Mac McCaughan is well known for his 20 years as the front man for the Chapel Hill, NC, band Superchunk, co-owner (with Laura Ballance) of the influential independent record label Merge Records and the leader of his side-project-turned-group, Portastatic. Mac has worked with a number of interesting engineers and producers, and has also learned more about recording as he crafted a number of albums at home. I've always held Mac and his compatriots in high esteem for their great music and fair business practices, so it was a treat to finally meet and chat.

Part of the sonic imprint of Superchunk is a wall of noise. You guys have deviated to certain degrees here and there, but that's sort of a sonic signature.

As we went along we started breaking stuff down a little bit more and having the guitars play countermelodies and single guitar lines to relieve the solid wall of guitars a little bit. A wall of guitars is more effective when it comes it after there have been quiet parts.

That's The Pixies!

Yeah, exactly. I think that with Superchunk it took us a long time to make the transition from live to studio, and I don't know if we've ever gotten there. I feel like our last couple of records, Here's to Shutting Up and Come Pick Me Up (and even Indoor Living to a certain extent) were studio records more than the first few albums. When we play those songs live they sound like Superchunk. With those records though, people are like, "What is this? This is not what I want to hear when I listen to Superchunk."

Did you get feedback like that?

Oh, definitely. But for us it's what keeps it interesting. I think it's still a learning process — how to make things translate in both situations. When we did Here's to Shutting Up I did the string arrangements and I'd learned a lot from Jim [O'Rourke] about doing that. We were piling a lot of stuff on, but Brian Paulson's really great about finding a place for everything. Something that I think is really hard to understand when you first start out is that you don't have to hear everything. I remember making our first record [Superchunk] with Jerry Kee at Duck Kee Studios. I think it was 16-track, 1" tape. There are so many guitars on there — I remember Jerry saying, "You're not going to be able to hear any of these." Of course I wanted to bury my vocals, but at the same time I wanted to hear every single guitar track, and it becomes impossible. I think everyone wants to make sure that they're hearing all the parts when they first make records. "There's this one cool note that I hit at this one point and I just want to make sure that's loud enough." If you make enough records and you work with good people who know how to mix, you realize that it can be there [even if it's not] hitting you over the head.

You can tailor the sounds to be in a narrower range.

Right. John Plymale is great with that. I mixed Be Still Please, the last Portastatic record, with John as well as Summer of the Shark. John's a master of the EQ in terms of what you're saying. Instead of just panning something to a different place or turning it up or turning it down — just EQ'ing something so that it sits in the right place and you hear it. When I brought in Summer of the Shark and we had to dub all that stuff out of my Roland VS-1680 two tracks at a time, it just took for fucking ever. Those tracks had been recorded onto reel-to-reel 8-track, then dumped into the 16- track. There was a guitar solo that was on a track with some other guitar but the guitar solo was slightly out of tune and there was no way to separate it out — but he EQ'd it so that it didn't sound as out of tune.

Oh yeah, all those tricks.

With Portastatic I was kind of always doing the same thing because I had a 4-track and one or two mics until I got the 16-track, but I was learning all this stuff along the way.

Do you feel like you learned about song arrangement too?

I think so — it probably has developed in a certain way along with learning about the recording stuff, especially with Portastatic. Because a lot of those songs are written as they are recorded, starting with a drum machine and a weird keyboard part and then making that into a song. You definitely learn how to leave room for things that are going to come in. One thing about working with O'Rourke and listening to his string and horn arrangements is that his arrangements are not so much sweeping, orchestral string arrangements — it's more like pop string arrangements that are really cool accents and countermelodies. I think that around that time I was listening to a lot of Tropicália records — stuff comes in unexpectedly, is in a range that you don't expect or certain parts never repeat — the part just keeps on changing as the song goes along. I think for the last couple of Portastatic records I was writing with that in mind, knowing that there would be strings and leaving space for those — also, super simple things that for whatever reason just didn't occur to me for a long time, like doubling a bass line on an electric piano and having them both in there. Learning not to worry about whether you're going to be able to tell what something is or to hear it, but it just adds to the overall picture in — if you took it away you would notice.

You have a handful of new songs that you've written with the band — are you road testing those a lot?

