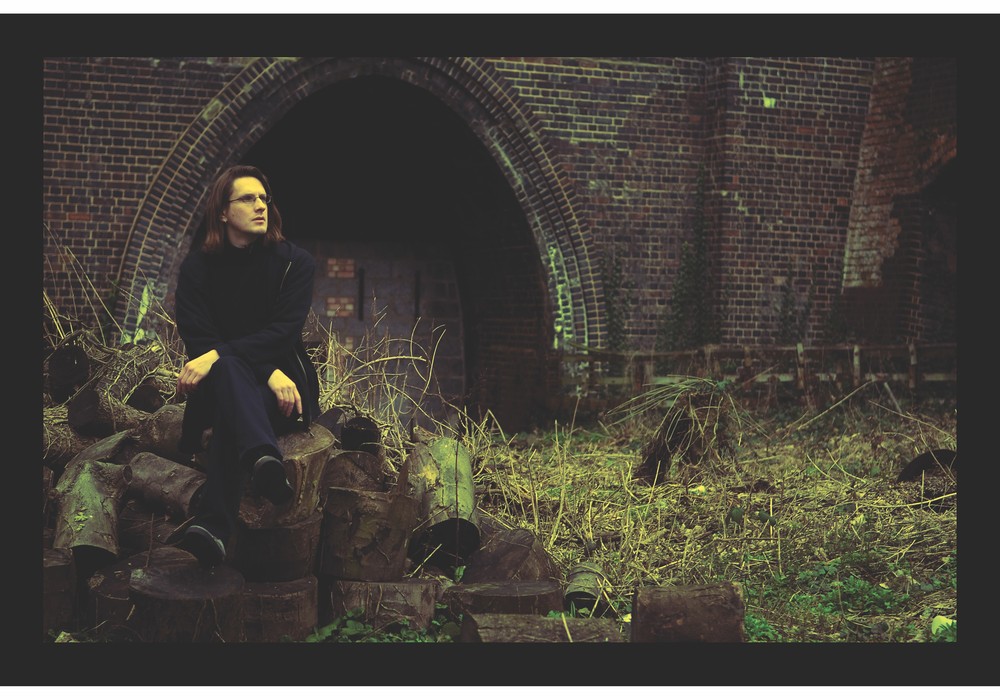

Songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, session player, engineer, producer, and solo artist Jonathan Wilson has worked with artists like Erykah Badu, Elvis Costello, Jackson Browne, Robbie Robertson, Graham Nash, and David Crosby. Jonathan's Laurel Canyon jam sessions are legendary, but these days you'll find him working at his Five Star Studios in Echo Park. Wilson's recent production credits include albums by Father John Misty, Dawes, Bonnie "Prince" Billy, and a new album by Roy Harper.

In the late '90s your band Muscadine signed with Sire Records, got a big advance, and bought recording gear with it.

Sire's Seymour Stein came to North Carolina. He was the first rock star record guy we had ever met. He let me do anything I wanted while producing the Muscadine records. I had full creative control. We bought a lot of gear with the first and second advances. Those were different times. Most of the first pieces I purchased were stolen — that was a real blow. We put it in a place called StudioEast in Charlotte, North Carolina. During the late '90s our band used that place as our headquarters. The original owner, Arthur Smith, was a celebrity in the South. Their primary business had been producing backing music for karaoke. I began engineering and playing the instruments myself on a lot the karaoke tracks that came out of there.

How did that work impact you as a musician and producer?

The process of copying those productions turned out to be a really informative experience. The guy at the studio basically figured out there was this kid — me — that was a one-man-band and could lay down all the parts on these songs. All he had to do was trade me room and board in his studio, and he had a steady supply of catalog tracks without having to employ a full band of guys. I kept an apartment up above the tracking room. It was the first real professional studio that I was trained in. I recorded versions of Motown tunes to Bon Jovi, R.E.M., Sheryl Crow, Lenny Kravitz, Jackson Browne, and the Eagles. I would routinely engineer and track whole karaoke albums. While it was somewhat embarrassing to be doing karaoke tracks 24/7 at the time, in hindsight it turned out to be one of the best learning experiences I could have ever had. I was getting deep inside all these tunes and their tones, while at the same time experimenting and pushing myself in the studio to duplicate all these sounds and playing styles.

What kind of gear did you find at StudioEast?

Old RCA BA-6A compressors, Pultecs, EMT plate reverbs, Scully tape decks, and Altec gear. I spent hours combing through all of this stuff. Those golden pieces — Neumann U 47s and Fairchilds 660s — these are the things that you dream about as a young engineer. These are the pieces of gear that are the holy grails, and usually there is a reason why. The collective consciousness remarkably picks up on the merits of the great tone; prices rise and then everyone has to have it. I was lucky, in a way, in that I was exposed to great gear very early in my career, before it had such a vintage cache. I was exposed to all types of Pultecs at StudioEast: EQP-1As, MEQs, and HLF-3Cs. I pulled a [Universal Audio] Cooper Time Cube out of the dregs of that studio. People couldn't have given a shit about a Cooper Time Cube, a [Gates] Sta-Level, or an RCA 77 mic in the 1990s in North Carolina. I remember a guy in North Carolina that used RCA 44s as doorstops in his amp repair shop.

