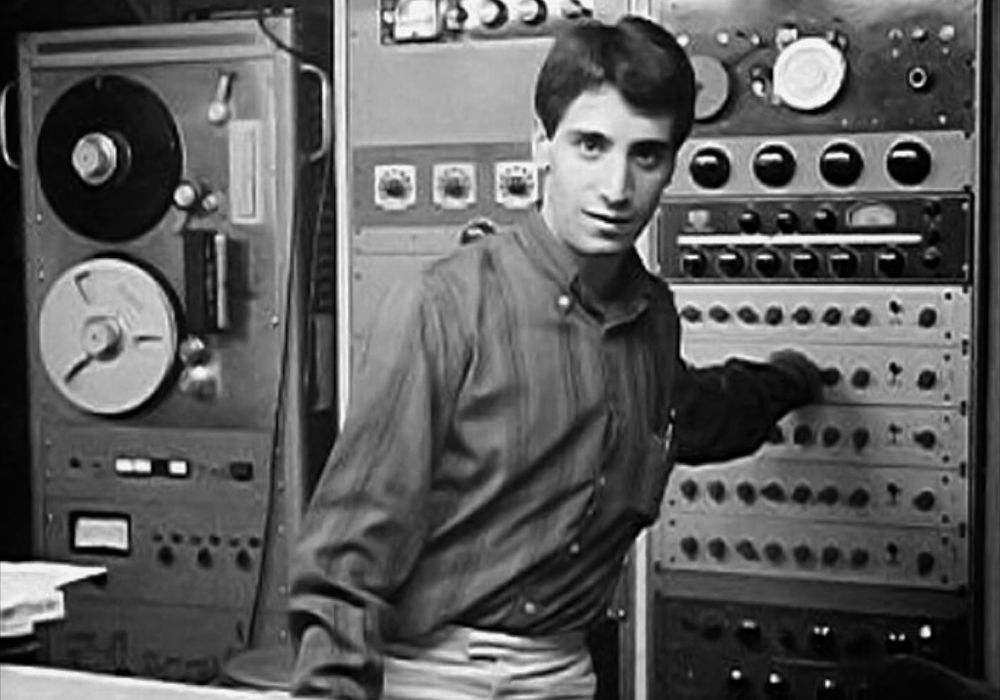

In a recent visit to Memphis, Tennessee, I made time to chat with legendary songwriter David Porter. David was one of the early employees of Stax Records, venturing from his job at the grocery store across the street to work as a songwriter, producer, and artist. His co-writing with Isaac Hayes generated some of the biggest hits, including Sam & Dave's "Soul Man" and "Hold On, I'm Comin'," as well as Carla Thomas' "B-A-B-Y" and many others. These days David is still musically involved, and with Made in Memphis Entertainment there is a plan to bring the Memphis music scene some excellent exposure and support. I dropped by their complex where I found studio designer and architect Michael Cronin getting his hands dirty while putting together some impressive recording spaces. David and I sat down in one of the completed studio spaces to talk about the past, and the future.

Growing up on the West Coast, I always thought rock ‘n' roll and soul music were from different places, and different times. Then I came to Memphis...

That's exactly right. A lot of the music you hear is influenced by R&B. The motivation for me was always, "How good is the material?" I was always trying to find out what "good" meant. When I was a young kid, I loved, "I'm so young and you're so old/This, my darling, I've been told" – "Diana" by Paul Anka. If it was good, it was good. I didn't care. I was passionate about learning all of it, but I also found a lot of inspiration. Having met Elvis and finding out his biggest inspiration was a guy named Roy Hamilton? It just amazes me.

And Arthur Alexander.

Yeah, exactly.

Do you still sometimes feel like the kid that worked at the grocery store across the street from Stax?

I've had a chance to have a little bit of experience. After 75 years, I vividly remember being the young kid at the grocery store across the street and coming over to that building. A country-western label had just moved in right across the street, and that was the beginning.

They had the record store in the front?

They had a record store in the front that was an old movie theater. The Capitol Theater. The neighborhood was changing over. Whites were moving out and blacks were moving in. It wasn't all the way at that point, but the transition was going on. Jim Stewart and Estelle [Axton] got this building. I knew they were making music over there, but I didn't know what kind or anything like that. I was working at the grocery store across the street, so I just went across [and introduced myself]. I said, "I like to do music. Would you be, uh, could I…" Estelle said, "No, we do country." I said, "Well, will you listen to some of my music?" She said again, "No. We do country." That was my introduction. Because there was a record store in front of the building, and Estelle Axton was such a beautiful, spirited lady, I was able to start conversations with her and that ran into getting inside.

Did you ask them about buying soul records that you wanted to hear at the record store? Did you get to listen to things that were currently out at that point?

