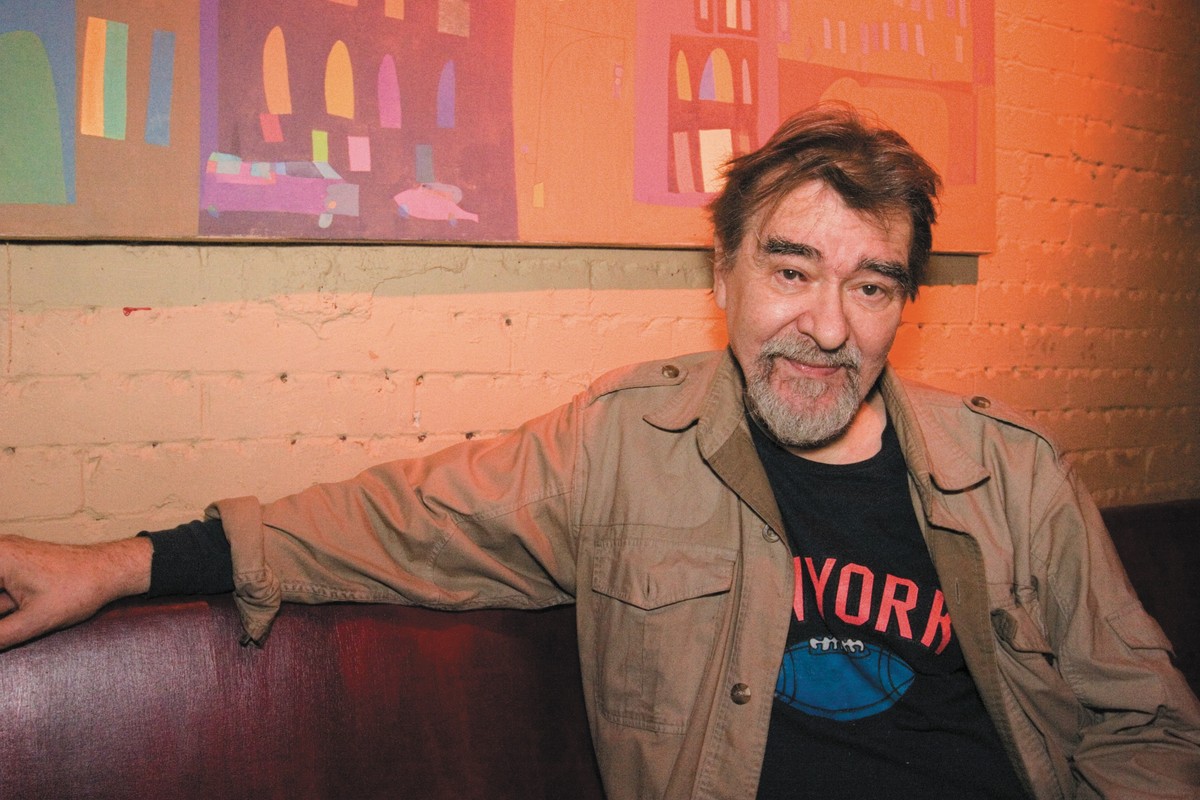

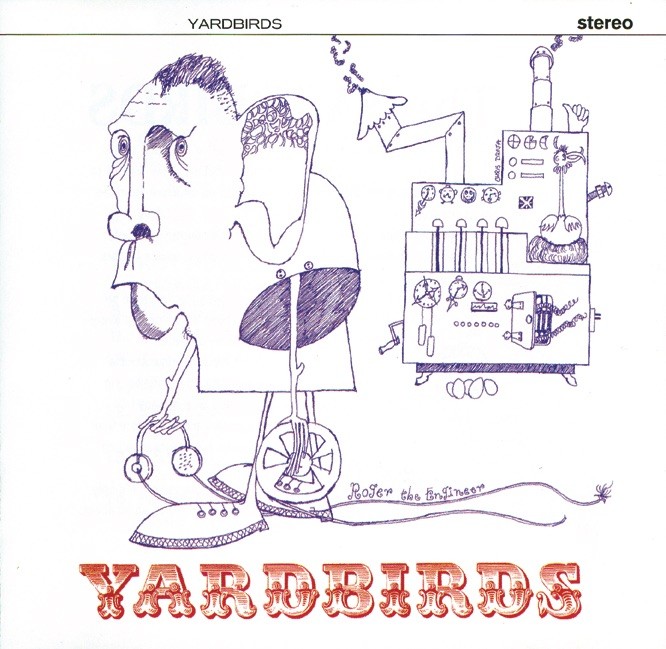

At times it can be difficult to believe that someone like Giorgio Gomelsky actually exists. For almost fifty years he has been at the center of so many significant cultural events and initiated so many things we take for granted, it seems that he must be a fictional composite of dozens of people. But no, he's for real — a flesh and blood man almost painfully committed to the highest ideals of art and its communication. One could call him a producer — and, indeed he has been — he produced records by John McLaughlin, Julie Driscoll, the Spontaneous Music Ensemble (with Derek Bailey), Vangelis, Magma and many others. But he also is/has been a manager, a club owner, an impresario, a raconteur, a facilitator, festival organizer and astute political theorist. However, unlike almost every other person in the music business, he has usually been seen running away from the money rather than towards it. If there is an underlying thread to his life story, it is that whenever things started getting too close to the mainstream, Gomelsky lost interest and moved on to another uncompromising situation. For this article, the focus is on what many people feel is his most important contribution to the world of music — his association with the seminal British rock band, The Yardbirds.

