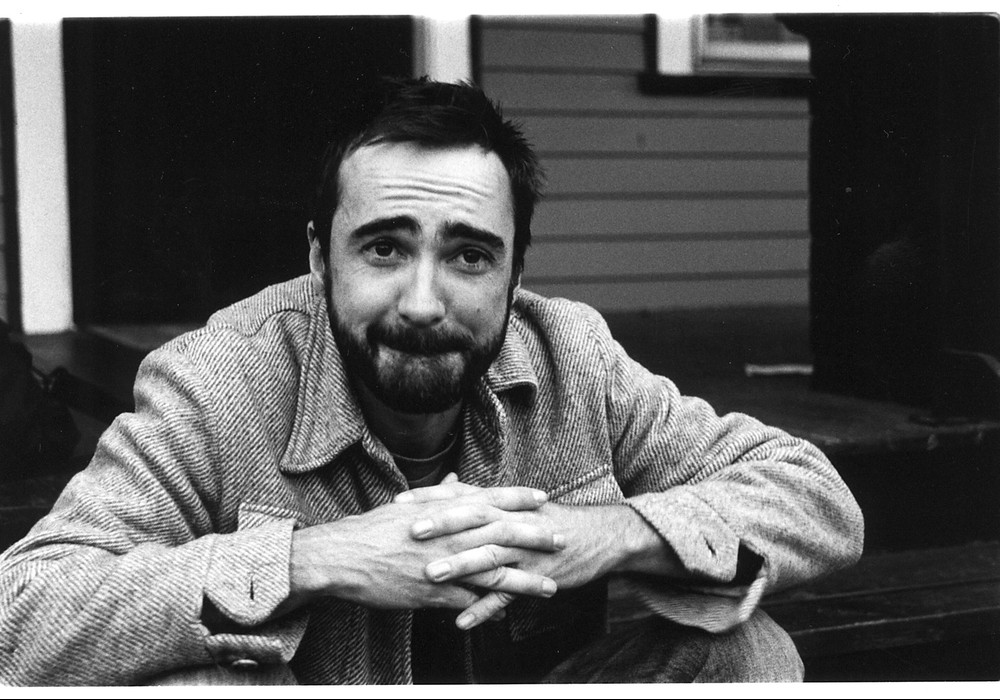

I suppose music technology is just like any other niche in that as you disappear deeper down the rabbit hole, it gets harder to find the other rabbits. Tom Jenkinson would probably qualify as an actual mole by this point were you to fully consider his 15-year reign as the premier virtuoso figure in glitchy drum and bass. But his albums as Squarepusher have also reached into other territory — most famously Music is Rotted One Note, on which he played every instrument himself; a one-man band without any sequencers hosting a jazz-fusion cafeteria food fight. Starting with 2008's Numbers Lucent EP and its follow up, Just A Souvenir, he moved into a friendlier version of digital music. But 2009's Solo Electric Bass is exactly what it implies — and the guy's got some serious chops.

All this constant reconfiguration points to a generally restless and adventurous nature, but what's especially impressive is just how deep his reach extends when it's finally time to change course. He writes his own software for MIDI and audio processing for most of his digitally-minded projects using the deepest nether regions of audio creation platforms, like Native Instruments' Reaktor Core Technology. It's quite astonishing to think that Jenkinson can create music in this fashion at all, let alone come up with something that's truly beautiful.

You've been making extremely technical music since 1996. What spurred you on to record on your own versus a commercial studio?

