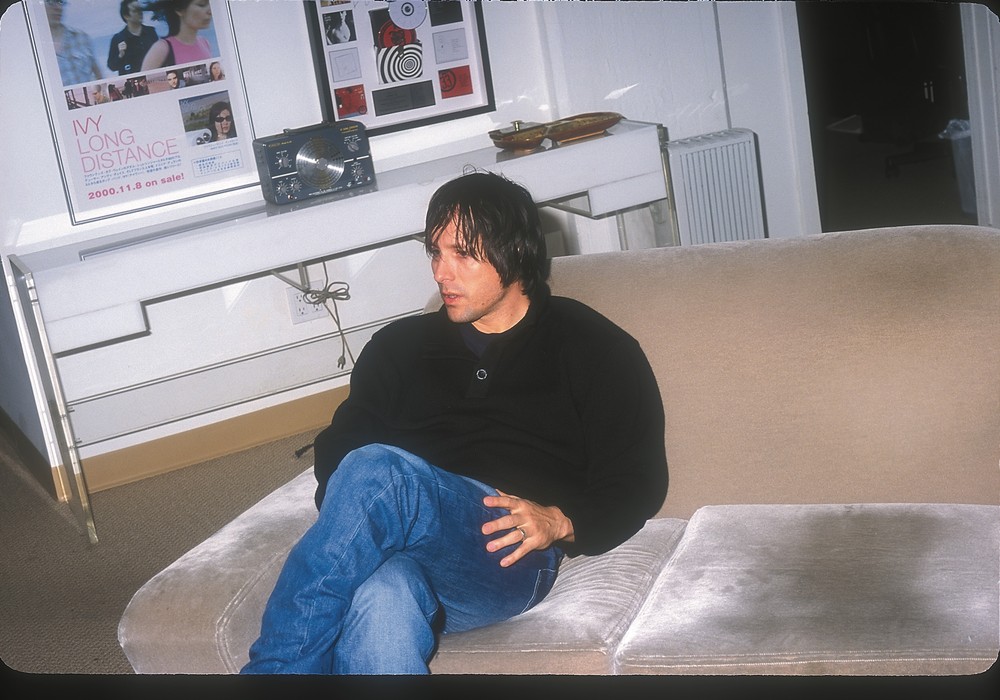

When we met in 1997, you were already recording yourself on 4-track and releasing tapes on your label, Loose Change. What got you into home recording?

There was so much lo-fi home-recorded music in the '90s, and I was really into it. Nirvana was the thing that made me think I could play in a band, but a couple of years later, hearing bands like Guided by Voices [Tape Op #6] and Sebadoh suddenly made recording seem doable and fun. There were no recording studios that I knew of in the town where I grew up, and I didn't know any bands who went to studios. The little bit of a scene that did exist was made up of other people who were inspired by home recording. I don't think any of us thought about studios at that time. You could record on 4-track and have a cassette release, maybe make a 7-inch, and that, when I was in high school, was success. When we met, in the first year of college, I was just beginning to learn about recording studios. I was pretty intimidated.

You attended Purchase College [Westchester County, New York] to major in studio production, right?

Yeah, that was the idea. I didn't have any plans to go to college until a friend went to Purchase for production, and that got my parents nudging me about it. I think they just wanted me out of the house. [laughter]

Did you learn a lot through trial and error, or was the formal training at Purchase more important?

I didn't want to be in school. At Purchase, the studios at the time were mostly using ADAT, though some people were starting to use Pro Tools. I was still into cassettes and tape. I was always looking for old tape machines lying around in a studio closet or something that I could use. I was learning on ADAT, but I wasn't interested in learning anything beyond the basics. Purchase had a few dbx 160s, which only have three knobs, so that was an easy way to learn about compressors. To me, college was more about being social and learning by recording my friends. After college, I didn't even pursue recording for a few years. My energy was more focused on being in bands and figuring out how to go on tour. I don't think I learned that much [at Purchase]. I wish I'd learned more.