What is your dream signal path?

A V72 preamp into a Pultec into a RCA BA-6A. The BA- 6A is the number two compressor behind a Fairchild. To my ears, those are the two compressors that actually create atmosphere and enhance and widen a tone source. The design of a Fairchild is just bonkers; it's the fastest compressor in the world! I'm very interested in [Fairchild designer] Rein Narma. The Fairchild always brings a "wow" factor to it, particularly on a vocal during a mix. If you want magical shit, unfortunately there are only a few compressors that offer that.

I think with most compressors you get something, but you lose something at the same time.

That is true. I record to tape most often, so I don't use much compression going in these days. The room I mix in a lot has two Fairchild 670s, so the stereo bus and drum bus on my mixes always sees these limiters. It helps that my tracks are fairly light in the compression department. A good tracking compressor for me would probably be a VCA compressor, like a dbx 160 or the Vertigo Sound Quad Discrete VCA compressor [VCS-2]. That's a compressor you can actually track through with without much degradation of bandwidth. I'm leaning toward the Alan Parsons school of thought these days; with little or no compression, the Studer tape deck, and real instruments played dynamically.

After Muscadine disbanded, you built a studio in Georgia?

Yeah, with my buddy, who has since passed away. He was our first drummer, way back. He struck it rich in the construction business and wanted to build a studio; I was the gear captain. We put together a good spot. It was our own private place that booked sessions through word of mouth. We focused on great instruments — we had a guitar and amp collection that was out of this world, and more vintage drums than any other studio I've been to since. The console was an MCI JH-636. We had two tape machines, an Ampex MM 1200 and an Otari MX-80.

You've been referred to as a "one-man orchestra" — a guy who can play most all of the instruments on a record. Is that how you recorded your solo album, Gentle Spirit?

Half of Gentle Spirit was performed and recorded alone, mostly engineering by myself as well, in my little bungalow studio in Laurel Canyon. It was a wood- walled and ceilinged room with Spanish tile floors. It sounded pretty good. The street noise was so extreme that on many records we used a lot of dynamic mics, like a live show. A [Shure] SM7 was often used for vocals. I had nice condenser mics, but they only got used at night when the traffic died down. There are bits of noise — horns, rain, and cars — all over the Gentle Spirit record. We would mic the Leslie speaker out in the yard, the plate reverb was in the dog cage outside, and the guitar amps were often out on the back deck. The other half of Gentle Spirit was a band that I assembled from the weekly jam sessions I was having. There was a "house band" of guys who consistently showed up to play music. These were the guys I wanted on my record. We had Andy Cabic and Otto Hauser (Vetiver), Chris Robinson and Adam MacDougall (The Black Crowes), Josh Grange (k.d. lang, Dwight Yoakum) on pedal steel and some other Laurel Canyon statesmen as well, including Barry Goldberg (The Electric Flag) and Gerald Johnson (Steve Miller Band). Gentle Spirit also has cameos from people like Johnathan Rice, my best old friend Colin "Husky" Laroque, and many other Canyon locals. I'm glad it happened the way it did. It was a wonderful time; it was genuine, and not in the least bit contrived. That's why it worked and why there has been this much interest in it. My policy was to never record any of it, oddly enough, even though it was taking place inside a recording studio.

One could get the idea that you're a tape purist. Did you do any DAW recording for this album?

Actually, a part of Gentle Spirit was done digitally. Somehow the word got out that it is "completely analog," which is not true. I don't hear a huge difference between the tracks cut to tape and the ones cut to [Apple] Logic. Some songs were transferred, as well. The musical sensibilities, the songs, and the gear are the same. There are no plug- ins or anything. That's a big part of it — keeping all the effects physical. There's a spring reverb and there's a plate at my space that we used during tracking and roughs. The mixing of that record was done at The Hangar in Sacramento by Thom Monahan, with myself and engineer Bryce Gonzales helping out. Thom used the excellent reverb selection at the Hangar extensively; there are several AKG springs and an EMT plate. The Hangar has so much amazing outboard; it's pretty insane. We had to stay focused and not patch four pieces of gear on every track! The bus compressor we used on that record was a Thermionic Culture Phoenix.

People can get lost in this equipment idea, instead of just doing things...

It's really easy to sit back and say, "I can work with anything. I can make a record on an iPad." But it's not true. I'm completely geared out. But what really works for me is to cut down the amount and keep equipment that is proven to work.

