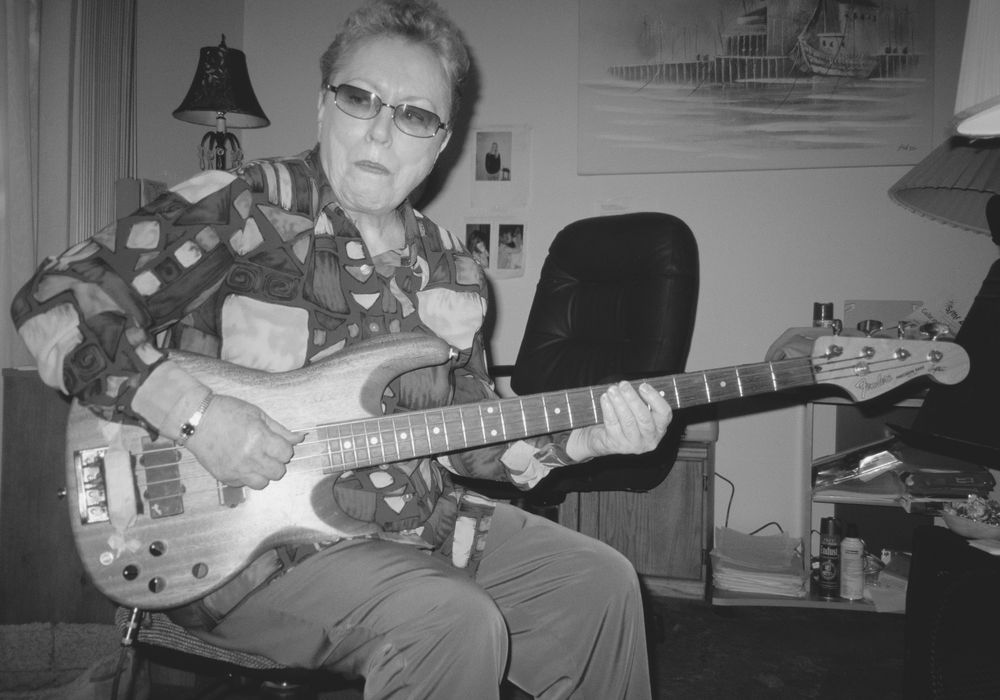

Merrill Garbus is the founder and central figure of tUnE-yArDs, an extraordinary band that I have had the honor of doing sound for over the past year, traveling in support of their fantastic album w h o k i l l. Her music, some of which is co-written with bassist Nate Brenner, is fiercely dynamic and unapologetically raw, while showing off a vast number of skills: her unique and arresting voice, her prowess at live percussion looping, and her bad-ass ukulele chops. Her first record, BiRd-BrAiNs, came out in 2009, and ever since then she's been growing, both in popularity and also as a musician and recordist.

When you listen to the records you love, what percentage of your attention is captured by the songs themselves vs. the record production?

I think that for the longest time I didn't think about the production of a record at all, because it just wasn't my framework. And now, that I listen for those things, I think it's a little bit of both. On Paul Simon's Rhythm of the Saints, the production is like all of it, I think. I mean, sure, the songs are awesome — it's Paul Simon's songwriting — but it's the vast space that the sound takes up. But then, his earlier albums, which are mostly just him and guitar, I think it's the songs that captivated me. It's funny, because I always get that question about lyrics versus music, what captivates you first, the music or the lyrics, and my answer is always the music, because I never know the words to anything unless I know the sounds of the words. I feel like it's hard for me to know percentage-wise, but I have the feeling that production is huger than I ever realized, even when it's the songwriters themselves; even if it's not, you know, the "producer," the Phil Spector character in the room that's influencing the sound, I think it's the sound that's captivating, that's creating this world. I think that's been really important for me, is the sense that whatever art you're working on, it is a world in and of itself. If that's within a song or within an album, those are the moments that it feels really alive — like anything could happen in there — because it's clearly defined. I think that's what production is. There are parts of songwriting where that craft is involved, but in recording an album, that's what it's all about, is the sound world. What do you think? What's your answer to that question?

Well, I think that as I transitioned into spending most of my time each day working on making records, I transitioned into listening to records in a different way, too. Now it's almost impossible for me to listen through production, in other words to not hear how a record was recorded, or the methods used in order to capture the performances. When I put a record on the first time it's probably an 80/20 production-to-songs ratio. Sometimes I'd like for that to be reversed, honestly, because I feel like it's a barrier to getting in touch with the music the way "normal" people do, meaning people who don't make records themselves.

Can I ask you another question? Back to the question about BiRd-BrAiNs versus w h o k i l l if you were trepidatious, in your head, what were you going to do? I know we employed certain things, like singing through a [small handheld] tape recorder or the telephone [mic], but knowing where I was coming from, did you do things differently than you would with other bands?

Well, I like to think that I approach each record without too much baggage of what I normally do. I try to tailor my methods to whatever the artist and the songs really need, so in that sense it was what I would consider my normal approach, which is to figure out what the person wants. In this specific case, I felt really comfortable coming up with ideas to get you the sounds that you wanted. I felt like you weren't just gonna shoot everything down. There was this really comfortable rapport immediately; there was a lot of trust, and I felt like if I said, "Let's try this," your first instinct was always like, "Sure!" And hopefully reciprocally.

Yeah!

Because of that, it allowed us to do some things that normally I might not suggest, because the artist won't want to take the time for it. I'm lucky because I work for a lot of people who are very open-minded, but I feel like on this record there was a spirit of adventure that I was really excited about from moment one.

I'm glad, because I felt so uptight in a way. But that's how I feel about making an album anyway, that was what was so awesome about having it be mostly you and me and Nate, that Nate was like, "There's a marimba part there," and there's no, "No, I don't know, what are you gonna play? What does it sound like? Don't you think you should practice?" Instead it was just really quick, it was, "Yes, yes, yes, yes." Maybe because we all have a lot of experience in improvising, in different fields, maybe, but we were all so trained in just going with it, and pushing through the unknown to whatever's going to be there.