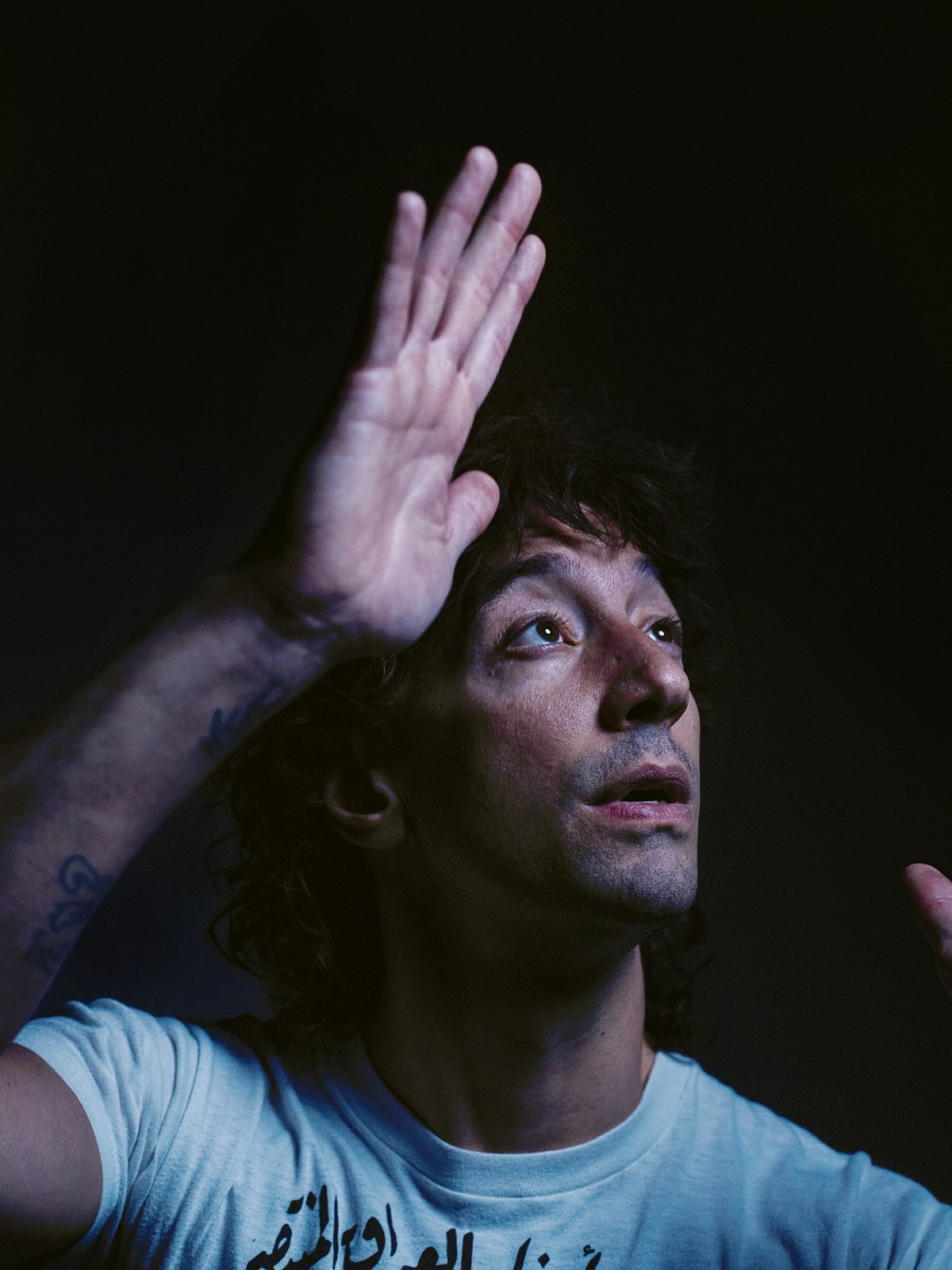

Melodies on Hiatus is a 19-song double album. Was there a concept for you, beyond simply a collection of songs?

No, there wasn't, really. To have that in mind, you have to know that you're going to do that. A year after touring [the previous album] Francis Trouble, I started recording songs. In my head, I was going to put an album out quickly. I thought The Strokes would put their next album out, and then I'd put mine out right afterwards. Then the pandemic happened, and it slowed everything down. If there was a concept, it was that I wanted to deconstruct having a band. Normally, I would make demos. Then I'd get my band, we'd play the songs, and we'd record it. That's how we did Francis Trouble. I was thinking, "What if I did something where it stayed in the demo form? Use drum machines and do it with Gus and me at home? Maybe having a friend or two come over to add parts, and keep it in that in that smaller sound?" There was that idea, but I didn't know I would keep going. I kept having songs that I was excited about, so I wanted to see them through. Some of my favorites are songs that came at the very end.