Is there anything in particular you regret not learning?

I wish I knew that I would be using Pro Tools every single day. I would have picked up a few more things! [laughs]

Over the years you've played in a lot of bands. How important do you think it is for a producer to also be a musician?

I couldn't imagine doing it any other way. The more instruments I'm familiar with, the easier it is to communicate with people. We learn on the job, too; learning about arranging strings, and instruments that we don't know how to play. We need to learn enough of the language to communicate ideas. It's important that I can jump in the room and play something if I need to. Not in a condescending way…

To have the ability to demonstrate something?

Yeah. It's totally useful.

Do you feel you the need to resist imposing your own aesthetic on a band you're working with?

If they're recording with me, chances are they've probably already heard something I've done, and our aesthetics are in the same ballpark. I try not to impose the ideas or opinions I have, but maybe I'll make a mental list of ideas and then figure out a way to introduce those ideas in a way that doesn't slow down the process or bum anybody out. I don't want to create a situation where people were excited about an idea, and now they're rethinking their whole lives. [laughs]

For Woods recordings, what's the division of labor in the studio between you and Jeremy Earl?

In the beginning, it was mostly Jeremy playing all the instruments and recording himself. As I got involved, that's really how I started getting into recording in a professional way; by assisting Jeremy with the home recordings that he was doing. Our working relationship consisted of me cleaning up his home recordings and figuring out different ways to do that. Those early Woods records are pretty gnarly, but they have a good vibe. I was trying to maintain the vibe while making it not hurt your ears. One thing I'd do was re-record the drums. They wouldn't be to a click track, which was challenging and would require a lot of editing. Jeremy would record drums with just a stereo room mic, five feet or so in front of the kit. So, we'd overdub the kick and snare, then we’d treat his original drum track as the room mic and the new tracks as the close mics. I'd add bass to make the rhythm section a little more mid-fi. Then we started writing songs together, with Jeremy on drums and me on acoustic. We'd write and record the basic tracks in our living room and then overdub.

What were you using to record these tracks?

Usually a Tascam 388, and eventually an Otari 1/2-inch, 8-track, then dumped into Pro Tools. If you look at the Woods discography, it's a clear representation of my chops progressing. On those early records I didn't know what I was doing, but "not knowing what you're doing" was also our mission statement back then.

You have either produced or co-produced most of your own work. Would Woods ever consider hiring an outside engineer?

We've done a few sessions with engineers, but we prefer to have it just be the band in the studio, with me engineering and all of us switching instruments from song to song.

Is that because it's easier and faster to do it yourself, or because you're a perfectionist?

It's easier and faster for the way Woods works. We have such a shorthand with each other, and we work quickly. There are a few engineers I've worked with at different studios that I've developed relationships with, and that can work well, but I do consider myself a producer. If I don't have a relationship with an engineer, it's easier for me to say, "I'll engineer this." So yeah, maybe I'm a perfectionist, or maybe just a control freak!

Ha! What's the difference?

Well, it's funny saying "perfectionist," because that implies that I believe the end result will be perfect. Which I definitely do not believe.

Would you ever consider using an outside producer?

I'm not against that at all, but we've never done it in our 15-year career, so what does that say? [laughs]

I think it can be fun to defer to someone else's vision, but if the result of that experiment is that you don't like the record you just made, then what do you do?

It has to be a shared vision between the producer and the artist, in order to hopefully avoid a situation like that. I like working with bands where a member of the band has those natural producer instincts. Those are the records that always turn out a lot better. This goes back to working with Jeremy, because Jeremy is also a producer on those records. He's got a lot of ideas. He adds interesting textures that I wouldn't have thought of. We have similar aesthetics, and whatever our differences are, they're complementary. Collaboration is key. I like opening a session from the day before and saying, "I forgot we did that!" And that’s usually because it really went somewhere different once people were in the room bouncing ideas off of each other.

