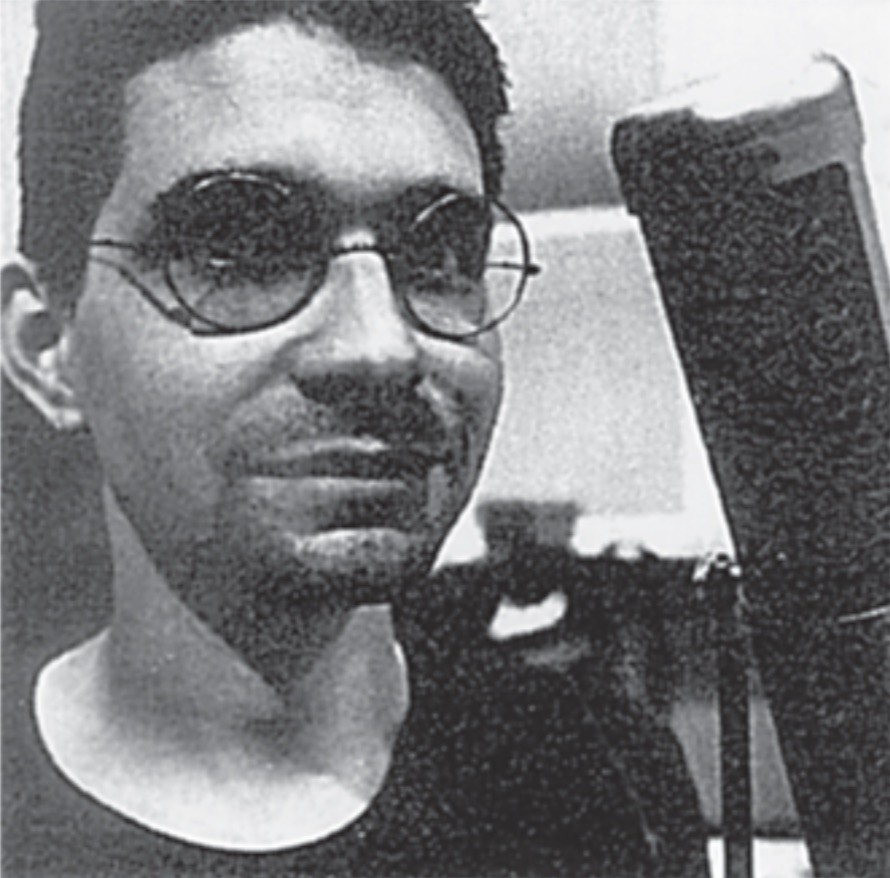

Steve Albini has become a somewhat legendary figure in the recording world these days. Our pal, John, gave us these leftovers from an interview he did with Steve recently, and it provides a basic look into what Albini is up to and all, but it's only a teaser for a future interview with Mr. Albini (if he'll let us) where I'd like to get heavy into the technical end of recording with him. For now, enjoy this intro into the mind of an engineer who will not be labeled a "producer". -LC

Going back in history a little bit, I remember reading that in your college days you would incite people to try and attack you by insulting them from behind a Plexiglas barrier.

That was one specific art project that I did. It was a piece of process sculpture. The remains of that Plexiglas screen and all the objects that were thrown at me were meant to be displayed, were meant to be shown as the result of the process, the process being taunting.

In terms of the music you create, from Big Black to the present with Shellac, would you say that confrontation and provoking people to react by raising their ire or frustrating them is a concept you've maintained.

No, not at all. I actually feel quite the opposite, that what the bands that I've been in have been about has been specific and within the band, and the outside world only enters into it really as sort of the proving grounds of the experiment. The reactions of other people are not the product of what we do. Other people's reactions are in a lot of ways immaterial. It's always satisfying if you feel like you're communicating with somebody and they're participating in what you're doing, almost on equal footing, with what the people in the band are doing. But that sort of camaraderie doesn't happen every time, and when it does happen it's an unusual, surprising and exciting event. So most of the time what we are doing is for ourselves.

With the new album, Terraform, one gets the idea of a barren landscape that is reborn, or repopulated or re-foliated to resemble Earth, or the familiar. Yet at the same time it's distinctly alien. In the same way there are elements of familiar or mainstream rock that occur on the album and yet are mutated to an extent to create new sound. Is that more or less the idea or am I just shooting blanks?

