The year was 1970. Hidden away in a London suburb with a Studer 4-track, Paul McCartney was clandestinely recording the songs that would form his first solo album, McCartney. 5,000 miles across the Atlantic, in Hawthorne, California, nineteen-year-old Emitt Rhodes was similarly ensconced in his parents' garage, busily crafting — on his Ampex 4-track — the songs that would make up his own self-titled solo debut. The resulting Emitt Rhodes was the album Paul should have recorded.

It was, simply put, a pop masterpiece. Working within the considerable technical limitations of his little garage studio, Emitt crafted twelve impeccable and intricately arranged tracks, showcasing an inherent gift for melodic structure and illustrating remarkable restraint, never resorting to excessive embellishment. Every song was an exercise in masterful 4-track economy, and it was evident that each part had been laid to tape with loving care and pure intent. Tight performances, tight production, and wonderfully talented songwriting combined to form a textbook of Lennon-McCartney influenced pop know-how.

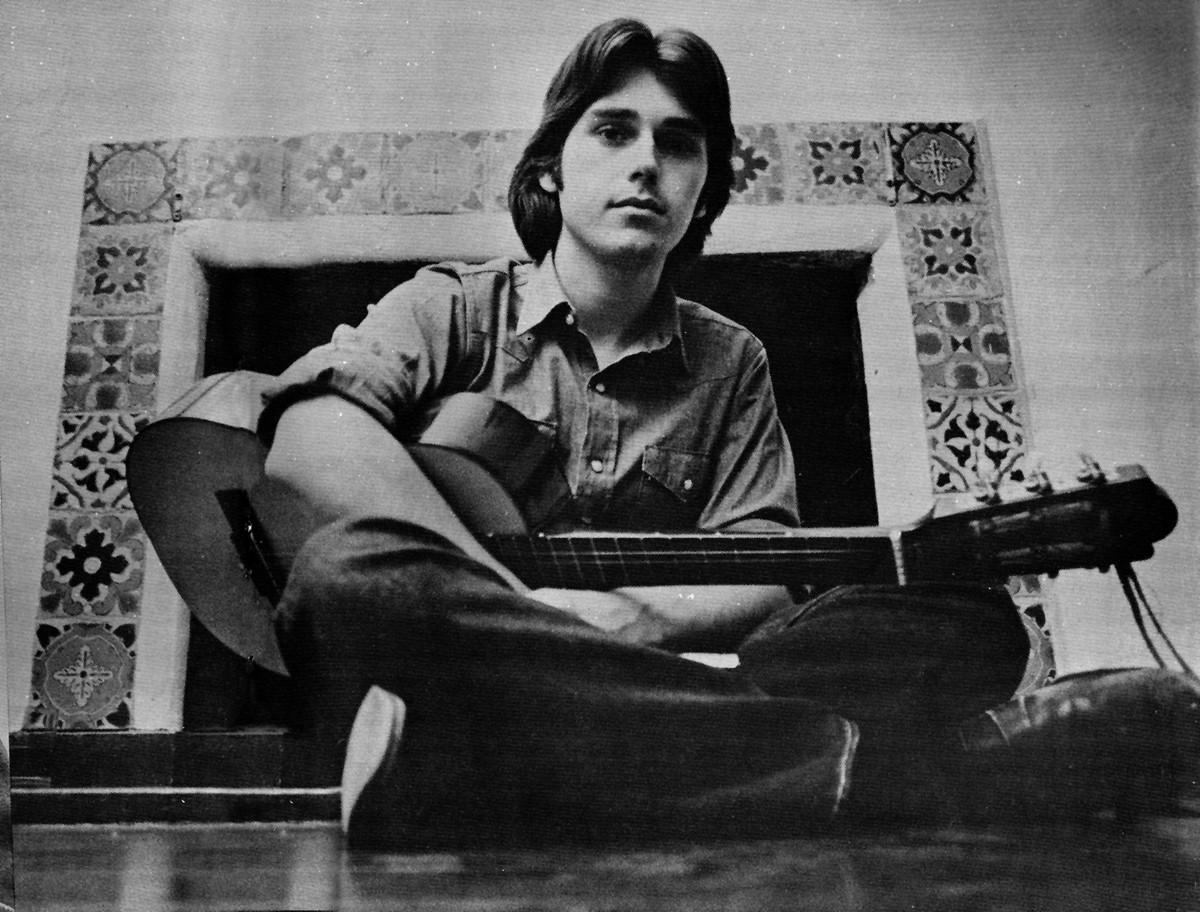

This sense of melody and form had been honed to perfection by the years he spent in the '60s as a member of the L.A.-based Palace Guard and later as front man of The Merry-Go-Round. Though their two year stint resulted in no more than a pair of regional hits — "Live" and "You're a Very Lovely Woman" — the collective recorded output of the Merry-Go-Round reveals principal songwriter Rhodes to have been a keen student of '60s British pop music and charts his evolution as an increasingly potent practitioner of the form. But, in true rock and roll fashion, infighting and creative differences led Emitt to disband the group in early 1969, allowing him to pursue solo endeavors. After a planned solo offering by A&M records was shelved, Emitt decided to take matters into his own hands. Purchasing an aging second-hand Ampex 4-track machine in late '69, the nineteen-year-old retreated to his parents' garage to construct his masterpiece.

