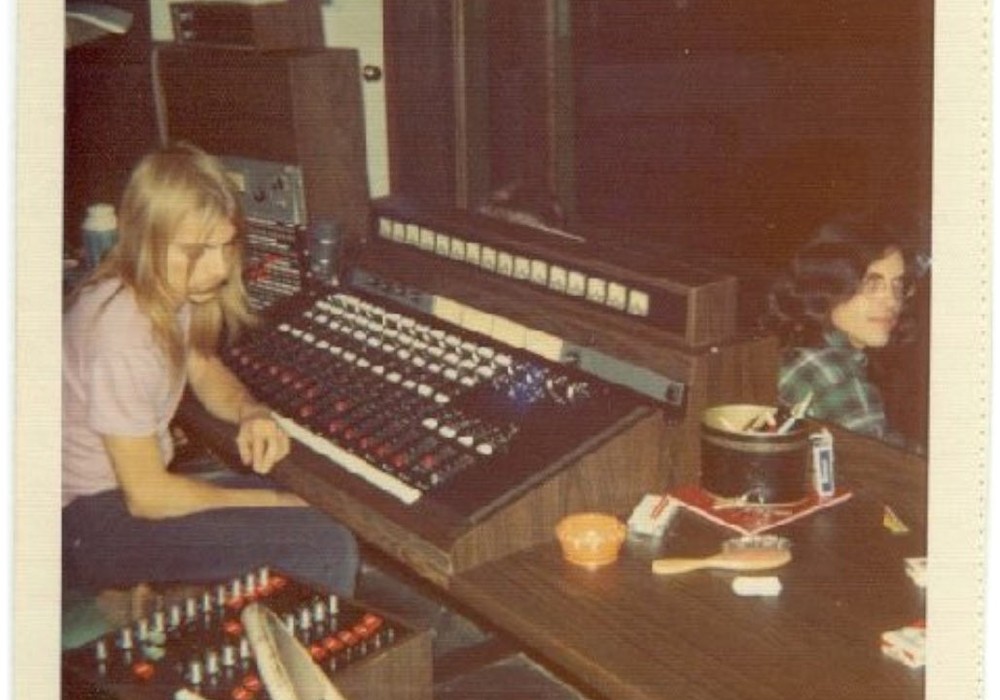

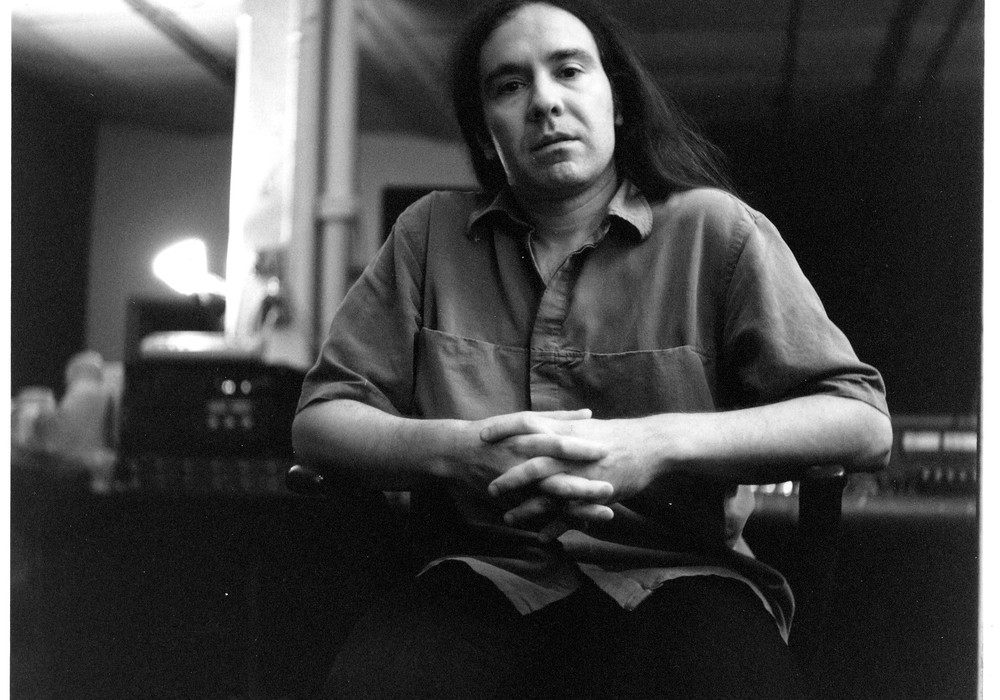

Twelve years later, I recall Mark Rubel's directions to Pogo Studio from our very first conversation. Passing through that red door at 35 East Taylor was more magical than walking into Disneyland back then, and remains so today. If ever a store was an expression of the shopkeeper's personality, this Champaign, Illinois, recording institution is the archetype. Located in an old brick warehouse, Pogo's entryway serves as both isolation booth and scrapbook. The walls are lined with bizarre tabloid photos, wacky electronic toy packages, comic strips, campy band photos and a very significant picture postcard of a horse wearing a propeller beanie and sunglasses. The live room is frequently ringed with clients' instruments, amps, and cabinets, interspersed with studio gear that they'll put on their wish lists. The control room boasts more noisemaking toys, sound sculpture, racks of gear taller than your head, a microphone museum, a completely reconditioned 24-track Studer, a 1971 API/DeMedio recording desk with classic American pop pedigree (originally built for Fantasy Studios to record Creedence Clearwater Revival albums), the requisite big comfy couch, and a fully functional modular Moog system. If you're at all musically afflicted, the place will induce heart palpitations.

At May 2004's TapeOpCon in New Orleans, Rubel used a pair of analogies to describe his quarter century at Pogo. He likened Champaign and its local music scene to a garden which he has helped nurture. He alternately compared himself to the town photographer, documenting successive generations of musical output centered about the University of Illinois.

Fortunately for many, Rubel is also a willing teacher, opening Pogo's doors to Parkland College students yearly, while teaching Introduction to Music Business at Millikin University in Decatur, IL. My own education began by hiring Rubel's services for a project. I caught the recording bug those dozen years ago while tracking my band's first album, and I consider Mark responsible for the knowledge I've gained that wasn't simply the result of learning from my own stupid mistakes.

Pogo has hosted projects for RCA, Capitol, Warner/Reprise, Jive and Sony. Mark's clients have included Alison Krauss, Adrian Belew, Shiner, Jay Bennett [Tape Op #41] of Wilco, Hum (Mark produced Downward is Heavenward with the band), Poster Children, Toby Twining and countless brilliant artists you've never heard. All receive the same good humor and loving attention to detail.