Well, we chose the name for the album on purpose. Being in a band is a construction process. You're putting together your aesthetic, you're putting together the songs, you're putting together the relationships of the people within the band and the relationship that you're going to have with the people you're playing in front of. And if you direct those decisions after a specific effect, and say, well, we wanted to end up like this, you're going to be disappointed. So all you can really do is start processes underway, like start a methodology underway and wait and see what happens. And that's sort of the modus operandi of the band on all fronts. We've got an idea of how we want to conduct ourselves and we've got an idea of what things we want to try, but the end result of that is what actual habitat we end up in, and what actual songs and sounds. What net effect do we have on the people that are in the band and the people that we play with? All of that's unknown.

I was intrigued, because when I brought the album home one of my roommates said, "Oh, the artwork reminds me of Shusei Nagaoka," who did a lot of those Electric Light Orchestra and Earth, Wind & Fire albums during the 70's, and so he was wondering if it was kind of a deliberate throwback thing or...

The choice of Chesley Bonestell is actually very specific. When I was a kid, there was a children's book called From The Earth To The Moon, which was illustrated Chesley Bonestell. It was actually illustrated using a number of paintings he had done for Collier's magazine in the 40's and 50's about what space travel would be like. The illustrations were done during a period when there hadn't even been any exploration of the upper atmosphere. It was an entirely theoretical proposition, space travel. And the thing that amazed me over time was how many insights Chesley Bonestell had just from a purely academic knowledge and from an Earth-based knowledge of what the other planets were like and what space travel would be like. It was amazing how often he was right about how things would go. And about how things would look. It's not amazing that he got some of the things wrong that he got wrong. But that blend of just this uncanny prescient quality of being able to discern how things would go, long before anyone had even postulated the ideas, paired with just a naive perception of what technology would be around, and an unavoidably naive perception of what technology would really be here, I think gives his paintings a real charm, and I don't know of anyone who's working in an equally futuristic vein at the moment. There are a lot of buzz words and catch phrases that get kicked around in popular culture and fine art, you know, the information age and technology and all that kind of nonsense. But here's a guy who imagined that space travel was possible, found out everything he could about the methodology that would probably be employed and did these incredible, meticulous illustrations of what it would be like. And he was right far more often than he was wrong. He's a really remarkable character.

What was it about the music you were creating with Shellac at the time that made you return to those images?

Really it's sort of been a long standing affection of mine, and there were some reprints of his stuff done in a couple of magazines,so I got a chance to show them to Bob and Todd and they all thought that it was apropos. You know, there's a parallel between his artwork and everybody in the band. How you can imagine how something would be and present your take on it and then you're either proven right or proven wrong, and the degree of rightness or wrongness isn't as important as that it's possible to be right or wrong. In a complex subject there may be 150 specific elements that you could analyze as being right or wrong. 149 of them you can get totally wrong. But the one that you get right, if that's something that wasn't blatant and obvious, then you've had a unique insight.

You seem to be most comfortable musically playing in trio settings. Have you had any desire to work in any wildly different configurations at some point.

Well, as it happens, I'm only really comfortable playing as part of a band, that is, a band that is a permanent embodiment of a set of ideas that everyone is committed to. I've done occasional things where I've played as a side musician for somebody else, and that's almost always as a personal favor to someone.

Have you ever considered film scoring or things like that?

Again, only to help someone out. It's not an interest of mine. People that do that sort of stuff as a profession do that very well and understand the complexities of it, understand what's required of it. And me, from a naive perspective doing it, I would make countless callous blunders, you know.

Shifting gears, how did your working relationship with Page and Plant come about and what sort of experience was it for you?

It was an enormously rewarding experience, just being in the company of people of that sort of significance, people with that kind of history behind them, you know. Definitely we got along really well and I consider them great friends and I had a fantastic time working on their record.

Was it a case of them approaching you, or was it a project you were interested in from day one and said, "I'd like to do this."

About a year ago I got a call, I actually got a fax, from their management company that said they were interested in having me work on a record, would I be free to come to England to meet them? And I replied that I was a little bit humbled by them approaching me at all, and of course something like this is an opportunity that doesn't come along very often. But my time is generally committed pretty far in advance and I wasn't able to just drop everything and fly over, but if they wanted to schedule a session where we could get to know each other and possibly even get some work done toward a record, that would be the best way to evaluate whether or not we would get along and whether or not we could do a record together. 'Cause I didn't feel comfortable strapping into an extended project of that magnitude without them being completely sold on me and without me being completely comfortable with the way they wanted to make the record. So we did a short test session in June of '97 and that went well and at that point everybody committed to doing the record in September. We started in September, and then we just carried on.