Today there is nothing unusual about a guy with a 4-track machine recording an album in his garage. In 1969, this was extraordinary. That an album like Emitt Rhodes should have emerged from such unlikely circumstances has only added to its legend. Upon its release in 1970, many insisted that it must be the Beatles. A number of enterprising disc jockeys and record store owners did little to dispel the illusion. And the thing was, it did sound a lot like a Beatles album. Wasn't that Paul McCartney singing? And those melodies, surely those melodies could have been drawn by the same hand that gave us "Michelle", "I Will" and "Blackbird". Half of the tracks could easily be snipped out and stitched into the running order of The White Album without sounding a bit out of place.

Emitt was quite proud of its domestic origins — the words "Recorded at Home" were actually engraved into the album's vinyl run-out groove by engineer Keith Olsen. Union rules at the time dictated that major label records must be recorded in a proper studio, so a "home recorded" credit couldn't appear on the sleeve. Emitt had even lobbied to have the album titled Homecooking, but the record company preferred the self-titled approach. And, happily, Emitt Rhodes was received warmly by both critics and the record buying public. Billboard called Emitt "one of the finest artists on the music scene today" and would later refer to his debut as one of the "best albums of the decade". The album began climbing the Billboard charts, eventually rising to #29, and the single "Fresh As A Daisy" barely missed the Top 40. Indeed, the future looked rosy for Emitt Rhodes, but then the bottom fell out.

Amazing as it may now seem, many recording contracts of the day demanded two albums per year — such was the case with Emitt's contract with ABC/Dunhill. However, the promotional performances required of Emitt, combined with the one-man-band recording approach, simply did not allow him enough time to deliver a second album six months after the first. His contract was thrown into default and he was actually sued by the record company for breach-of-contract — not the most conducive environment for creative pursuits. To add insult to injury, A&M Records decided to cash in on Emitt's newfound solo success with his new label and finally released the long- shelved American Dream album, complicating matters by confusing record buyers and detracting from sales of Emitt Rhodes. And though Emitt forged ahead, eventually delivering two more respectable albums, the stress of the ordeal had taken its toll on him and the music, and the uncanny pop sensibilities he had displayed on his debut often took a back seat to his disillusionment.

