Vintage King recently celebrated their 30 year anniversary. Like most things, there is a story behind what has now become a fantastic retailer of both vintage and modern recording equipment. I caught up with founder Michael Nehra on a Zoom call and asked him to tell me the story of Vintage King’s humble beginning. Transcript edited for context and clarity.

-GS

Michael Nehra:

“When I was 17 or 18, I built a 4-track recording studio in my parents' basement and was going to recording school at a local studio. I was always fascinated by production and recording gear. Back then, you walked in and there was a 24-track tape machine. No Pro Tools. I was just mind-blown about compressors, equalizers, microphones, and the art of making records. So, I tried to replicate a commercial studio in my own humble way with a 4-track. I had some [Shure] SM57s, a TEAC 3340, JBL monitors, and I made a little control room. I started recording local bands and learned the art of recording, applying what I learned in those recording classes. My younger brother, Andrew, played bass, and I played guitar; and we'd produce stuff in the basement. Eventually, we moved up to a 16-track Fostex 1/2-inch machine, and we were making some pretty good sounding recordings with that. We also had an old Allen & Heath board. But I was a total gear junkie, production junkie, and engineer. We met this guy, Al Sutton – a local guy from Detroit that's getting pretty well known (Acme Audio, Greta Van Fleet) – and we partnered up with him. It was already White Room Studios in my parents' basement, and we partnered with Al and moved White Room to downtown Detroit. We rented a 6,000 square foot space in a shitty neighborhood, but the rent was a thousand bucks a month! We had the whole floor and killer sounding rooms. It had been an old dance studio, with wood floors and it had a beautiful ambience.

At this time, I was playing in bands and going to studios in New York, L.A., Miami, and recording with various engineers and producers. People like Chris Lord Alge to Ed Stasium. They were really talented, and I was learning a ton from watching them do their craft. And seeing and working in these killer rooms: Power Station, Criteria Studios, Record Plant. The best of the best. It further enhanced my junkie-ness for this whole process. Moving forward to the early '90s, my brother and I found this blind singer named Robert Bradley on the street and formed this group called Robert Bradley's Blackwater Surprise. He was busking for money on the street at the time – unbelievable voice. At this point we had an API console in the studio, one Pultec [EQ], one Neumann U 47 [mic], a Teletronix LA-2A [compressor] – killer gear, but pretty simple. We recorded him, got him signed to RCA Records. This guy was so amazing.

And so, it was around this time we started Vintage King. An artist we were working with at the studio came in and said he had a gig in London and asked if we wanted to come along. The exchange rate was such that you could buy gear almost half off of what it would be in the States. My dad lent me a credit card, I had a credit card, and my brother did as well so we had $8,000 worth of credit. While there, I looked in the trade magazines, went around to different places, bought $8000 of gear, and brought it back. I had various microphones, some cool vintage gear – whatever I could scrape up – and we brought it home in duffel bags. My brother wanted to sell it all and make the money, and I'm like, "No, man. We got to keep all this. Like, we've got to enhance the studio!” So, we agreed, we'll keep half and sell half.

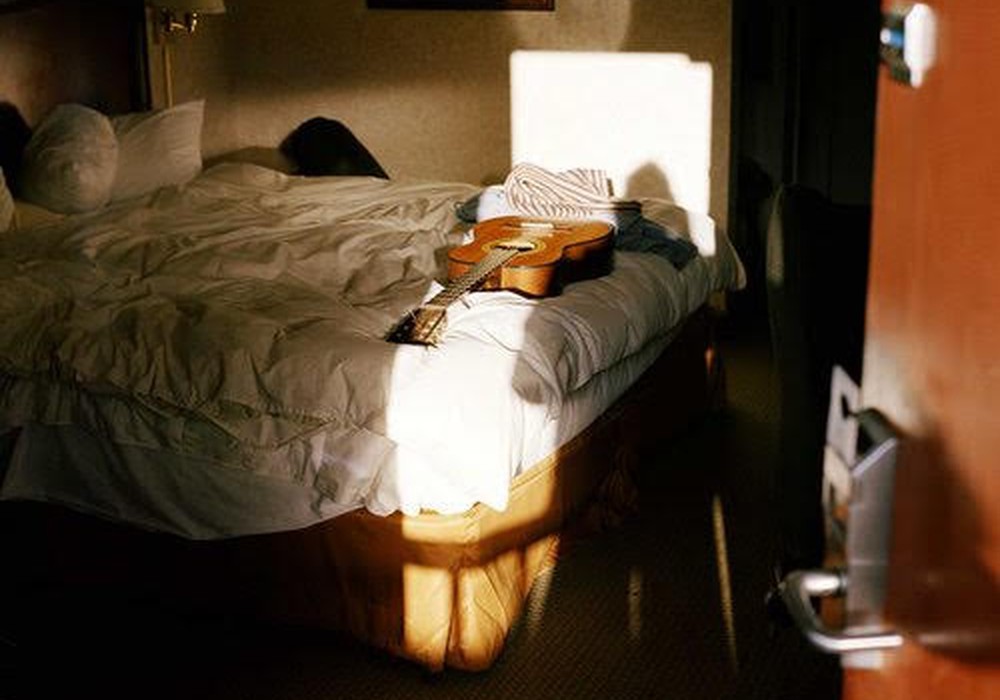

We kept doing that over and over and we started to accumulate some great gear in the studio through the process of growing Vintage King. The people we bought from would keep calling us because I paid them immediately. They said, "Do you want this?" I'd say, "Yeah, I'll pay tomorrow," and I sent the money. We were credible and the exchange was in our favor still. We kept buying tons of Neve gear, EMI gear; all this great European stuff for the most part, and a lot of American gear was flowing this way back again because of the exchange rate. The business just evolved on credit cards. We had no bank loan to do this. We kept building it, and the profit we kept bankrolling our own business. Of course, we’re doing this all while we're in this band and on tour. We got on the H.O.R.D.E. tour, we were touring with The Allman Brothers, Dave Matthews Band – opening up for these various artists in that hippie kind of vibe. Meantime, we're doing this gear business from payphones, just hustling between gas stops. We would stop, and I'd call as many customers as I could. The band would get pissed off and say, "We've got to go!"

