I opened my commercial recording studio (Jackpot! Recording) in 1997, after years of simultaneously having a busy home studio while working day jobs to pay the rent. Making this leap to a full-time recording engineer/studio owner was terrifying. I remember thinking I was making a big mistake; what if nobody booked the place? How would I find time to work on the recently started Tape Op Magazine?

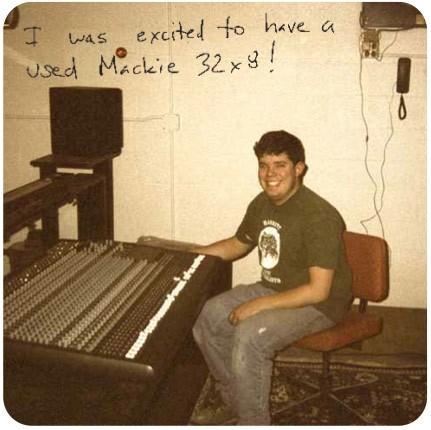

My home studio was run as a part-time, small business. I basically used money from these sessions in my basement to pay for new recording equipment, and, in the meantime, I didn't turn a profit. But I'd been getting busier over the years and it felt like now was the time to move it out of my home and into a commercial space.

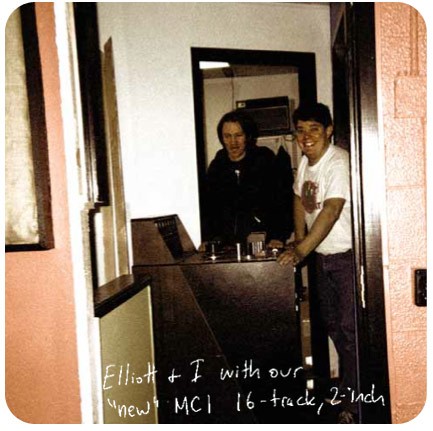

I'd partnered up with songwriter Elliott Smith, once we both realized we had the same studio space plans in motion. Having a partner also gave me some leeway on having to buy as much new gear, as well as freeing me up a bit from covering the entire rent and filling the calendar by myself. We found a space to lease, built a wall and sound treatments, and moved our gear in. I had taken out a small loan from my grandfather and maxed out several credit cards. When we had an opening party, a friend brought over a mutual acquaintance. Our conversation went something like this:

Her: "You are so lucky! You are so lucky! You are so lucky!"

Me: "Uh, okay."

Thinking about it later, I was annoyed. "Luck?" I was putting my life on the line and she calls it luck? As it turns out, luck came and went, but hard work and sacrifice got tangible results. In the early years I worked as long of a day as a client would demand, for a flat $250 fee that included myself and the studio time. During one session I was a little too free with my information and I told a client what my rent and utilities were each month. That conversation was uncomfortable:

Him: "Dude, you must be making bank."

Me: "Uh, it doesn't feel like it."

Of course it didn't. At the time I was paying off $30,000 in startup costs, and fronting the printing bills for Tape Op on the same maxed out credit cards. With 250 paying subscribers and basically no advertising in the mag (this was before John Baccigaluppi partnered up with me), you can gather that I was losing money on this magazine venture.

I also worked my ass off. I would engineer a 12-hour session, eat a burrito, sit in my office for three hours (post-session) editing Tape Op, and then go see bands at EJ's, Satyricon, or La Luna. Hitting the clubs obviously helped get my mug out there, and many musicians knew I was running a new, affordable studio. Yep, networking is also part of the job, albeit often a fun one. At 2 a.m. I'd make my way home and pass out from exhaustion, only to wake up in the morning and repeat this process. Oh yeah, sometimes I'd also have a gig to play, or end up driving several hours to the printers to drop off artwork. Days off? What are those?

I won't make a super direct correlation, but my first two marriages did fall apart during this time. I stopped playing in a band. I'd been warned by Greg Freeman [Tape Op #1] that friends would stop calling me to do stuff on weekends or to attend parties because they would assume I was too busy, and he was correct. It also seemed like every time I had a freelance engineer in and tried to take time off that that would be the moment all the equipment would break down.

Life feels a little less hectic these days. When John came aboard and helped turn Tape Op into a legitimate magazine, he took a load off of me. I had never quite gotten into the flow of layout, printing, and distribution. Nowadays, thanks to him, I get to focus on interviews, editing, and travelling to conferences for the mag. We have a wonderful team of people that help out. I even have dates permanently noted in my calendar in order to set aside time to assemble a new issue. Luckily, all the sacrifice also led to a stable studio situation, and I have even been able to hire employees to help with managing the studio and assisting on sessions. Even with all of this in place there are months with enough empty days that we are barely covering expenses. There are also times where I work ten-hour days for several weeks in a row with no days off. Remember, this is 18 years in for me now.

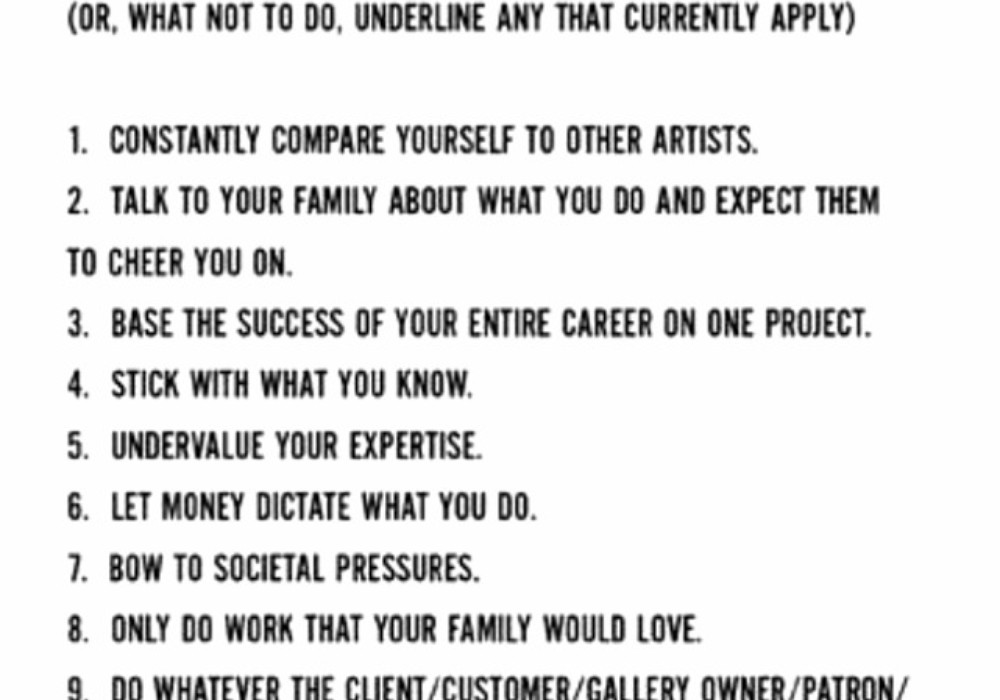

Why am I telling you this story? Because some of you may be in similar situations. Possibly you are on the precipice of "hobby becomes job" like I was. Maybe you are just starting out and need to know how much of your life you need to put into this world to succeed. Or perhaps you've run a small studio for years but it looks like others have it easier (hint: they generally don't). Or maybe you simply wonder why friends stopped inviting you out!

It's not an easy path, but I'm not sure I'd want my life any different than it was and currently is. You need to be fully immersed in this world and ready to make sacrifices if you want to see things happen. I'm glad I did it.