Hi Roman; In regards to your question about Bob, I once worked in a situation with him at Real World. The session was filled with great musicians from around the world, but there was a lack of leadership and the session was floundering despite the talent in the room. Bob entered the room, and after 5 minutes had cut to the source of the best of what was happening, delegated out parts and duties for all the 19 or 20 musicians and we were recording within the next few minutes. He came in and provided the much-needed leadership at a time when it was most needed. -David Bottrill

The letter above, written by engineer/producer David Bottrill, is a concise yet perfect statement describing the greatness that is Canadian-born producer Bob Ezrin. It is likely that a good deal of Tape Op's readers had at one point developed a fixation on a memorable album that was crafted by Ezrin — be it by the likes of KISS, Lou Reed, Alice Cooper or Peter Gabriel. One of his most successful projects is the 1979 magnum-opus that is Pink Floyd's The Wall, a monument of musical storytelling that is a sonic haven of effects and clarity, and conceptually cerebral and entertaining. Ezrin surpasses the concept of being a "producer". From an early age he created massive monsters of music and sound (quite often as a co-writer) like some permanently energetic psychiatrist — with his mind's ultra-sharp eye, he delves deep into the core of a song or idea, and extracts them, arranges, brightens, darkens and colors them, and then puts them through to the public, whose 'third ear' becomes the aural prescription drug that deciphers these sounds and results in the utmost of ultimate listening pleasure. But most importantly, his work contains the guaranteed ability of being able to transfer inspiration unto its eventual listener, and sometimes ended up playing a role as national anthem to one's life at that time. And even via his other ventures, Bob has always strives for the ultimate goal — to connect one person to another. This virtue was rather evident when I was granted the opportunity to chat with him on two occasions at Hollywood's Henson Studios, where he was co-producing the upcoming (from what I had the pleasure of hearing in progress thus far), uber mind-meltingly fantastic Jane's Addiction album. He is a true producer, whose talent, confidence and personality is an astronomical cut above the rest — an orchestrator to the extreme (which goes beyond his mastery of musical orchestras) and involves everyone in any given project to contribute. He would even somewhat control our conversation — already answering and knowing what was going to be asked.

So in the case of projects like Pink Floyd's The Wall or the KISS records. Both had instances of members of not getting along or being "well" per se. How did you go about dealing with conflicts and flakiness? Like Ace Frehley just "not being there"...

Well, we don't want to overplay that. At time of working on Destroyer everyone was completely into it. Everyone was co-operating and trying their very best and certainly there were varying levels of proficiency on their instruments amongst the four players but everybody wanted to succeed. We worked really, really, really hard in rehearsal on that album to make sure that not only did we come up with interesting parts but that the band was capable of playing them well. So contrary to the urban myth that there were a lot of session players on that album — in fact, the band played virtually everything. There are a couple of guitar parts where I had to bring someone else in to help out because Ace was sort of missing in action, but that's all really. The rest of it was the band or me, a few specialists — and of course there was the orchestra. But it was almost completely self-contained. And I think that the band should get some recognition for that because I think when you listen to things like "Detroit Rock City" you hear some powerful confident musicians playing really interesting parts. And, playing well beyond what their previous product had indicated they were capable of. They should get a pat on the back for having done that. And, the only way that they did it was by practicing — being in the rehearsal studio and practicing over and over and over again. We spent weeks in there — 8, 10, 12 hours a day, drilling the material until the band was really comfortable.

And does the rest just become a technical process?

No. Then the rest becomes exactly the opposite. The rest becomes an emotional process. Once you know what you have to do and how you have to do it, you then reach for the feeling. Because far too often, in the studio you go in with material that's just recently been written. You're only partially comfortable with it, if at all, and you spend a good deal of your time trying to play it well. And sometimes, that's sort of "all consuming" and makes it difficult for the player who just experienced the music emotionally. So for most of the music that gets made at studios these days you don't really hear that depth of emotion. And the recordings where you do hear that depth of emotion are either ones that exploded in the studio through a kind of chain reaction of invention and emotion or ones where the band has played them live for long enough that they're comfortable with them, and bring them into the studio and just feel them — play them with all the emotion that they deserve. With the KISS guys, that's what went on — and to a certain extent, the same is true with the [Pink] Floyd guys. We figured out the parts first and practiced, practiced, practiced — and then we recorded them.

The Wall, being a grand concept album, how was it done in terms of linearity? Was it produced in order from the story's beginning to end?

Yes. It was an extremely linear process. It started off with Roger [Waters] having a general concept about alienation and the metaphorical wall between himself and the audience that he considers building.

Did you relate to this concept in any way? Did you go through any bouts of mental wariness and perhaps madness from being in a studio for far too long without seeing daylight?

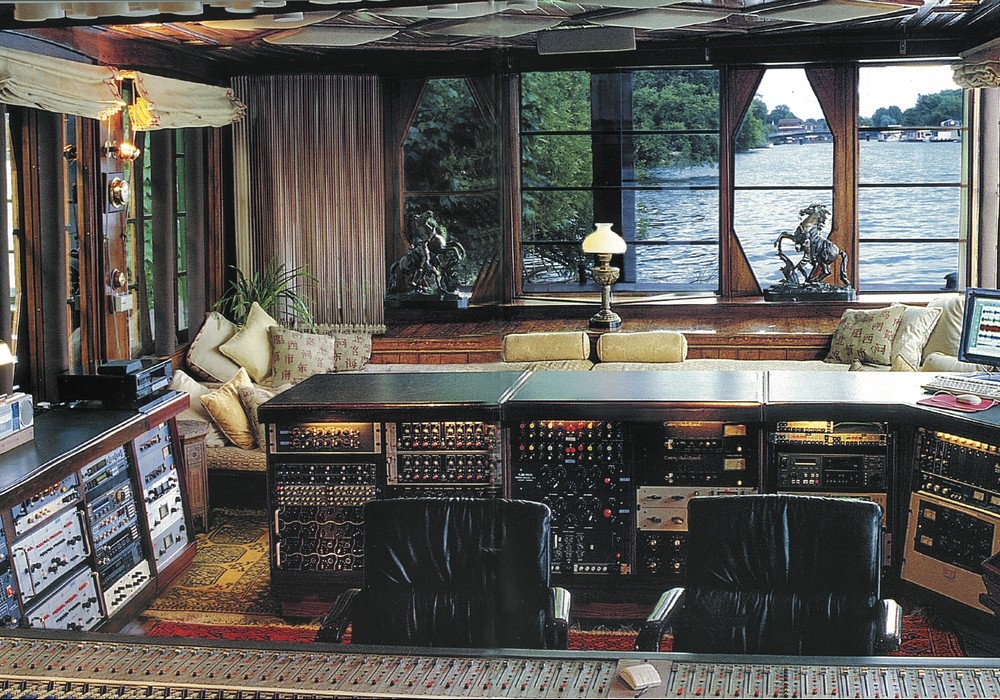

In fact, though we did spend some months in the studio, the settings were always wonderful and the group took very good care of me. So, I did not get cabin fever. On the contrary, I enjoyed the travel and working in different cultures. The project itself, however, was heady, fun, excruciating, mad, brilliant, passionate and draining all at once. It was fraught with the sort...