Have you adjusted fairly well to doing sessions remotely?

I think so. Even without the pandemic, it's common for me to work with overdubs that were recorded at someone's home, or to mix a record without being in the same room as the artist. It's lonely, but it's okay. When you have artists who are competent on Pro Tools or whatever DAW they're using, they can almost be an assistant engineer on a session. It's also great that people can do overdubs at home, especially since Covid. And having people who know how to record themselves and send a string arrangement is helpful. For recording, even just overdubs, I prefer to be in the room having that real time back and forth.

Are you mostly working with digital these days?

For most projects, digital makes the most sense for speed. But if it's a band that's well-rehearsed, and they can record to tape, then we will do that. Sometimes I'll use tape to capture a live moment and then dump it to digital for overdubs. For the Sam Burton record that I did [I Can Go With You / I Am No Moon], all of Sam's vocals and acoustic guitar were live to tape, with the drums in the same room. The arrangements were pretty simple: Just a live band in a room, with me in the control room playing bass. But the majority of the tracking I do is on Pro Tools, and I have a hybrid mixing rig I use to print mixes to tape.

I know you occasionally work in your own home studio, but you mostly freelance at various studios around L.A. and Brooklyn. How long does it generally take to acclimate to a new studio?

The way I used to go about it was the first day I'd be setting up, and maybe I'd do some tracking in the evening. I read interviews with engineers who would spend days getting drum sounds, and I thought that was how you did it. But now I feel comfortable enough in almost any studio situation to get started as quickly as possible. It doesn't have to be an amazing studio, just one that's set up in an intuitive way so I can start recording within a few hours, if not immediately.

I don't think everybody can do that.

Before I started working at professional studios, I had a home studio. Once I made the jump to other studios, I got into some situations where I was patching a compressor, sweating, thinking, "There's a client here, and I don't know how to do any of this shit!" My home studio was wired in very specific ways that only I understood. But after years of throwing myself in different studio situations, I can wing it. It's great to get somewhere a few hours early so I can make sure all the mics are roughly in place, get a signal, and get the headphones working. Sometimes, here in L.A., I'll take a smaller job or I’ll bring a personal project to a studio to try it out. Maybe I’ll do overdubs there, and get acclimated. Meet the house engineer and see where the good coffee shops are. There's no shortage of studios here in L.A.

What's your ideal studio environment to walk into cold?

A clean studio, with no gear that I don't want to use. I walk in, and there aren't a million choices for everything.

No broken chord organs laying around?

I've done a lot of sessions where I get to a studio early, take a bunch of amps and unnecessary gear, and hide them in a closet. The ideal situation is a place where there's already a house kit mic'd up; even if it's not exactly how I would mic it, it helps if it’s in the ballpark. That way I can get going pretty quickly. I can make adjustments while the drummer is warming up, or while the band's learning the song. That's when I apply my own personal taste and mic'ing preferences. Expediency is a big thing for me. I like capturing ideas right away, where the band isn't waiting around all day and getting tired. Ideally, the situation you want to walk into is one that the band would want to walk into. Where people gravitate towards instruments and start playing something. I try to create a space that invites that; where they get in and they want to start playing music.

You're very expedient, but once the work is happening, I've never seen you be careless, and I never got the feeling you were rushing.

It's a fine line. I want to work quickly enough where I'm still getting quality performances, but not getting diminishing returns. I focus on keeping a session moving, and if someone has an idea, we can try it, but it's understood that we're not going to spend all day chasing this thing. I like to work quickly enough that there's momentum, and then that affords us time to fuck around.

It's been said that a producer also needs to be an amateur psychologist. How do you handle those tensions when you're working with a band?

