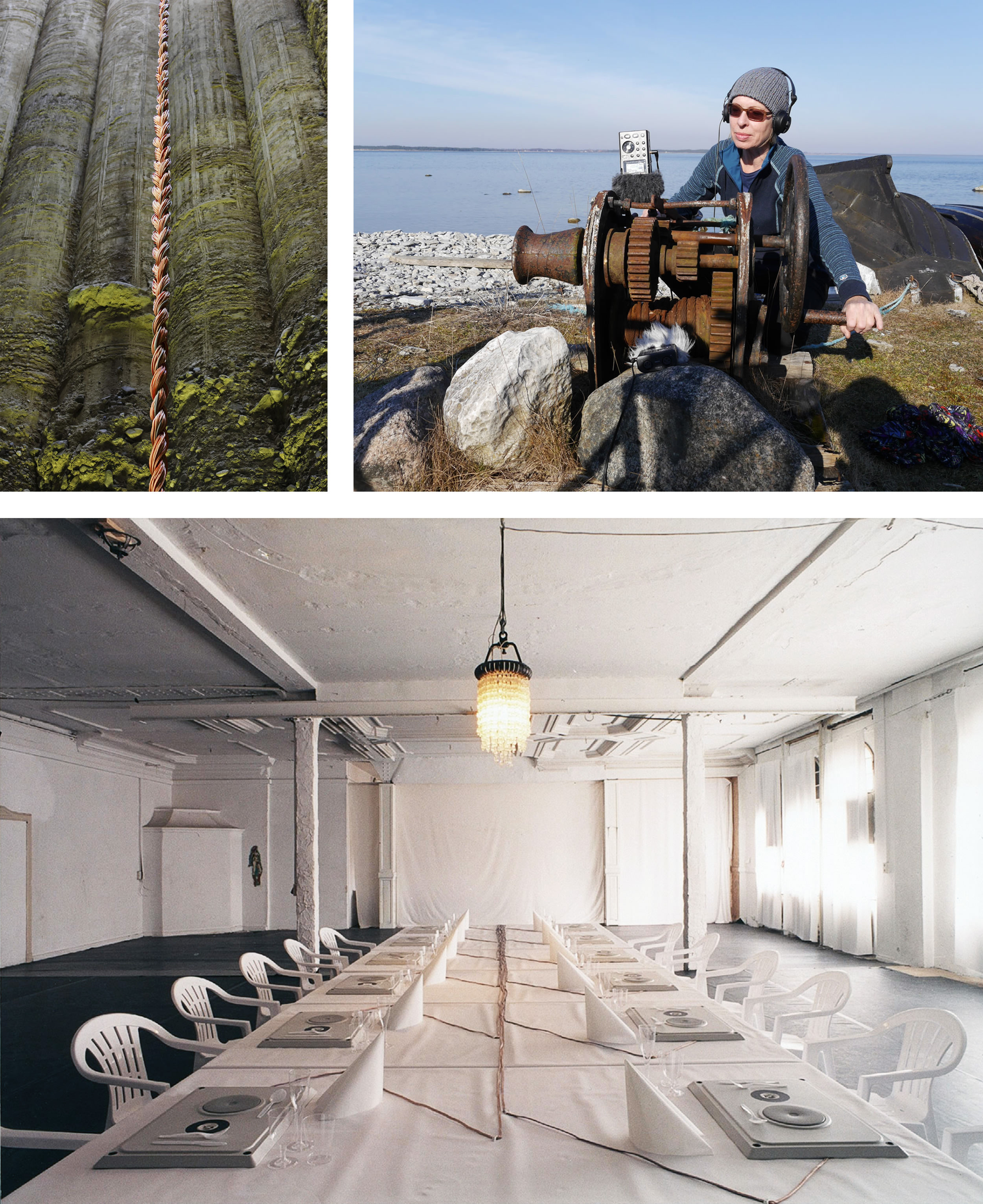

German composer and performance artist Christina Kubisch has created electronic and acoustic music for installations since the '70s. Her work focuses on finding sounds where no one expects, and her experiments with electromagnetic induction as a sound source began in the '80s. In September of 2018, Christina will teach a tempting five-day course at France's CAMP – an arts residency high in the French Pyrenees – on recording, composing, and making installations. Students will work on "connecting sound and space," based on sound material recorded with hydrophones, electromagnetics, and contact microphones "uncovering hidden sounds." A recent split LP with ELEH features her track, "Tesla's Dream," and her double CD collaboration with Annea Lockwood, The Secret Life of the Inaudible, is out soon on Gruenrekorder

The process of presenting a sound installation and making a recording must pose differing audio challenges.

