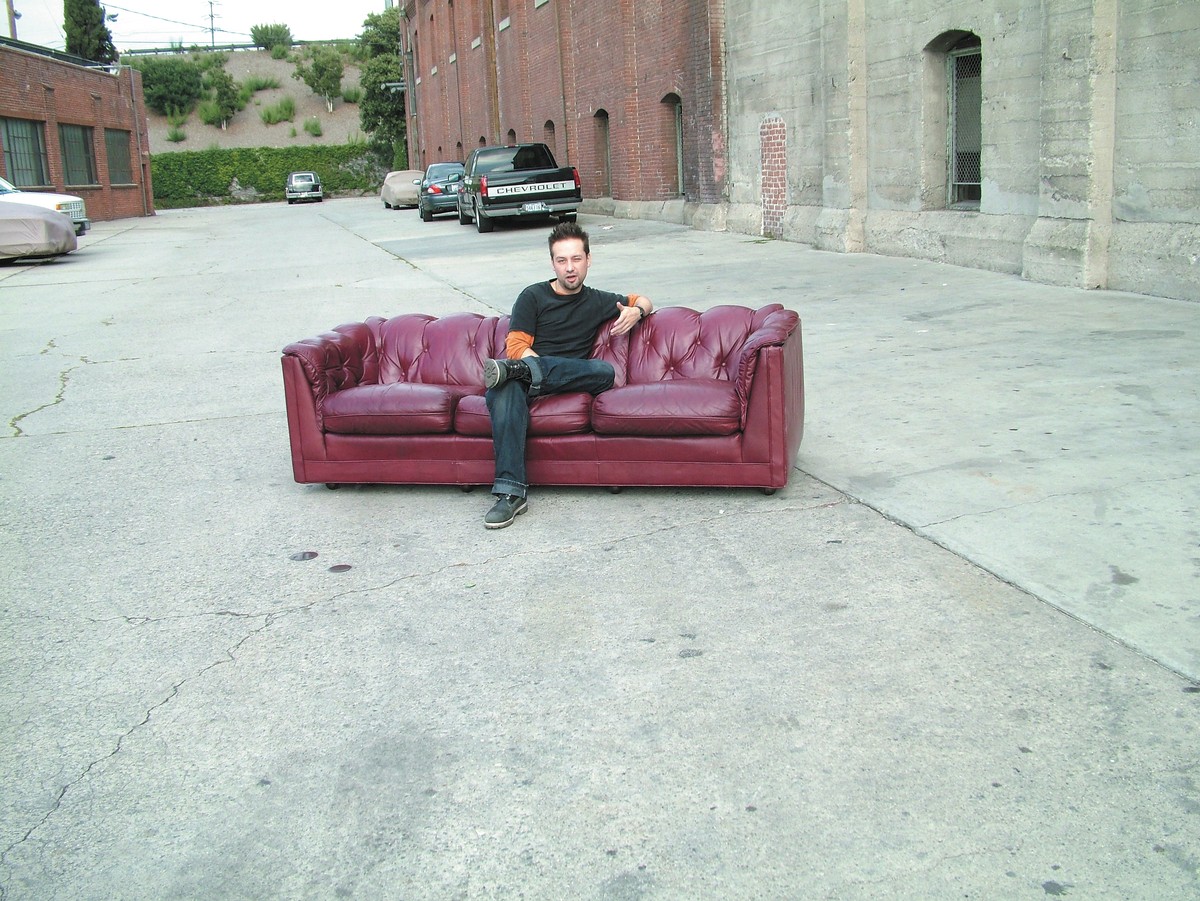

Alex Newport first made a name for himself in the late eighties with the heavy, sludgy sound of Fudge Tunnel, an English band that was around from 1989 to 1995. He moved to the states in the early nineties, starting the side-project Nailbomb, becoming a producer and later an engineer. He's well known for helming guitar-heavy productions for artists like The Locust, Mars Volta, At the Drive In, Me First and the Gimme Gimmes, Polysics, Melvins, The Icarus Line and many others. I met up with Alex in Los Angeles at his studio, Hot Head Recording, which is tucked into a loft in The Brewery (the largest artist complex in the world and where Pabst Blue Ribbon used to be made). He works here often, with modest equipment and a smallish room, but also travels around the country and world to work in other studios. Alex is a soft- spoken, thoughtful person, and a joy to spend time with — interviewing him was like hanging out with an old friend — we had a great time.

