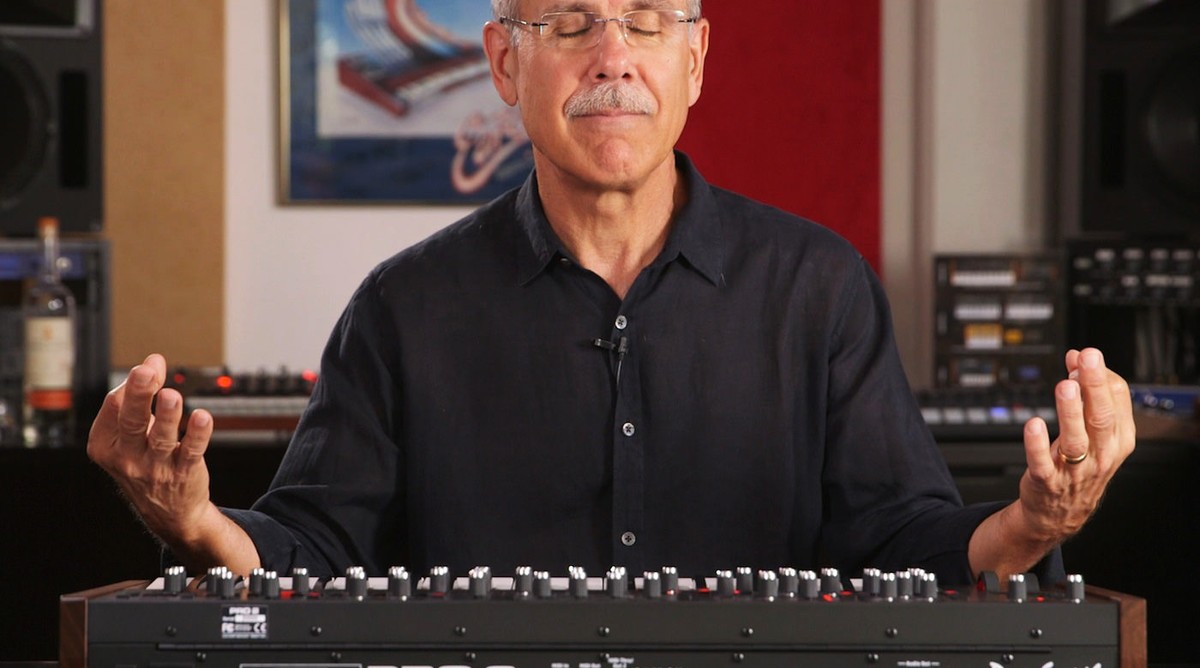

On May 31st, 2022 we lost synthesis pioneer Dave Smith. Tape Op contributor Alex Maiolo wrote this lovey tribute to remember him by.

-GS

Don Buchla, Robert Moog, Tom Oberheim, Delia Derbyshire, Peter Zinovieff, Roger Linn, Hiroaki Nishijima, Tatsuya Takahashi, Daphne Oram - seems like every inventor that moved the ball forward in the world of synthesis had a name that easily identified them. So where did that leave Dave Smith?

Smith may have had, perhaps, the most common name in the English speaking world but he was in no way common. His list of accomplishments in the world of electronic music is massive. He built one of the first iterations of the programmable sequencer, and was very early to the party with music software, but we’ll focus on two problem solvers that can’t be underestimated in that they changed the way music is made, performed and thus how you and I listen to it. Even if his level of geekery is not your cup of tea, if you are reading this publication you are most certainly familiar with his work, even if it’s only one degree removed.

You know the scene: early synthesis scenes are full of fish-eye photos, spaghetti wires, lab coats, and people who look more like professors than rockers. In order to put together a patch a person needed to have a decent understanding of electronics and signal flow, or a lot of patience and imagination, to search for usable happy accidents. Moog, ARP, Roland, Korg, and a few others made some basic models aimed at the hotel bar circuit players who wanted to add a little bit of the future to their cover tune sets, but for the most part it was a nerd’s game. Also, most synths only played a note or two at a time, the exception being so-called “string synths” which actually had more in common with a combo organ.

Dave Smith was a part time music engineer who was making synth accessories, mainly sequencers, which gave birth to his company’s name, Sequential Circuits. He had been bouncing around the idea of a synth with programmable memory slots, but figured Moog, ARP, or Roland would get there first.

That didn’t really happen.

So in 1977, employing his knowledge of nascent microprocessors, he took things into his own hands and, along with John Bowen, brought the Prophet 5 into the world. The importance of this instrument can not be overstated.

Not only could musicians use this machine to play up to five notes at a time, user-programmed patches were instantly recallable. No more fiddling with controls to hopefully get close to the original sound, it was as simple as typing “18,” for the brass stab you had programmed, “12” for the factory pad you had modified for a longer sustain, or “28” for your favorite fat lead. Its closest competition was Yamaha’s CS80, which held two “presets,” cost more, and literally weighed 15 times as much as the P5. Synth pioneer Larry Fast recalls, “In 1978, preparing for an upcoming Peter Gabriel tour I had an opportunity to check out both the new CS-80 and the just-introduced Prophet 5. For me, the Prophet won hands down. It was a hybrid of analog synthesis and computer control, with program memory, in a next generation synthesizer format. It was exactly what I had been waiting for since 1975. I still own that original double digit serial number Rev. 1 instrument.” Along with pop music, it was a staple among soundtrack composers and sound designers, just two more genres where you have undoubtedly heard it at work.

