I wasn’t surprised when I heard that Daniel Johnston had died. It was 9-11 and for me, there would always be a connection between Daniel and 9-11. In the days after the attack, when everything Stopped Making Sense, Daniel Johnston made more sense than ever. I first heard Daniel's music in his home town of Austin, Texas. As everyone knows, Austin was the capital of laid back cool in the ‘80s. It was the home of MTV’s “The Cutting Edge," SXSW, the cult movie Slacker and Timbuk3 sang “The Future's So Bright, I Gotta Wear Shades” as Austin’s anthem.

My band, Future Neighbors, had booked a gig there. We were sitting on the floor of Brian Beattie’s bungalow [Tape Op #53] and he popped in a homemade cassette called Hi, How Are You. Brian was becoming one of the first great digital engineers, and played bass in Glass Eye, my favorite band at that moment. His bandmates worked at the first (back then, only) Whole Foods. They were smart. They were cool. They were Austin.

The next time we played in Austin at Liberty Lunch, Daniel was at the show! The shy man that wrote those compelling, disturbed songs! Before Rick Astley had become the first internet joke, and we knew how BAD Michael Jackson really was, Daniel's magical songs were a breath of real air, and it was spreading.

Why was Daniel's music so compelling? How did he become so widely known before you had “follows” on Instagram?

It is likely that his music was both a symptom and a form of therapy for the mental health struggles he had over the years: The high highs of songs like “Rocket Ship” and “Sun Shine Down on Me” or the painful lows on songs like “Wish” or “It’s over,” or they could be just plain funny.

In “Grievance” he sings

“I'm heading out west

Gonna find me the best

Well, I played the game but I failed the test

If I can't be a lover then I'll be a pest”

Sometimes combining them all, In “Living Life “ he sings:

“There's hope for the hopeless

I'm learning to cope

With the emotionless mediocrity

Of day-to-day living”

I don’t think Daniel was unaware that he was somewhat of a commodity. He sings on “Monkey in a Zoo":

“All these people who want me to do tricks for them

Like a monkey in a zoo

Throw me a peanut

Laugh and make jokes

But I've had enough peanuts and I'm ready to croak

Like a monkey in a zoo”

As an “outsider artist” he was a part of a group that included Wesley Willis and Hasil Adkins. It’s no wonder he appealed to mainstream outsider artists like Mark Linkous and Kurt Cobain. The fact that he outlived and outproduced (17 “studio albums”!?) both of them speaks to the therapeutic value of his prolific songwriting.

Every songwriter knows that feeling of chasing after a song… you leave behind your everyday responsibilities and your troubles literally diminish. Daniel knew how to compose. Listen to the bridge of "Monkey in a Zoo” – it’s almost Tin Pan Alley. The fact that his songs have become an “Alternative American Song Book” and covered by so many diverse artists illustrates that. If the primitive recording and his almost painfully plaintive singing on many of his records are too much for you, check out the many cover versions out there.

I am especially fond of Dead Dog's Eyeball: Songs of Daniel Johnston – a collection of his songs by Austin singer K. McCarty (of Glass Eye and produced by Brian Beattie). She was a close friend of his and truly understood his genius.

Returning to Richmond from that show in Austin, with a dubbed copy of Hi, How Are You, it truly seemed the future was bright .

