I first met Ben Fowler in 2011 while working on a record for a new up-and-coming country artist, Charlie Worsham. I was the assistant engineer during tracking and overdubs, and Ben was going to be mixing. Charlie told me Ben was looking for someone to do mix-prep/edit work for him; I went out to his home mix suite in the country for the “interview,” and we’ve been great friends ever since. Ben cut his teeth working as a staff engineer at New York City’s Power Station in the late ‘80s. During that time he made records with some of music’ s biggest names, including Eric Clapton, Meatloaf, Bad Company, and George Harrison before setting roots in Nashv ille, where he lives and works today. Highly regarded as one of Music City’s best tracking engineers, Ben is also a Grammy Award-winning mixer, with credits including Rascal Flatts, Sara Evans, and Michael McDonald. I would bring my mixes to Ben early on so he could critique them. Among the many things I learned from Ben is this important lesson (in his words): “Mixing is the last performance of a song. If it doesn’t sound great, you’ll be the one to blame. Do whatever it takes to make it sound like a record.” -Gus Berry

How did you end up working at Power Station?

I was in a band in Indiana, and through that we met Tony Bongiovi, who owned Power Station and also produced some of the early Bon Jovi, as well as an early Star Wars thing [MECO's disco version of "Star Wars Theme/Cantina Band"]. We didn't know any producers where we grew up. He owned, arguably, the best studio in the world at that time. I was a musician graduating college, and I applied for a job there, still thinking that I wanted to be a musician. But I thought, "You know, New York is the place to be." I got the call and I was almost like, "I was just kidding." [laughter] I wasn't expecting to get that phone call. I went out and had a quick interview. I'd never been to New York before; it was eye-opening. What a left turn in life, to go from cornfields to the city!

What year was that?

1986. It was a big contrast. The pay was pretty poor; probably much like today. Back then there weren't that many opportunities in music. A thousand people would do it for free, or kill to get that job. I was thrilled to get it. I had to hang onto it, because things were tough and their clients were huge. If you weren't doing your job, or if there were any mistakes, you were gone pretty quick.

Did you have engineering chops before heading out to New York?

No. I studied Music Theory at Ball State University in Indiana. I was always the guy who would get a long guitar cable and walk out into the audience for soundcheck. I would badger the sound guy.

