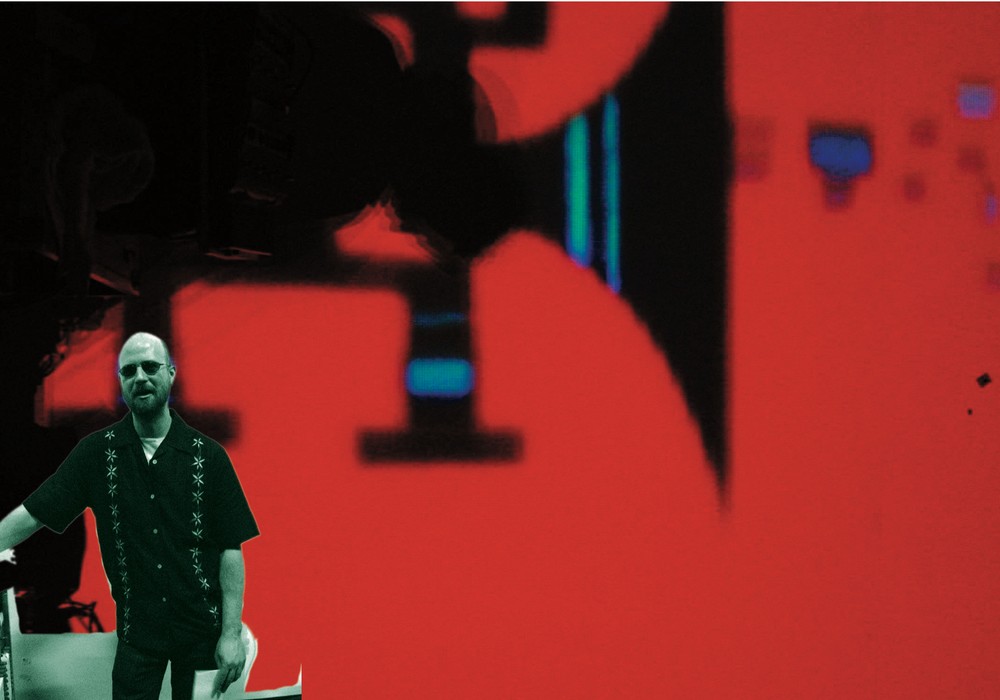

You may have seen Doug Williams' name on recording forums, listing frequency response curves and specs on obscure preamps, limiters and transformers. Maybe you have used one of his posted hand-drawn schematics to repair an old amp. His real love is tube audio gear from the 1930s and '40s, and his ten-year-old studio, ElectroMagnetic Radiation Recorders (emrr) in Winston-Salem, North Carolina is floor to ceiling with ancient recording equipment. Recently Doug and emrr have been getting some notice for the recordings and production he has done with the bluegrass/ punk/folk-influenced Avett Brothers. The band is playing sold out shows all over the country, they have a new deal with American Recordings/ Columbia records and are currently recording their major label debut album with legendary producer Rick Rubin. Doug Williams attributes much of The Avett Brothers' success to their work ethic, endless touring and their ability to connect with their audience through their lyrics — plus the sheer intensity of their performances. His work with the band spans nine albums, including studio and location recordings and several solo projects with individual members. Their most recently released EP, The Second Gleam, was recorded, mixed and co-produced by Doug and released in the summer of 2008.

Is this the first album that has cracked the Billboard Hot 100 that you've done?

Yes it is.

Do you do anything different when recording a popular group like The Avett Brothers?

I try not to. [laughs] Hopefully a popular group means that they have some income to work with, so there is less fear about time and budget, which allows you more freedom to make decisions and have discussions about what you're doing. That's the biggest difference.

How did you get hooked up with The Avett Brothers?

The first thing I did with them was the Nemo [their former group] record, which was a punk/metal record in a way. I knew the guy producing that record through some other people in Charlotte, and he suggested they come to me. I have no idea why.