Having a studio dog helps ease tensions! Anything that can get someone out of their head and can help them gain some perspective. Sometimes we just have to take a break, especially if people are getting hung up on something. But I like to hear everyone out, determine what people are getting hung up on, and see if it's something that needs to be addressed or just given space. I don't like to stop a session just because someone's in a bad mood, but sometimes I have to. It depends on who's in a bad mood! It's important to have a vision of what we're going for, move towards it, and be prepared for it. But, at the same time, I need to be totally open to letting it go somewhere else. That's why I think doing pre-production is so important.

I've found that different people define "pre-production" quite differently.

So many people write as they're recording these days, so maybe pre-production isn't really a thing anymore. For me, it can be something as simple as me going to the practice space and sitting in for rehearsals. Or it could include getting together at someone's home to make dinner, listen to records, listen to demos, talk about what we like and don't like, and focus in on the shared vision. That way we're on the journey together. It's almost like trying to have a truncated version of what it would be like being in a band together for a month. I'm not just a voice in the headphones bossing people around. We're all on the same team, working towards a goal. And then, in that context, maybe I do have some suggestions about song structure or chord voicings. The main idea is to do some prep work so we're not wasting time and money in the studio.

For James & The Giants, you asked to be part of the mastering process, and asked to be put in touch with the mastering engineer. Adam [Gonsalves] at Telegraph Mastering told me that this has become quite common.

I do think it's important to communicate with the mastering engineer. For a while, I didn't think of myself as a mixer, even though I'd mixed plenty of music. I made a choice at the beginning of the pandemic to commit to upping my mixing game, which was perfect timing. During the pandemic I was mostly getting mixing jobs, and part of that was getting better at communicating with mastering engineers so that I understood the whole process. Knowing as much as I can about the end result can inform what I do the next time I'm recording. Even thinking differently about compression and EQ. If I have a relationship with a mastering engineer, and I have a good idea about what they're going to do, it affects what I might do, or will at least make me more deliberate with my choices.

You've recorded music that ended up being mixed by someone else. Is it difficult to hand it over?

No, I can totally hand it over. It's just part of the process these days, especially if I know in advance that I will not be mixing the project; because, while it won't drastically affect the way I record something, I might provide more options for whoever is going to ultimately mix it.

You probably label things better.

For sure. I'll also add a few more drum mics, even if I'm muting them. If I don't know the style of the person who will be mixing, and I have to assume that maybe they don't want a minimal mic setup. But if I'm not mixing it, I turn it over and stay out of the way. With the exception of Woods, these aren't my records. It's not my name on it, so I don't have to answer for it. When I'm working on it though, I can sometimes feel like it's mine. Not in an egocentric way, but in a responsibility way. I want it to be as good as it can be, but once I've done as much as I can I let it go. I'm not going to be the one touring it for two years.

You mixed, but did not record, the King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard [Tape Op #149] album, Flying Microtonal Banana.

They wrote that album with guitars modded for microtonal tunings and recorded it themselves. It's crazy. I love them. There were two drum sets, but with only mono, premixed drum tracks for each. To try to get the snare to cut through a little more, I went through one of the tracks, chopped out every snare hit, and had it trigger a snare sample I'd made. I remember they sent me that while I was on tour, and I started mixing it on headphones in the van. I spent time getting to know it, setting up the Pro Tools sessions, and making rough mixes. It was pretty fun. What a band!

Do you generally mix in headphones?

No. I mix on ProAc SM100s and [Yamaha] NS-10s, but I also always check on my Sennheiser HD 600s because I know them well. If I'm bouncing between studios and different rooms, those headphones are my constant. They've been with me for ten years. If I can make it sound good in those headphones, I know I'm in the ballpark. I'm happiest with my mixes when I'm constantly switching between speakers and headphones – maybe I’ll do a quick earbud listen – and repeat.

I don't nitpick or micromanage the way I used to in the studio, which I think is something that happens to everybody when they've made enough records to know which arguments are ultimately not going to matter in the long run.