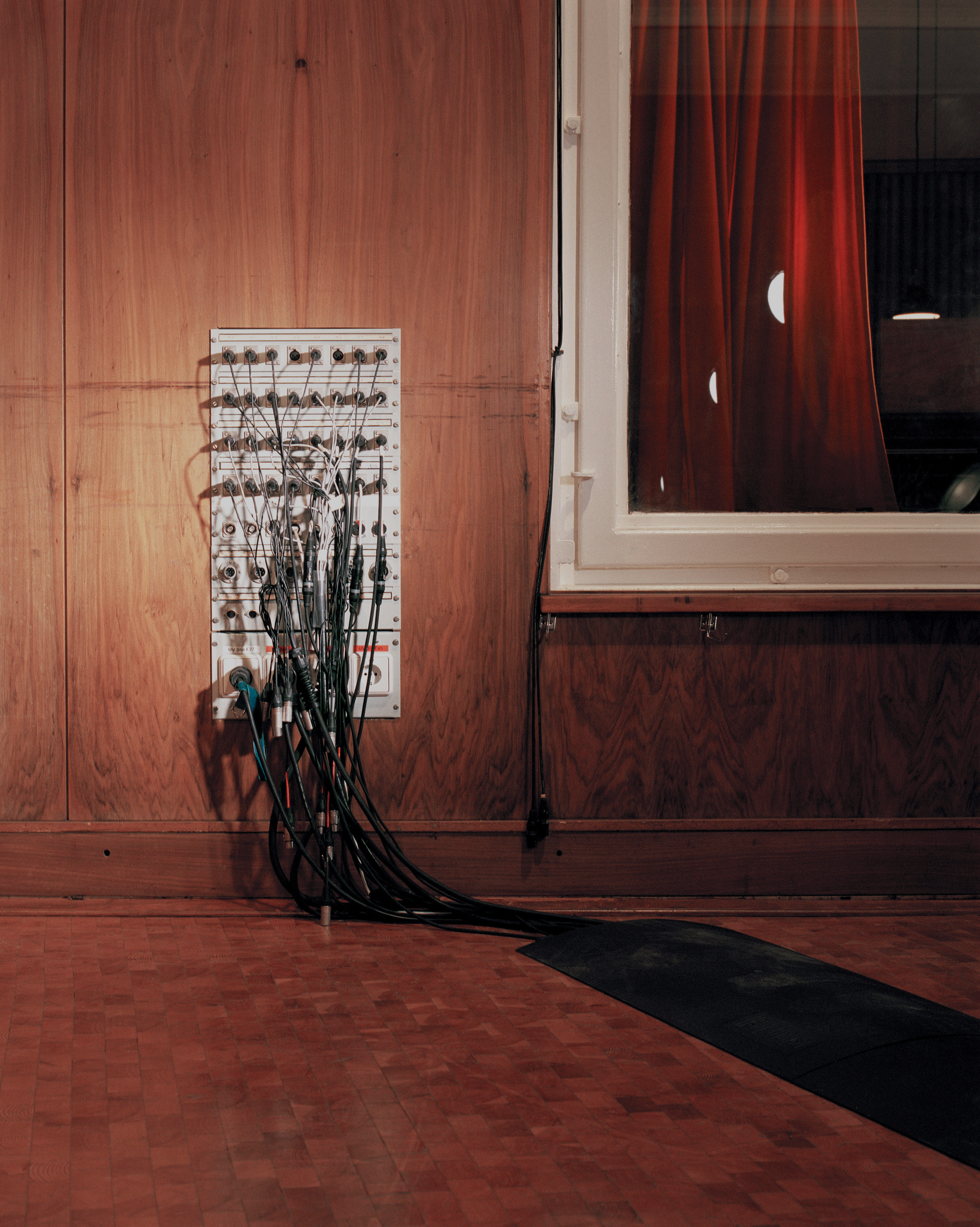

Was Power Station doing the "no real lockouts" deal?

If you wanted to pay for a lockout, you could; but was expensive. Otherwise, there might be a daytime session from 10 to 6, or 10 to 7. We would tear down, tracking setup and all. Then someone else would be up and running by 8 p.m., tracking or getting sounds. There was not much turnover time. The next morning we'd have to recall everything. Measuring mics and consoles. We didn't have digital cameras back then. We were writing on sheets. If you had the night session that ended at eight in the morning, we'd be dead tired trying to document all of that. But people expected it to come back pretty close, and somehow we did. Their clientele was humungous. When I walked in the door, there was Paul McCartney, Cyndi Lauper, Billy Joel, Peter Gabriel [Tape Op #63], and David Bowie. Duran Duran had been recording many of their hits there. It was a great place to land. I got to work on a lot of cool records, like Billy Squier, Bob Mould, and three Eric Clapton albums. I worked with a producer named Russ Titelman. After a certain point, he took me on as his main guy. I started as an assistant engineer, and eventually ended up in the driver's seat for many records.

Did Russ like using that studio?

That was home-base for that era of his career, and that's how we got paired up together. We'd go other places. We might go overdub, and not be in a Power Station room, but that was home-base for him and I. If you were a graduate of Power Station, it had something to it. People would book you. I was the last to go through that. It was neat how they did it. Whoever got hired before you was who you answered to; he answered to the guy right above him, and the guy at the top was thumping, and then it would come all the way down. It kept everybody in order, because the guy above me would get in trouble if my shit wasn't getting done.

Everybody policed each other! [laughter] Who was the person that you worked under, initially?

I worked under Alex Haas and Dave O'Donnell. Dave's had a nice, long career. He's...