In addition to everything else, Mark is chasing three decades of considerable success as bassist for thrash oldies band Captain Rat and the Blind Rivets. With his spouse Nancy, a fine artist, he's also a tireless laborer on behalf of animal rights. It was a pleasure to climb the mountain and speak with the guru for Tape Op.

With the extreme hours spent running a studio, I wonder how you manage your teaching and performing schedules or pursue social concerns.

It's pretty funny when you're checking in at the Tape Op Conference — everyone's in the lobby checking out each other's studio tan, to see who looks most emaciated and etiolated. If it were a Tae Kwon Do convention, we'd be casually checking out each other's chest development or biceps. Here, it's finding out who has the worst case of scurvy or rickets. No doubt about it, you get cave blindness. What do you do about that? I take walks. Sometimes I don't get outside much.

Pogo seems very much an extension of yourself.

I think that's ideally what a business should be — an extension of the person driving it. It's also an expression of one's philosophy about individualism, which applies not only to how they operate business, but how they approach making music. Many people make a studio a certain way because that's the way they think it's supposed to be. They read as many magazines as they can, and try and get as much gear as everyone else. They try to make it look how their clients think it is supposed to look. Right? So, essentially, they're trying to conform. There are so many studios that are physically impressive. They look like a cross between a space ship and an operating room. They have a black leather couch and so forth. They might be impressive places for a photograph, or they might be impressive to an advertising agency client, but they are mostly not very pleasant or conducive places to make music.

You want a comfortable place, particularly for newcomers who could be intimidated by the environment — someplace that puts them at ease, so they can enjoy themselves, and create.

The same thing goes for people who have been doing it for a long time. The right environment and atmosphere are essential.

Do you think Aerosmith would make a better record at slick studio or at Pogo?

You always have to define better. Would they make a more successful, radio sounding record?

Would they make a record I'd be excited to hear if they came to Pogo?