How did Hot Head start?

Sometimes it's like, "Oh great, we can only afford three days for that if the studio is five or six hundred bucks a day." So, coming in here I can keep it really low and then be like, "Oh for the same money we can make an album in two weeks." As long as I can just cover the cost of the studio — I mean, it's a work in progress. I keep adding stuff as I go.

Who doesn't?

Right, but people are like, "Are you going to put a Neve in here and HD?" I'm like, "No, because then I'll have to charge every band six hundred bucks a day." If I have a pretty decent budget, I'll go to a big L.A. studio and track the drums and then I'll come here. I remember doing the last Locust album — we were in Grand Master, which is a really nice Neve room. We were doing vocals and guitar overdubs using one mic and one set of headphones and we were paying fifteen hundred bucks a day. Because the studio was that expensive, we couldn't afford too many days. I won't say that we cut any corners but we didn't have time to mess around, that's for sure. By contrast, I just did the new Locust EP and okay, the equipment is not quite as nice as it would be at Grand Master, but we got to spend three days just doing guitar tracks and Bobby [Bray] has a billion different pedals and he wanted to try different things. Also, you don't feel like you're on the clock so much because I can keep the cost fairly low and it's not like, "We're paying two thousand a day for this!"

There's less pressure.

There's a lot less pressure. If I have the budget I'll do the drums somewhere else and come here and do the rest, but sometimes the bands just choose to come here and do the whole thing start to finish anyway. Everybody has been really happy so far.

How much of that do you think is just you becoming a better engineer over time?

Oh, I think it's all of it.

What are you using for Pro Tools right now?

Don't laugh — there's a TDM on the way, but what I have right now is a Digi002, outboard conversion and two more channels [S/PDIF]. I've got eighteen ins and outs. You can make it sound really great if you know what you're doing. The way I do it is, the drums, bass, guitars and lead vocal are all mixed separate and then all the backing stuff — the percussion, the extra noise and stuff like that — are just a stereo mixed within Pro Tools, which is not perfect. I am looking to buy a TDM system now just because this place has gotten so serious. I never intended it to be that. I literally thought it would just be for doing some vocal overdubs and guitar solos.

That's kind of what I gathered when I looked over your equip- ment list. "This looks like a studio that just accidentally started getting busier."

That's absolutely what it's been. I never expected to do a whole album project start to finish. That's the music business, too, because right about the same time I opened this place was when a lot of studios started closing and a lot of labels were saying, "We don't have those kind of budgets." I'm actually going to be looking for a new place to build out because I want to do a bigger space. I mean, it's all of a sudden just gotten very, very serious. I never wanted to be a studio owner!

[laughing] Yeah, I didn't think so.

You've got to be crazy to own a studio because you've got to deal with getting paid, you've got to deal with expensive equipment that breaks all the time and dealing with musicians that are coming by and peeing on your rug or whatever. But since I started doing it, it's great. I can really be so much more flexible in the way I make albums. I should've done this years ago.

If you were to move out of the space you're in, what do you think the dangers would be say, of taking out a loan, having a larger lease or having more overhead as far as impacting your career is concerned?

Well, there is that situation of having to do projects to pay the bills — I'm fortunately, for the most part, not in that situation. I can afford to turn down the projects that I don't one hundred percent believe in.

Right now.

Right now. That's the disadvantage of having a bigger space, I think. I think I could set it up where it would be a commercial studio. Right now, my space — no one else works in there except for me because I live in there. I can't have a band in there [with another engineer] when I'm living there. It's definitely something I have to kind of do carefully. But I like to do everything in sections. I would never take out a quarter of a million dollar loan and just go for it. It's just "upgrade as I go" and keep moving towards it.

What kind of things do clients ask you about gear-wise when you're first talking to them?