How did you decide when Melodies… was done?

Well, this is what happened. I always do lyrics last. On the demos I sing words, and sometimes that'll be the title. When I first wrote "Old Man," I was strumming the chords on the voice memo and playing it, and the words "old man" came out. I'd sing the songs with gibberish words. But when I had 20 songs of only that, I had to go in to write the lyrics, and I was thinking, "I'm not going to finish this. I'll throw them away and start again." It seemed too daunting. I tried to get friends in other bands to help me write lyrics. Then I met Simon [Wilcox]. We hit it off, and it was like, "Okay, this seems like it's going to work."

Your collaboration with Simon Wilcox was one that was completely remote for a long time, if not the entire process.

I think somewhere inside she probably would have liked to have kept it to never meeting! Maybe there's a romantic concept in that. [laughs] But yeah, we would just talk: First about the songs, or what I thought my gibberish meant, or what she thought my gibberish meant. I always put titles on them, so maybe it was leaning towards a direction, or she had an idea. We would start talking about life. When I listen back, I think she took both of those things and put them into the songs. We would talk, she would do little batches, I would sing them, and we would go back and forth. She would type out the lyrics on a typewriter – it'd be the only copy – and she would drop it in my mailbox. When I found out they were the only copies, I started taking photos of them because I was worried that if I lost one, they would be gone. It was a unique experience. It's not an easy thing to let go of, or to have someone in your mind there, but it worked. She really captured me.

And this wasn't an old friend. This is a person that you met through mutual friends?

She was close friends with the president of the publishing company, and she said that we would get along. We hit it off. We started talking. Sometimes you meet people and you're able to have an easy conversation into weird, dark places or funny places – not something that you can plan for. You meet someone, and it works or it doesn't.

How is that for you, singing these songs?

Sometimes when I sing, and I'm discovering melodies, I phrase very weird because I'm in the moment. Normally I might not figure out how to keep the phrasing and I'll change it. But she kept some of the phrasing that was strange, or some of the syncopation or rhythm of my words in the melody but keeping some thread through the whole song. That's what helped keep it sounding like me. It's a tightrope walk when I'm writing with someone, especially with something that I'm singing. It was a lot of back and forth. If I didn't feel comfortable, or it didn't feel right with the song, we would go back and forth. We'd have long conversations. We would definitely disagree and agree, and the conversation was open. It wasn't like, "Oh, whatever you want." She pushed back, and that creates a dynamic. That's why you work with someone.

Did you do the majority of this record at your home studio?

I did it in a lot of places. My mom was going through a divorce, and she was staying at a house, so I did some there. Then I rented a house in L.A. because I thought about moving, so I did some there. Then I tracked some in the house I ended up moving to in L.A. – a bunch there because that's where I was during the pandemic. Before, we had worked at Red Bull Music Studios in Santa Monica, [California,] and at a friend's studio that he built. We even did the one with Matt Helders [drummer, Artic Monkeys], Steve Stevens [guitarist], and Nicole Row [bassist] at my publishing company's studio. It was all over the place.

The home recording process is quite different, right?

Doing demos with Gus is one of my favorite parts of writing. I write all the time, doing voice memos and little bits here and there. Then I'll think, "I like these ideas," and I'll start making the song. The two of us together, there's an immediacy in it of discovering stuff. I had this drum machine on my phone that we would use a lot. We'd mic it, and it would sound really weird. I grew up with Guided By Voices [Tape Op #6], so it sounded like that. When I start, I'm trying to create different vibes so that the song can go to where it wants to go, or where I think it should go. As it becomes more of a song, I'll build it out. At first it could be, "Oh, I like these two parts, so we'll do A-B, A-B." Verse chorus, verse chorus. Then I'll see where it gets boring. "Oh, a solo would be good here. How do we intro/outro it? Where are the tones going, guitar-wise and drum-wise?" It develops like that. But it's quicker than in a studio and working with a bunch of people, because in a studio I would play the song and then play it as a band. It would create its own sound that'd be playing throughout the day and then record at night. Here, it was the two of us playing ping pong back and forth, very fast.

Would you go for completion, or would you work on songs and then put them away to come back to?