Totally. Before I learned how to record, back when I was just playing in bands, I would be over the shoulder of whoever was at the board. And for what? The perfect tambourine volume? It's not that I want to be dismissive of nitpicking. I've been there. I'll indulge nitpicking, because I want people to be excited about the record and be happy to play it for their friends and, hopefully, the world. But sometimes it can go too far. You only really know this after you've done it enough. It comes from experience, and the only way to get there is learning to let things go. It's healthy. Some of the more established bands I have worked with are the least nitpicky.

How did you end up getting hooked up with Panoramic House?

I had heard about that studio for so long, but when I moved to L.A., Nick [Rattigan] from Current Joys mentioned it as a place to go. Jeremy had mentioned it too, for Woods. I did two records there about a month apart: Current Joys' Voyager and Woods' Strange to Explain. The studio has a great vibe. I love the drum sounds I get there, especially on the room mics. When we were driving up to do the Current Joys record, we were listening to a ton of music – Bruce Springsteen, The Clash – and then we put on [The Pixies'] Surfer Rosa and talked about how loud and room-y the drums are on that record. When we arrived at Panoramic, we had that in mind, so we decided to go for a similar drum sound. It was cool to get to the studio, pull up the room mics, and hear right away how good they sounded. It's really a magical room.

There's something alluring about a "destination" studio.

Yeah, I love it. By the time Woods was making [the 2012 album] Bend Beyond, I had amassed enough recording equipment to make a record that wasn't as lo-fi as the early Woods records, and I brought everything to Jeremy's house in upstate New York and set it up like a studio. It was so fun to have all this gear set up. We'd think we were done for the day – we'd crack beers, start making food – and then we'd put on a record and immediately someone would say, "I've got an idea!" Next thing you know, the power's back on, and we were recording something new.

One of my favorite Woods songs, "Weekend Wind," was recorded under those circumstances, as I recall.

Yeah, we had shut everything down for the night, made dinner, and then ended up back in the live room jamming. Jeremy recorded what we did on a cassette. That's why the beginning of that song starts with a cassette recording. Prior to that, it had been a pretty song-based session. But we'd be working on one of those songs and Jeremy would hit play on this tape, and we'd all go, "Ah yeah, that's the vibe!"

But you only had it recorded on cassette?

Only on cassette, yes. We started wondering if we could just release the cassette version, because we were worried that we wouldn't be able to get back to the mindset that led to that jam. Then, two days later, when everything was up and mic'd, and we were recording something else, we decided to try that jam again. I'm so glad we did.

But you initially left it off the record.

It was so long, and we knew we'd have to cut three songs to put it on there, so we left it off. When I heard the album, I was like, "I don't know, man. We've got to include 'Weekend Wind.'"

Was it a tough call to make to omit three songs so late in the process?

Yeah, especially since the record was already mastered. But whenever I'd be working on "Weekend Wind" at home, my wife, Martha, would come in and hear it and ask what it was. I'd proudly say, "This is Woods!" Then we added the horns, and it kept getting better.

Was that the only song on the record that began as a freeform jam?

No. The first song on the record, "Next To You And The Sea," started as a loop that Jeremy made on his iPhone of him and John [Andrews] playing two different keyboards in the control room while we were setting up to work on a different song. We dumped that into Pro Tools, and two hours later we had a full song. That's my favorite thing: To abandon what you're supposed to be working on to follow the excitement and respect the collective "flow state."

You do love a well-organized session, though. Can't that be difficult to reconcile with the "anything goes" approach?

It's not quite "anything goes." As long as songs are getting finished, and it feels like there's an album coming together, then it's just part of the process. Those looser moments usually make a record feel a little more alive and fun to listen to. Being in the studio can be stressful for people, especially if they haven't spent a lot of time in studios. And if some magical shit happens and people are genuinely enthusiastic, it can alleviate a lot of that pressure about getting everything perfect.

Do you have a go-to mic you like to use, or are you good at making whatever you have at hand work? Are there times when an old workhorse like a [Shure] SM7 beats a Neumann?

