If you’re a hip-hop fan it’s almost impossible not to know the name Mike Dean, as his sound is woven so deeply into the last quarter century of music. A low-key legend who prefers to let his music do the talking, Dean’s back catalog boasts Dirty South pioneers Scarface of the Geto Boys, UGK (Underground Kingz), Tha Dogg Pound, and Tech N9ne, along with Tupac Shakur, Jay-Z, and Travis Scott. Since 2004 he’s been the right-hand man in the studio, as well as on tour, with Kanye West. Sitting down with us, Dean hits rewind and takes readers on a rare tour back through the creation of some of his greatest hits.

courtesy of Moog

You were something of a musical prodigy growing up.

My sister and brother both played music; they both played saxophone and my sister played piano. My mother is an art teacher, and I think I was 8 or 9 when I started playing piano and saxophone.

Were there any instructors who played a special role in mentoring your musical development?

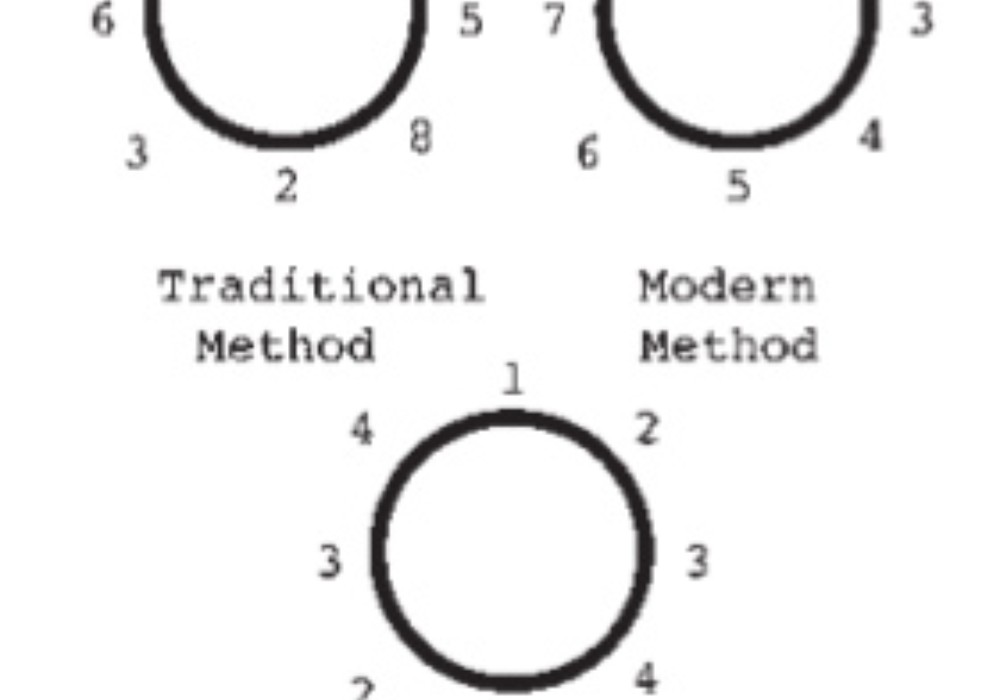

My piano teacher, Jane Ambuhl, was important in my musical development. I took piano lessons with her and she didn’t let me play by ear for years. [laughs] She wanted me to read music. My whole technique of playing came from her. She taught me how to hold my hands right, and I also took lots of music theory classes. She took me to the Music Teachers’ National Association competition each year, which I always won.

Are there any other musical styles, outside of rap, that were an influence on shaping your chops as a player growing up?

As a teenager I listened to classic rock like Pink Floyd, Bad Company, and Black Sabbath, but not really R&B so much. My first band, Freight, was in the ninth grade, and we played classic rock and Southern rock, like 38 Special and Lynyrd Skynyrd. To date all my bass parts are like old Cream; Jack Bruce.

How did you first discover sound recording?

When I was in my second or third band, they had a Tascam 4-track reel-to-reel and that was my first experience recording and overdubbing.

You got your start playing guitar for the Latin pop star Selena.

I’d known since I was a kid that I was going into music professionally. Once I started playing, that’s all I wanted. When I graduated high school in 1983 I had a scholarship to Eastman School of Music in Rochester and Berklee College of Music in Boston, but I had an offer to go out on the road playing for Selena that was too hard to turn down.

Touring with Selena at 18 must have been like a college education in and of itself.

It was all new to me. I learned a lot of new chords, and learned a lot of chord progressions. It’s a little different the way Mexican musicians interpret music. I played with her for three or four years, and I was really into that Latin music scene for a while; the Afro-Cuban and Cuban-style music.

When you left Selena’s band, what was your studio rig like?

I was 23 or 24, at that point, and had a couple of drum machines. My first was a Sequential Circuits DrumTraks and the Alesis HR-16. My first recording machine was the Commodore 64 [computer]. It changed my life because I could do eight tracks, which was a big deal back then.

Rap-A-Lot Records was your first gig as a sound engineer and in-house session musician. How did you first get your foot in that door?

Peter Reardon [owner of Shadow Hills Industries] was the Geto Boys and Rap-A-Lot’s in-house engineer, and I hired him to mix the Odd Squad [Fadanuf Fa Erybody] album. He told [Rap-A-Lot’s founder] James Prince about me. James put me on a weekly salary and in the studio to learn.

You worked closely with N.O. Joe, and the sound you two created together with Scarface took him to # 1 with The World is Yours album in 1993.

N.O. Joe came into Rap-A-Lot about that same time, and he was working with Scarface while I was working with [producer] John Bido. In my sessions with Joe, I was the engineer and he was the producer. He saw that I played a few instruments and started having me play on records; not as a producer, but just as a player. That led up to me starting to produce. Joe was the first one to show me how to play an [Akai] MPC, a sampling drum machine – all the drum machines before that had preset sounds.

How was the landscape different from producing hip-hop records today?

First and foremost, there wasn’t any sample clearance back then! [laughs] You could sample anything you wanted. There were no rules. We would change sounds up just enough to make it...

_display_horizontal.jpg)