The recording never is just a "recorded" installation. It has its own time. Composing an installation is different from composing a piece of 60 minutes or so, even if there are similarities.

When capturing the feel of an installation, what are your thoughts on listener perspective?

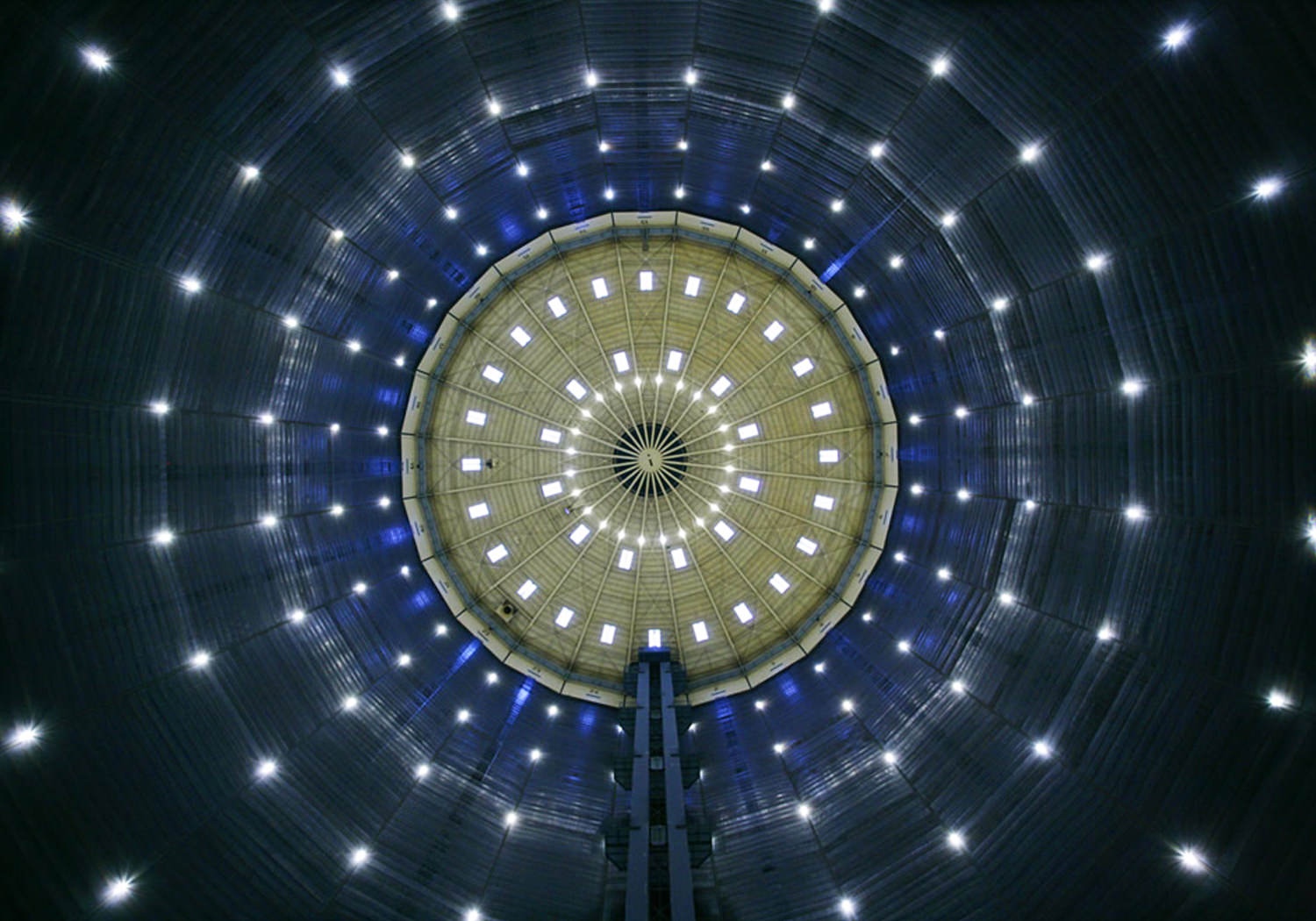