Because we haven't been playing that many shows over the last few years, we usually do one new song in a set. Since we know we won't have a record coming out any time soon, and because we know that people coming out to see us once a year don't want to hear a bunch of new songs that they've never heard before, we try to mix stuff in that we never played live before or songs that we don't play that often. We put out a single last year, "Misfits and Mistakes", and we play that live. We haven't put out a record in seven years — if people come to see us they're fans and they probably want to hear all different kinds of stuff. But it's always better when we record songs after touring with it for a while. When we did On the Mouth with John Reis in Los Angeles at West Beach Studios, we toured to get out there with Polvo, so we were getting to work out a bunch of the songs.

That's a great idea.

When we did for No Pocky for Kitty with Steve Albini, we did that in three nights in the middle of our first nationwide tour. I remember we had a day off in Tuscon, Arizona, and we stayed with these people that we didn't even know. We set stuff up and practiced. We learned "Skip Steps 1 & 3" in their living room. We were literally learning songs as we went around the country, still trying to get stuff down for the record. Usually we're a little more together than that.

What drew you to work with different producers and engineers over the years?

A lot of it is hearing records that people have worked on. When we worked with Jerry Kee, he was a guy that had a studio in Raleigh, NC. Around '86, '87 all of these bands found out about the studio in his house. Jerry was in bands, but not punk rock bands. The bands that I was in — Wwax and Slushpuppies — plus Angels of Epistemology, Black Girls, Egg — were on a 7" box set we put out called Evil I Do Not To Nod I Live - all recorded at Jerry's house. When those bands broke up and Superchunk started doing stuff, we recorded there. That is where we did our first record and a bunch of singles — it's just so comfortable recording at his house. For the second record, No Pocky For Kitty, we wanted to do something different. I was a big fan of the first Pixies record [Surfer Rosa] and more importantly a Big Black fan, so we went to Steve Albini. When we went to Fort Apache [to do Here's Where the Strings Come In] we wanted to do it with Sean Slade and Paul Kolderie. At a certain point they cut down the amount of time that they could work on it and so they recommended Wally Gagel. We didn't know who he was and he ended up being great. I really like the way that record sounds. With Jim O'Rourke, I really liked the Stereolab records that he did and his solo records. There's a band on Merge called The Broken West that was in the studio recently and they were working with someone [because] they really liked the way his records sounded. They were about halfway through the record and I saw Ross [Flournoy] from the band and I said, "So, how's the record going?" He said, "Is it normal for the producer to scream at you?" I was like, "No, that shouldn't be happening." Luckily we've never had a situation like that.

That doesn't sound fun.

I think everyone that we've worked with has kind of been vetted to a certain point. If Corey [Rusk] at Touch and Go is recommending Brian Paulson, you have someone who you trust recommending someone. When we're recording we work long hours because we have a lot to do — probably driving the engineer crazy. With Jim O'Rourke we were working probably twelve or fourteen hours a day and then he was going home and working on something else.

I don't know how.