It depends. There are two kinds. There's a kind of client who just assumes that everything brand new is the best so they'll come in and say, "What's this old board doing here? Shouldn't you have a Mackie? Isn't that the new thing?" Then there's the other kind of client who is obsessed with vintage gear and believe that only vintage gear is of any use — so if you don't have a studio full of old tube pres it's not as good. It's awesome to have that stuff, but the most important thing is right here [points to head]. That's the thing with my studio — I'm making records on TAC Scorpion with just a couple of outboard pres and a couple of outboard compressors and some functional, average mics. I'm making records that I'm really happy with and the bands are really happy with. I take my time on tuning the drums. I take my time tracking guitars — get the mic in the right spot and to me that's so much more important. If something isn't mic'ed right or if you're just doing it the wrong way, then no amount of vintage gear is going to help you.

No, it doesn't.

It's definitely nice to have, but I don't think it's the most important thing in making a record. For example, I'm getting better drum sounds in my studio using [AKG] 414s and just average, okay mics because I'm able to spend longer tuning the drums, which is much more critical to the sound than the mic sound. If I'm working in Sound City doing drum sounds, it's expensive and I've got to do it quick — and sometimes it's like, "That snare isn't right, but I've already spent two hours, we're runnin' out of time." In that case, it doesn't matter how many vintage tube mics you've got, it isn't going to sound right. The only way it's going to sound right is if you get it right at the source.

I know you have a producer manager. Have you ever found that management is finding work for you?

Rarely, I mean, it's not easily...

Do they bring someone to your attention and say, "These people are thinking of working with you and they contacted us?"

Nine times out of ten, a band contacts me and we get the creative stuff out of the way and say, "This seems like it would work out," so then they say, "How much?" and I say, "Go talk to my manager." Very occasionally there's been cases in the past where my manager met someone who said, "Hey we're looking for a producer for this kind of stuff. Do you have any ideas?" And they said, "Oh, why don't you call Alex?" Sometimes it goes like that, but generally speaking I would say that it's more of an administrative and career guidance issue. Most of the stuff is bands coming to me.

You've worked within a certain genre quite a bit, or a certain sort of feel, I'd say, more than a genre, so a lot of times bands are going to be searching you out because your name is going to be on the back of records.

Yeah, it's word of mouth and most of it is, "We heard the At The Drive-In album or The Locust album that you did and we think it sounds great and we love your work."

Do you feel somewhat pigeonholed sometimes?

Yeah, I've tried really hard and I am continuing to try — for example, The Locust — a great example. I don't usually work with bands like that — that sound that heavy and that aggressive. I tend to prefer bands that are more vocal or ensemble oriented. I like heavy guitar stuff, and that's no secret, but generally speaking, I'm looking for songs, you know?

With The Locust, what did you hear that you liked about them?

Well, I've seen them play and just the sheer energy and the fact that what they do, they do so well — it might not be one hundred percent my thing all of the time but they do it so well and they're really interested in pushing boundaries and that's what I can help bring to them — trying to help them develop those ideas. Of course, since I've worked on their album and everybody loved it, I now get a hundred calls a month from bands that sound exactly like The Locust. I like The Locust, I like what they do, but I don't want to be working with a bunch of bands that sound like that. It would be pointless.

There would have to be something else in there that you heard that spoke to you.

Yeah, so I'm deliberately turning down all those bands. The same with Sepultura — for a year, every band that called me was this gruff metal band — that's not my thing particularly. With Mars Volta, I get a lot of bands that call me that sound exactly like Mars Volta and I go, "I don't want to do this." I'm interested in finding new bands that are doing something different and trying to develop that.

Within what you're doing, have you pulled in projects that have been different recently?

I really try to keep it as varied as I can. Sixty to seventy percent of stuff I do is loud guitar rock. I am trying to vary that and get away from that a little bit, but again, you have to play to your strengths — there's a reason why all those bands come to me. I figure I must be good at that. My favorite thing in the whole world is bands that have that aggressive edge but hopefully they have songs and interesting varied parts too. That's what I'm trying to seek out.

With an aggressive guitar band, do you spend a lot of time cutting to the core of the song and then trying to make the song a stronger thing?