About what year was that?

I think that was '99 or 2000.

Had you worked with bands that were into bluegrass or folk before?

I had done a few recordings in that area, but I didn't have a track record in that type of music. I have mostly done rock records, which is why I got the Nemo gig.

What's the real difference between recording a full-on rock band or an acoustic band as far as engineering goes?

I don't know. I am probably dodging the engineering question, but it seems like it's as much about getting the right concept of the way the sound fills the space, whatever the space is and how to capture that. In a way it's really the same process you have to deal with when recording a loud band.

What special recording techniques did you use when recording the Avett's?

Scott Avett has a bullhorn, mid-frequency boosted voice with not much highs or lows in it at all. You can't even take 2 dB out at 1 kHz on his voice without it sounding hollow, because that's almost all he puts out.

Which is very cool because it cuts through a mix.

Yeah, but it also means it's a big pain in your ass. If you didn't mic it right it will step all over everything else. Even though they'll be doing very intimate acoustic songs with lots of space at times, they still have this punk rock screamer performance dynamic in the way

they do it. You've got to manage to capture all this really wild dynamic range, and control it without having everything explode. You have to leave insane amounts of headroom in all the gear's levels, because there is going to be a peak somewhere that's 20 dB hotter than anything else. If you try to get "hot" levels on them you will have every take destroyed by something. You really have to put on this nuclear blast shield approach to dealing with recording them. It takes a containment method more than a capture method.

Have these guys actually blown up your levels before to where you couldn't use a take?

I don't think I've ever been stuck with that, but a few songs of theirs have glaring technical problems in them that no one else would probably hear. There's at least one of my favorite songs that was all cut live in the same room, and the banjo is louder in the vocal mic than the vocals are. You have to live with the banjo being too loud. That's half the battle with doing anybody's record — it's not, "Did we get it perfectly and can we redo it?" Sometimes you have to make it work.

If you get a really great take, but there's something like that where an instrument gets too loud, do they listen back to it and want to fix it?

Generally not. They're more concerned with the performance. If they feel like the performance and the vibe is right then that's the overriding factor. That's how it should be. Most of the great recordings in history have not been terribly well recorded, and there's something wrong, but that didn't stop anybody from putting it out. Put on any Sonics record. They wouldn't play it on the radio because it was too raw, but it's the greatest thing on earth.

What's the typical setup for recording The Avett Brothers, for example on The Second Gleam record, which is just the two brothers?

My interpretation is that they have an approach that is very much like Dylan doing a record. They want to walk in and have you capture reality in the most pleasing possible way. They don't want to dwell on it and they don't want to analyze it. They want to get it down and hear a playback and say "yes" or "no." If they say "no," then they have no problem accepting that and coming back in and doing it again from the top. The acoustic record's like that — just the two of them. They basically sit six or seven feet apart in the same room and you try to get it all and have as much isolation as you can. There's no real ability to change things later, only the ability to add things. They'll do 15 to 20 takes of something until they're happy with the performance. They would rather do that than try to tweak little pieces of each part.

If one of them hits a bad string they don't go back and patch that?

They will if it's something that is fixable. You can put on their records and find obvious bad notes that they were okay with leaving, because it was a minor flaw in something that had otherwise met their expectations.

I noticed that you were listed as co- producer along with the band on The Second Gleam record. What's really different to you about being a producer on something like this?

Producer is a term a lot of people just don't get. There are so many aspects to the creative process if you are working with somebody on a project you are producing it together to some degree. You have the other, old school extreme, where you have the person who comes in that cracks the whip and makes the artist rewrite the songs, fires band members and changes the keys of songs. I've been on sessions like that, but that's not the kind of thing I do. I'm not going to help somebody rewrite a song unless they really ask, and then it's still not something I'm necessarily comfortable with doing.