They'd probably make a record at Pogo that you would like to hear, because we focus on the things that you and I think are more important, which are the performance, the individuality of the players and their instruments, and the integrity of the moment. When I say that there's a drive to conform in people's businesses, you see it in musicians, too. Are they following somebody else's musical direction, because that direction is commercially successful at the time? Are they trying to conform to what they think people want to hear, or what they think record companies want to hear? Or are they trying to realize their own individual personality and creativity?

There's not a Mark Rubel record, and you've got Pogo at your disposal at all times. Did you consciously decide that your own artwork and personal creativity is manifested by guiding and enhancing that of others?

There have been times when I've said I'm going to make my own record, which would be a pretty damn interesting record. But I think that ultimately, everyone is suited best to different kinds of creative work, and I work well collaboratively. Partly, it's just a matter of time. I'm working all the time, helping people make their records, trying to teach people how to record and teaching them about the music industry. I get a lot of my own musical enjoyment from performing in my band. On the rare occasion that I have some time off, I'm probably not inclined to sit in the studio over the console or a musical instrument.

You don't often find yourself thinking, "I've got ten minutes to play piano."

Well, I do sometimes, and it's very therapeutic. It's ironic, because we have so much equipment here, and so many instruments. These days I play the piano mostly. Cumulatively, I probably spend most of my fun time messing around with the Optigan.

That thing is so strange. When did you get that?

It's a funny story. Before I really knew what an Optigan was, my friend, Rick Valentin from Poster Children, told me about it. It was obviously something Pogo had to have, so I put an ad in the local trading paper — "Wanted: Optigan." The ad expired. About a month later, I got a puzzled phone call. "You're looking for an... Optigan?" "Yes." "Well, we have five of them." So I went down to their warehouse. They had five of them in varying states of disrepair. Two of them worked, and I bought all of them for $250.

Was this in Champaign?

The House of Baldwin. It's a piano store. They've been there for a long time, and they have a storage area. The Optigans were all there. There was a brief run on them when it became the home entertainment thing around 1970. Then I think most of them broke. Anyhow, I have two working ones with quite a few extra parts.

It's great that you have room in your building for things like that. Did you have to modify the main floor to get the ceilings as high as they are?

We just had to take out a suspended ceiling. I think they're about 14 feet. I got a Starbird stand the other day. It's a fancy-schmancy, $1000 microphone stand with a very big boom. I could put it at one end of the studio and extend it to the other end. I've been putting mics up by the ceiling, in the unexplored frontier of my acoustic environment. I'm starting to think the ceilings are higher, because this thing has to go way up to get the mics in the corners. They may be more like 16 feet.

You've said before that you especially enjoy capturing sounds and getting the best performances, and that mixing was one of your least favorite things to do. Do you mix more these days?

I am doing more of it, and I think I'm doing it better. I have a feeling that many people spend 30 percent of their time recording, and 70 percent mixing and manipulating. A lot of the records on the radio have 15 percent of time spent recording and 85 percent mixing and manipulating. I'd prefer to see the opposite ratio. If you take the time to get the performance correct, and get the sounds as good as possible, it only takes four minutes to play a four- minute song. I think more people are getting lazy and recording mediocre sounds, taking the approach that they can edit, manipulate, trigger and so forth later. There can be a number of problems with that. One problem, especially when doing sample replacement, is that you end up with things being generic and inherently uninteresting, because you have missed the layers of nuance present in an actual performance. Also, you can give yourself option anxiety and leave too many decisions open until the end. That's something I learned by starting out with a very small amount of equipment and a smaller number of tracks — how to do things economically, how to make confident decisions at an earlier stage. One of the goals is try to build it all into the grooves of the record. Then mixing becomes a polishing or finishing process. I mix quickly. I try to mix more gesturally, and I try to commit to the mixes that I get at the end of sessions. Many times, those end up feeling and sounding better, because there is less second-guessing involved.

There's usually a large amount of time and experience required to achieve something that unforced, though.

I imagine it's this way for somebody who's a professional tennis player. When you first learn tennis, you have to think about where to put your arm, what your form is, where you should be standing and so forth. Eventually, it becomes almost a spinal reaction, where in many ways you have to put your conscious mind aside and just let things happen. You do them by feel. I feel the same way about playing music or recording. A lot of times, I'll make an intellectual decision to use a particular microphone, or instrument, but the evaluation process has become almost instinctive. When I listen, I can tell if it feels right or if it feels wrong. It's one reason I like to have clients there, even when mixing. I use them as a sort of meter. They don't even have to say anything — I just watch them out of the corner of my eye. I watch the angles of their heads and whether they're nodding their heads or how their eyebrows are wiggling. You can tell by their posture whether they're happy or responding.