The music you record has a certain vibe to it, and it comes from you. It's not just reaching out for a 1970's palette to sound like one's heroes.

For me there's a goal to try and transcend an era. If you sound exactly like an era then, at your very best, you're just aping a sound or making a copy of something that was greater than what you're doing. That's not a goal to me. But it is a goal to take a bit from every little thing and create my own sound.

When you produce other artists, how do you approach getting the best out of them?

I do have a very strong sensibility about the integrity of each part of the band, from tuning the drums to the microphone choices. There are not a lot of preconceived things, but there are things that I feel extremely strong about. Like a [Neumann] U 47 above the drums; sometimes that's about 60 percent of my drum set. My [Fender] Princeton amp is on every album that I do. I use a lot of crystal microphones because of their extremely limited bandwidth. But I try to find a balance and not overbear a band's sound with my own thing. I coax out the performances and the personality of the singer. That's the main thing. I can't produce anybody that's trying to be a character that they're not.

When you're mixing songs that you've tracked, how do you maintain a fresh perspective?

I guess just lots of time. It's always harder for me if the process has a deadline. But on a song where I've done all the instruments, I've been doing that for so long I can almost take myself back from it and pretend it is a band with a drummer, a bass player, and everything. It helps that I'm not that attached. Sometimes it can backfire — like when all the parts are done with the same groove from the same guy's hands. That's something to be cautious of. You might lose the spark.

Nigel Godrich came to work in your studio.

He did an album [A Different Ship] there in May and June 2011 for a band called Here We Go Magic from Brooklyn. The fact that those guys came and did that was sort of a catalyst for us to pop in and build the control room. It was all in the same space before that. That can be cool, but now it's better to be able to hear things well. Now we have essentially a tiny version of Abbey Road's Studio Two, where you walk up the stairs and the control room is up above.

Nigel Godrich showed you a trick on how to mic drums without phase problems. Tell us about that.

He's big into the angles of the microphones, so that they're completely straight to each other and things aren't shifted or turned. Even the top and bottom snare mics are like [shows a horizontal figure].

Instead of facing each other...

Yeah. That turns out good, especially if you start to bring up a bunch of tom mics. We did a song a long time ago where the whole drum set was just one mic. The people that I know, producers I work with, they talk about that as a romantic idea, "We're just gonna use a few mics, like back in the day." Then, once they're done, they have kick and snare mics on. They can't stick with just one. I would be the guy that would just use one. It definitely cuts down on all the cancellations and all the problems.

Do you prefer an analog workflow?

Plug-ins and Pro Tools are just very hard to work with, for me. Every little thing takes a long time. I know most people say that it's easier. When an album is on tape, you can pop on a tape and just push up the faders and — boom — it's there. With the computer it can be brought back on the desk, but that's a big fight. I guess the point I'm saying is that when I go back to hear it, even though you can save your whole shebang, it always feels changed. I'm always making adjustments, like something about the bass drum; "Now it's gone again?"

I remember you've also used a cassette for saturation?

Yeah. There's a version of that Madonna song I did, "La Isla Bonita" [from Through The Wilderness, a Madonna tribute compilation]. I tracked that on digital and I mixed to a cassette deck and put it back to digital. That's why it's got the wow and flutter. I'll use the varispeed on a tape machine; like when I'm putting down an organ track, I'll actually pull the speed up and down. I always enjoy that, like on examples such as "While My Guitar Gently Weeps," where it goes a little bit sharp and flat, based on the machine.

What qualities are you looking for in recording equipment?

Just that it's got to have a color, that it's gonna serve a purpose, and that the construction and intention are of a certain quality and usefulness. I'm trying to find things to keep forever, not things to keep trading. There are guys I know who have had everything in the world, whether it was [AKG] C 12s or [Telefunken E LAM] 251s. "Let's split hairs for hours about Mylar versus PVC." It gets ridiculous, really. If I was an artist that went to a producer that couldn't make up his mind, and his decisions weren't strong and assured about his gear, I would be scared. You couldn't trust him. I'm trying to be conscious and to keep things within a smaller orbit. Recording to 24-track analog — and staying analog throughout the project — really helps with that.

What was your default vocal/acoustic guitar signal path for the Gentle Spirit record?

I use my trusty David Marquette [Mercury Recording Equipment Co.] racked V72s -I've had them for many years and they appear on almost every record I make. The vocal mics on Gentle Spirit were a Neumann CMV 563 with an M7 [capsule], an EV 664 and a Shure SM7. The chain would be the mic, a V72, a Manley Enhanced Pultec and a Urei 1178.

You became tight with Jackson Browne after he was handed an early copy of Gentle Spirit a few years ago.