It's interesting because I seem to recall an interview in the late 80's with Robert Plant in which he professed his admiration for bands like Hüsker Dü and the Violent Femmes. Is he a person who keeps up with less mainstream music?

Well, both he and Jimmy Page are pretty much the same rabid music fans that they've always been. Robert Plant still buys, I would guess he buys ten records a week. He's not operating in a vacuum. A lot of moribund rock stars sort of hole up in their castles and never venture out into the outside world. And Robert is so full of life and so full of the experience of day to day life that that sort of lifestyle just isn't possible for him. And Jimmy Page sort of came out of his shell a few years ago and since then he's made a lot of friends and he's developed a real affection for a lot of contemporary music. Which wouldn't be expected from somebody who had such a strong legacy to stand on on his own, but they're constantly talking about this or that new record that they love or this or that band that they're crazy about. And there is also an inexhaustible archive of old material for them, that they keep discovering, like old blues stuff and old juke joint music and old ragtime. There really isn't a single genre of music that they don't have some affection for.

So, the most cynical scenario is where the cigar-chomping money guys say, "Let's get some hot young producer to update their sound," or something like that.

Well, for what it's worth, absolutely no one at the record company was involved in making the record. I remember once the album was finished and mastered, Robert was even skeptical of sending them a cassette for fear that somebody in the office would bootleg it. No, the people involved in the commercial side of the record were not involved at all in the making of the record. By and large they didn't even hear it until it was ready to be put on the shelves.

And from your point of view, you probably had the usual indie cynics going "What the hell? It must just be for a big money gig," or something like that.

Well, you know, I remain blissfully ignorant of what all the nose pickers say about me on the Internet. It really doesn't matter to me. I mean, my rationale for the way I conduct myself is, in my mind, bulletproof and people can say whatever they like about me. I honestly don't care. I know that my motives are pure and that my sympathies lie with the bands and my sympathies will always lie with the bands. You know, there are people in my position who make records for a living who want to be part of the music establishment. They want to be part of the network of people who manipulate, and make profit off manipulation of careers, and I have no interest in that. I want to make good records and I want to be in cahoots with bands who want to make the record of their dreams. That's my role in all of this.

Have you ever felt the temptation to do a full-on Phil Spector approach with a band and try to shape their sound on an album from the ground up?

It doesn't have any interest for me. None whatsoever. I feel like the few times when I have been in a position where I've had to exert sort of creative energy for a band that just, for one reason or another, couldn't get their record made otherwise, I feel like I haven't done as good of a job as when a band takes the initiative on their own and comes up with their own agenda and executes it. It hasn't happened in a long time. By and large people who approach me about making records don't do it because they want me to create the record for them and put their name on it. They want to make a record themselves and they want someone who can avoid ruining it in the process.

Have you ever taken or absorbed something from one of the bands you are recording to the extent that it follows you into the music you are creating yourself?

Well, it's part of the life experience that's embodied in everything, all the music that my band does.

I partly think it would be hard to watch somebody like Jimmy Page and just be oblivious...

Well, I'm not much on imitation, but I can be inspired by an attitude quite comfortably without wanting to ape the moves that somebody else makes. And if I can be as full of life in my 50's as Jimmy Page and Robert Plant are, then I'll feel like I've really accomplished something.

There must have been some good exchanges, because the history of Led Zeppelin is always produced by Jimmy Page...

To his credit, Jimmy Page has grown a lot as a person. I think that when he was young and headstrong he wanted to be the auteur of everything that he was involved in. And you can't fault the results. You know, you can't criticize just the impeccable, consistent quality of the stuff that Led Zeppelin did. And that's stuff that was recorded under the most ridiculous variety of circumstances in the most extreme conditions. Everything from recording in a barn or in a castle to recording in state-of-the-art studios. Everything from the highest to the lowest technical standards, and it all comes out sounding consistently good. You really can't fault the results. And so his working method for the time validated itself in the results. And his working method now is much more of a collaborative process with Robert because they've got a complete spectrum of things going on in their lives. You know, they've both got intensive family obligations and they've both got quite rich personal lives. So to expect them to drop all of that and start behaving like they were adrenaline-charged and chemically-charged teenagers I think is unrealistic. And I also don't necessarily think it would make for a stable working relationship, because Robert's been on his own for eight or ten years and doing quite well. He's quite comfortable as a solo artist, and I think it took a lot of personal strength... personal growth, on both their parts, to be collaborative again.

