We first met esteemed mix engineer Michael Brauer in Tape Op #37 in 2003, when Mike Caffrey interviewed him about his multi-bus mixing technique. Some 16 years later Michael and I sat down at his new space, BrauerSound Studios, to discuss his career path and unique mixing techniques. He's crossed genres frequently, working as a mixer on projects by artists as varied as Luther Vandross, Aretha Franklin, the Rolling Stones, Tony Bennett, Coldplay, John Mayer, Calle 13, Angelique Kidjo, Phoenix, Bon Jovi, M. Ward, Grandaddy [Tape Op #7], Caveman, James Bay, and Grizzly Bear.

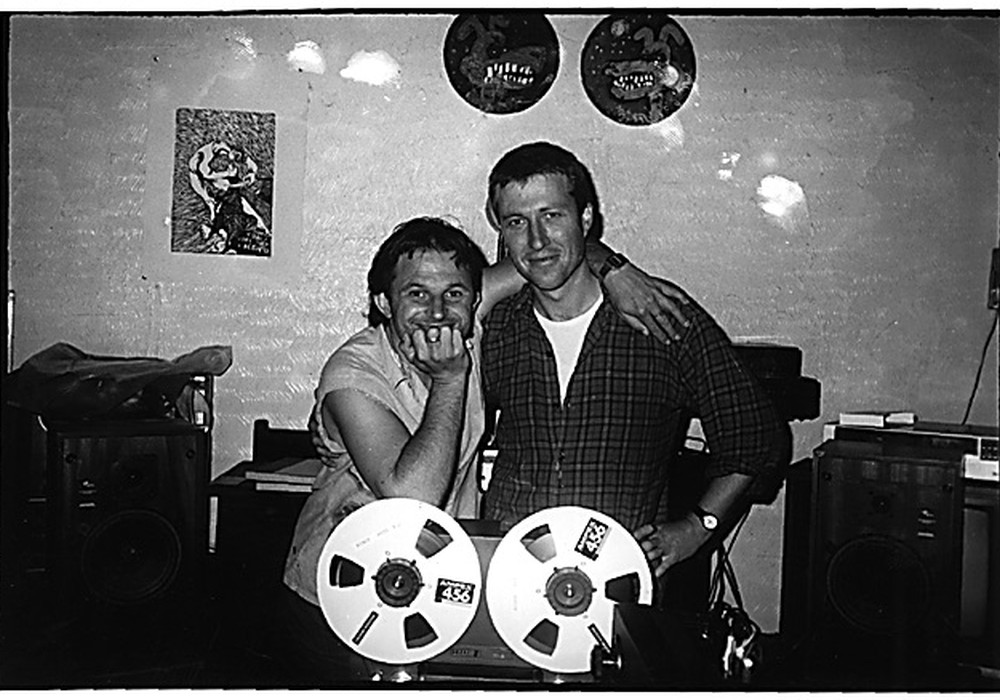

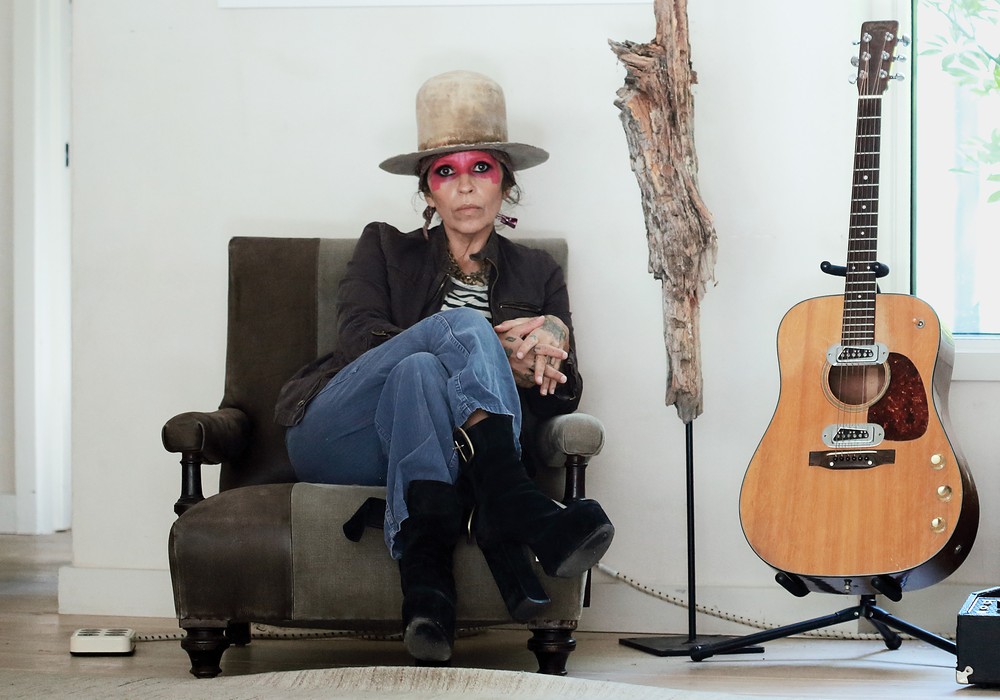

All archive photos and captions courtesy of MB.

I realized that I've never known how you got your start in this business.

The start is always because of one particular record. Until then, you're just slaving away. Suddenly, one day a record comes out and you become successful, and people say, "Who is that?" For me it was kind of a slow ramp. I was at MediaSound; I got hired there in '76. I went from intern to head of the interns in the shipping department, and then assistant, within a year. Then I was staff engineer within two years. Back then, it really wasn't a stretch. You could become a staff engineer in a studio that had three rooms, with six or seven senior engineers. They had senior engineers and assistants, and eventually the assistants would move up into the engineering positions. That studio was well known for R&B.

Who was managing it back then?

It was managed by Susan Planer, a woman we all loved dearly who passed away. And it was owned by John Roberts, Joel Rosenman, Bob Walters, and Harry Hirsch. John and Joel financed Woodstock. They needed a place to mix the show [movie and album], so they opened this studio called MediaSound.

When I interviewed Tony Bongiovi [Tape Op #127], he talked about mixing it.

Bob Clearmountain [#129, #84] went from intern to assistant engineer right away. He was one of the early ones there to be mixing. It was an incredible group of people. The success rate of the engineers that came out of that studio is really quite impressive. I was doing a lot of records. During the day, we'd be recording commercials. You couldn't make