No, I can't take claim to being that smart. With that record store being what it was, they were putting hit records in the store. WDIA [radio] had just launched, in a powerful way. Those records had an appeal to the community that was making that transition. Estelle was buying what was working on radio; I was just a kid coming over and listening to what they were playing inside the store to sell. She just saw my interest and excitement for music and befriended me. I befriended her as well.

You'd been playing music before, as well as in school?

Yes, I had been. As a matter of fact, I had a record out right after my senior year in high school called "Farewell". This was before I got into Stax. I did terrible with the record but, needless to say, I was already making music. I was singing around clubs. I thought that I wanted to be a recording star. I was not thinking in terms of [being] a songwriter.

Did Stax finally relent? Or did someone say, "Let's do something with you"?

What happened was I was given permission to come inside. I was going into the record store, and Estelle actually got comfortable with me. I finally was able to ease my way into the recording studio. In the building at the time was a fellow by the name of Chips Moman. They didn't call it A&R at that time, but he was the guy who worked for the label. They had two artists: Nick Charles and Charles Heinz. I heard them do the country music, and I just started pestering. "Jim, would you give me a chance to record?" I was pushing him to give me a chance. That was actually the opening of an opportunity there. On the demo session I was doing, I brought in Booker T. Jones, who played baritone horn, Andrew Love, who played tenor sax, and William Bell, who sang background. I changed the words to a song called "The Old Gray Mare," and that was what was recorded. That was the entree to getting into it. Then, right after that, Stax was working with Carla and Rufus [Thomas].

Wasn't Rufus doing radio?

He was a disc jockey on WDIA; a signature voice of WDIA. DJ Nat D. Williams was a history teacher at Booker T. Washington High School, a high school that Maurice White, William Bell, [drummer] Al Jackson Jr., and I went to. All the radio personnel had signature voices. Rufus was a noted and respected disc jockey because of that.

I assume that connection between what was on the radio, what people were wanting to hear, and what was going to be recorded was kind of the catalyst for you.

Exactly. It was. Rufus had that straightforwardness. He was not apprehensive at all about seeking out an opportunity. I wasn't privy to any of the conversation that facilitated it being recorded, but I can only imagine, knowing Rufus. He was like, "You've got to hear me. You've got to hear my daughter." I think Carla Thomas was the voice that probably had a greater appeal to Jim, at that time. So they recorded "Cause I Love You" as a duo, and the rest became history.

Did you start to realize that you could be more of a facilitator and writer?

My ultimate end [goal] was to get in, but I froze during the session. I was singing flat. I had Booker T. Jones, Andrew Love, and William Bell. I thought I had enough ammunition to cover for me, but it wasn't enough. I didn't feel like that would get me in. I started asking for other opportunities to write songs. "I can write." It was not an anxiousness to get an opportunity to write, but I kept pestering for that position. Ultimately Estelle, once again, convinced Jim to give me a chance. I got other people to audition for them to take a listen to as well because I was trying to protect myself, as far as my position there, and I wanted to prove that I had value. I didn't realize it at the time, but I was doing A&R work.

Right. So you were bringing in other artists and saying, "I'll write or co-write," or whatever?

I was given the opportunity of a trial period. They didn't have very much money, but they said they were going to give me a trial period, and I had six months to write them some hits. In those six months I was introducing them to some other talents. I brought Homer Banks there, a classmate of mine from high school. Also Maurice White, who founded Earth, Wind & Fire, but Maurice left and went to Chicago. I started bringing other people and saying, "These people are good." I was writing at the same time. Chips Moman left, Steve Cropper came in. The first person that I officially wrote with was Marvell Thomas. We did a record with Barbara Stephens called "The Life I Live." That's one of the very first records released on Stax [previously Satellite Records]. I knew that writing was my path, so I started working hard to develop that.

It's interesting that it does become a bit of A&R, because you're thinking about who would be good to work with or write for.

It wasn't a big artist roster, at that time. They were considering acts to sign, and I was trying to write good songs, because I was it as far as writing staff was concerned. I was trying to help bring other energy inside the space. It ended up being of value, in that respect. I would think in terms of, "Okay, this person can do this song," or, "This person can do that song," for the few artists that we did have. But I was also looking for other people who could contribute in a creative way. Marvell lasted a short period with me. I ended up writing some initial material with Steve Cropper. I was still looking for a partnership that could ultimately have me competitive to the Holland–Dozier–Holland level. I had high ambitions, right?

There were great songwriting teams back then.

Burt Bacharach and Hal David as well as Holland–Dozier–Holland were the two that I had ambitions to emulate. There was such beauty out of the Bacharach and David writing and composition, and there was such energy out of the Holland–Dozier–Holland team. I was trying to find a way to find a niche for myself. So I was looking for the right partnership.

Yeah, I think his name was Isaac!