Smith had success with later models too, like the more affordable Prophet 600, and the legendary monophonic touchstone, the Pro One. According to the highly-regarded modular synth developer Grant Richter, the microprocessor of the Pro One “was used to encode an 8 byte sequence of a Buddhist Prayer Wheel as a delay loop into the keyboard scanning routine. So, every time you play a note on a Pro-One you spin a Buddhist Prayer Wheel, and effectively send a prayer to heaven.” Other fun trivia is that Smith would etch non-essential traces into the circuit board, like mandalas, or mushrooms, should anyone ever doubt that these things were made in the San Francisco area.

Had this been the only thing Smith had bestowed upon the world he would have been fit to enter the Pantheon, along with Moog, Buchla, Pearlman, and the other gods, but his second first was right around the corner. Up until 1981, synths could barely “talk” to each other. There were basic ways to synch drum machines, and simple methods for connecting one music device to another, but that often involved converting one maker’s method to another’s with still another maker’s interface. Smith decided a standard, worldwide protocol was needed so instruments from every manufacturer could communicate. This meant anything from start/stop information to patch changes; note length to volume, and well as commands nobody had thought of yet. The code would have to accommodate that too. After consulting with Tom Oberheim, and Roland's Ikutaro Kakehashi He presented his idea for USI (Universal Synthesizer Interface to the Audio Engineering Society. Soon, after a few tweaks, in 1983 it was presented to the world as Musical Instrument Digital Interface, aka MIDI. Modern computers don’t even remotely resemble what we used in the ‘80s, and yet 40 years on, we are still using MIDI. This is how we connect laptops to synths, drum machines to virtual drum machines, controllers, pads, MPCs to digital workstations. It has been modified to allow acoustic instruments control electronic ones, and to make electronic ones control devices that percussively strike things in the terrestrial world.

Yamaha’s DX7 and various Roland products would also make massive sonic marks but, for awhile, only hairstyles defined the decade more than the Prophet 5’s sound. It is fair to say the P5 ushered in “80’s music” as we know it, and MIDI expanded it to the point that there could even be, a Frankie Goes To Hollywood, Heaven 17, Depeche Mode, Duran Duran, Human League, Thomas Dolby, Tears For Fears, as we think of them, or really a new romantic period at all. Without it hip hop wouldn’t be the same. There effectively would have been no techno explosion in Detroit, which along with Kraftwerk, gave birth to pretty much anything you have danced to in a club since. Every polyphonic synth with presets that came after it contains the DNA of the Prophet 5 and MIDI.

In 2010, at the last minute, I was asked to interview, on stage, Tom Oberheim, Roger Linn, inventor of the era-defining Linn Drum, and Dave Smith, separately, over the course of an afternoon. Don Buchla and Suzanne Ciani were in the audience. Normally this would have come with a lot of pressure, but I barely had to prepare. I’d had a list of questions for these giants for almost two decades. They were unbelievably kind people, and generous with their stories. All of them had lost their companies to bankruptcy because they had gotten there too soon, before the world caught up. Others became beneficiaries of their expensive R&D, and trial and error. Smith told me how the three regularly met, along with Buchla, in a Bay area coffee shop. Bob Moog had a standing invitation. They called this “The Dead President’s Club” as a self-effacing jab to their lack of economic acumen, which eventually sunk each one of them. As the years rolled on, and interest renewed in classic synths, these pioneers enjoyed a victory lap, and even released new products that referenced their legacy, usually to high acclaim. Their classic instruments are sought after, and continue to fetch high prices.

On May 31st, 2022, Smith joined Bob Moog and Don Buchla in the afterlife. News spread fast in the music world that the remarkable man with the unremarkable name, the person who changed what music sounded like, the Father of MIDI had passed at the young age of 72. Oberheim and Smith had been collaborating on new products.

Occasionally I’d see Smith at a conference discussing what was new. He always had time for people, some of whom awkwardly acted as if they were meeting Paul McCartney or Barack Obama. Smith usually had a bottle of very good tequila handy so, at the end of the day, he could raise a toast with friends, acquaintances, or really whomever was nearby.

I absolutely loathe tequila.

It’s literally the only taste I despise, and yet I couldn’t say no to a toast with this great man. I still have Sequential shot glasses as a memory. Last Thursday, in my studio, fittingly the night before flying to San Francisco, I stood in front of my Pro One, and Six Trak. I admired their almost hilarious combination of futuristic and seemingly Tolkein-inspired fonts. I filled one of the shot glasses with tequila, and threw it back, to honor one of the greatest trailblazers in music technology.

He was, in fact, a prophet.

-Alex Maiolo