Have you done any recording and engineering work in the electronica or dance music field?

Well, I work with a lot of experimental artists who incorporate that sort of stuff, but the genre that's referred to as electronica, which is basically just another variation of dance music that makes no pretenses about having an organic origination, I really haven't participated in that just because I don't have any feel for dance music. I don't understand it, I don't know why people make music like that, it has no intrinsic appeal to me. And if I tried to work on it I would probably do a bad job. I think there are people who understand that music and who love it and for whom it is a part of their soul, you know, and those people will do a much better job of it than I would, so there's no reason for me to dabble in it and make a bunch of lousy records in that genre.

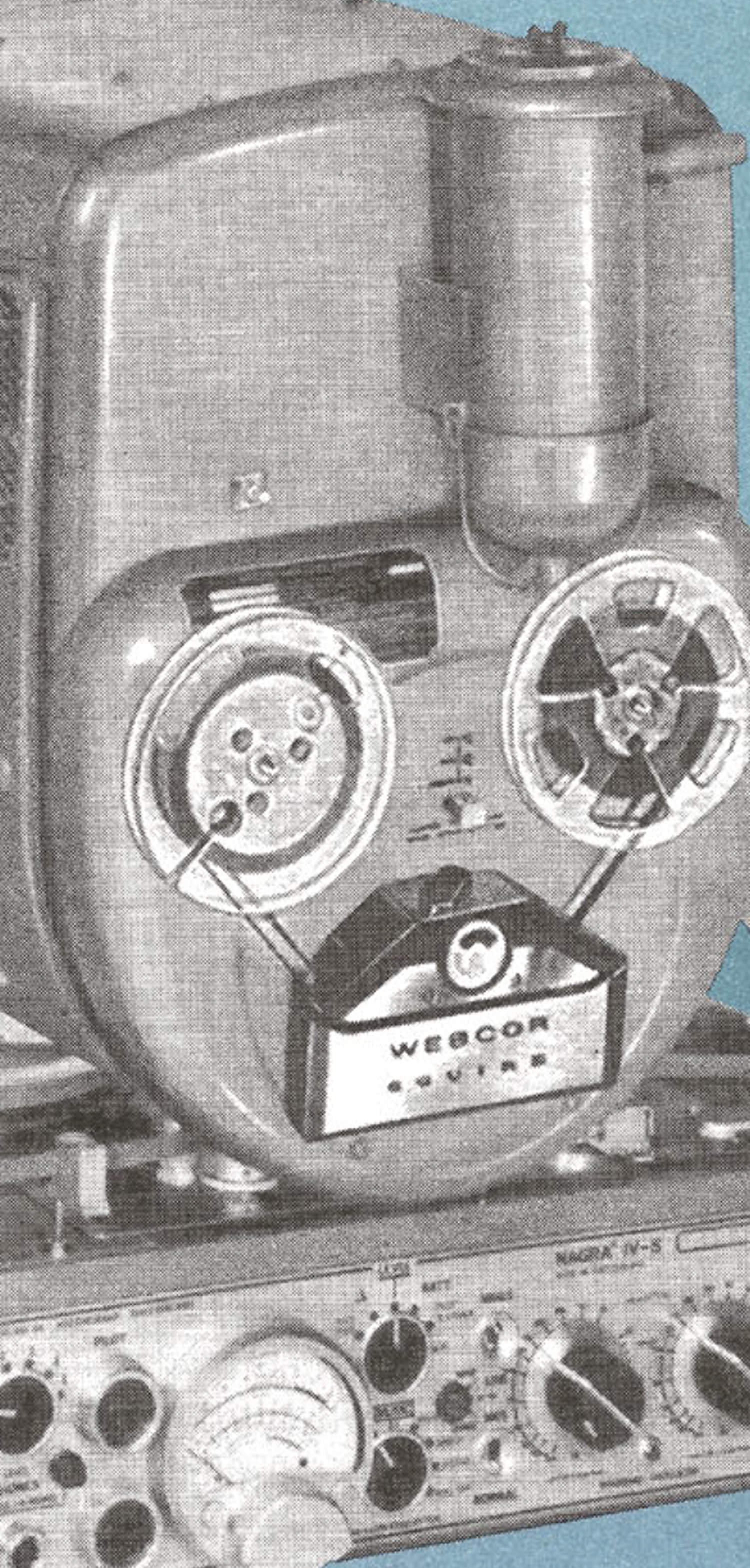

How concerned or dedicated to state-of-the-art technology are you? Do you work with vintage gear?