It's their vision, so it's my job to serve their vision. If I think there's a better way to serve the song than the way it's going then I will suggest it, but I'm not going to beat it out of them. All the records I have done with them — and really most anybody else — it's really more of a co-production situation where there's going to be a creative conversation about whether the sound and the feel is going in a direction the artist is happy with.

How hard is it to be producer and engineer? Would it be easier for you to sit back and just produce?

It is harder. If you're having a conversation about musical aspects and conceptual aspects then you're flipping between sides of your brain, and it can be really exhausting. The few sessions that I've had where an outside producer has come in here were much easier. He cracked the whip on the band, and really all I did was engineer and whatever else he told me to do. I've had 15-hour sessions like that that were far easier than a single six-hour day where I had to do everything.

How do you know when you have a great take? Is it something you feel? Or is it something everybody knows right away?

You almost always feel it. There's almost always some kind of hair standing on end. You don't know when it's going to come.

Magic seems to happen with the Avetts.

That's true with any artists that have really dug into what they're doing and attacked it from all angles. The more you do that, the more of a channel you become for that magic to be able to come out. If you're working at it all the time, then it's more likely when that does happen you will handle it correctly and not screw it up. It's the same way with the recording aspect of it.

The Avett Brothers are going to Rick Rubin now to record a whole new album. Does Rick call you up and ask for any help recording Scott's voice?

[laughs] He hasn't so far, so I assume he has good people on that.

What do you end up using on Scott's vocal?

I almost always end up with a ribbon mic on his vocal. In a way you can almost always have the mic further away than with a lot of people, because his voice is so cutting and he does have a large dynamic range. You could almost call him an old style shouter singer. He could successfully fill a thousand seat venue without a PA just fine. Most of their vocals on The Second Gleam were recorded on [Cascade] Fat Head mics that have the Lundahl transformer upgrade. There were some things we did on a RCA 44B.

What was the preamp and the limiter?

The preamps on those guys are generally late 1940's Gates SA-94 octal tube preamps. It's what I plugged in that day — it sounded okay and I went with it.

No limiter when you're tracking?

There is a tracking limiter on their vocals — a Manley-built Langevin Electro-Optical Limiter. In a lot of cases it's not doing anything. It's there to catch the really insane peaks. At the mix stage they end up going back through something else again to really fine tune it. It really depends on the songs. Scott's vocal on a lot of this record is through the 1938 Collins Radio Company 26C-2 limiter, solely for the fact that it added an extra smoothness. Because of background bleed and the shouter aspect of the voice, there is also multiband compression happening in the computer before it hits the outboard compressor.

