So you say you know Kurt Bloch, guitarist/songwriter for the seminal '90s mega-pop band the Fastbacks. And maybe you know his involvement as the "junior" member of the Young Fresh Fellows. But did you know that Bloch is also a producer? I would frickin' hope so! The man has produced Mudhoney, Nashville Pussy, Flop, Sicko, Pure Joy and many others. Bloch is one of many Seattle-based producers that make being in a Seattle rock band so awesome. Phil Ek, Jack Endino, Conrad Uno... Bloch is in the same league. Not only is he a musical genius and master of the "live sound" recording, the man is fucking funny! To this day, he is the only producer I have worked with who gave me instructions with a French accent. This interview was done after Bloch released a collection B-sides and rarities from the Fastbacks called Truth, Corrosion and Sour Biscuits and the album from his new band, Sgt. Major, titled, Rich Creamery Butter. Both are released on his new label, Book Records.

You started your recording career by recording Flop's first album, Flop and the Fall of the Mopsqueezer! In a review you were quoted as saying, "The theory was that we should try all the things normally discouraged in other studio environments." What did you do that was "normally discouraged?"

It's wrong to think that that was the first thing I ever recorded. It was the first thing other than my own band that I ever recorded. I worked on the Fastbacks' albums — the first one Conrad Uno [Egg Studio] recorded and on the second I collaborated with Conrad. On that one, he [Uno] kind of let me do whatever I wanted. And on the third one, Zucker, Conrad told me, "Just go and do whatever you want," though he might have been there for some of the basic tracks. That record turned out pretty good, and after it came out is when Flop came to me and said, "Oh yeah, we want to record a record!" They didn't have a label, didn't have any money, and I said, "Wow! This is perfect. I know these guys, they're my friends and they don't have any money. If they pay for the studio time I could just do it and learn." It pretty much was an exercise in disaster to some extent, but it's still a great record.

I was just wondering if you were doing things like putting drum mics in different rooms or something.

