THE ERA OF HI-RES DIGITAL AUDIO IS HERE

I’ve been watching the rise of hi-end digital audio recently, and as I put the individual pieces together over the past year or so a picture is emerging that has inspired me to claim that we are entering a new era of hi-res digital music. We are, I believe, at the edge where compressed audio (MP3s, AACs, etc) will be as outmoded as 8-track tapes and new hi-fi consumer playback systems playing uncompressed digital files will soon be the norm. Evidence that we’re entering this era comes from a number of different sources, most of them efforts to get hi-res digital into the market.

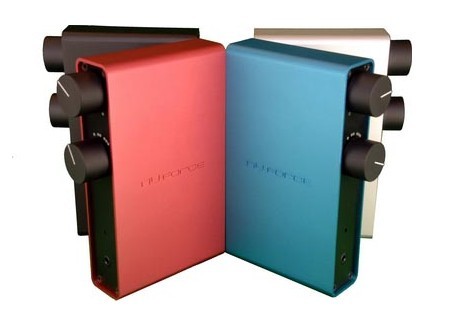

HI-RES PLAYBACK DEVICES

On the device side Neil Young’s PONO system has led the way and has been a great advocacy platform, but Sony has just announced that they’re building hi-res digital playback devices and offering their catalog in hi-res, too. Other commercial devices have recently emerged: Astrel & Kern’s hi-res portable player, a $200 hi-res portable digital player from FiiO, Teac’s affordable hi-res DAC with integrated amplifier, the ubiquity of Peachtree Audio’s integrated amps with hi-res DACs, various DSD players, compact DACs meant to work with portable computers, and the list just goes on. Almost all of these devices are brand new to the market, aimed not just at audiophiles but at listeners of all ages in all areas of musical interest.

To be clear, these players will, of course, be of varying quality, but they are all designed to outperform and/or vastly improve an iPod, laptop or phone. Better clocks, much better D-A converters, better analog stages and headphone amps, better power supplies to run it all. Better playback systems will also play back lower-res files much better, making backward-compatibility with existing digital music libraries not just possible, but better.

EXPENSIVE HEADPHONES, THE GATEWAY DRUG

As we know, on-ear headphones have also become ubiquitously available and - remarkable in a market where theft was the dominant transaction - people are willing to shell out a lot of money for them. While we can groan about the fact that many headphones have become more a fashion statement than a hi-fi investment, the very notion that there is better sound to be had, and that it might cost some money, sends a strong message into a market that was previously dominated by the steal-it-and-screw-it mentality. That’s a big deal. The very availability of expensive headphones is like saying, “Slow down and really focus on the sound for a moment. Just listen.” Anyone who walks into an Apple store today is confronted with a selection of headphones that include stunningly revealing offerings, like Bang & Olufsen’s new B6 headphones (their first headphone offering in over two decades!). Such headphones at Apple Stores make exposure to hi-fidelity experiences a mainstream offering for the first time in a long while.

HI-RES FILES

On the file side, we’re seeing more and more albums being converted to hi-res digital formats, and here’s where the discussion gets really interesting. Neil Young’s PONO format is going to offer a provenance guaranteeing that their catalog of hi-res files derives from direct transfer from studio masters - often analog master tapes. Sony will be offering a similar guarantee, and many smaller labels are now doing the same thing. Hi-res digital sales sites such as HDTracks gather together the hi-res offerings from around the world into an easy-to-use store and offer information like the following:

"The Grateful Dead studio albums were mastered from the original master tapes in Airshow Studio C, Boulder, CO. Transfers were done at 192kHz / 24 Bit from an Ampex ATR with Plangent replay electronics to a Prism ADA-8XR A/D converter into a soundBlade workstation."

Not everyone is going to care that much about the individual pieces of gear used - and Grateful Dead fans have been notoriously struck by wide-spread audiophila - but this kind of information will likely become part of the credits on hi-res digital, because people will soon want to know that they’re buying the best possible file. No one wants a DSD transfer of an MP3, and when possible a direct transfer from original masters will be the thing people want.

But why? The appeal of that direct transfer of a studio master is fascinating, when you think about it in terms of fan appeal rather than audio quality. Music fans have always wanted to be as close to the artists as possible - front row center seats, an autograph, candid interviews, etc... Fans love to be close. And with hi-res digital there is the sense that the listener is in on something intimate, something usually reserved for those lucky enough to enter the sacred sanctuary of the recording studio where the records were made. We can argue about fidelity and hi-res all we like (I’m bracing myself for the comments to follow), but - regardless of whether the digital code has any actual relationship to what happens in the studio - from a marketing perspective music fans want access to their favorite artists and they’ll pay for it! Hi-res digital files might be as close as some of today’s fans can get to feeling like they’ve snipped a lock of hair off of a Beatle.

DELIVERING HI-RES DIGITAL MASTERS

For those of us making records, the game is changing as concerns about forward compatibility are forcing us to think about hi-res digital releases in real terms for all genres. Previously dominated by classical and jazz recordings, I predict that people working on records in all genres will be asked about hi-res compatibility. Audio workers will have much to learn, and there are many angles to examine. Questions like: What will we do when our source files are lo-res? What are best practices for converting between formats? What's the best way to archive our work for future-proofing it? What are the different formats cilents will be demanding? Do I invest in new gear to be ahead of the curve or wait?