I typically do a lot of pre-production with bands. The first time I ever worked with a producer we thought our songs were great. We thought they were perfect. Our producer came in and said, "Why is this part so long? There's no point for it to be that long. Why don't you try this part in A?" We were like, "Who the hell are you? You don't know anything about our songs." But, we gave in, "Okay, fair enough. We'll give it a try." And of course it sounded way better and we were like, "You're right." You spend so long on songs that you can't see the woods for the trees. A lot of people don't listen to the whole band or to the song. They're listening to their parts. The guitar player wants to make sure that he or she is playing all their parts correctly. They're not really listening to the bass player. Sometimes I get in pre-production and have the band turn way down — like way down. "Now play the song again" and then they go, "That's what you're playing on bass? We're playing totally different notes." They had no idea.

Yeah, the groove was good, but...

That's an interesting concept, too. It depends on the band. Some bands — especially the more aggressive ones — I don't need to get insanely involved and tear up all their songs. Some bands that are really aggressive — it's not so much of a song, but more of a style — it's more of a vibe that works, and even lyrics can be a little bit more amorphous in that case.

It's more a texture.

Yeah. But then like The Locust — it's more of a collage than a song, but still that collage has to be fit together in a dynamic way that makes you feel something. There are other bands that I work with where it is literally a song and that's when I feel like I need to get more deeply involved — even as far as lyrics if it comes to it. I write lyrics too, so I can see where someone has run out of ideas. It's like, I know where you're going with that. You've just stopped too soon.

Verse three is not happenin'.

That can still be a good song, but it's not a great song and that's what I'm trying to get out of them.

Do you think there's ever a fear that you'll be the engineer that doesn't understand the band you're recording? My fear sometimes is that I will be the guy that I hated the first time I went into the studio.

I hope not. I would like to be that guy in twenty years that still is somewhat knowing what's going on in the music industry and trying to keep people pushing things a little bit. Usually if I find bands that just sound very, very generic, I don't have much of an interest in it — unless I feel that they sound generic and they deliberately want to try to expand that and get away from that a little bit — then I might get involved.

Have you had projects like that where you helped them move past their earlier catalog?

Yeah, totally. Especially bands that have been around for a while and start to run out of ideas or who have good ideas, but don't know how to put them together — you start to get self-doubt about the sound of the band. It's a really difficult thing being in a band, especially if you're a very style-based band. If you do one album and it does well — if you do another album on the same theme, people go, "Well that sucks because you're not progressing" and if you do something different, people go, "Oh what happened to the old stuff?" You just have to try to find the middle ground, I think — pushing it a little bit, but trying to still stay in touch with why people liked the band in the first place. Look at Weezer — their first two albums were almost flawless and they're in a really difficult position. How can they top those records without just repeating themselves? Very, very difficult situation. To me, that's where a band like Radiohead really shines as far as their talent.

So you're using Pro Tools in your studio?

I use it fairly minimally, inasmuch as I'm really using it like a tape machine so I'm not using tons of plug-ins. It's actually fairly rare that I use a plug-in. Everything's split up through consoles or outboard EQs and compressors, so I'm not too worried about keeping up with the latest stuff as long as I have a solid system that's comparatively bug free.

Yeah, it could be an older operating system and an older version of Pro Tools, but the file format is going to be the same. If you take it to another studio, you just open them up as tracks — they're gonna be there.

It doesn't necessarily bother me. It's more of a client thing. That's the thing with Pro Tools — it's all in how you use it. The temptation to fix every little detail, Auto-Tune everything — sometimes it's hard to resist it. I really appreciate growing up working on tape and working on 8-track and 4-track where it's like, you have to EQ things to tape or mix the drums to tape because you don't have the option. I think it's a good way to learn because you still retain a little of that, "Well I could fix this, but I'm not going to." You just have to use your taste in how much you're going to fix. The great thing about Pro Tools is how quickly you can do edits. In a strange way I can make things sound live-er on Pro Tools. I was working with a band in New York and they were working on songs. The drummer was having a hard time with this song and we did five or six takes — he eventually got it on the sixth take, but there was a guitar solo in the middle of the song and for the first five takes, the guitarist was just rippin' on the solo. It sounded great. When we got to the sixth take he had got tired of playing it and just really half-assed it. So, we're using the drum track on the sixth take and when it came to overdub, "Okay let's try that solo again," and of course he couldn't play it. He's sitting there in the control room and he couldn't connect, couldn't play it — so of course I went back into the first take, pulled out the solo. It was a slightly different tempo, so I had to do some little nudges, each bar to make it fit. Within ten minutes, it fit, it sounded great and it sounded like a really inspired solo that really worked and made the song. Without that I would have had to settle for a less inspired performance. You can choose to use it how you want. It's just unfortunate that the temptation and the amount of things to do are so easy to do that it's hard to resist it sometimes.