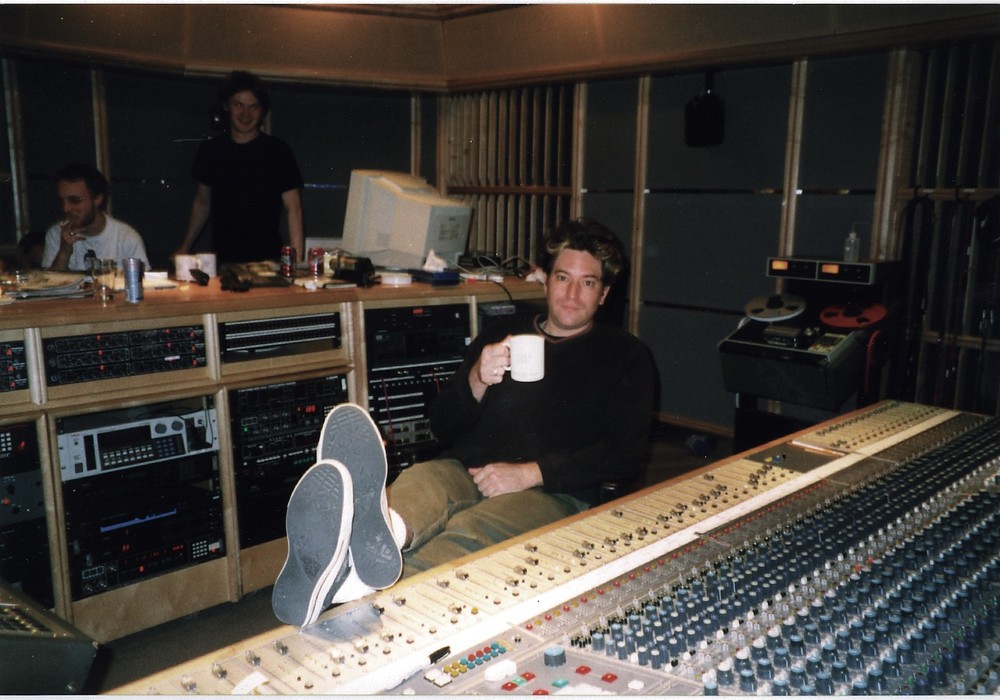

Did you mix the record "in the box"?

It's a hybrid approach. In this case the computer faders were at zero, so I was using the analog console faders for the individual levels on the mix. I was using a degree of outboard analog processing, but there's also software EQ and compression on various channels. It's a little of both.

Is it true you actually mixed it to an Edison cylinder?

I have mixed things to a wire recorder before that have ended up on records. That's an option that can whipped out if need be. I haven't fired up the Edison cylinder recorder yet, but it's waiting for the day.

I have honestly seen Scott Avett break at least 20 banjo strings during a live set.

I don't think I've ever seen Scott break a string in the studio. They maybe did on some of the earliest stuff I did with them, but for what I have been doing with them lately that stage performance aspect has separated from the studio aspect. They've learned how to approach studio work versus live work.

What mics do you use on the banjo?

A lot of times I end up using a Beyer M130, which is the figure-eight ribbon mic, usually about a foot away from the banjo. They move around a lot.

How about mics on the acoustic guitar?

I really like the DPA 4060 lavalier mics. Sometimes I'll end up using an Oktava MK-012 with the omni capsule on it — more of a Ziggy Stardust sound right off the bat.

What mic did you use for recording the piano?

That's the RCA 44 or the DPA taped inside the piano — sort of a PZM approach.

What do you use on upright bass?

A lot of times I end up using the MK-012 in omni, six to ten inches off the bridge.

Is Bob [Crawford] playing bass in the same room with the guitar and banjo when you record?

During the Mignonette record they were all in the same room and I had baffles between all of them. The bass was off to the side, but they were all relatively close together.

If there was a bad note you couldn't overdub a part?

You could replace most parts.

What about the percussion parts?

Most all of their percussion is recorded after the initial tracks

are laid down. Their original live stage set up was one brother playing hi-hat and snare drum while also playing guitar, and the other playing a kick drum while playing banjo. There have not been too many times we have tried to capture all of that at the same time.

What is their mixing process like?

They don't want to be involved in the mixing anymore. I kick out mixes to them for approval.

You send them MP3s?

Yeah. A lot of bands I have worked with in the past few years prefer that.

I have to ask what's in the water in Winston- Salem? You actually have some pretty well known engineers coming out of this not very big city. You've got Chris Stamey, Gene Holder and Mitch Easter [issue #21] to name a few.

I think there is an underdog factor in certain towns that makes people more driven to do something. If you're in a place like Winston-Salem, you've got a place like Chapel Hill down the road to look at. You've got Athens further

down a different road and might wish you were involved in that scene, but you're not because it's too far away. You either move there or you start doing something here.

Well is there any support network around here with people that are into recording?

Yes and no. I'm sure it's like a lot of places — there are all kinds of recording guys here that I don't know and we never cross paths. There are others that I do cross paths with and have done things with.

You don't go to the secret recording society meetings and drink beer?

No. There should be something like that!

The real question is, did you steal all of Mitch Easter's recording techniques?