The SM7 is one of my favorites because it sounds good on a lot of voices, as well as most things I use it on. It's obviously very different from a [Neumann] U 47, so a lot of times it's just situational. Sometimes, for vocals, the singer is live in the room with the band or singing in the control room with the speakers cranked, and we want to get the least amount of bleed or the least amount of cymbal in the vocal mic. An SM7 is great in those situations. Plus, they're cheap and hard to break! I used it on an acoustic guitar on the Woods record we're recording now because it was the closest mic to where I was sitting, and it sounded perfect.

For the Purple Mountains record [Purple Mountains], did the late David [Berman] come in with songs fully fleshed out?

When we first started talking, David sent me a voice memo that had four songs on it: ten minutes of him playing through the songs back-to-back. They were pretty fully formed. David had all the music and chord progressions written, but there were a few songs where we all wrote the chorus together, or where me and Jeremy wrote a bridge and presented it to him. We recorded "Darkness and Cold" last, and David didn't have a chorus for it, so we wrote that together in the room by jamming on it.

David was generally open to ideas?

He was really open to ideas. David was telling us how much he wanted to go on tour, so I wasn't trying to add anything too crazy that he wouldn't be able to play on an acoustic guitar. That was one thing we kept in mind throughout the process. It was more about bringing to life what was already there.

Despite the retrospective context of David's death, it looked, judging by the Instagram photos at the time, like a pretty joyous session.

We had a good flow. We talked a lot ahead of time and then we had three days where it was just me, David, and Jeremy rehearsing the songs together. I feel like we got on the same page.

You mentioned that part of pre-production was talking a lot about music. What sort of things were being referenced?

We talked about which Silver Jews records [David's previous band] were our favorites, sonically speaking. We talked about Johnny Paycheck a lot. When we were rehearsing, David talked a lot about R.E.M.

I have to admit that it's a hard record for me to listen to now, given David's death. I'm sure it's the same for you.

Definitely. But when I listen to the record, I'm also able to go back to the time prior to the tragedy and remember all the hope in the air surrounding it. But yeah, it's hard to listen to. Even listening to the demos was hard. It was clear to me that David was a person going through something very serious.

Yet there are influences that I hear on the record that are not ones that I would necessarily associate with "dark" music, Silver Jews music, or even country music. I hear some Beatles in there.

There were a few Beatles-y things. The harmonica on "Darkness and Cold" was supposed to be like "Please Please Me." Remember, by the time we recorded the record, me and Jeremy had been making a record together at least once a year for about eight years, so there was a lot we didn't really have to talk about. One thing I was a stickler about was I didn't want it to be a "Woods" record, so I was conscious whenever a part sounded too Woods-y. And David said, "If this album sounds like a Woods record with me singing on top, that's totally fine." I was just trying not to impose myself on his legacy.

What kind of Woods-y things were you consciously avoiding?

See, that's the question. Because I don't even know, and I don't know if I did a good job of avoiding it. I don't know if it would have been possible to avoid it!

David had a nickname for you guys.

The Jangle Merchants. I think it had something to do with R.E.M.? When it came time to rehearse a song like "Margaritas at the Mall," David would say, "That's one for the Jangle Merchants."

Did you get any indication David was having a hard time?

Yeah, he was pretty open about it with us. He would stay up all night and sleep late, so we'd work for a few hours in the morning before he'd get there, just doing overdubs, getting sounds, and rehearsing. Then we'd try to have five or six really productive hours with him. David would guide us with comments while also letting us do our thing. In some ways it was the perfect situation, where I have this crew of musicians I trust, and I have this great songwriter at the core of it who trusted us to do the job. I wish we'd gotten to do another one. One time, David was lying under the piano while John [Andrews] was doing a piano overdub. John hadn't even met David at that point. John's on the mic whispering, "Jarvis, he's under the piano." I was on the talk back. I said, "I think he's sleeping. Just play." [laughs] After we recorded the take, David opened his eyes and said, "That was beautiful."