I like to work with good equipment, and the construction standards and the sound quality standards have not improved in the last 20 years, with a very few exceptions. So I tend to use a lot of older equipment. Not because I'm going after any sort of a retro vibe or a vintage sound, but just because that's the best equipment that's ever been made for a lot of purposes. Like a lot of microphones that were made 30 or 40 years ago are the ideal transducers. They're perfect for their chosen applications. So there's no reason to fiddle around with a bunch of new, cutting-edge nonsense if it doesn't do the job as well. The other side of the same coin, though, is that there are some things that are better pieces of equipment now than were available 20 years ago. And using them means using the best and that appeals to me. Specifically, the last generation of analog tape machines that were designed incorporated utility functions, utility features and are of a general sound quality which hasn't been duplicated and hasn't been surpassed by anything since. So, given my choice, I would work on technically sophisticated analog recording equipment.

On the evolutionary time line of music can you see anything big coming next, or will music for the foreseeable future continue to fragment into smaller niches?

Well, one thing that's happened on a cultural and on a musical level in the last couple years is that the mainstream record companies and the mainstream music industry has pretty much given up on rock music. And that, to me, is a great development, from a cultural and aesthetic standpoint, because it removed the patina of business from what should be a purely creative enterprise. And now people that are devoted to making, for lack of a better term, personal or experimental rock music, there is now no hint of commercial enterprise to it and I think that's a very freeing development. On the other hand, financially it's been very, very hard, because anyone whose livelihood depends on making records is going to be affected by the trend in the industry away from just the sort of blind infusion of money that took place in the 90's.

So you pretty much see the whole indie integrity vs. corp. contamination debate as a moot point.

Well, at the moment the mainstream record labels and the mainstream music business are not interested in anything of substance. They're not interested in quality music anymore. It's back to the state of affairs that it was in the late 70's and early 80's where the records that are on the radio are of a totally different stripe from the records I would listen to at home. Whereas, in the 90's, there was some crossover in that, between the two. And at the moment there's a much broader variety of sound, there's a much wider palate being explored in the underground than there was for a few years in the mid to late 90's. You know, almost every band fit into one of a few specific categories, even within the underground, and that's not the case anymore. Now the eggshell's busted pretty much wide-open and people are working on a much smaller scale but are making much more personal music, making music that appeals to a smaller audience. And the people that are doing it are doing it because it means something to them, and as a consequence of that they have to make themselves content with the scale that they're working on. And I think that culturally that's a great development.

So in a sense it's as if we removed big money contracts from pro sports and said, "Well, anybody who still likes to play basketball can, you just won't make 12 million dollars a year."

It's a totally different perspective, I think. I mean there's no question that basketball is played at a higher level of expertise now than it was 20 years ago, but with the exception of the Chicago Bulls, there really aren't any dynasties anymore, you know. There aren't any teams that can hold their roster, there aren't any teams that stay intact for five or ten years where players can really develop a relationship with a coach and a group of teammates over a long-term period. Baseball has been most affected by that trend. Since the onset of free agency the greatness of the sport has probably been attenuated, although the players themselves are doubtlessly doing better.

In general how do your recording jobs materialize? Do they break down along a sliding scale from major label bands to more of pro bono thing for indie bands?

I would say 99 percent of the work that I do is for bands in the underground. That is, bands that have no financial backing and have no business interest involved in their records. On average over the last 10 years it's been about one or two records a year that I'll work on, out of 50 to 100, that have any affiliation with a larger corporate entity. There are people in my position who work almost exclusively with big label bands because it allows them to make one or two records a year and make a comfortable living. I'm really not interested in making a living. I'm interested in making myself available to a broader spectrum of people and making myself available as part of a community of people who make music and make records as a creative output and as sort of one of the bones in the backbone of their existence. People that I work with, in general, are making music because it means a lot to them. It is their life's work and that's what they do as their creative expression, and I feel better about being a participant in that, in both a cultural sense and on a personal level, I feel better about doing that than I would about making commodity music which would make me rich or, you know, would make me a player in the music business. I have no interest in being part of the music business. My interests are exclusively to be part of a community of people who are creative and intelligent and expressing themselves uniquely. Those people and that way of doing things is what I hold dear. Being a part of the business is of no interest to me.