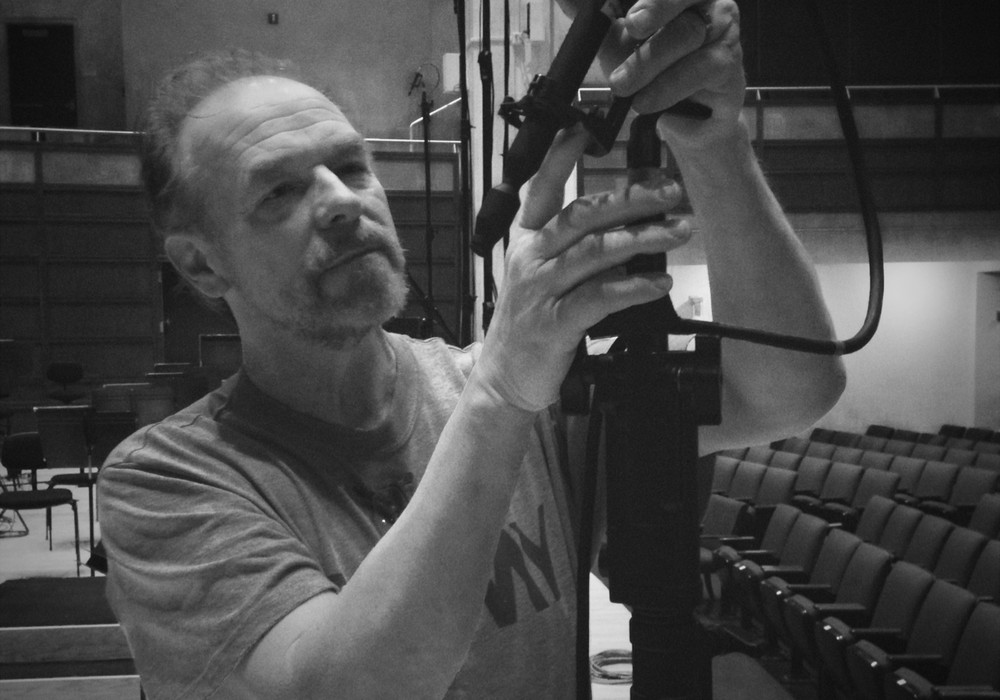

One of the things that really compelled me to want to work with technology on my own was that when I'd gone to studios, I'd found that they were quite stale environments. It didn't seem like an place for experimental work. If I don't feel like I'm making a reach into new territory of some kind, whether it's musical territory or exploring new technological applications, then I think I'm wasting my time. I still don't have a massive amount of contact with that world — I've always operated in an isolated environment. That started off because that was the only way I could do it. When I was kid I didn't have the budget to go to big studios-I had to basically use my initiative with the limited things I could get my hands on. But it set a pattern. I want to set things how I want to set them, and that means some pretty unorthodox ways of connecting all the gear together. It's one of the advantages of being a self-contained operation. If I need a piano part on a track, I'll just practice until it's done. I don't play the piano, but I will if it requires it. I'll attain the knowledge rather than wait. In the early days, as I said, I didn't have the money to pay; and these days I haven't got the patience to wait and explain the ideas to people.

My understanding of your approach has always been that knowledge is a prerequisite to creation. On one hand the learning curve might be prompted by something specific, but on the other hand it's like, "Let's get this out of the way," in order for the creative possibilities emerge. Those two seem like they're in conflict.

It is awkward. In some situations you're making it up as you go along, so in that sense you're attaining knowledge but you're using guesswork. You're speculating on imagining a particular point and you're speculating on the routes to how to get there. It almost sounds like a cliché, but for me it's about always trying to play spontaneity off of a rational, logical, rigorous approach. Without any logical analytical approach, you're high and dry. It's different if you've got the musicians, engineers, producers and so on. They can occupy different mental spaces. I'm doing everything, so I have to encompass all of it in one person. The most stressful times to me are when I'm trying to get takes down: I'm trying to get the sounds right while playing, and the two mentalities are slightly different. I think to play really well you have to let go to an extent — you can't just sit there thinking about the procedures when you're trying to deliver a musical performance. It's multitasking; switching from one mentality and flipping back.

So what are your tactics for juggling them?

I've always had an interest in how the technical aspect of recording music affects the affective or emotional experience of listening to it. I could save myself a lot of effort by getting an engineer in, but my worry is that I'd be explaining ideas to people. I'd have to convey a musical idea verbally to somebody — translating from one language to another. In my head the links are direct. If I'm relying on a verbal form of communication, "I need this kind of sound," then I'm stuck in this dreadful territory, like music journalists or critics when they try to convey a sound using words. I try to avoid doing that at all costs, because I'm not sure exactly what connotations these words might have. In my head I've got very specific connotations. I have a very specific texture that correlates to the experience of green. There's no point in saying, "I need this to sound green" to an audio engineer. I remember reading about Captain Beefheart, and that's one of the ways that he would communicate with his musicians — using evocative phrases to get specific kinds of performance out of them. Personally I don't have any...