and things have to be done on-the-fly. Have you thrived with that over the years?

I get used to it. With Rickey when we're tracking and stuff, or working with Rob Cavallo all those years on the Goo Goo Dolls and Green Day, he has minimal patience and wants things quickly. He's very talented and moves very quickly. I'm used to making it sound like that immediately. I don't even get sounds really. When we were ready to track, I'd done everything before he walked in the door. The drummer hadn't even sat down the drums, and I had every level within a millimeter of where it's supposed to be, everything's EQ'd, verbs are set. I was doing a tracking date one time some years back with Phil Collins. We had some pre-records and overdubs, and he was going to lay down drums over top of stuff. I had everything set up, and when Phil walked in, I had already gone out with the headphones, sat in Phil's position, and played the drums. I knew exactly what it was going to sound like when he sat down to play. When he sat down to play, he put in one pass and he was done. Musicians love to hear it like that. I had just the right amount of bass, everything was great. I go and make an effort.

You've got to spend a lot of time planning and preparing.

Also, sometimes even in situations where I did that I really needed more rehearsal time than there was. We're working upstairs in the control room with Pro Control system. That's all they had. I pick all the mics, get everything set up, get it going right, but we don't get the kind of rehearsal I want to get. They're trying to get shots of the video, because they've got one shot to get all the cameras, and it's an eight camera shoot, doing it all simultaneously. I didn't get all the lines perfect until we pulled up the fader to start the session. I'm used to mixing live. You've got to make it sound good right away. You just work it in and start finessing it. By the time you hit the second or third song, you're pretty good.

One hopes.

One time I was doing a show with Ron Isley and Burt Bacharach. It was for Dreamworks. It was a very nice record. We were going to do a big showcase at a theater in town. Burt said to me to find a place I thought would work. I ended up picking the Wilshire Theater. I liked it much better than the one down the street. It's a little on the live side, but when the audience gets in, it's not bad. It was a union house. I brought the PA system and everything else. We were going to have four background singers, he's singing live, and Burt's playing piano, there's a full rhythm section, brass, strings, everything live. Everybody in the world I knew in the record business was there for this thing. Also, when I do a PA like that, I like for it to sound like a finished record. When I do a PA, it sounds high-fi. We get this thing going, and the only thing I was using were their lines between the console and everything else. Half of the lines didn't work. It was the day of the session. I had the rehearsal coming up, and I hoped to have a nice rehearsal to get everything balanced. But half the mic lines weren't working. So the rehearsal starts, and I have maybe 13 lines working. I'm working the whole rehearsal just trying to get mic lines up and going. By the end of the rehearsal, I'm still probably a dozen lines short of having it work. The rehearsal went by, but I'd done nothing other than get a few levels. I said okay, I've got two hours before show time, so I can get it fixed by then. I was running extra lines. Then the lights go off and the union said everybody had to leave the hall, they were having a union break, and no one could work until thirty minutes before the show. So I'm working like a dog, running lines from the console myself. Burt walks on the stage, and I've got the last mic working when they walked on stage. Then Burt says to the audience that he wanted to thank me for being there, and I'm sitting there, and everybody I know in the record business was sitting in the room. It was unbelievably painful, but it came out great. Once everything was working, once I've got it all, it's really not a problem.