Truth be told, as much as I am a big big supporter of the hi-res digital movement, I have a lot to learn about how best to deliver it in the studio. This is one of the reasons I’ve returned to archiving final mixes onto analog tapes that can be converted later. Analog seems endlessly future-proof (Steve Albini more famously agrees).

HI-RES FORMAT WAR - DSD VS. PCM

And, as with all moments of format change (e.g., going to stereo, the introduction of portable tapes, the battle over CD standards, etc), there are competing formats. In this case it seems to be down to DSD (Direct Stream Digital) and PCM (Pulse-Code Modulation). Critics and champions of both formats exist, but for the time being the reality seems to be that we’ll need both because of the need for backward-compatibility with existing digital music libraries which are PCM-based. And there’s much talk of how DSD and PCM play together, the fact that nearly all DAWs operate on PCM platforms, whether one must convert to PCM to edit DSD, and how certain playback devices manage (and even convert between) the two formats. It’s a bit of a mess, but I think the market will suss it all out soon enough - one format likely to win out as VHS did over Beta video.

But I’m not nearly as interested in the details of the format battle as I am in the fact that it’s happening at all. The format battle is another strong indicator that we’re entering into The Hi-Res Digital Era.

POST-FILE LIFESTYLES

Streaming is a likely replacement for file ownership. Hi-res files are big and probably not going to stream effectively any time too soon, but probably sooner than we imagine. The idea that streaming could become a hi-fi experience is very promising for many reasons, and might help bring us around to a place where streaming services are valued as highly as the works that stream through them deserve to be valued. Also, it's important to remember that even a streaming audio file (of whatever quality and resolution) will sound better if handled by a hi-res, hi-quality playback system.

DETRACTORS

There are a number of people who would contend that hi-res digital is a needless ruse, that 16bit/44.1khz CD technology was the pinnacle of what’s needed in digital to get us the music in the best format possible. There are also a slew of double-blind-A-B test that show that people can’t hear a difference between data-compressed audio, CD-quality and hi-res anyways. I really don’t want to engage that discussion but I also know that I must, at least preemptively. So, a the risk of derailing the discussion, let me quickly outline my thoughts on this:

- Most importantly: hi-res digital files formats are only one part of the equation. We need great playback systems, too, and, YES!, CD-quality files can sound amazing on a great player. Much of what will make the Era of Hi-Res Digital wonderful will be the availability of great playback systems and beautifully converted masters and increased awareness of fidelity.

- I am highly suspicious of blind-A-B tests as the end-all investigation (see this for more). I believe that even when we can’t hear something consciously, small differences can affect us on the subconscious level, and significantly, over long periods of time. This is a wholly different take on how aesthetic experiences and our senses work than is supported by the blind-A-B paradigm. It hasn’t been properly tested except for once, and not fully (read this for a description of the study). Such tests are expensive and time consuming, unlike blind-A-B tests whose prevalance might be merely due to convenience and inexpense (the parallel to the MP3 not lost on me!).

- The equipment used in these A-B tests (often a "subject's" personal computer) needs to be revealed, especially the playback systems used because playback systems can mask differences.

- There are many really well respected people out there who believe that there are differences in the time-domain (how sound travels) not the frequency domain (which sounds travel) and that we need further investigation into this area of interest to understand better why more than a few people (and many with expert ears) prefer hi-res digital formats.

Suffice it to say, there is much to investigate going forward and I am broadly asking that people catch their breath, slow down, and begin with a humbler sense that there is still much to learn about digital audio. I also ask that more people openly question the scientific paradigms being employed to test our perception of hi-res digital audio.

IMPLICATIONS

I believe that records should sound amazing and cost a lot of money. I believe the cost of records should have risen with the rate of inflation, not declined inversely. I know that the Big Bad Labels are going to try to sell their back catalog over again in a new format (yes, this has happened before). I also understand that many of the playback products and audio files will come out under the marketing-friendly monicker of Hi-Res Digital and will not meet quality standards (my cheap, plastic record player as a kid said “hi-fidelity” on it, as did many crappily pressed records I owned). Yet I believe that Hi-Res Digital offers the record industry the opportunity to both raise the fidelity experiences for people on a mass scale (just look at HDTV), and I believe that hi-res digital can put a more appropriate price-tag back onto records.

“GET REAL”

Powerful aesthetic experiences move people and can cause people to value what they’re experiencing far more. Three-dimensional, holographic experiences of well-made soundscapes can transport people, absorb them, inspire them, relax them, energize them, fascinate them, raise new questions and ideas - all the good things art is meant to do. Again and again I’ve watched people who’ve never heard great sound enter my mix room and say, “Holy Crap! That’s amazing!” So many close their eyes and sink into the sound, almost instinctively.

As David Lynch said of movies:

“If you’re watching a movie on a phone, you’ll never in a trillion years experience the film. You’ll think you’ve experienced it, but you’ll be cheated. It’s such a sadness that you’d think you’ve seen a film on your fucking telephone. Get real!”

I believe that the same can be said of records and their soundscapes, and to the extent that the introduction of this new breed of accessible hi-res digital audio systems and newly minted hi-res audio files can bring that kind of experience to listeners, I suspect that listeners will, in turn, be far more likely to come to value recorded music as it should be. They might even consider paying for it.

Special thanks to Brad Williams for inspiring and informative late night chats about all this and Alex DeTurk for the hardcore belief in fidelity that spurs me on in these investigatsions.

- Allen Farmelo, October 2, 2013

Allen Farmelo is a producer and engineer. He also founded and directs Butterscotch Records.