In a previous interview you did with Roman Sokal [formerly on the www.tapeop.com "Bonus Articles"] you were adamant against using digital...

I absolutely was.

I read it the other night and I was laughing. What changed for you and what changed with the technology?

Not so much the technology — although the technology is improving — it was just, back in those days I'd heard records done on Pro Tools that sounded really terrible and I just made an assumption that it was the system — the hardware — that was to blame for these awful, thin, phase-y, horrible, edited-to-hell sounding records. So I just decided it was the devil incarnate and I didn't want anything to do with it. What happened was I started to do a lot of mixing for other people. They'd bring me their stuff on Pro Tools and I'd mix it and I'd listen to it and I'd go, "These drum tracks sound awful. Pro Tools sucks." Then, there was one session where the bass was out of tune and so I was like, "We have to re-do this bass. It's out of tune." So it's set up to record, and we record into Pro Tools and I go, wait a minute...

It sounds fine.

It sounds exactly like it does when we were recording it. So, wait a minute. Maybe there's something in this. It took me about six months to be fully convinced. I did a lot of A/B-ing and I was going back and forth — some albums on Pro Tools, some going back to tape. I started to realize it's all in how you use it, just like anything else. I mean, tape can sound pretty bad. If you look at thirty inches per second and you keep your levels really low or really high — it's not a sound that I particularly like. For me, it's difficult to say there's a tape sound or a Pro Tools sound.

When you use tape are you running at 15 ips?

It's always 15. I just did an album with this band Numbers for Kill Rock Stars and we did the session at Tiny Telephone, which had no Pro Tools. It was the first time in about a year going back to tape and I did 15 ips IEC, the European standard, which has about two or three dB less tape hiss.

Yeah, I've done that on mine.

Yeah, and that's the way to go. To me, that's when tape really sounds good, especially for rock stuff. It was funny because working with Numbers, we actually did five songs at Tiny on tape and then they came to my place and did another five songs on Pro Tools, and it was really interesting to see the difference.

Did they feel different to you in the end?

No. Well, inasmuch as the ones that were done on Pro Tools were more accomplished because we were able to do stuff more quickly. We were able to salvage parts from other takes and get a truer feel and it opened their eyes because they were very much sort of on the fence about it. But at the same time, they were really in awe of me cutting tape. Bands come to me talking like I used to talk five years ago. "We want to work with you — just not on Pro Tools." My answer every time is, "It's not relevant. It's whom you work with and how you work that dictates how it sounds." My main argument is, if you take a kick drum and record it into Pro Tools, and at the same time record it into tape and you sit there and A/B, of course they sound different. There's a slightly different sound that you can hear, but a kick drum, by the time a record is finished, has been EQ'd twice, gated, compressed, the stereo bus is compressed — it usually has some effects and maybe you had a room mic, maybe you don't — there's so many other things. Whereas for example, if you have a mic on a snare drum or on a guitar and you move it 1/4 or 1/8 of an inch — bigger difference than the difference between tape and Pro Tools. There is a little bit of a sound — you just have to be careful how you work. Pro Tools doesn't have as much depth to it. Everything seems to be really up front and very clean, so sometimes you might have to add a little bit more reverb or a little bit more room mic than you might have to on tape.

A lot of times I'll have it running with the internal mixer and doing overdubs through 2 channels out. Everything just feels kind of crappy and just sitting there, but as soon as you spit it out into different outputs, bring it through a console and mix it down to something else, it seems like all of the sudden, we've got a little room to breathe.