We would take it as far as it felt good. If it felt like it was in a place and we didn't know where to go, we'd let it sit there and start something new. It's nice being at home, because we can take breaks. I like breaks. I don't like 12-hour sessions, unless we get lost in something and we're discovering. That's fine; I don't notice it. But to forcibly do that much time, I don't like it. We would work for a few hours and get something, and then stop to watch a movie, hang out, or do something like cooking. Then we'd go back and listen to what we had, or start something new. There's no rule. I can beat something to death trying to figure it out, and that'll happen regardless, even with these breaks. But, as we do it, we'll get little sparks, and then we'll build it up and say, "Yeah, that's right." Or, "I fucked it up. Why? Why is it better in a simpler form, and not as good with more instruments?" I keep doing that until the song is done. It's a puzzle like that.

Think about how many records you've heard in your life that you've come to love – and maybe even some of your favorite records of all time – but the first time you heard it, you didn't even get it or like it.

So many. It's crazy. That's what I try to tell people. Some of my favorite bands or favorite songs I probably skipped over, initially. When people ask, "What's your favorite song?" I'll tell them, "It depends on moods." Music can be very powerful. It can align everything in those three minutes. I hear it at another time in a different place, and I know that I felt that – it's always there with me – but I'm not feeling it as strong as I did in that other moment. Maybe a day later, I'll feel it again. That's the problem with writing; it's always moving.

You're capturing moments. In terms of recording, you'll get it then and that's it. You either recorded it or you didn't.

There's definitely a sense of black magic when it comes to recording. I've recorded something and been like, "This sounds so cool. Let's check it out after lunch." We come back, and it doesn't sound as cool anymore. That's what's nice about giving it some time, because the things that are stronger stand out more. We're playing a game: The verse sounds amazing, but it's making the chorus not sound good. We'll make the chorus sound better and now the verse sounds weird.

These musical partnerships, with Gus or Simon, they're so important. You've worked with some other folks over the years, and the big one that comes to mind is Rick Rubin.

Yeah.

I've heard you say that he was hands-on working with The Strokes, but I've also heard that he is very hands-off and just has opinions.

When I've read stuff like that, I feel it's just what people are expecting of a producer and what kind of band you are. If you're a band that can almost produce yourself – you arrange songs together as a band and think and talk about it all – he's great. He gives bigger ideas, and he helps you from getting stuck into corners that don't matter, which allows for less frustration. The things he thinks of are really smart, and he's feeling it from a gut level. We were playing a song, and he said, "The verse is the whole song." We were like, "Shit. I was complicating it." You can't believe it, but then it happens and you're like, "Oh, it is." To rely on someone like that for their opinion is great. It allows you to stay a little more childlike in the creative process. I always felt like he gave us the perfect amount of time and space, things to think about, and things to work on on our own. I never felt unheard or not listened to. He listens to everyone. He's pretty magical for us. I feel lucky that we got to work with him. I think [The Strokes'] The New Abnormal sounds incredible – it sounds like us, but different. During making it, it felt like a new beginning, in the sense that I realized that we had so much more music to write, and maybe our best music left in us. It's almost like the opposite of bands that have been around for a long time. They have trouble in that. I felt, in working with him, like we've just started tapping into everyone's potential and where it could go. That's not a light thing, that's something he helped create.

There's no substitute for the people in the room. I think at Tape Op we do a good job of focusing on not the gear. It's part of it, right? But it's just part of it.

Yeah, but it's not going to make the song better if you have a shitty song. There is a balance with Rick in that, where he uses quality gear, but it never feels like that's part of it. I don't even know how to explain it. Sometimes in finding a tone, the gear can bring something out. That has to be something your engineer is thinking about while you're thinking about the song. We can talk to them, explaining why I feel like it's not hitting how I hear it in my head, and they can be thinking of the gear. What you're trying to bring out has to be the most powerful thing, and everything else is just trying to figure out a way to capture that. We can go into some fancy studio, but it doesn't mean we’re going to sound cool.

What would you be doing if you weren't making music?

Oh man, I don't know. I fell in love with it early on, and I would make music even if I wasn't putting it out. I like cooking, so maybe something in that field. I'm passionate about the idea of what flavors and textures work [together].

I know so many people that are musicians, producers, and engineers that all love to cook.

It's the same thing. Even in putting a song together. I was watching The Beatles: Get Back, and on one of their songs someone said, "It sounds better without the bass. But then it won't have low end." And it's like, "So?" I don't listen to that song and think, "Where's the low end?"

It gets back to that idea that the song is everything.

I find that sometimes some of the best takes have mistakes in them. You just can't hear it because there's something more powerful than perfection. That's something I'm not good at. Other guys in the band are really good at that. Rick Rubin was good at seeing the whole picture. He doesn't care if it took ten minutes or 15 days, if there’re a bunch of mistakes, or if there’re no mistakes. If it doesn't feel right, it's not right. That's some of the charm of what people like about rock bands – and maybe why some last that certain test of time – is that there's a rawness in it, and that feels a little unknown and dangerous. I think people crave that.