I didn't know we were starting Vintage King; we didn't even have a name then. We would take out ads in the back of Mix [Magazine], a little 1-inch ad for the gear that we would buy, and we'd service it and sell it. Which leads to the point: Our whole thing with Vintage King is we service what we sell; we put a year warranty on used gear, whether it's a Fairchild, LA-2A, Pultec, or any of the vintage or used gear. As we grew this, we hired technicians to service everything that came through the doors. So that was a big deal to us and was the bottom line basis for building Vintage King. When we started out, my brother and I were the only employees. Then we added a shipping guy, a technician, and it evolved like that as any business would. We didn't know exactly where we were going, but I knew one thing: I could make a living doing this as opposed to the struggle in the studio and the struggle being a musician. We got to see the coolest gear on the planet all come through our doors, which was amazing. Back in the late '90s and early 2000s our ambitions were to grow this but still to make records at the same time. As an engineer-producer, I wanted to experience, what does a [Neumann] KM56 sound like? Where can I use that? What is a [Telefunken] ELA M [251 microphone]? I'd heard of all these great models, but I wanted to be sure. We got them in our door to sell them, but I got to use them before we sold them. Sometimes we'd hang on to them for a while. At one point, we'd have three Fairchilds in a rack, when they were actually obtainable! Back then, they were still expensive, but they were not $150,000! They were $20,000, which was a lot of money. We got to hear almost every weird piece of gear that you could obtain. Like the Decca compressors, those cool, square mastering compressors that were in the mastering consoles. I always read that Daniel Lanois [Tape Op #37, #127] and Peter Gabriel loved them, and each had a pair. I thought their recordings sounded pretty good, so I was like, "I've got to find a pair of those!” It took me a while, but I was super good friends with Mark [Thompson] at Funky Junk [in the UK]. When he got a pair he said, "Give me seven hundred bucks for the pair." Now they sell for $30,000 for the pair! I had them for 20 years.

We would get people calling us offering us a lot of EMI gear for $400,000. We had to buy all of it or none of it and had to come up with a cash within a week's time. At that point we had a bank backing us, and we made a deal to buy. It must have been about four large format vintage Neve [mixing consoles] and three EMI mastering consoles. In five by five by five, heavy cardboard boxes stacked with EMI mastering modules. The real expensive four-band EQs, compressors, and the midrange modules from those consoles. There were dozens of each stacked, with no padding – just piled on each other. I opened the case, and I was like, "Okay. We paid $400,000 for all this shit." The consoles came in, and they always needed work and TLC. But to see this box of rare EMI electronics with no padding! We tested every one, and every one of them worked. There were some mind-blowing purchases like that.

Helios was a huge thing for me. A lot of the great British studios had Helios, so it was always fascinating to score a Helios console. We've bought and sold many. At this point things were really kind of churning. It was early 2000s, and I was moving out of the studio business and more into this, because it was taking my time. Not that I didn't love the studio, but I'd been in it for a long time, been in bands and had various degrees of success, but this was a new thing I was chasing. This was, of course, before the internet took hold. There was no Reverb.com and eBay wasn't evolved yet in terms of selling recording gear. All these deals came through people like ourselves, Fletcher at Mercenary, Dan Alexander, and people like that. But nonetheless, we kept scoring some amazing packages. I might get a shipment of 15 tube mics at a time that had all Neumann U 47s, AKG C12s, and AKG C24s. Premium, you know? You don't get that anymore. Now, we still buy and sell all that, but we'll get one or two at a time. We might get a collection here or there once every other year or something, but back then it was continual. It was massive amounts. When these deals came up and studios were closing, we had to come up with the cash. We couldn't borrow anything when we started, but over a period of years we started to get a $25,000 line of credit, then 50 then it got up to 100. At one point, we would go buy packages for $700,000 worth of a studio closeout, and the bank would write a letter: "We back them.” It took a long time to get to that, ten years to have that backing, and that was important.

There's a lot of history in between all that, but it started with a couple guys that were musicians and loved the process of recording. It was really a path to own the equipment in our studio. That was our ambition, and then it became a business out of, "Okay, we've got too much gear. We can't keep all this!” And the timing was right. The market's much different, and the gear is way more expensive now. When we first started, one of my first scores, I bought ten Neve 1073 modules for $700 each. I sold them for $950 each. Yeah, I made $250 bucks a module. I called all my engineer friends. I said, "Hey, you want a pair? I'm getting these from guy in Canada." I sold them all in a few phone calls. I serviced them myself. I wasn't a hardcore tech, but I could see if the caps were bad, and I know how to wire the connectors and make harnesses and all that. If they needed proper servicing I would take them to a tech. But I'd sell them serviced, and that was our gig.

It started out of the back of a van and a tour bus, and just rolling around. Everybody was getting high in the van, but I was on the phone making deals on recording consoles. It's been a great journey.”