You know, he was a great part of my educational process. The first band I was in that put a record out, The Gathering, recorded with Mitch at his Drive-In Studio. We worked on a second record with him too that was never released, but at that point he was willing to throw me the keys at times and let me come in after hours to do rough mixes of the stuff so that he wouldn't have to.

I think Mitch is a visionary that opened doors for other people around here in a way that maybe he never really knew about.

Yeah absolutely. I took recording classes not to become an engineer, but because I wanted to be able to pre-produce. At the time, going to his place was a very expensive proposition and I wanted to be able to maximize that. We actually walked into his place with track sheets. He thought that was the most hilarious thing ever. But to me it was like, "Oh really? Other people don't do this?" It turns out there was no way we could have done the record we did in the time it took if we hadn't done so.

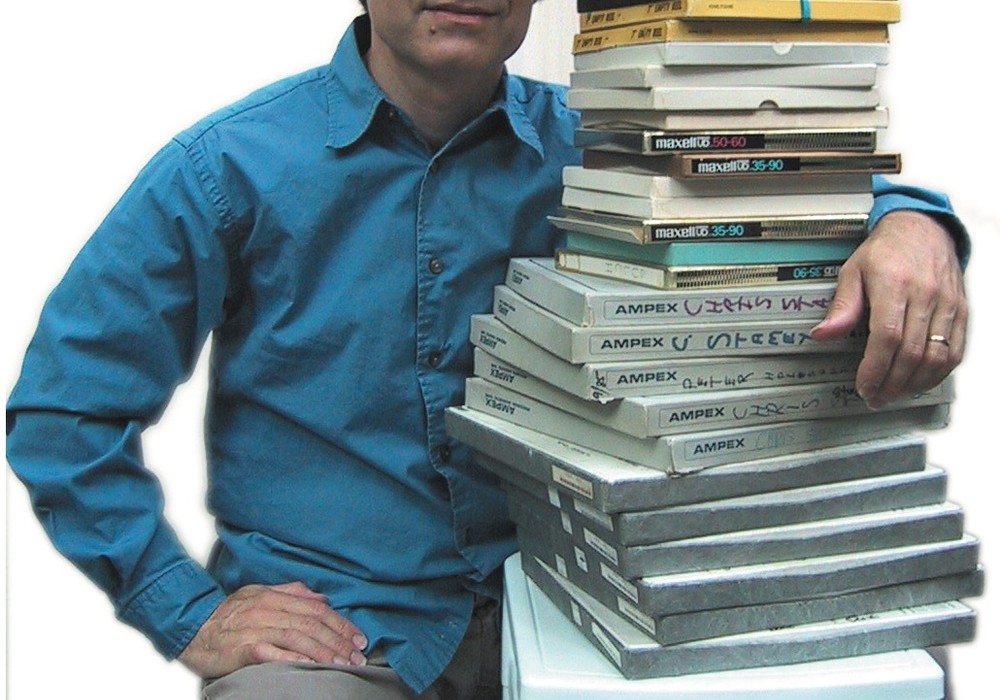

There's all this ancient recording gear in your recording studio. Does all of it work?

Most of it works, or it will work when I'm done with it.

Do you modify most of it?

It depends. The old tube limiters were for broadcast use and have limited controls, so I end up making them do more than they were originally intended to do. Usually I add attack, threshold and ratio controls.

What was in this building before?

It was originally a 1920's wood frame house. I think it's been an antique store, a dental lab and a bar and grill. A few years ago an older couple walked through the front door and got all the way in to the middle of the tracking room during a session, looked very confused and asked where the bar was. They said they were supposed to meet some old friends here, and that like 30 years ago they used to come down here all the time.

Do you have that on tape?

Probably somewhere! www.emrrecorders.com, 336.785.0454

David Seward is the recording engineer at Rock House Records in Greensboro, NC

and runs Angel Food Music, www.angelfoodmusic.com, dseward@mindspring.com

Woodie Anderson did the photos, woodie@deftgurl.com