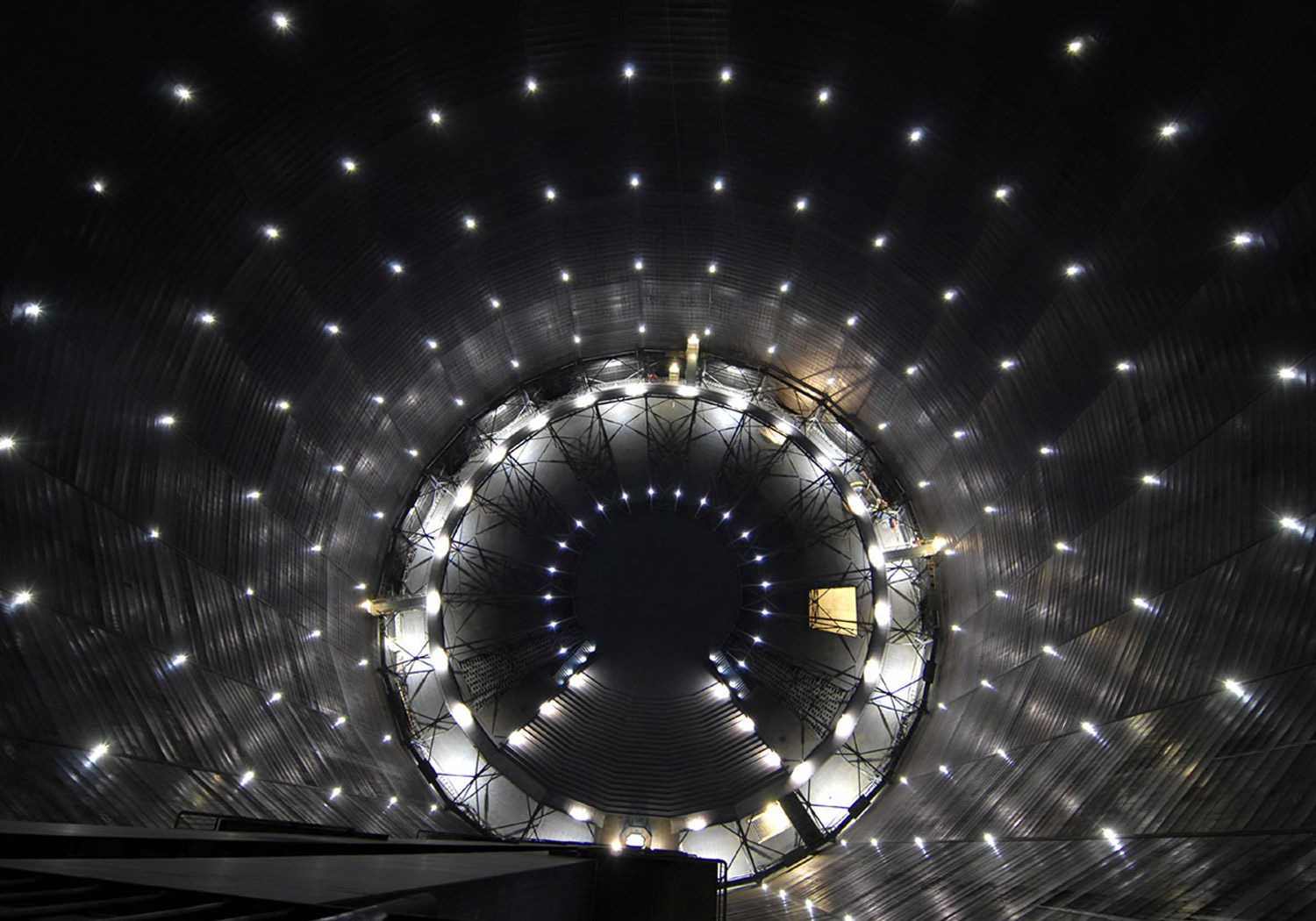

It depends very much on the site specific situation. I like a "placement" that does not mean sitting in a definite row of chairs, but [rather one that] makes it possible to move around (without disturbing others) while listening to different combinations of sounds and speakers in the space from various angles.