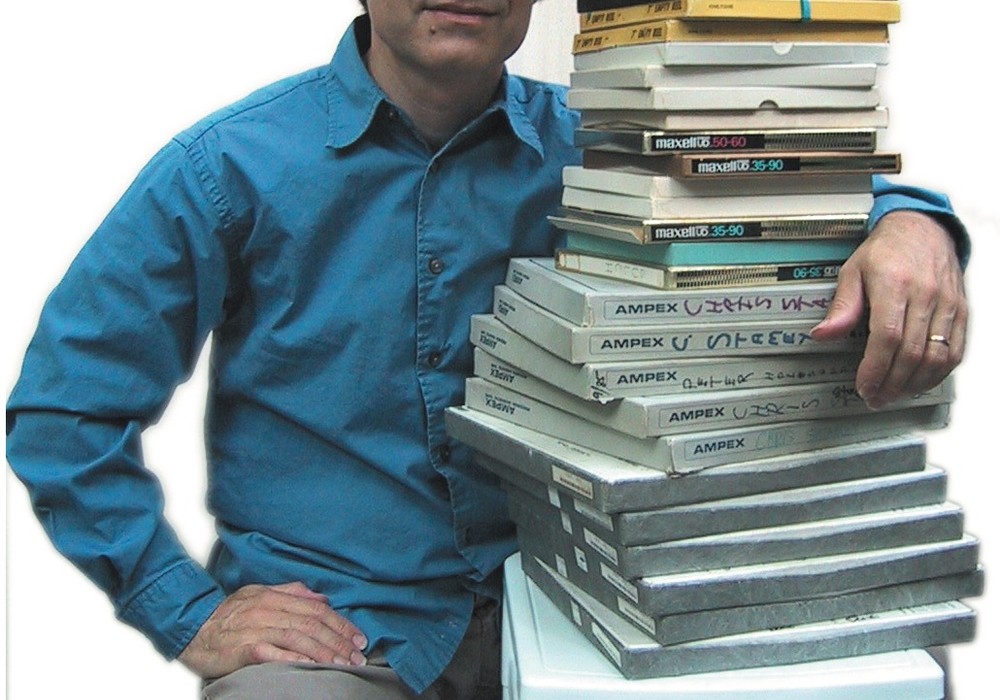

No. At that point it was pretty conservative. As far as drum mics go, there were a couple of 414s for the overheads, 421s for the toms, and 57s for the snare's top and bottom. There was probably an RE20 on the kick drum. Just fairly normal things like that. The one thing that you start doing that is nasty is cranking EQ every chance you get. On the track, going to tape, coming back from tape, just EQ, EQ, EQ everything. Another thing I learned not to do early on was compress drums going to tape. I don't know what the theory was in my feeble brain was back then. Now that I think about it, maybe it was working in a studio that doesn't have much gear. There were maybe a couple of Symetrix compressors at Egg, a DBX 166. You know, there are only four channels of compression. It's not an option not to have everything totally compressed. Might as well compress everything going to tape, and then you don't need to compress it again. [laughs] It became impossible to work with later, but I didn't know. It was mixed very quickly, just a few days, and we took it to another studio for sequencing and editing on Pro Tools in '91 or '92. It gets bounced and sent off to John Golden — "You know I think there's something wrong with this. I'm just having a hard time getting a good sound out of this. I've been having to add a lot of top end. I can't tell you exactly how much, but the number '10' and the letters 'dB' keep cropping up." I tell him, "I just don't know. It was fine when we left it." "Well, you know you don't really have to put that much compression on your mix." "Oh yeah, you do." "No, you really don't. If you really want it super-compressed, you just tell me and I'll do it down here." After he dinked around with the recording for a little bit, he called me back, told me the mixes were screwed up, that they were out of phase, and that I needed to do something with it. We found it was out of alignment by a few samples. So we clicked back in and obviously the mixes were still totally compressed and scuzzy sounding. When the record finally came out, everybody was so nice to me. "Wow! You recorded that on an 8-track? It sounds just fantastic!" "It does? God, maybe I'm a recording genius." It's still a great record, but it was such a stepping stone for me on learning what to do and what not to do for recording stuff. Its high energy is good, but it's a terrible recording.

You can just say it's "lo-fi" and it was the sound you were going for.

"Oh yeah, man, that was lo-fi, and it was great!" It wasn't supposed to be. But I listen to it now and I still think it's killer.

I've read interviews where you've touted the fact that you haven't had any schooling in recording.

To be proud of not going to school... I don't know if that's a good thing or not. But having knowledge, especially in the recording field, is not a bad thing. [laughs] Knowing how mics work and knowing a little about things like that. Theoretical knowledge can only do you so much good in the kind of recordings I end up doing. They're usually "get in and do things as quickly as possible and hopefully it will sound good." More important than the theoretical knowledge is a working knowledge of how things behave, of what works and what doesn't. Of which you're probably not going to get at a recording school, but then I don't know — I've never been. I certainly don't think school is bad at all, but for the amount of money it costs... I don't know. It's really hard to say.

You seem to emphasize the importance of capturing the sound of a band live...

I like recording ROCK bands. So many people don't go to clubs. They don't see bands. I'm not saying that's bad either, but if you want to record rock bands and you want to know what they're going for as far as sonic assault — it's good to see what the people who like the band are seeing. Certainly it's not always a high fidelity experience. Sometimes they sound better live than they do on record, and every now and then there are bands that sound better on record than they do live. But the people that are going to buy the record are the people that usually like going to shows. If you don't know what that experience is like you might not have quite the picture of what things should be.

In previous interviews you've talked about the importance of the room you're recording in.