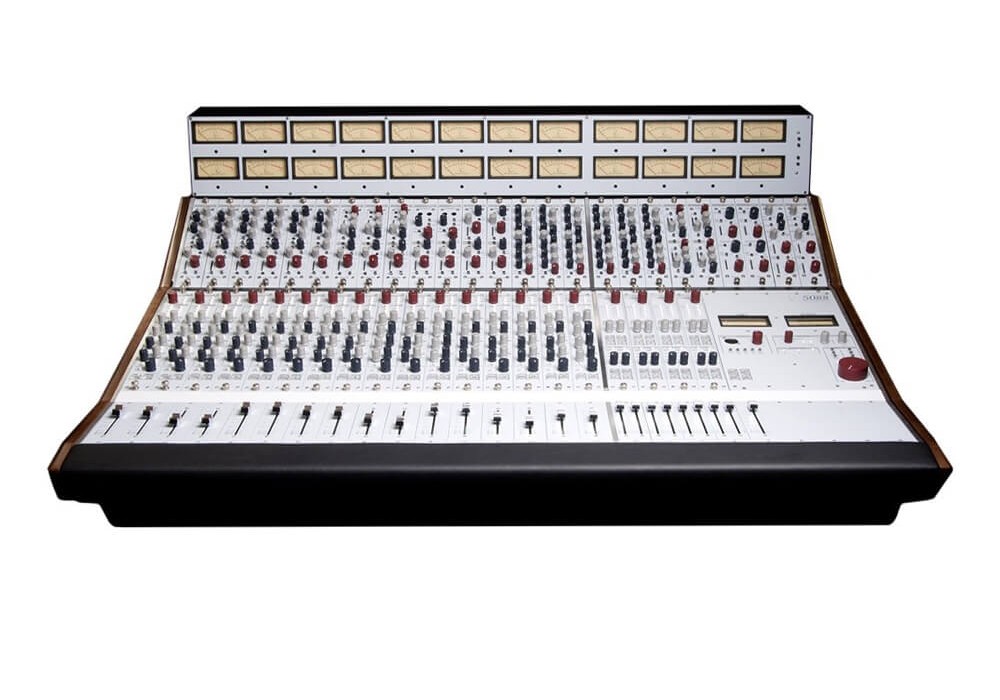

Fast Forward (literally, on a Studer 2-inch 16-track tape machine) to the summer of 2001. For 7 years Sound of Music Studios had been recording artists as diverse as Dexter Romweber, SparkleHorse [Tape Op #12], Royal Trux [#11], Avail, and Hanson. When I got the news Daniel was going to come record, I couldn’t believe it! I told everybody, “Even if the studio closes next month, I can say Daniel Johnston recorded at Sound of Music.” We were stoked! That summer was full of major label records and travel plans to Europe, but you could tell there was something not quite right in the music business. The post-Nirvana “sign-any-loud-quiet-loud band” trend had gone its course. “Baby Bands" – good bands with no fans – were given grown up budgets. They made great records… and then they were dropped. And then there was this thing called the internet looming.

Working with Daniel were Mark Linkous and Alan Weatherhead, two of the truly numinous artists I’ve worked with. The first SparkleHorse record Vivadixiesubmarinetransmissionplot, helped put Sound of Music and Richmond on the world indie rock map, though in America they were mostly only known to other musicians. I remember on a ferry to Ireland in 1997, they were showing a special on SparkleHorse on VH1 on the big screen; I couldn’t believe it. Mark went on to influence the likes of Radiohead, Björk, and Deus.

Alan Weatherhead started out living in the basement as an intern. His intuitive musical style and quiet demeanor fit in perfectly with our “family style“ production approach. Alan was quickly playing on and recording records for Camper Van Beethoven [Tape Op #132], Joan Osborne, and Nina Persson of the Cardigans. Alan was our "fifth Beatle.” David Lowery [Camper Van Beethoven, Cracker] and Mark’s star power and artistic vision brought people in, and Alan and I made the records actually happen. And then IT happened.

The days after Sept 11 were full of chaos. The CMJ convention was supposed to be the next weekend, with hundreds of bands into New York City to play. I was supposed to represent Sound of Music at the first ever SXSW in Amsterdam, but all flights were grounded. No one, including the music business, knew what was going to happen. I don’t know how much Daniel knew about what was going on in the “real world.” I know that when flights resumed, he showed up at the Austin airport for his flight to Richmond with no ID or money. After that was sorted out, there was no one on his flight, so he was bumped up to first class. Somehow while changing planes, even with all the extra security, he managed to wander into the pilots' lounge. Finally, safe at the studio, recording began, interrupted by frequent trips to buy comic books and donuts – and his favorite, Mountain Dew .

The CD they made, with drummer Miguel Urbiztondo, was called Fear Yourself. When it was released, no less than David Bowie said of it, "This will have to be one of my favorite albums of the year so far. All of the Johnston traits are here in abundance. Beautiful melodies, fine if painful lyrics, and a searching poignancy that clutches the heart like iced velvet." Daniel also liked the record. According to Alan, Daniel said, “This my favorite record. It sounds like The Beatles AND The Beach Boys, with me in the band!” After he left, Daniel would call the studio long distance, sometimes at night after his parents went to bed, to talk to Mark.

The attack on 9-11 hit the music business like a sonic boom. In his excellent book Perfecting Sound Forever author Greg Milner quotes engineer Charles Dye; “What really kicked it into overdrive [changes at labels] was 9-11. Every business out of New York froze. The record industry stopped production on all projects. When they began production again, they had smaller budgets and fewer artists.” It makes me smile to think of Daniel flying first class, as the last of the Mixerman-style glory.

I was glad I was at a show when I got the news about his death. As it spread through the room, the opening band was finishing up and the singer said, “We’ve got some shit out there... you know… on the internet." I was suddenly even sadder. Was that all music was now? Shit on the internet? They didn’t even have a copy of their own “shit“ to buy. Then Toward Space took the stage on the eve of their three week tour to the West Coast and back. When David thanked Daniel, Seyla flashed a big smile, and Ben kicked in with a fill and a blast of feedback, I remembered why we started that studio 25 years ago.

“Lucky Stars

Lucky stars in your eyes”

We love you Daniel

“Paul Leary was also interviewed about producing Daniel Johnston in Tape Op #94."

https://tapeop.com/interviews/94/paul-leary/