You can put a wedge of red carpet behind the right side of their heads to see if they're clipping.

[laughs] Here's something else I think is very true: The key to making a good sounding recording often has more to do with arrangement than with recording techniques. Much of the process involves who is going to play what, when, where, in what register, etc. It's one reason why I use a lot of guitars in alternate tunings — Nashville tuned guitars, octave- strung guitars, baritone guitars. I'm trying to shift things out of the vocal spectrum, so there's a place for everything. It's that elusive quality of a great recording, where you can focus on any element and hear everything being played, yet the overall sound is wonderful. It's something that I aspire to. Another instrument that I use a lot is a double-neck six-twelve. We have it wired to do all sorts of interesting tricks, with separate outputs for each neck. Sometimes, we'll play the six-string side and use the twelve-string neck as a sympathetic lead vibrating harp. It's an amazing sound. You can run the six-string through a regular amplifier, and the twelve-string through a Leslie cabinet or a Roland Jazz Chorus or an analog phase shifter or some kind and tremolo amplifier. We've had some fairly complicated rigs where we'll mic the strings of the electric guitar, run the six-string through its own amplifier, run the twelve string resonant neck through some kind of spinning, swirling amplifier, and do a room mic along with that. You end up with quite a few tracks, but it can fill a mix nicely without having to add lots of other instruments. The swirling and the harmonics act as a nice musical glue in the way that a Hammond B3 is often used. I do a fair amount of that kind of sympathetic string recording — put the piano bench on the sustain pedal, then use the piano as a tonal reverb when someone is singing, or playing guitar, or even drumming.

I imagine that could really add texture to spare arrangements.

I use it in rock songs, sometimes. It just depends on the melody and the tempo and so forth. It's something you may only use in certain sections. I also use lots of acoustic filters and resonators and water bottles, boxes and tubes over microphones. I find those to be inherently more interesting and more fun than equalizing or using some kind of plug-in.

It's probably an interesting social experiment to see which of your toys will be picked up and used on the recordings.

Somebody called Pogo a musician's petting zoo. It's wonderful to have all the instruments around, for a number of reasons. One is that it encourages play, a sense of fun, and experimentation. It's just human nature. You'll look around the room, your eyes light on something, and you might decide to try that.

I'd love to play with the Moog, but if I were paying by the hour to learn how to use it, that could be intimidating.

That's why other things that are a little less difficult to figure out often get more use. Also, having so many instruments around, people learn the value of the real thing. They recognize a real grand piano or a real Hammond or a real amplifier and a selection of different snare drums. They've been doing enough home recording, trying models and synthesized versions of things — they're curious to compare.

I'd enjoy having access to Pogo's microphone collection. You just picked up my personal Holy Grail piece — a Neumann SM2. I also heard the lovely piano track you captured with a single KM 256. Is that your favorite for acoustic piano recording?

It is now. I haven't used the SM2 in there, but it will probably be a wonderful thing, too. I actually used U67 on the low end and 256 on the top end for the piano. The 256 is fantastic, especially on my piano, which is a beautiful-sounding instrument, but it's not all that large. So the 67 helps it sound a bit more robust. The 256 is just so sweet and velvety. For certain applications, I haven't heard anything better. For acoustic guitar, for single drum overhead, it's amazing — for drum kit, for percussion, for piano, violin and viola, it is just fantastic. Every so often when working with equipment, you get this sense of relief when you hear something. You go, "There it is, there's the sound that I've been wanting to hear, that I've heard in my head all this time." The 256 does that a lot. It's kind of like when you first plug a Les Paul or a Telecaster into an AC30. Or if you plug a Gretsch into an AC30 and you realize, "Oh, so that's how it's supposed to sound." Or the first time you play a Rickenbacker twelve-string, Farfisa, or sing into a U67. You go, "Oh!" It seems so obvious, but I always feel that one of the truest things that I say in my recording classes is this: "How do you make a great sounding record? You make great sounds and capture them well."