The first album by The Yardbirds [Five Live Yardbirds] was a live recording. What was the decision process that went into this?

Very simple — in England we didn't have the recording business that was so established and dominant as here [the USA], you know. So bands really had to gather an audience by playing live. This was something they could do. Most English bands were very good live bands.

They were all club bands.

In England the club idea was not like here. It wasn't as there was a physical place and that was it. It was evenings run by promoters in the back of pubs who had little rooms where music happened, and people used to go and dance. The English music scene from skiffle onwards — even before that, traditional jazz and stuff — really took place in the back of pubs, and those were "clubs."

You're talking about the young British bands?

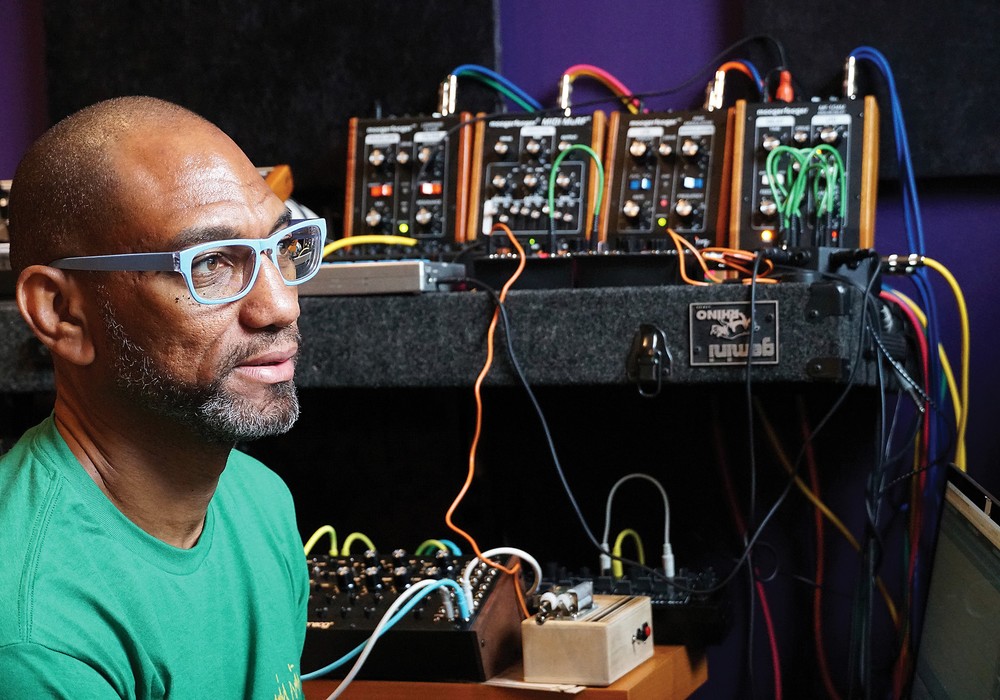

The Rolling Stones, The Yardbirds. There were a couple of blues bands outside of London. This wasn't rock n' roll — this was the blues. The rock n' roll thing came in afterwards. It's very interesting how the possibility of recording happened. The first time that Sonny Boy Williamson came to England he stayed with me. I took him in my car and we went to all these places where there were blues bands. In the South End there were The Paramounts that [later] became known as the Procol Harum. In Birmingham there was the Spencer Davis [Group] where Steve [Winwood] was like, fourteen and playing the organ. In Newcastle there was a band called the Alan Price Kansas Blues Quintet, later known as The Animals. I ended up there and found a guy, Phillip Wood, who had a portable Ampex machine — mono. He had done demos for The Animals — a kind of straight, innocent character, but he had this equipment. I think it must have been the only Ampex one inch (whatever it was at the time) portable recording device. When I saw this I went, "Wow! Let's drag this into the club." And we recorded Sonny Boy with The Animals the first time that Sonny Boy went up there. I convinced Phillip to come to the next venue. I did a big thing on February 28th (which was my birthday) in 1964, in Birmingham. It was my first edition of a British blues festival — Sonny Boy, Rod Stewart and Long John Baldry — anybody that could play a couple of blues numbers would be on this, and that's how we convinced the Marquee to let us have a go at recording the live stuff.

What do you think caused this seeming explosion of bands at that point?

What creates real phenomenal turn-arounds in civilizational culture is the love of something. The love of the blues became very important. Either it grabbed you or it didn't, but the ones that got grabbed by it soon became musicians because they loved it so much they wanted to play it. Rock n' roll had a period of success in England, but it was based on the kind of commercial rock n' roll you had here. You had the Elvis Presley imitations like Marty Wilde and Billy Fury. A very significant development was the opening of the Marquee Club — owned by jazz musician Chris Barber. At one point it was suggested that [British blues legend] Alexis Korner would get his own night at the club — a blues night. This became the magnet for all the young blues players. The blues and skiffle thing were more [for] student types. The commercial type thing gave way to people like Cliff Richards and The Shadows. It had nothing to do with blues. When The Yardbirds came to the point of making some kind of a statement, making a live album was the answer. We were playing to a thousand people in the Marquee and the atmosphere was unbelievable. That was the thing that I started off doing at the Crawdaddy Club with The [Rolling] Stones — just do forty-five minute sets —...