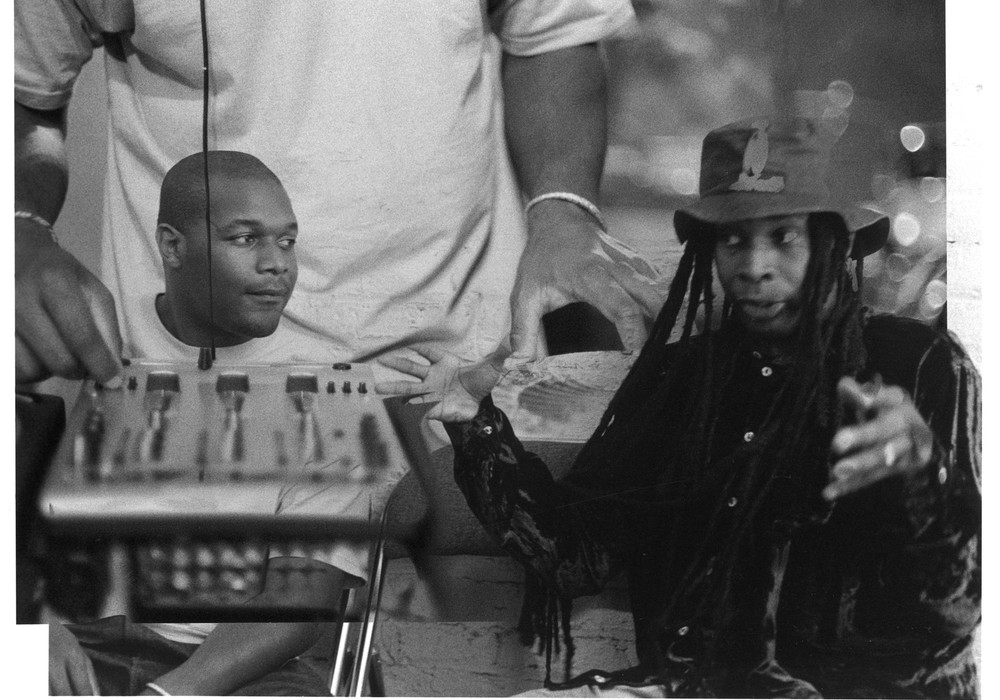

Meanwhile, he's only eating cookies and smoking cigarettes. I remember at one point I was sitting behind him. He was at the mixing desk listening to a mix and writing something down, and I just saw the pencil sliding and he was falling asleep. We were like, "Jim. Go take a nap, man." Our little dorm rooms at Electrical Audio weren't ready yet, so Jim [Wilbur, guitar] and Jon [Wurster, drums] and I were just crashed out on the floor at night in total darkness except for the little gear lights — you have no idea what time it is or anything.

And you're not going anywhere else. You're in the studio solid.

Snowed in. Just going upstairs to maybe watch some basketball or get some espresso. The studio is underground — there are no windows at all in there, so when it's dark it's fully dark. It's pretty disorienting. When I did the last Portastatic record, Be Still Please, I did that at Pox Studios, which is at the Zeno Gill's house in Durham, NC. I'd still go to work at Merge some days and we've got kids. At the same time, every waking minute I'm still thinking about the record. I won't be able to sleep at night and I'll wake up in the morning and I'm like, "I've gotta remember to add that piano part" or, "I've gotta remember to record that guitar part" or whatever. In a sense I might as well be locked in the studio, because when I'm working on something like that I'm obsessively thinking about it anyway.

Other things become more difficult to do.

Yeah, I'd rather be fully absorbed in that thing. It's not practical to do now with a family and everything, but in some ways I'm still doing that anyway. I'm sure it drives my wife crazy, but once my brain is in that mode it's hard to think about other stuff. Working with all of these producers and engineers who have specific ways of working — you end up taking certain things from it that worked for Superchunk or worked for you to do at home — applying the same principles to something that you're recording in your bedroom with just a single [Audio- Technica] 4033. Steve [Albini] had this thing with not wanting to double the vocals. We did the whole album in three nights — recording and mixing — not because he didn't want to spend more time recording vocals, but it seemed like more of a principle. "There is only one of you singing this song. There shouldn't be two of you.' But it's just a fact that my vocals sound better when they're doubled.

To you!

Yeah, because my voice is kind of thin. But maybe I learned the idea of, "Don't do that the whole song, maybe just do it on the chorus." We did No Pocky for Kitty at Chicago Recording Company. Steve had a Coles [4038] on my amp and I'd never worked with a ribbon mic before. I thought, "Wow. It sounds amazing! It sounds like an Albini record!" We did Come Pick Me Up with Jim O'Rourke at Electrical Audio and he had a great way. He knew we had to get stuff done fast. We're good at recording quickly, but he knew when to spend time on something that seemed kind of frivolous, but made the song better. At the end of the song "Tiny Bombs" there are hand claps. Instead of just recording a couple of hand claps and doubling it, he had us and a couple of guys who worked at Electrical out in the big room, about fifteen or twenty feet off of this mic that was in the center of the room. It sounded great! It was fun and it gets everyone out of the process. I didn't even step outside of the studio for the first seven days. Jim knows how to make things sound good, but at the same time he has a good balance of when to leave happenstance stuff in there. He wrote horn charts and string charts, and we had Ken Vandermark, Bob Weston and Jeb Bishop in there to do some horns. When we were recording run-throughs they were just fucking around and playing solos and stuff and we kept that stuff. It sounds amazing.

No red light fever.

Yeah, and recording the real arrangements also, but keeping some of that stuff in there was really cool. We did Foolish and Here's to Shutting Up with Brian Paulson. He was the first one to make us leave the room when he was starting a mix so he could think about it and not have us standing over his shoulder. That was a really hard thing for us to grasp at the time, because you're so used to micromanaging every little thing that's happening on your record. Once you get in the space where you can do that, you trust someone and you can let them take control in that way, it makes the process so much easier because you can step back for a minute.