How do you capture "hidden sounds"?

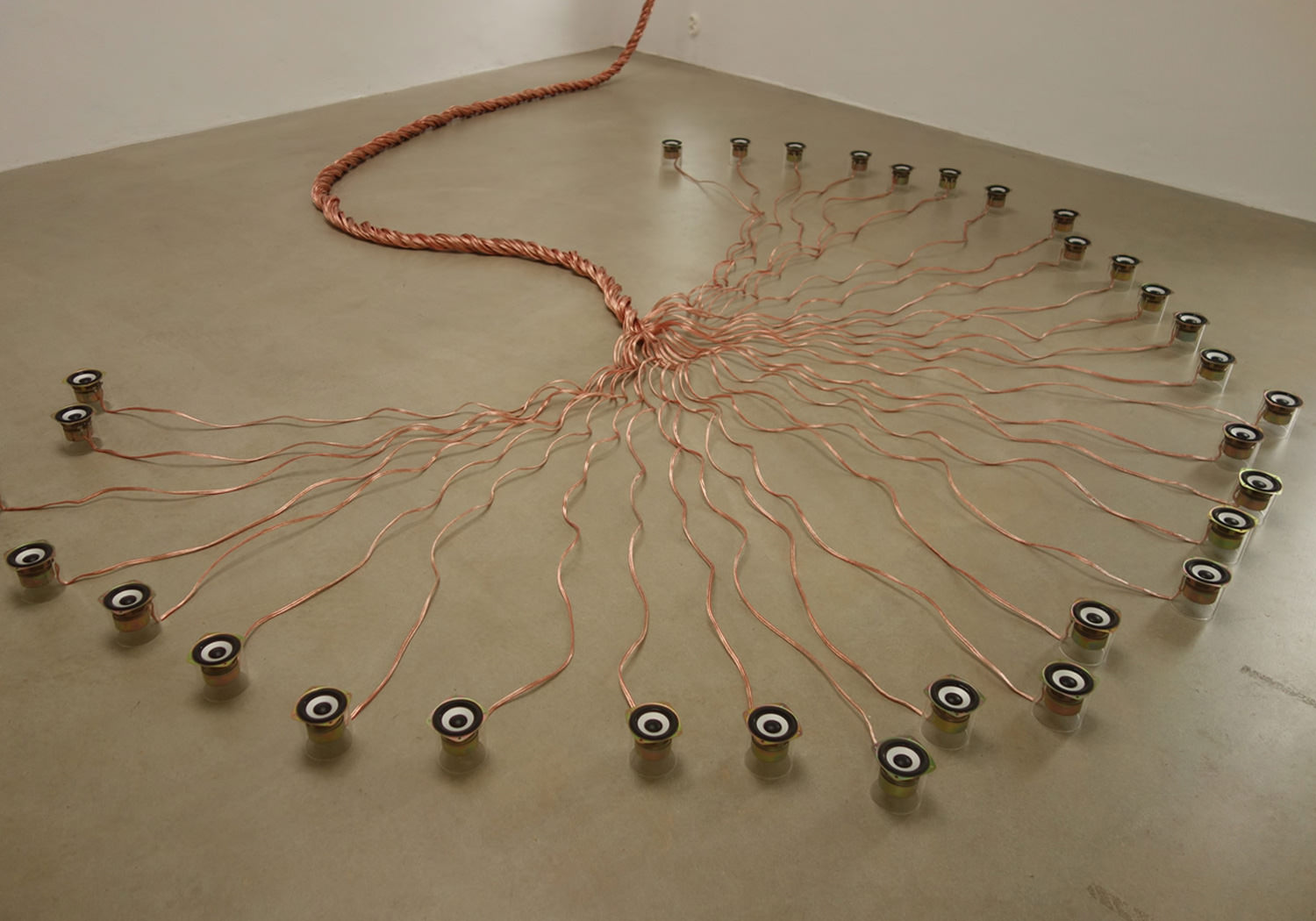

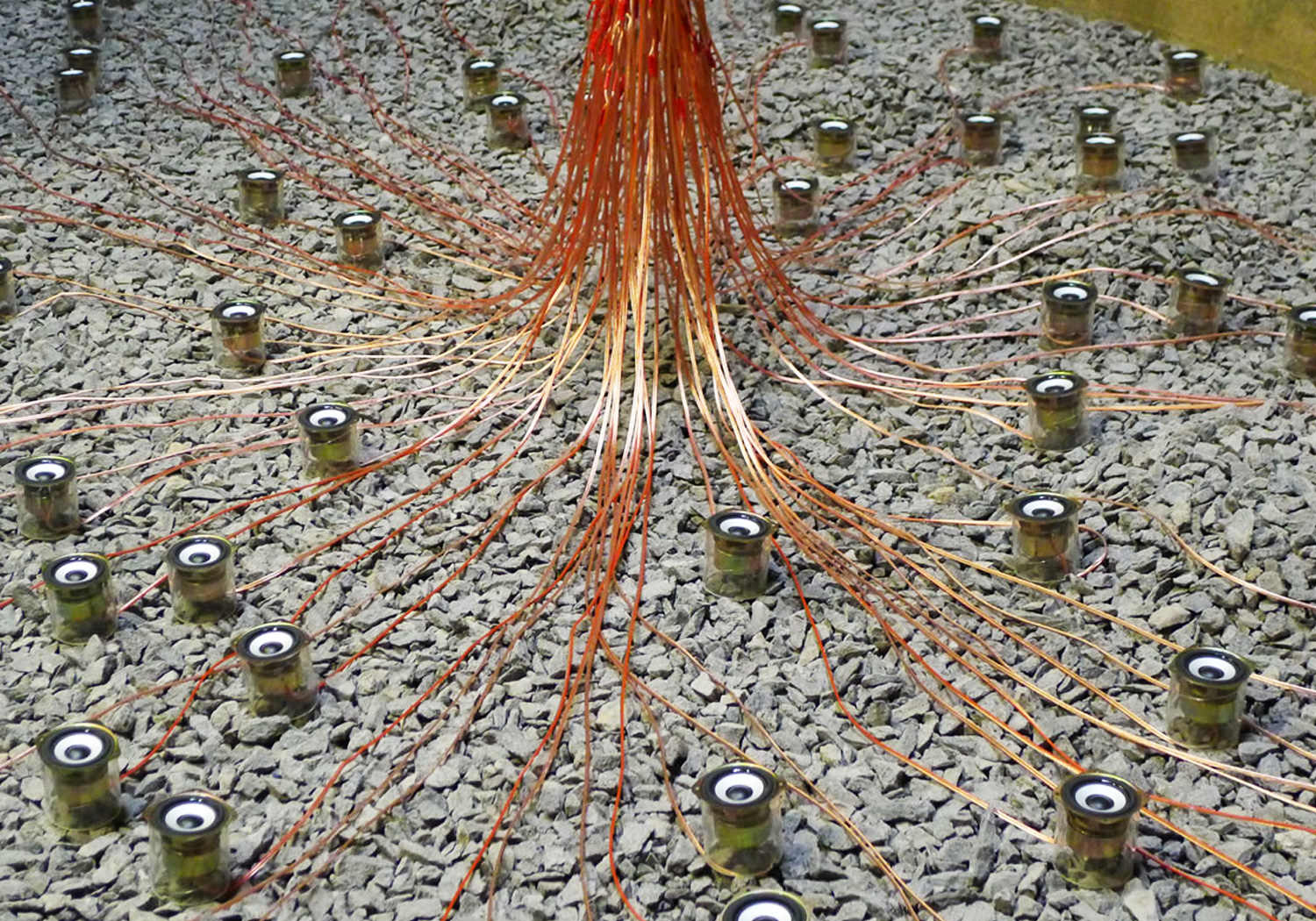

I use equipment which makes audible what you cannot hear usually. The hidden sounds, like electromagnetic waves. Equipment includes [everything from] cheap microphones to sophisticated recording gear, and electromagnetic coils to military hydrophones.