His name was Isaac Hayes. Isaac and I knew each other from high school. He went to a rival high school, Manassas High School, and I went to Booker T. Washington. We would sing on Wednesday nights at the Palace Theater on Beale Street. At that time there were talent shows, and we'd compete for $3 for first prize. He had a group called the Teen Tones, and I had a group called The Marquettes. He was a bass singer at the time. All the doo-wop groups featured bass singers, and Isaac had a beautiful tone. I was the lead vocal singer with The Marquettes. I was a huge fan of an artist by the name of Clyde McPhatter.

Yeah, as you should be.

So we knew of each other. I didn't know the level of his talent, but I knew that he was good at singing. We were both gigging around Memphis, so we ended up talking to each other. I talked about what my aspirations were. I wanted to have a successful songwriting team and I needed a partner. Would he consider that? I brought him in while I was on staff at Stax. Jim didn't hire him, or anything like that, but I brought him in for a hot minute there. That was his entrance into Stax.

Were you writing for a certain artist at that point, or was it just to come up with songs and see where they landed?

No, there was a small roster at that time. Ruby Johnson was the first artist we wrote for; a song called "I'll Run Your Hurt Away." But even before that, he and I did a record on Homer Banks called "Little Lady of Stone." We financed the record. We gave 25 percent of ownership of the record to Chips Moman. He had started a new deal over at a place called American Sound Studio, so we recorded it over there. There was a disc jockey working at WLOK. Not the right thing, but we gave him a part of it; we didn't know the record business at that time. Isaac and I created that record, after which I was inside the Stax fold. We wrote some for Ruby, and we were able to develop a bit of respect in short order after that. It wasn't easy, but the door was cracked for us.

When Steve Cropper came in to replace Chips, did you find that a little more conducive with you as well, to collaborate with Steve, as he's more of a musician/bandleader/producer?

Yes. Steve was much, much easier to grow and to work with. When Steve came, he was very anxious to learn and to grow. He was playing a different kind of music, but he had a rhythmic sense that was tremendously special. It just so happened that he found the right kind of linkage with Al Jackson Jr., the drummer who was playing the sessions there. Al Jackson Jr., if truth be known, was really the foundation of the pocket of what became Stax. Out of that pocket that Al Jackson Jr. was able to do, Steve was able to find rhythmic essences that gave identity to him, and also to all those records that were coming out of there. The combination of those two was tremendous. Steve was a person who grew tremendously fast. He was easy for me to work with. The first Sam & Dave song was a record that was produced by Steve and I was called "A Place Nobody Can Find." I wrote that by myself, that was before Isaac and I did anything on Sam & Dave. The B-side of that was "Good Night Baby." That's before Isaac and I started working on Sam & Dave.

When they were tracking songs that you had written, were you in there as part of the process?

I was very much a part of the process. I was doing production at a time when I didn't understand what that was. Isaac and I were producing records, really, without a total clarity of what that was. We were also giving away credits, because we were trying to have the time to grow. "Soul Finger" from The Bar-Kays was a song that was really created by Isaac Hayes and David Porter, in the respect that Isaac came up with the title "Soul Finger." I heard the track, went and got 25 or 30 kids off the street, directed them like a choir, and brought a couple cases of Cokes in there. When I waved my hand up and down, I asked them to scream, "Soul Finger," and they'd just scream. We put that in as the energy on that record. It was the kind of thing where we were doing production at the company for other folks, and didn't really realize that's what we were doing.

Did you get into official production later on as Stax went along?

No. That was a part of the process from the get-go. It was an experience where everyone was learning, everyone was growing, and everyone was doing whatever their skill level enabled them to do. We were in there working on different records, different songs, and with different artists. We were just simply trying to make something work. I started producing records with Barbara Stephens on "The Life I Live." That goes all the way back. I just didn't realize that's what it was. If you notice on some of the earlier records at Stax, you'll see "Produced by Staff." Well, in actuality it really wasn't produced by the staff. There were individuals who were, in fact, producing records. But there was a communal spirit and energy there. It was a family. No one was hung up on getting credit or anything. But those pennies could have happened.

You were working with great musicians whose instincts are spot-on. They're going to play well and say, "What about if we do this?"

That was the magic of what happened at Stax Records. We were trying to compete with some mammoths, like Motown and Atlantic Records. No one had so much cockiness or confidence that they felt it was all them. We knew we just had to make it happen. There was a communal spirit. We'd all pitch in and try to help make each of these records as good as possible. That's where the family essence came out in the Stax environment. Then Jim wanted to develop it into a system in which people could get paid for it. So that was why we started giving proper credits and that kind of thing.

People want to be compensated, or credited at the least.

Yes. Folks didn't understand how that part of the business works. It was a communal thing. Jim would take care of folks. You still needed to have the business part of it taken care of properly, so there was a willingness on his part to make sure of that.

