As we wind our way through the crazy world of recording music and learn more, sometimes we look back and suddenly realize just how great some records we'd taken for granted actually sound. One day it hit me that all The Doors albums had a high level of clarity and sonic quality, and upon investigation the name Bruce Botnick came to light. Bruce worked as an engineer (and producer on L.A Woman) on every Doors album up until vocalist Jim Morrison's passing, continuing to work with the group on subsequent live albums, box sets, remasters, remixes and documentaries.

But there's much more to Bruce's career than this one group. He was an engineer or producer of many albums for Love, Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass, Brasil '66, Van Dyke Parks, Buffalo Springfield, the Ventures, Tim Buckley and Eddie Money, and as the producer/engineer behind the MC5's legendary Kick Out the Jams. Did I mention he worked on the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds and "Good Vibrations"? In the late '70s Bruce became well known as a scoring mixer of film soundtracks, especially for his work with composer Jerry Goldsmith. He was an early advocate of digital recording, and today keeps abreast of these changes and even performs beta tests for Avid/Digidesign. We dropped in on Bruce at his private studio in Ojai, California to pick his brain and figure out why his recordings have always sounded so damn good.

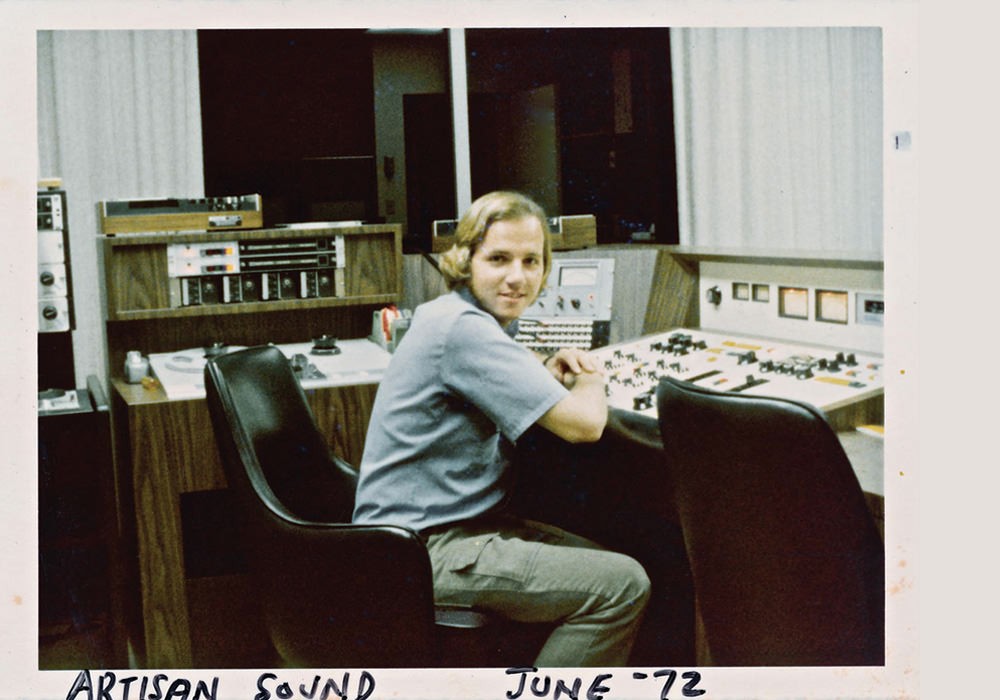

LC: So you started working at Sunset Sound Recorders around 1963.

Something like that.

LC: What were you doing before then?

I had my own record label. I was recording school orchestras and things like that and pressing LPs. I used to go to Radio Recorders and cut mono lacquer masters and press with Research Craft using their new, anti-static vinyl. Then I got a job working as an apprentice engineer for Liberty Records' recording studio [Liberty Custom Recorders], the home of Johnny Burnette, Bobby Vee and the Chipmunks.

LC: I interviewed Snuff Garrett a while back [#73].

I worked with Snuff. Lovely man. He's got great stories. We used to record song-publishing demos for Hill & Range Music, which were [songs written by] Jackie DeShannon and sung by P.J. Proby for Elvis Presley. We were doing these all the time and Snuff was involved as a Liberty Records A&R man. He was the shining star, producing the hits. I started there and then Liberty Records was sold to Transamerica [Corporation] and they closed down the studio.

LC: Liberty Records had their own recording studio.

It was upstairs on La Brea Boulevard and Challenge Records used to be downstairs, so we had the Ventures recording there fairly regularly. When I was without a job I just started walking the streets, walked into Sunset Sound Recorders, met [Salvador] "Tutti" Camarata and talked to him about big bands and the way to record them. He was intrigued and that was it.

LC: You mentioned the Ventures. Were those sessions at Liberty?

I did some of the Ventures at Liberty, but when I left for Sunset Sound Joe Saraceno, who was their producer at Liberty Records, brought them to Sunset Sound. So we'd record the Ventures — do side one from 10 am to 1pm and side two from 2pm to 5pm, edit it together, cut masters that night. The album was on the street in five days.

LC: That's pretty fast.

That's the beauty of mono.

LC: Of course. Do you remember which records those were?

I can't remember the names. They were great guys and they really just came in and played.

LC: That's a quick way to make a record. Before Sunset Sound you'd been working at a studio affiliated with a label. Now where were the jobs coming from?

It was affiliated with a label — Disneyland Records [now Walt Disney Records]. Tutti Camarata was the head of A&R [for Disneyland] and he built the studio [Sunset Sound]. We had Annette [Funicello] and all the Storyteller albums. In the morning I would be recording commercials from 8 am to 10 am and then do a Storyteller album where Mickey, Donald and Goofy would come in. We'd take Disney's animated movies and do them like radio shows. In the afternoon I would do some jazz or some rock 'n' roll — mainly surf music at that time.

JB: Was Mickey Mouse in costume?

[laughter] No, he didn't have to be. He had a tail and four fingers. He was born that way!

LC: So you could be doing a children's record and The Doors in the same day? Same day, absolutely — and a commercial for Midas

Mufflers. It was normal! Let's say that I would do this children's record and we were doing songs. We'd bring in a band, maybe eight to ten pieces with Annette in the vocal booth. We'd record for three hours, tear that session down, put up a jazz session for Pacific Jazz [Records] and then tear that down. Then The Doors would come in or whomever else. This went on and on and it was no big deal.

LC: Do you feel like that kind of variety really reinforced your skills?

I loved the variety. In those days radio didn't narrowcast like they do now, where you now have a hip-hop station, an adult contemporary station, an oldies station, oldies jazz, oldies rock 'n' roll and oldies middle of the road. Back then the local stations all around the country played everything. It was popular music. It didn't matter. It could be Dave Brubeck's "Take Five" into a Frank Sinatra song...