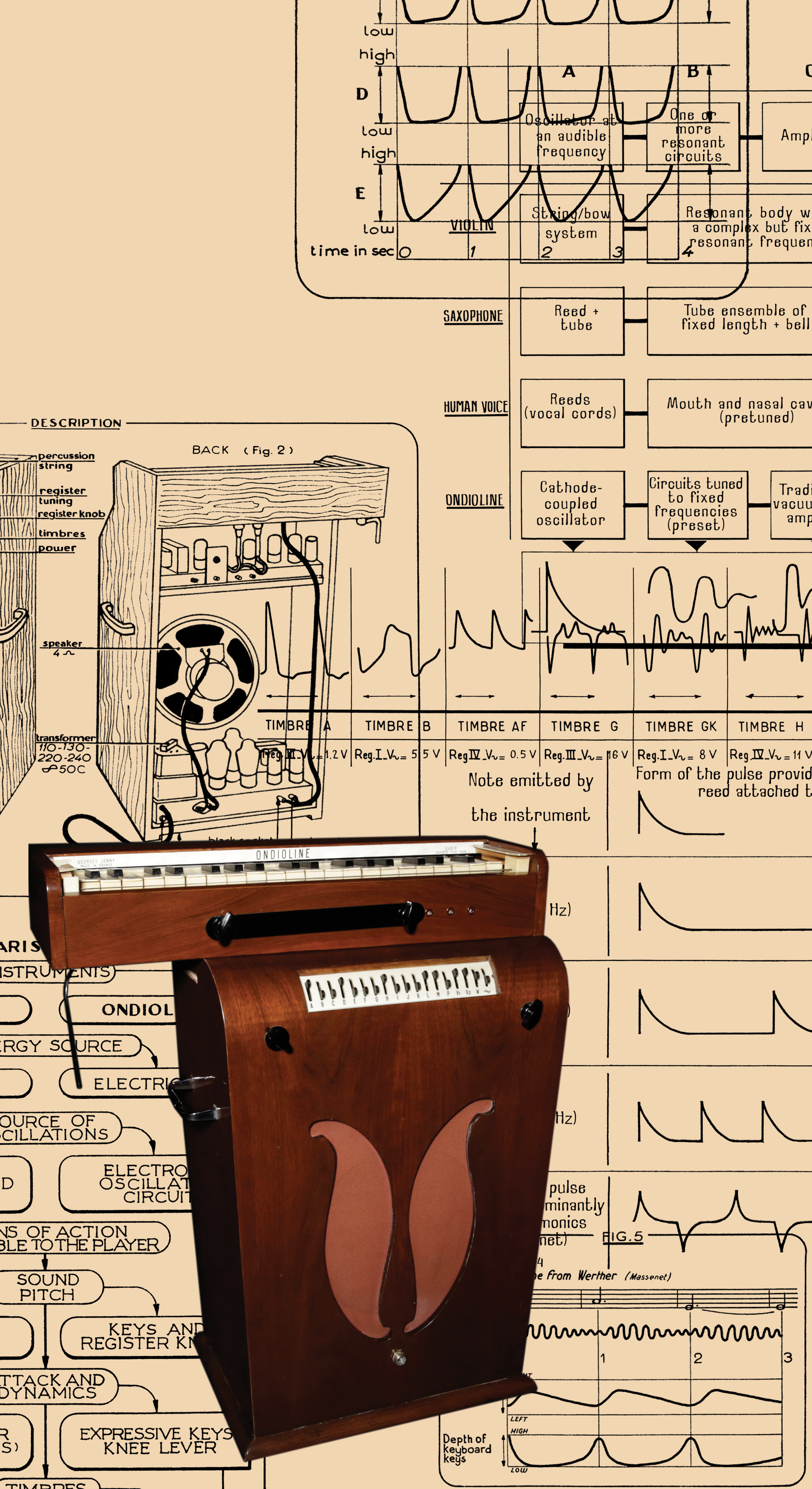

What is the "electromagnetic sound induction system" you use?