Where you go to record is very important, yet sometimes you don't always have much of a choice. Like that first Nashville Pussy record [Let Them Eat Pussy] there was no question — they wanted to record at Egg. Fine. You know how big that place is — it's living room-size. To put a band in there, it's genius for the overall effect because you can put everyone in there and not wear headphones and just blast through the songs. It's great. But as far as an actual room for getting sounds that way, it's certainly not the best. There's no way you could record two Marshalls, a SVT, and a drum kit in a room that size and get what most people would consider a proper sound. But how many records do we like that were recorded under those conditions? The bands are paying for it themselves. You can't always go to a $750-a-day room and track. I found at Egg you do get a lot done in a short period of time because you can record and everyone can hear. And you can keep your basic tracks because, there again, if everyone starts wearing headphones and gets isolated, it's great for sound but then everybody starts hating their basic tracks and needing to go back and record stuff. Which is fine for me too, but what you get on your live take with everybody playing in the same room and no headphones, just everybody blasting in the room with whatever isolation you can possibly get (which is not much), your quality of band tracks is going to be so much higher. To get that same intensity, that same quality of playing, with re-cutting all the different tracks... it just takes so much to get wired back up to that point. You can put down a rhythm guitar track and somebody can play just killer while they're playing in the same room as the drummer and the bass player. Then you put them in the studio, listening to the monitor speakers, and you might have to run that same song five or six times for them to be able to pick up on the excitement they were laying down earlier; even just playing a rhythm guitar or bass or something like that. Most bands I record are used to playing live shows. That's where they deliver the goods. Sometimes, not all the time, they're not the most accomplished, seasoned musicians individually, and so you try to get them to do overdubs and it's not something they're used to doing. But to play in a room with everybody there, they can just kick it out.

You're an artist yourself, but then it sounds like you really don't try to put your own artistic ideas into others' recordings. Is it because you don't feel it's your place?

With most of the rock bands I record with, they pretty much know what they want to do. They want the record to sound like a real band playing. What is a record producer? Anybody who does that job could come up with a totally different definition of what it is. I think of it as being the guy that you call to get the job done the way you like it. I don't get calls from record labels saying, "We're gonna hook you up with this band because we think you're going to do it justice and make a record that will be viable and sell." That never happens. I'm probably the last one they would call for that. All the calls I get are from bands, from somebody in the band that is like, "We really liked this record that you did and would you do our record?" I'm just guessing, but I think the reason I get those calls is because they don't want somebody to tell them, "Oh, you know you should make a funkier bass line for this song." Not to say I'm not interested in going through pre-production and listening to bands at their practice space and giving them ideas, but it's more of how to make stuff work better, like "Bass player — listen to drummer. Pay attention. You guys have to get together on this." "Singer, you sound like you're not sure of yourself here." You're just pointing out things to consider. You know, I totally love the idea of adding a bunch of shit to people's records. It's so fun to do and I can just sit there and make overdubs and come up with new melody lines and extra backing vocals and different instruments. I love doing that sort of stuff but it just doesn't usually fit in with the kind of music that I generally do.

So someone would have to ask you for it?

Right. Oftentimes people will go, "We really want you to get involved with editing and working on vocals. We really want your input." And oftentimes they don't, really. It's sort of funny but it happens often enough. A lot of the times the bands are just trying to get people to distill things and get it down to the minimum amount of stuff you can put on a record and still have all the ideas in there. There are those people that are like, "There's a lot of stuff we have to overdub because we can't quite do it live." I bet you can do it. Learn those extra melodies and play them. So it's a little harder, big deal. You'll like it so much better when it's done and you'll know how to play it so when you play shows, the music will all be there.

Do you leave a lot of the sound to the band, especially for recording? Like when they have cheap-ass equipment and their guitars sound like crap.

It depends on the band and how much time there is to make the recording. Originally, I was probably like, "You can't record on that amp, it has to be a real Marshall," and, "Why would you record on that amp when I could bring in this one." But sometimes it turns out that crappy amp and guitars that are kind of fucked up just sound great. A lot of times that's where the coolness and individuality of the group is. Sometimes there are strange choices of equipment.

But it's what they're limited to.