It's impressive that while you're certainly the biggest gear freak I know, it's probably your people skills that factor most during a Pogo session. Do you weigh those aspects equally for this job, or does one matter over the other?

I believe that the most important thing about a session is what you say after the vocal take. It's what I call the moment of truth. It will set the direction for the entire relationship of the band to the person who's helping them make a record. The singer comes to the end of a vocal take, and says to you, "How was it?" I've actually heard people say, "It sucked," or something equally negative. At that point everybody should just go home, as far as I'm concerned. The process will not be positive from that point on.

You're talking about studio staff, rather than band members?

That happens too. You have to be very aware of who gets hold of the talkback switch, and what they say. It doesn't mean you have to say, "It was fantastic" if it wasn't. You want to give the best feedback, the most honest assessment of how it was. "How was it?" "It was really good, but I think we could get this part better." Take that apart: "It's really good." If it really was good, that's a good way to start. "But we can get it better." It's not accusing or finger pointing, like, "You did this, you were flat, you were sharp, you were early, you were late." "We can get this part better." Again, it's the part. It's the vocal. It's the performance. "It was a little flat here, and during the second chorus, I think we can bear down a little bit more." It's good to be careful about those kind of things. I'm trying to encourage people to do the best they can. It's a position of great trust and responsibility. We're not just there trying to magnetize tape, or trying to move air. We're trying to realize people's dreams, their subconscious feelings and thoughts and views and philosophies — their professional dreams and aspirations, their personal dreams and aspirations. It's a very grave undertaking in many ways. Everyone has their particular style of doing it, and I have a more calm, encouraging approach. It doesn't work for everybody. I've seen people get results by being abrasive and pushy, and maybe if the music needs to be tense and driving, that's appropriate. I rarely do that.

But you do, if necessary?

If I have to, I'll say, "You know what, it's not rocking. You need to bear down more, it sounds weak." I usually don't come out and start pointing fingers at somebody. It's rare that I feel I have to get assertive. It's something that I'm aware of about my own character, though. It's great when everything goes smoothly, and everyone's relaxed and having fun, which I think is the best state to be in. I also don't want to pacify everyone and make records that are low energy. You do what's necessary to get results. Sometimes you do it in ways like turning up the headphones, adjusting the lights, setting your own energy level.

It's difficult imagining when you wouldn't get better results by being a partner to the client, rather than an adversary. It becomes a question of how quickly you can establish that bond.

I think that many human relations, including collective relationships, are determined in the first thirty seconds. You establish the entire tenure of a class or session in about the first minute. The dynamic tends to crystallize at that time and stay that way. Whether people are gung ho, talkative, relaxed, or apathetic, these things seem to happen in the very earliest moments of the relationship. That's something else that I try to be careful of in sessions. I try to be the one to open the door. I try to have the proper attitude when I do it. I don't know if you've noticed this, but I have a postcard next to my door of a horse wearing a helicopter beanie and giant sunglasses. It really makes me smile. I have it there for a reason. I look at it before I open the door, because it makes me happy. It allows me to start things off on the right foot.

What a great anecdote!

It's the truth. I've been on sessions where you get a grouchy person answering the door, or the telephone, and it sets a negative tenure for everything. It's almost always impossible to recover from.

In an industry where the norm is to be overworked and under slept, it takes fierce resolve to be cheerful every time you greet a client.

Exuberance is one of the best qualities anyone can ever have. What will make a bigger difference, the kind of console I have, or my attitude when I open the door? What's the more valuable material tool? A multiple hundred-thousand dollar console, or a twenty-five- cent piece of cardboard with a picture of a horse on it? It's entirely possible that the piece of cardboard will have more influence on the music, its meaning and its success in reaching people, than any amount of hardware. Having said that, it's nice to have the hardware, if you know what to do with it.

The hardware is there to help the goofy horse do its job, helping you to do yours.

I absolutely love what I do. I'm excited about it every day. Today someone asked, "What are you doing tomorrow?" I said, "I get to play a gig, and I get to do a recording session," and that's how I feel about it. I get to. It's not, "I have to record this band, and then I have to go somewhere and play." I can't believe that I've been this lucky to meet so many interesting and lovely people, from whom I've learned so much, and to engage in a magical, creative process like this. To get to create my own environment and make music on my own terms is truly amazing.