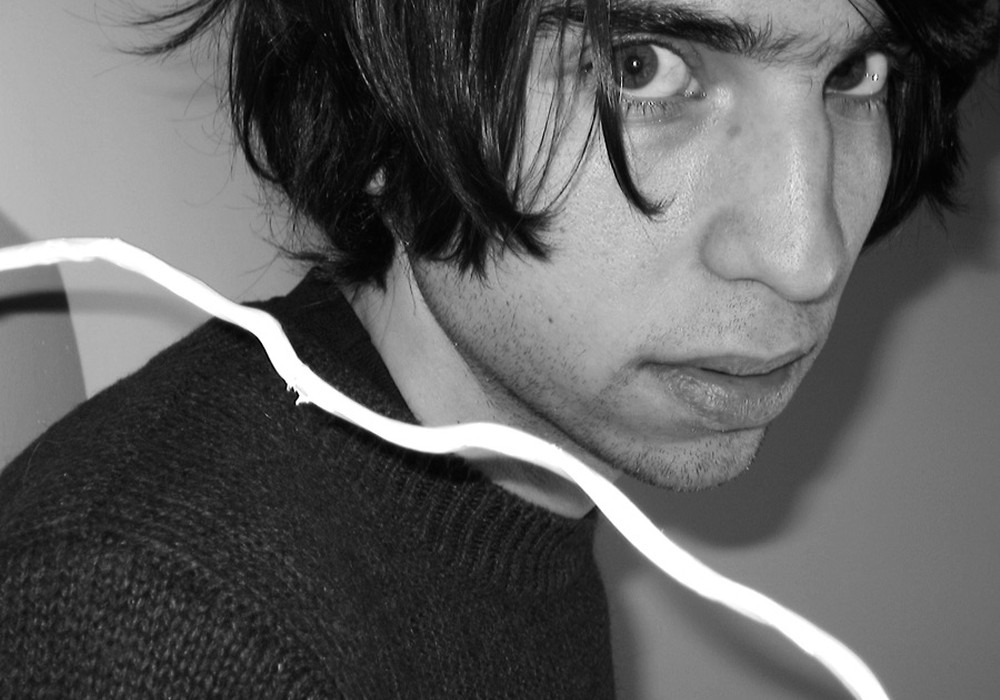

In 1973, Emitt bowed out of the role of recording artist, retreating instead to the safety of the engineer's seat, first as a staff engineer/producer/pre-production man for Elektra/Asylum and later opening the doors of his home studio to the public where he continues to work today. In fact, he bought the house directly across the street from his parents' old home where he had locked himself away in the garage all those years ago. Once again, he has converted the garage to a studio (albeit larger and more equipped), and it is here that we met for the following interview. His arrangement with the record company still has never been properly resolved, and getting paid what's due to him has been a long-term struggle. Reluctant to revisit the distant, but still painful, memories of his career as a "pop star", he was nonetheless happy to discuss how he recorded those albums so many years ago. Microphones and tape machines he doesn't mind talking about — they don't sue you and withhold royalties.

He still writes and records, but hasn't released a new song since 1973, a lamentable fact considering the formidable genius he displayed even before graduating from his teen years. Talk of a new album has been heard off and on for years, but so far nothing has materialized. Amidst the thirty years of demos accumulating dust in his studio surely lies the makings of another stunning collection of songs. And this time around, if he still so pleases, he can title it Homecooking.

So, how did you get into recording?

I had two stereo, reel-to-reel tape machines, 1/4". This was probably around 1966 or so — while I was still in the Merry-Go-Round. I'd set them up side by side, adjacent to each other, and I'd run the tape from the supply reel on one machine to the take-up reel on the other machine. I ran it through the heads of both machines, but what I did was twist the tape in between the first machine and the second.

Ah, yes, so you then were recording simultaneously on both sides of the tape.

Right. Just flip the tape and you've got four channels.

So how did that system work out?

Oh it worked just great! Yeah, it worked fine. Until the machines got moved.

Because if you moved one of the machines even a little bit...

Yeah, that was it. Any tapes you'd recorded would then be out of sync. But while they were in place it worked just great.

Did you record demos with that setup?

I guess I did. I don't think I recorded anything of note on it. Mainly it was just me getting experience with tape machines and overdubbing. And I had four tracks before anyone else on the block!

But when you were officially recording with the Merry-Go-Round, you guys were generally at A&M studios?

Oh, we recorded everywhere. All over town. But, yes, primarily at A&M.

You probably picked up a lot from all those sessions...

Absolutely. I learned how to engineer by being in the studio and watching. So when it came time to do it myself, I was familiar with how things worked. But being in the studio was a wonderful thing, watching the wheels go round and round, the big speakers...

