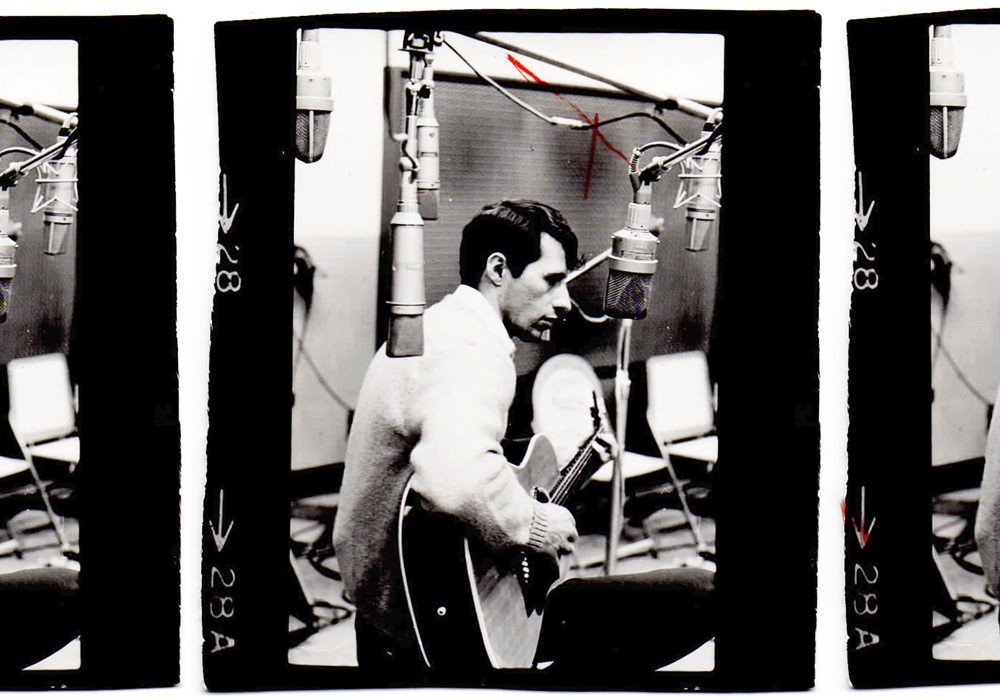

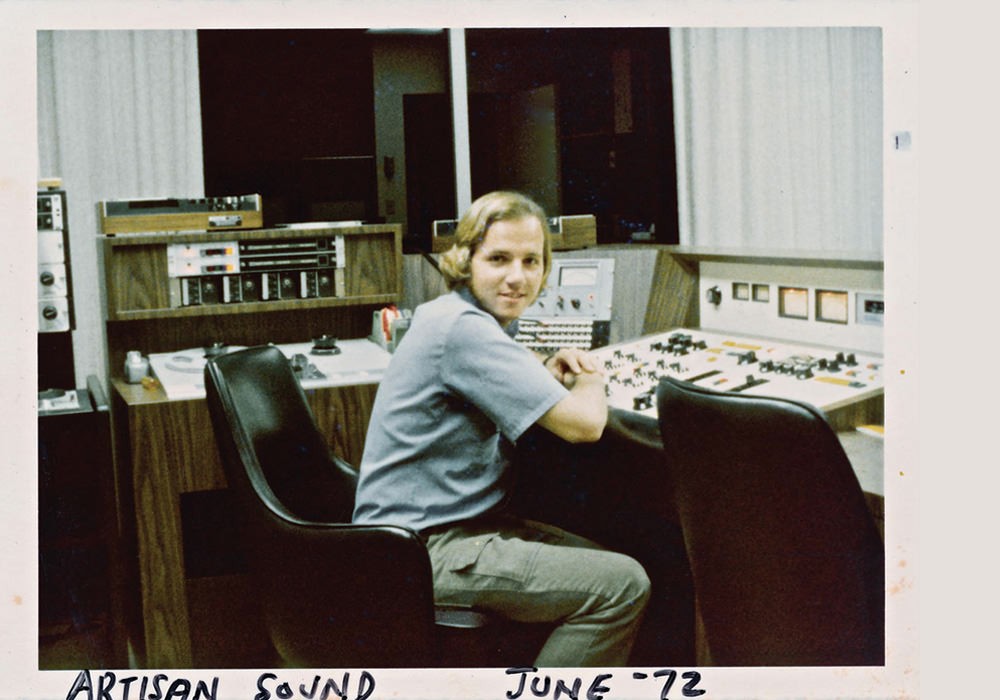

I first met Xopher Davidson in the late nineties at the Bloody Angle Compound studio, located in a corner of San Francisco that feels like nowhere. It is, literally, where the sidewalk ends, and, like in the Shel Silverstein poem, a place where the unknown is imagined. In this cold warehouse on the edge of the city (named for a Civil War battlefield that was the scene of the bloodiest hand-to-hand combat), I worked on programming computers for synchronized playback of multi-screen video, and Xopher worked on tracking, mixing, and mastering albums that were well ahead of their time with artists such as We, MixMaster Mike, Christian Marclay & Otomo Yoshihide, Iannis Xenakis, Mark Eitzel, Diamanda Galas, Tipsy, his own record vs. antimatter, and many other projects, mostly for release on the Asphodel imprint.

But what did he do outside of the cramped control room in the Compound? There is no way an engineer could work with all this gear and talent and not be inspired for his own work. As I expected, there was, and is, much more.

Amidst these hyperkinetic, cutting-edge productions, Davidson's own music, under the moniker "antimatter," seems almost unaffected by this activity, reflecting his quiet intensity, providing a soundtrack for his paintings and sketches. "This might seem odd," he comments on his listening habits, "but I don't really listen to much new stuff unless I'm working on it. I listen a lot to old vinyl and CD-Rs people hand me, so I always feel out of it when there's some new band I'm reading about in [a] magazine." A recent job mastering a local Mexican/Cuban synth-pop duo from San Francisco may mix what is hip and what is in front. "I think Pepito's new record, Everything Changes, is very fine and should be taking the world 'by storm' right now."