Right. I think that's really important — going through the stereo bus within Pro Tools is not really adequate. I mean, I've mixed a couple of records doing that and they came out okay using all plug-ins, but for me it's really not ideal. It's much harder to do. You can make it work. I'm doing a lot of stuff these days where bands record themselves in Pro Tools at home, which can or cannot be a pretty bad situation. Sometimes it works okay. There is a proliferation right now — especially in California — of people who have a Pro Tools in their garage and they're set up recording their friend's bands, and sometimes I get stuff that sounds really good and I go, "What studio is this from?" and they go, "Oh, it's our buddy's garage." There's other stuff that I go, "Hmm. What ocean did you record this at the bottom of?" I enjoy the challenge, though, because it's Mr. Repairman. It's like, take something that has a pretty decent performance, but it's recorded absolutely terribly, and actually mix it and really kind of pull out all the tricks and all the stops and make it sound good and then when you're done the band goes, "Oh my god!"

Have you had any time these days to be an artist — as a musician?

Increasingly less so and in fact, there is a band I've been playing in with a couple of guys from San Francisco — really talented guys...

Theory of Ruin?

Yeah, Theory of Ruin. But between my schedule and their schedule...I mean, Ches [Smith] tours with a lot of people. He tours with Secret Chiefs 3 and Trevor Dunn Trio — he does a lot of stuff with those guys, and if I ever do have any free time, chances are he's on tour somewhere. I also think I started to realize I could be a producer or I could be a musician and either one of them really well. Doing both of them really well at this point is hard.

Do you regret that decision? It's kind of a bummer to leave things behind that you enjoy doing.

Right, but at the same time we've been a band for quite a while and it's going to be hard for us to progress musically beyond what we're doing. We'd need a lot of time together to do that and to really progress, and we're not going to have that time. We're still a band, but it's a very loose situation at this point.

See what happens.

At the moment I don't miss it that much. I've been in bands a lot of my life. Fudge Tunnel was a band for seven years. We toured for those entire seven years, and of course being twenty-one makes it much easier. Being thirty-five and having mad bills is like, "Oh, I'm going to sleep in the van on the side of the freeway in New Jersey tonight?" Yeah, brilliant.

While I'm thinking about my studio sitting empty at home and bills piling up.

Right, totally, yeah. So your priorities start to change a little bit.

I can definitely see that. With Fudge Tunnel were you producing some of these records?

Towards the later dates. That's how I got into recording, was working with that setup. Originally we had producers and engineers that we worked with. Colin Richardson, who I love, and Iain Burgess recorded one of our records. Great guy. I learned a lot from him. We'd do two takes, and he'd say, "Well, the first take was good, but you fucked up the end. The second take, the start wasn't so hot." He's pulling out the tape not even looking at it, cutting it and saying, "So did you see the game on Saturday? Liverpool killed us on that game!" and we're just, "What're you doing to our tape?!" He'd be like, "Oh, it's fine." Put on sticky tape, press rewind, hit play, didn't even look at the tension, walked away — perfect edit. That was like when I was, "I have to do this job. This is what I'm put on this planet to do."

Iain did a fantastic job on some of the Big Black records too. I think sometimes people think maybe Steve Albini produced those records. I'm sure he had input of course, but Iain was really the catalyst for getting those kinds of sounds.

He really was great. It's strange because a lot of those records, like Atomizer, are actually produced. Obviously Big Black was a very raw sounding band — but if you listen closely, there's a lot of stuff going on in the mix. It's just done so tastefully that it doesn't seem overdone. Big Black is one of Fudge Tunnel's main reasons for being a band. Between Big Black and Black Flag, that was kind of what we tried to mix, the kind of real abrasive, edgy, scratchy stuff but, with more sludgy, Sabbath-y kind of sound under it.

When you're producing a project are you usually engineering it?

Oh, always. I am a producer first and foremost. When I first started working I produced and had people engineer, but I was, generally speaking, unhappy with the tones that they were getting. Or I felt like I couldn't relate the sound that I was looking for to them. Or I thought that they didn't really know what they were doing, or by the time they had figured it out, the moment had gone, and so I quit producing for about three years and just started engineering — working at studios and figuring it out. Finally when I felt like I knew what I was doing I came back to it. Now I only produce and engineer. It's such a direct link to the performance and how that tone should be and I just go bam, bam and it's done. Just asking someone else to do it seems so complicated. You have to wear a lot of hats, because you're looking at meters and you're listening for whether somebody's in key and you're trying to make the band feel comfortable. It's a lot. It's a lot of stress.