Jackson is truly an inspiration. I'm proud to say he's a friend; he's such a special guy with an amazing set of ears in the studio, and obviously an amazing wordsmith and singer. We have worked together in the studio on some of his new material. I also got him to sing on the Dawes record [Nothing is Wrong] I mixed at his place. I'm going to ask him to sing some on my new record; I hope he is down to do it! From Jackson you see where an unwavering commitment to quality and musical values leads you. Jackson owns and runs Groove Masters, one of the finest studios in Los Angeles. It's a private studio and a world-class spot.

You co-produced the album Fear Fun for Father John Misty. What did you bring to the record?

I'll say that that record was made how I think records should be made. We explored sonically, took many chances, did not second-guess every decision, and we powered through with emphasis on being creative every step of the way. Josh Tillman came to me with some amazing songs — that was the genesis. I assembled a team: the great Keefus Ciancia on keyboards, I played most of the stringed instruments, and Josh played drums and sang. Josh is one of my best friends and that record truly was a blast to make. We were a bit like John Lennon and Harry Nilsson or James Taylor and Dennis Wilson; a couple of salty dogs making an L.A.- centric record. I can't say enough about how great the tunes are. "Hollywood Forever Cemetery Sings" is a classic. Acerbic wit and a few U 47s can't go wrong...

What do you think about the relationship of a song and its recording? How important is the quest to find your own sound to convey a certain musical message?

Extremely important, and it's the only way really to get your message to resonate with anything in the universe. When your sound and vision — whatever you want to view it as — is really you and your singular distillation, only then will it be able to contain a message of any power or distinction.

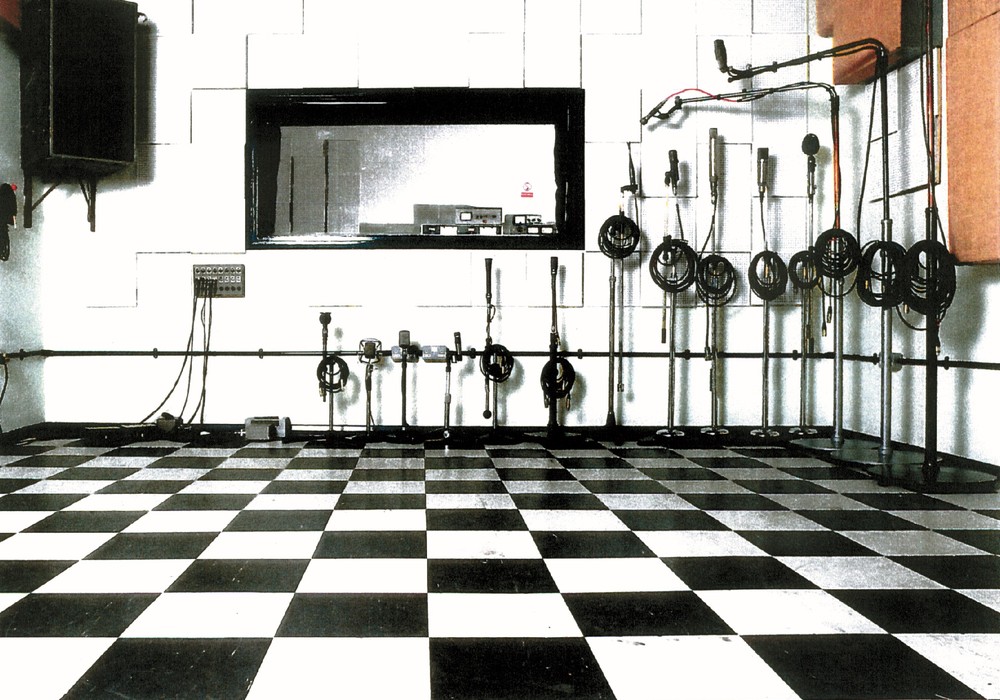

Five Star Studios Partial Gear List

Studer A80 2-inch, 24-track

Otari MX-80 2-inch, 24-track

Ampex ATR 102 mixdown deck

MCI JH-416A 24x16 console with Sage Electronics op amps

Quad Eight 6-channel mixer

Tannoy monitors with Mastering Lab Crossovers

Yamaha NS-10m monitors

Bryce Electric compressors

RCA BA-6A compressor

dbx 160

Classic Audio's APIVP25 (from kit)

Pultec EQP-1A

Hairball 1176 (from kit)

Telefunken V72

Avedis MA5

Ecoplate II Plate Reverb

Shure Mics: SM7 and SM57

Neumann Mics: U 47, U 67, U 87, KM 64, KM 84

"The Studer is Jackson Browne's machine; he laid it on me a few years ago. It was meticulously maintained by Ed Wong, who has been with Jackson for 30 years. The Otari is there as a backup now. It's like a Honda; it just runs forever. The main engineer at Five Star is Bryce Gonzales, who makes amazing tube compressors himself, so we have an array of Bryce Electric compressors." -JW