How much of your time do you spend working for Merge Records?

The label is really my full-time job — that's where I go every day to the office. When I'm making a record it's either afterhours or I'll take a week and just do that. When we had our first kid, our daughter, that made it hard to record at home because kids take so many naps and then she goes to bed at 7 o'clock. My wife has a restaurant, so I was used to being able to work until 3 or 4 in the morning and I could just get stuff done. You get a lot done at 3 in the morning.

You're not getting phone calls at night and that kind of thing.

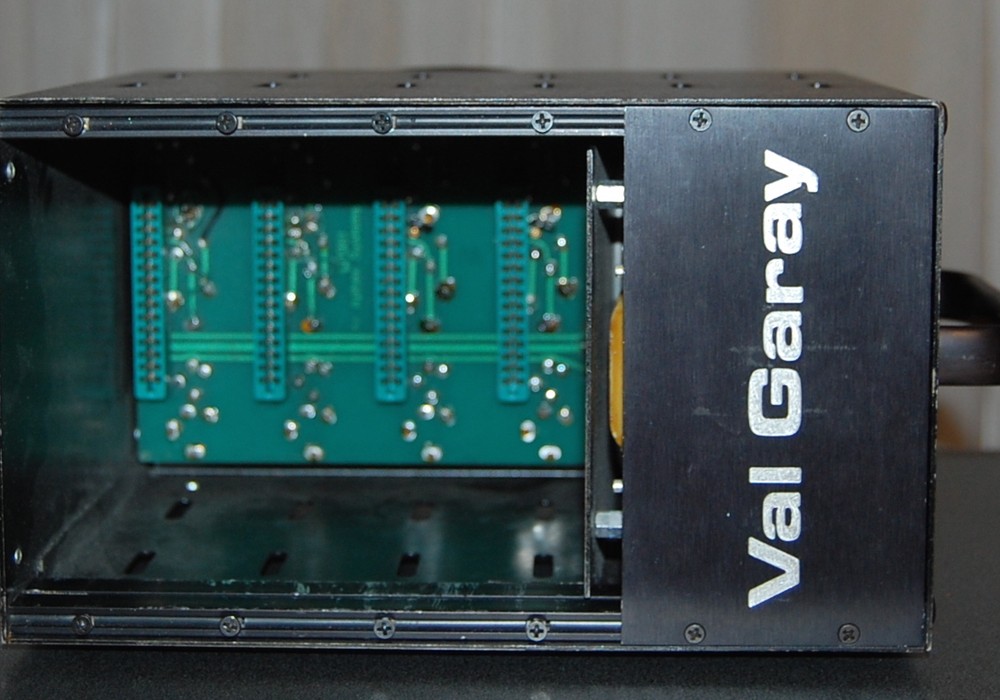

Right. That ended and it became harder to record at home, which is why I started working at other places than home with Portastatic. We're adding a room on to our house to make a studio because now we have two kids. Our second kid, Arthur, his crib is in the middle of the bedroom that was a studio and all the gear is still in there — racks of gear piled up all around him.

You've got to find a way to fit recording into your day.

My problem is once I start something I have to finish it. If I write a song, I have to record it before I forget it. It's hard for me to just record a guitar part and go away for the rest of the day. I've got to record everything that I want to put on there right then. It's not the healthiest way to work, but for some reason it's the way my brain works. My home recording setup started with just a 4-track, some generic mic and then getting a [Shure] SM58 and an ART Tube MP. Getting a new piece of gear, whether it's a new keyboard you find at a thrift shop or a new microphone, can spur on new songwriting because all of a sudden stuff sounds different to you and it gives you ideas. If I'm working on a Portastatic record and I'm at an impasse or I just finished a song and I don't really know where to go next, I just sit down at the piano or start using something that I'm not necessarily as comfortable with and it leads to something. I recorded Summer of the Shark at home and I needed some gear. I borrowed some stuff and I bought an [Empirical Labs] Distressor. That changed my life. That alone gives you ideas.

It changes the signal so much and you can sculpt with it.