any records during the day, because all the musicians were getting paid double and triple scale [on commercials]. Between nine and five is when we'd be recording and mixing. Two days later, you'd hear it on the radio. From six o'clock to two o'clock, we'd be making records. We'd be doing double shifts, seven days a week. I don't remember what a weekend felt like. It didn't matter. I started late when I got hired there; I was 25. I'd been on the road with a band, and I didn't want that kind of life. I'd been out of college for a couple of years. You learn by starting to do overdubs. I started by recording Sesame Street. You had to start off being able to do Sesame Street, because it was all live; a room of ten musicians going right to 4-track and mono. Everything was done at the same time, and it was done live. That's how you really cut your teeth. Fred Christie was the senior engineer who mentored me and many others. Eventually there was a lot of R&B coming in. I was working with Luther Vandross during the day. He was the top jingle singer at the time. He was doing all the main ads; McDonalds, Coca-Cola, you name it. He was the lead on that.

He could just nail it?

He was beyond belief. There was the same group of background singers for all these dates. You saw them day and night. Same with these musicians. You'd see Will Lee in the day and again at night. You'd see Paul Shaffer, Allan Schwartzberg, and Bob Babbitt when he moved from Motown. Great musicians. The list goes on and on. I think I was one of the first to record Marcus Miller at Media when he was first breaking out. And great, great arrangers. It was just a wealth of beautiful, great music. We were doing record after record, day-in-day-out. It was mostly R&B. Van McCoy was there for a time. Fatback Band. Tony Bongiovi was doing all the big Motown and funk. Then one day this Italian producer, [Jacques] Fred Petrus, was producing this new act in the studio. It was just a band; they didn't have a name. If they became successful, then they'd put a band together. They were at Power Station, and they were having a tough time getting the right mix and couldn't find the right vocalist either. Yvonne Lewis, the vocal contractor there was a good friend of mine, because...