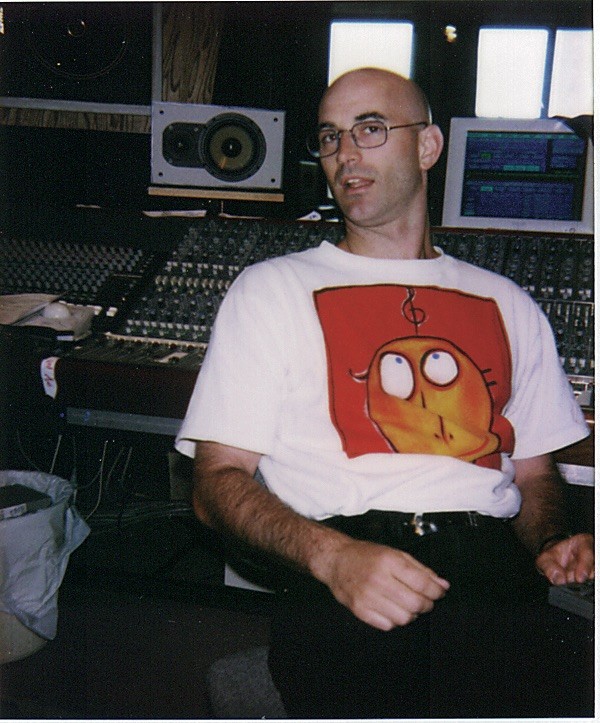

At any given instance in time, David Bottrill partakes in one of three activities. He is either submerged in the realm of slumber, routing signals on a recording console or is seated in an airplane high above the ground. In fact, he travels so often that the next time you gaze up at the sky and see a plane scrawl across it, he just might very well be inside it. And where would his destination be? A place with a recording studio no doubt. And on an aeroplane, one can sleep.

From an early age the native Canadian found himself in the intimate work habitat of musical vanguards Brian Eno [Tape Op #85] and Daniel Lanois [Tape Op #37 & #127]. He was not only responsible for skillfully operating world-class equipment, but was also forced to push his own creative envelope. A few short years after his indoctrination into the studio he relocated to Real World studios in the UK, where he worked on such notable albums as Peter Gabriel's So, Passion and Us. Bottrill is renown for being diverse with a forte of applying his techniques to a wide range of artists: liner notes in albums by King Crimson, Clannad, Tool, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and even Kid Rock immortalize his moniker.

His exceptional talents as engineer, producer, programmer and ace of spacious mixing keeps him from staying put musically and geographically, as he constantly shuttles back and forth from his decade- plus home base in the UK to locations across North America and Europe. This is perhaps the reason why his verbiage remains free of infiltration from British colloquialisms. Well, almost. At times he is heard referring to a console as a 'desk'...

The blueprint that depicts Bottrill's entry into the domain of wires and microphones traces back to the dawn of the '80s in Hamilton, Ontario — a modest-sized blue collar Canadian city known for its skyline plumage of industrial smokestacks. "It's a curious story," begins an energetic Bottrill. "I grew up in Dundas [a bedroom community outside of Hamilton] and, like most people, I was unsure what I wanted to do with my life for the most part and tried a lot of different avenues, including going to Mohawk [Community] College for a Business Administration diploma. I never actually finished [the program] because two personal and significant events occured that kind of woke me up to the fact that I wasn't really heading down the right path."

The year was 1983. Bewildered in a premature version of a mid-life crisis, Bottrill decided to seek medicinal refuge in the ever-secure world of music. "I was always a guitar player and in a bedroom-basement band and I was always interested in trying to do something with making music. My girlfriend at the time said her uncle had a recording studio in Hamilton and said to go look if there was something there for me as an opportunity. So I went to Grant Avenue studio and her uncle was Bob Lanois [co-owner and brother of producer/engineer Daniel]. The first time I walked into that studio, having made an appointment, and looked at the control room and spent a little time there I thought, 'Well this is a pretty fantastic thing to do!' They didn't have a job for me at the time but said I could hang out to learn. So I spent the day doing odd jobs — washing windows and so on to make money so I could go in at night and assist at making coffee, sweeping up and eventually I got to plug in microphones."

In a true existential moment that combined both his intrusive enthusiasm and curiosity with the chance element of being in the right place at the right time, Bottrill stepped into a vehicle that would take him on a life long journey. "The first session I was involved in at an assisting capacity was Brian Eno and Dan [Lanois] doing the 'Apollo' soundtrack. That was a major influence in how I was to work ever since." It was no question that at that precise moment Bottrill knew he was on and in the right avenue. Next he participated in many a session "in eclectic-land" by Teenage Head (an infamous local punk band), The Parachute Club, Luba (Secrets and Sins) and yet another Brian Eno soundscape opus, Ambient #4/On Land.

By 1985, Grant Avenue studio had earned the status of fame due to its comfortable atmosphere and the aura left by reputable artists that had channeled their souls onto tape there. That year the brothers Lanois decided to sell the studio, and explored many options including the possibility of dismantling it and selling off the equipment. "We felt it had a heritage and didn't want to see the studio die," he recollects. "We began to rip out and dismantle the board and at the 11th hour Bob Doidge [current owner] came up with the money to buy the entire studio and we spent the whole night plugging it back in. Without any prior experience, what I ended up doing was finding the way the wires had been bent into each connector and tried to line it up again — it was very funny." Having been once again blessed with a continuous electrical current running through its wiring, Grant Avenue ended up...