At some point, though, you started buying your own recording gear.

Yeah, well that was after the Merry-Go-Round broke up. I had been kept on at A&M to record a solo album. Actually, it was just bits of leftover stuff, things from the Merry-Go-Round and some things I had done by myself in the studio. But it was all kind of assembled and called an album. Anyway, the album was finished and the label just kind of stuck it on a shelf at first, they didn't release it. So I started buying my own gear so I could record at home. This was around 1969. I bought an old Ampex 4-track machine, a huge washing machine-type thing.

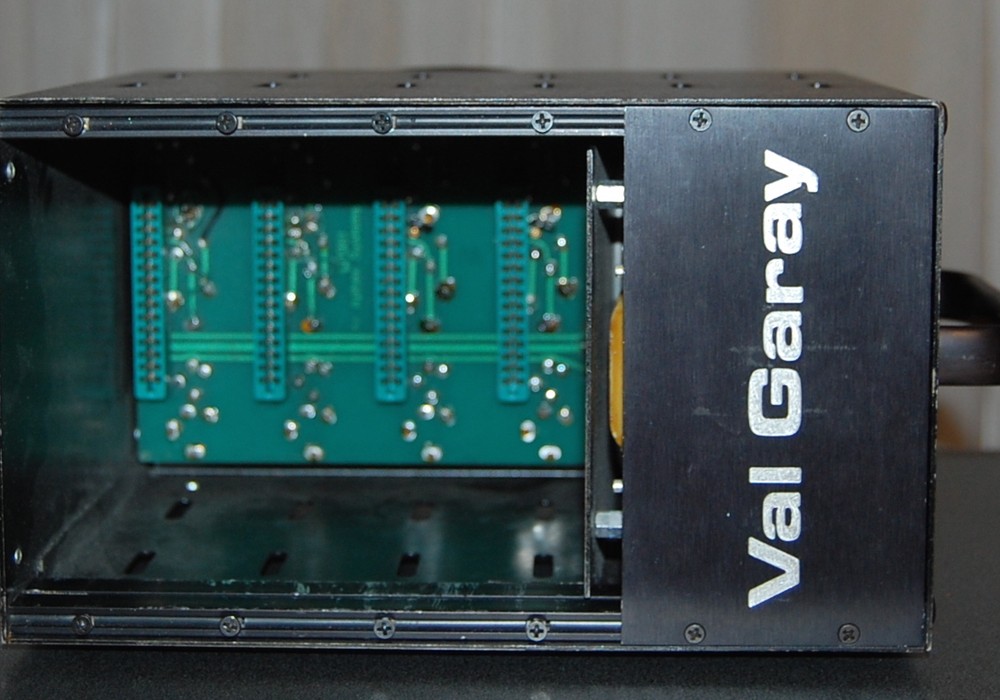

Do you remember what model it was?

It was an Ampex 300 with, I think, 351 electronics. It was strange, a custom job. The electronics were down below rather than on top, where they usually were. And it had some custom cabinet. But it was old. I mean, it was ancient even then! Like I said, it looked like a washing machine.

All tube...

Oh, yes. But it was a frustrating machine, I remember, because you couldn't record on adjacent tracks. Like, if I wanted to transfer track 1 to 2, forget it. You couldn't do that. You had to go from 1 to 3, so I had to plan out how to record everything so I could make sure I got it all on the tape. It required a lot of pre-thought.

So did you sketch out exactly what you were going to do on each track and when?

Well, what it meant was that I had to demo everything to see where it would go. Then I'd get serious and do it for real.

What other gear were you using besides the Ampex?

I had two little Shure mic mixers. Actually, they're still right here in my rack! I've kept them. They still work. They're Shure M67 mixers — real basic things.

I think they were originally made for news reporters and journalists to use while in the field.

Oh yeah, real rudimentary things. But they've got knobs and a meter and if you want to go stereo you've got two of them. Of course, at that time I wasn't doing any real stereo stuff, but we did simulate some stereo during mixdown.

Were you using any compressors or limiters at this time?

No, I...