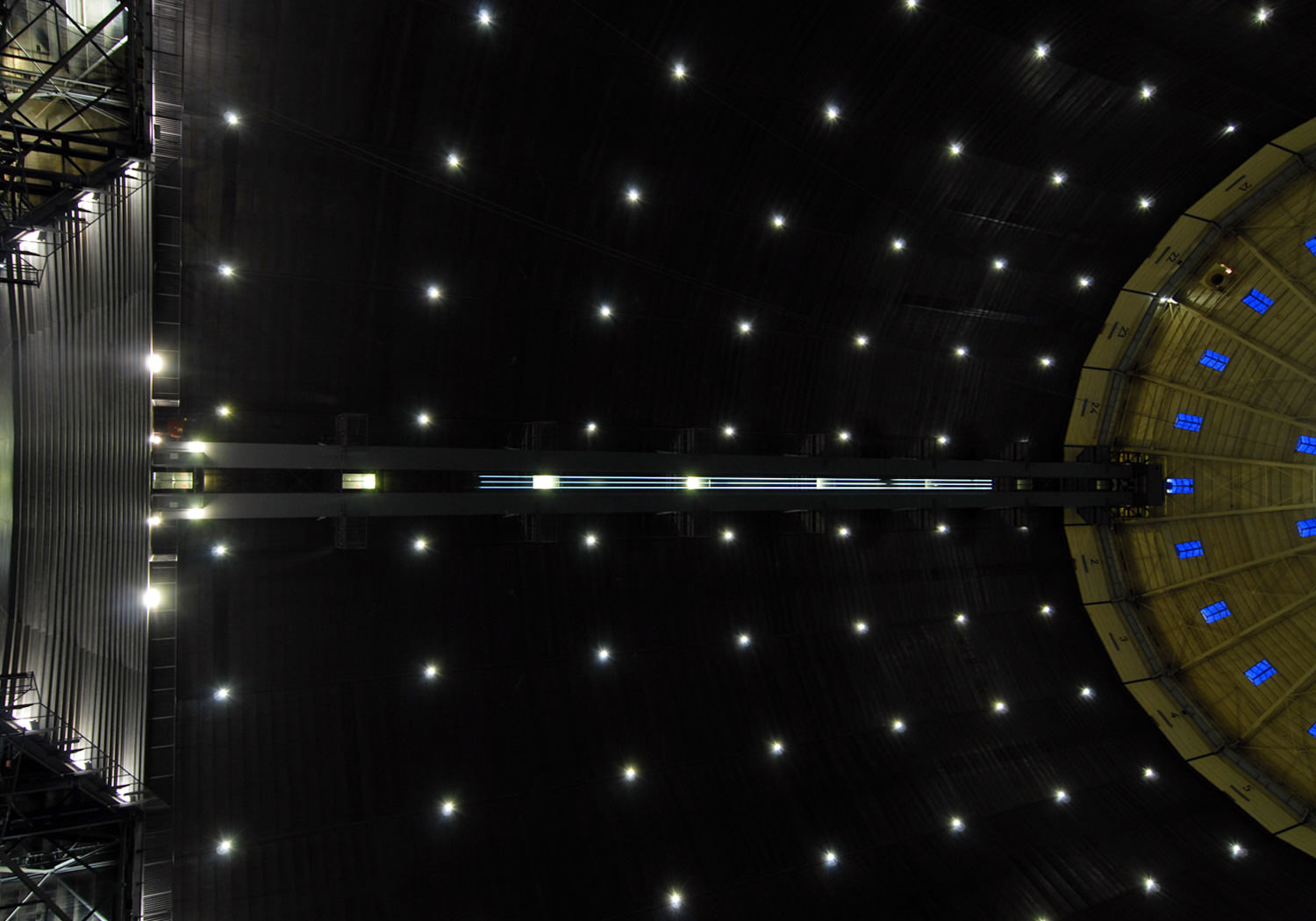

It was discovered around 1830 by Michael Faraday in England. Nikola Tesla continued the investigations, and invented a telephone amplifier in Budapest in 1871. It works like the first electromagnetic cube, which I discovered by chance and used first in 1978. I admire the work of Tesla a lot. My system with the custom-made electromagnetic headphones works like this: every current in an electrical conductor ("wire") generates an electromagnetic field. These currents may be "musical" currents in a sound installation (like the currents running through loudspeaker cables), or they may come from all electrical activity in electrical cabling, power supplies, or any other device. The magnetic component of these fields is picked up directly by sensor coils. After amplification, the signals will be made audible by the speaker systems of the headphones. I pick up everything that surrounds us, from digital signals to old trams, from power lines to a data center, from light advertisements to hidden signals and so on. There are more and more electromagnetic signals around us every day. In my performances, I create some of these sounds by using specially developed magnetic detectors on objects. I discover and translate electromagnetic signals into the audible spectrum in the performance room, walking around with my equipment. I use wireless sound transmission to make the electrical fields audible.