Sometimes I'll bring in a few extra guitars and the bands will be like, "Wow, this is great! We've got to try this." One session, I thought nobody would want to use anything, and they were just all over everything. There are times when I'll bring in a bunch of guitars and a few amps and the people will look at them and get scared. The most common of problems with instruments are the low notes on the bass. F-Sharp and G are going to be sharp, and you'll listen back and get seasick. Oftentimes people can't tell because they've heard that sound so much that, to them, that's how the song goes — you don't want to tell them that they're blind to out-of-tuneness. You have to say things like, "Maybe we should get this bass fixed up a little bit? Or maybe try another one?" Or, "When you play those low notes, be real careful; don't push too hard."

You don't want to make it seem like an intervention. "I'm sorry Bob, but your bass sounds like ass and we've all been wanting to tell you."

Who's to say people don't know what they're doing? You listen to the first albums of bands and why are they always the best ones? Because they didn't know what they're doing. They didn't let anything get in the way of how they actually were.

Recording your own band: Do you prefer to produce it? And does it help you with songwriting, especially when you know how you want it to sound on a record?

In some ways it gets harder and harder to stick to what I recommend other people doing. I've just spent time making some song demos for my rock band and I try to make them really good just because it's fun to do. But as easy as it would be for me to put eight vocal tracks and five guitar tracks on these tapes, I can't do that. I have to figure out how to make realistic demo tapes with a guitar track, a bass track, drums, a vocal and a backing vocal — and make that as exciting as possible. You have to have a rock band that you like. You have to like how everybody in your band plays. You can steer them in directions but you can't force them to do anything. I can make demos and have the drums sound the way I think they should be and have the bass the way I think it should be, and that's kind of a good way to get someone going in a particular direction. "Alright, here's kind of an arrangement, but do what you want. Play the way you play." Keep an open mind. Celebrate people's strengths and weaknesses. Enjoy playing with them and being around them.

And realize too that suppressing them isn't going to make it fun for them to play. It's going to turn it into a job for them.

Yeah, but I was that guy! "This is how it goes! You're fucking it up!" [laughs] Every once in a while it will happen in a session. [The band will] start fighting: "Fuck! If you're gonna play it that way, then forget it!" Then they'll go outside, but one of them will come up to me and say, "I'm so sorry you had to hear that. We just blew up. This has probably never happened to you before." And I just kind of laugh and remark, "You have not even seen fighting in the studio." Until somebody has quit the band during the recording — you know, the singer has left during the session in tears, and you don't know if the day or the entire session has been ruined. The type of person most likely to ruin any recording session is someone from the record label. Not very often do I record for major labels — and I probably never will again — but it's the guys from the record label that just don't understand how rock bands work. They think they can come in there and put their magic stamp on things. They'll get on the talkback mic while the singer is out there in the vocal booth. Let's face it: Most singers in rock bands do what they do and they don't want it to sound fucked, and they don't want to sound like a jerk, they just want it to be as good as it can be. But then you got these label guys in there, "Uh, yeah, that's great, but why don't you try another one? And this time, do it a little sexier." And they're talking to a guy in a rock band trying to make a kickass record. But then, can you "shh" the guy that's paying for the session? Obviously they don't understand that it's people that are making these records and not some machine.

Lots of producers have gotten to go to the Grammies, but only you have gotten to go with Nashville Pussy. Any stories?

[laughs] The Grammies are awesome. The show is in two parts: The first part is the kind-of warm up part, where they give away a bunch of awards but it's not filmed. It goes on for about an hour, then they take an hour break, and then it's time for the TV show. The TV show is very regimented. There's no drinking. You can eat the hot dogs and nachos they sell in the lobby, but you can't bring them into the auditorium. We were up front for the first part and they put us kind of way in the back for the TV part, which was hilarious. We joked about what we would say if we had to go up there, but we never did. We knew it wasn't going to happen, but we didn't know for sure. But it was great to watch them read, "And the nominees are Na... Nashville Pu..." We could see other people thinking to themselves, "Yeah, that's not going to win." When it's done, all these people have these crazy parties. These parties are in the ballrooms of hotels, where there are five huge rooms with five bands playing and packed with people. Red carpets everywhere, food, a bar, everything. Then you leave for another party that's just as huge. Just phenomenal amounts of partying. And everybody was there, networking, while we were just laughing and having a good time.