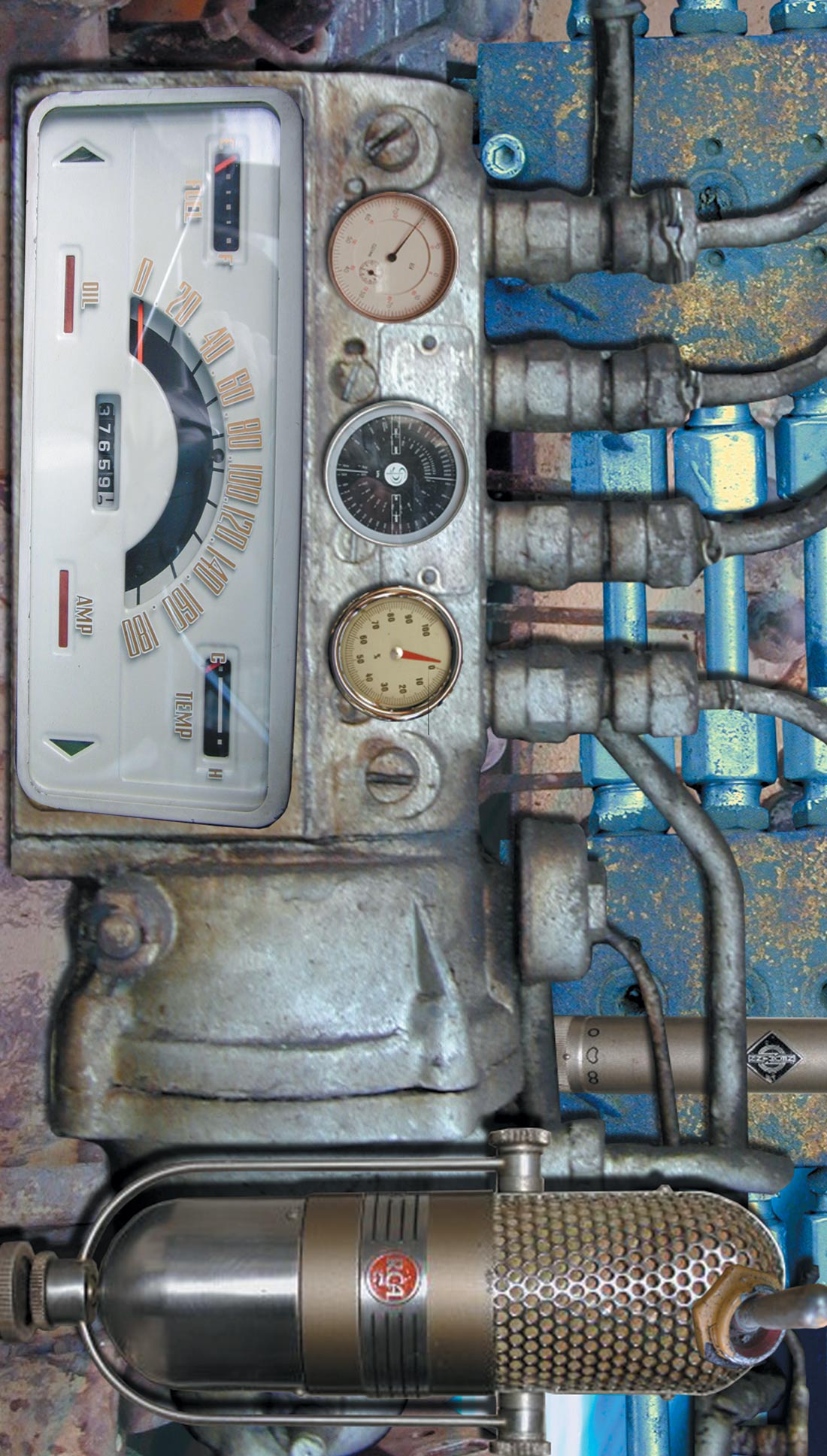

This listening vacuum is understood with a deep look in his personal "treatment center", littered with his paintings and photographs, modified thrift store masterpieces, Casios, semi-classic analog synthesizers and drum machines, toy noisemakers, military surplus, scientific castoffs, and music studio detritus that form the heart of his garage studio. The loose organizational principle behind most of the gear is the control voltage. Ranging from zero to five volts, this current is connected from one machine to another, warping signals into organic, living sounds, finally captured to a laptop. Such an open-ended process can be challenging to condense and finish. "When everything is possible and available it certainly becomes a question of what to exclude and when to end. I think it is instinct that says 'enough' or, I guess, when it stops gnawing away at you. Then the final master is burned and you are met with a rosy glow and a sort of slight depression at the same time. Ultimately, nothing but heartache."

Visually striking, the old military and scientific instruments stand out in the clutter of the treatment center. Large knobs in large boxes move actual gears and metal to translate a turn of the wrist into a frequency shift. "Mass is good. Weight, I think, comes across in the sound. Instability and drift, perhaps the last thing you want in your mastering chain, are assets to some electronic instruments. So, I'm quite happy when I can hear the electronics, and the artifacts of their design, as movement within a sound, like electrons washing along the banks of the river."

The CD Function Generator acts as the silent boatman on this river. Xopher teams with noise musician Zbigniew Karkowski (whose music once cracked the toilet in the Bloody Angle Compound studio when mixing for the 12-channel, five-subwoofer sound system), all fundamentals fall below 100 Hz. A recording felt as much as heard, only the occasional distortions provide a reason for your tweeters. It was "a record waiting to happen," he says. "Once you get...