When I got the 16-track [Roland VS-1680] I used it as a 4-track with more tracks. I don't try to edit on it. I've worked in so many studios where people are using Pro Tools — I get it. When I'm recording I don't have a lot of time, I just want to be able to record something. I have a single Great River [preamp] channel and a Distressor right now. I have those things with a mic plugged into them and I know I can go in there and turn them on. It's kind of a big relief and it allows you to not have to think about things so much. You can just record. I find even when I get new stuff I still go back to old gear because I'm comfortable. The 4033 — I know it sounds good on my acoustic guitar. I know where to put it. It's easy. It's easier than setting up a stereo mic. I know that going out of the back of my little Mesa Boogie combo amp directly into a recording machine just sounds awesome. It's just an insane distortion. I think it's cool the way you can learn all of this stuff, but you can accumulate these very specific things that you can go back to and use at certain times. I do feel lucky because I could have never afforded to do Portastatic records with Brian Paulson, Steve Albini and Jim O'Rourke in all of those cool studios, but I got to have that experience to the point where I can make my own records in studios now and kind of know what to do.

Do you suggest recording scenarios to bands on your label?

If they say, "We don't know what to do" then we'll run through a bunch of ideas. Certainly other bands have used Brian Paulson because of our experiences. What is interesting is it's such an open community. If I'm working on a record I'll call Howard Bilerman in Montreal. We met Howard the first time Superchunk played in Montreal, and he's the reason we have Arcade Fire on our label. I can say, "Howard, what's the deal with this piece of gear?" The same with Brian Paulson or John Plymale — I can ask them about stuff.

Have you done production for other artists?

This band, Lori Meyers, from Spain asked me to come record their Viaje de Estudios record for them — in Granada, Spain. I felt a little bit over my head with certain things that I never really had to worry about at home — like getting a great bass sound from a bass that doesn't sound that good. I was like, "I wish Brian Paulson was here to fuckin' deal with this." At the same time, I've gotta say, largely from reading Tape Op, reading the Tape Op message board, learning stuff and accumulating gear — I can't afford to buy tons of stuff and see which I like. I have to really read about something a lot [before buying it]. Being able to bring the Distressor, the [FMR] RNP and RNC and the [UA] 2- 610 to Spain put me in a comfort zone-a few mics- the 4033 and the [Audio-Technica] Pro 37R. I didn't know what the studio had. It's some guy's studio in Granada that he built himself. [El Refugio Antiaéreo] It was built into the side of a hill. There is this door at one end of the tracking room that if you open it, it is a cave. That was their reverb. You just walk back there and put a mic at the end of it. Just being able to bring a few things that I was comfortable with really helped. It was really strange to be in this position all of a sudden, of having to explain to a band stuff that has had to be explained to us over the years, like, "You can't do another vocal take because you have ten more songs to do and you only have five hours left to do your record." — that kind of thing.

You're like, "Wait, I'm on the other side now!"

Also, the language barrier — I speak a little bit of Spanish, but having to talk to an engineer in two languages — it's hard enough in English. I had to have the guys write all the lyrics out for me in Spanish and then translate them so I had an idea of what was going on. They were trying to make an album in a week and it was their first album that they had ever done.

Have you had many other production jobs?

No, I've basically had two. I did the first Polvo album, Cor-Crane Secret, but I wasn't engineering or anything. I was just kind of there. Jerry Kee was engineering that. I think my main contribution to that was making Polvo use a tuner.

Any idea where you would do the next Superchunk record down the line?

I don't know. We went back to Brian Paulson for the last record — it's tempting to work with people we already know at this point because it's so comfortable, but at the same time there are so many cool studios and so many great engineers out there. We're also at a point where nobody really wants to go and camp out somewhere for two weeks that is not near home. Scott Solter [issue #67] lives in North Carolina now — he'd be a cool person to work with. Overdub Lane [issue #21] is a great studio and it's nearby also. John Plymale — we've worked with him a bunch and he's really easy to work with. I would love to go to Mitch Easter's studio [Fidelitorium, issue #21]. We recorded at the old Drive-In that was at his house, but I've never been to the big one.

You've just got to go everywhere!

I know — one song here, one song there. That would be really weird for us because when we do a record we're so entrenched. One thing that is common with all of the people that we've worked with is that they have patience to work in the way that we work. When we did Indoor Living at Echo Park in Bloomington with Plymale it was long days and long nights and John never wore out. John never said, "You guys are driving me crazy!" He was totally cool about it. r

www.portastatic.com www.mergerecords.com