What studio spaces are you currently utilizing?

I had worked many years at the Elektronische Studio der TU Berlin [Technical University of Berlin], while it was directed by Folkmar Hein. When he left, only students of the university were allowed to use it, and the studio has lost its importance as a place of international creation of soundworks. Now I have a small, 4-channel studio by myself. And, as a member of the Akademie der K'nste Berlin, I can use their production studio – a fantastic place – when I need to do larger, multichannel productions.

From listening to some of your works, I assume there is a degree of sound manipulation going on.

I very rarely manipulate a sound electronically. I try to find interesting sounds while investigating the sound sources and how to record them. Sometimes I move the mics or my body while recording. The sound source is always most important to me.

I've noticed a few synthesizers in your compositions. Do you have a favorite?

I have only one, from the '70s. It's an original EMS Synthi AKS. I used it for my last radio play about Hermann Scherchen this year. [Schall und Klang: Die Experimente des Dirigenten Hermann Scherchen]. It's a wonderful instrument.

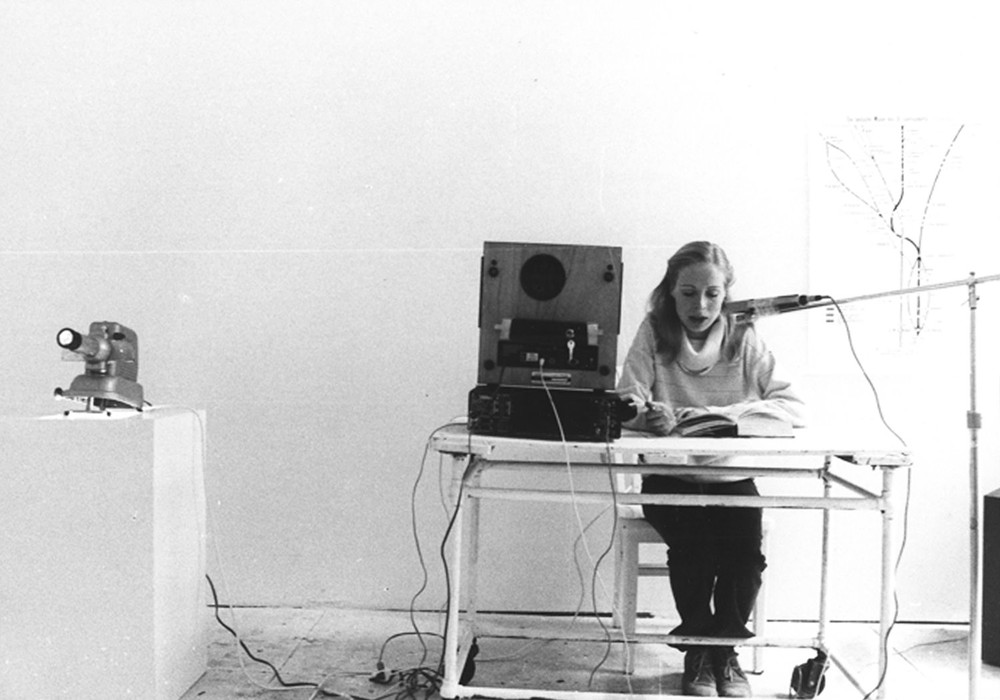

Do you prefer analog or digital recording platforms?

Analog procedures have a different perception of time when I work; the eye is less active, so the ear is more involved. Digital techniques are the reality nowadays, so I use them. I am not nostalgic, but I sometimes miss the physicality of working with tape machines. I just finished a record in collaboration with Annea Lockwood, and we both remembered performances in the late '70s with big heavy Revox [tape] machines. It felt like playing a musical instrument.