You're starting a new family here, basically? With Made in Memphis Entertainment.

Yes. The whole experience at Stax was a tremendous thing for me. It gave me a level of success that I never, ever imagined. It also taught me the beauty and the power of a community working together to make something meaningful happen. Having learned some of those principles, I used it with a non-profit that I started [Consortium MMT (Memphis Music Town)]. I also am using that with this record company [Made in Memphis], and what we're doing here. This is bigger than just building a studio. This is building a credible, energized industry again for the creative-minded appreciation for music. There's a process to getting there. This space and this building is going to be geared toward coming up with informational ways to pass it on to young folk. The fact that I've been a part of what happened before – and saw that, even though it's a lot of work, it can happen – I know, with total confidence, that it can happen again. That's what this whole operation is. It's a goal of putting together artist development; a creative foundation in such a way that people grow together, but also create a signature identity for an area that already has a brand that's respected all over the world. I think that happens, first with creating an environment where people can work and grow together. That's why we have three recording rooms inside of this facility. We have three additional recording rooms that writers can write material in. If they so choose to, because of technology today, they can actually make records in each of those writing rooms. But I think the motivation for that comes out of what Stax taught me, as well as the credibility that Memphis earned. It also comes along with what happened at Hi Records over there with Willie Mitchell, and with what happened at American Studios with what Chips Moman was doing. Just to know that you could pull all this great energy together, that's what this is all about. We have some great, great talent in our city.

How do you gather the right people and build the right teams?

The great thing about this is because of the respect that Memphis has as a place of music that has happened in the past, and because, knock on wood, I'm still here, I think that I have a potential audience of people; young folk, who will listen to me, and come as a gathering spot to a place where they can show their wares. When that happens, we show them how proficient we are at doing a level of quality they'll be happy with. That enables them to have energy to let their own creativeness come out. I think the artist development part of that concept lives inside of that world. If you're good enough to get into the place initially, you can grow. That was the thing at Stax. If you were good enough to get in, you'd have the opportunity to grow. We saw what happened. I believe the same thing can happen here. We have the facilities here.

How do you vet the people who are coming in?

Part of that lives in this concept. In the Consortium MMT, we shop those talents throughout the industry. We send out notices to all the major companies, that they need to come to Memphis and tap into some of this talent. We just had a showcase – sponsored by Universal Music and Concord Music Group – where A&R and publishing folks came and listened to a talent pool of several different writers, producers, and artists to consider for signings. Because I'm a founder of that organization, Made in Memphis can't touch that talent – at least for a year or two. That would be a conflict. But some of the people who don't make it to the Consortium program, but want to be in the music industry, can simply come and seek an audition for this company. Some of them have done that. This community is evolving into a recording mecca again.

We hear a lot about how there isn't a studio system these days, and you don't bump into so-and-so in the hall and collaborate. Or the way Stax was working, where you'd have a variety of people in and out, doing different things. Do you feel like this will help create that?

I think, without a doubt, that this will play a role in changing that mindset. People live off the credibility of music. It has an emotional connectivity to people that's inescapable. If that's the case, if you find that people have to have music like they have to have food, why not work on elevating the quality of it into something that people want to hear? Why should you run away from emotional connectivity through music? To develop places that really get serious about making music resonate with people is a good ambition to have. It's already been proven that it's successful, based on the catalog value of so many great artists. I think that artist development, and that role, is a role that I'm willing to work hard and passionately on to prove the validity and credibility of it.

Do you feel like Memphis hasn't been well-represented in the music business?

I think it would be true to say that there has been a lag. But it doesn't mean that it's a lag because the talent doesn't exist here. The talents that have existed here, though many of them have chosen to leave and go to other places. Justin Timberlake was here. Three 6 Mafia was here. Stevie Wonder's touring band; these are Memphis kids. The Bruno Mars band members are Memphis kids. The list is long. The talent has always been here. Now we're working to show that talent can stay here; let's make the message of credibility resonate as a base out of Memphis. Let's have a vehicle where you can rest assured that we'll get that message out. That's what this is. We're doing all the due diligence. We've not even promoted that we're here yet, and we're almost finished with two albums. We've almost finished with the total construction of the three main recording studio rooms. We want to be able to say, "Not only are we here, but this is us." We'll be off and running in a very powerful way in 2017, with marketing, promotion, and the whole nine yards. That's the reason why we've kept it quiet, up until this point. We want to do our grunt work on the front end, so that we don't have to talk about what we're going to do, but rather can talk about what we're doing. I think that the community itself will be extremely proud. We certainly saw that just a few nights ago when these major record companies came, and they were blown away. The talent was exceptional. I think that there's tremendous hope and excitement for what can be coming out of Memphis. It's an exciting time for Memphis. I want to build a credible, creative community in this city again before I'm out of here.