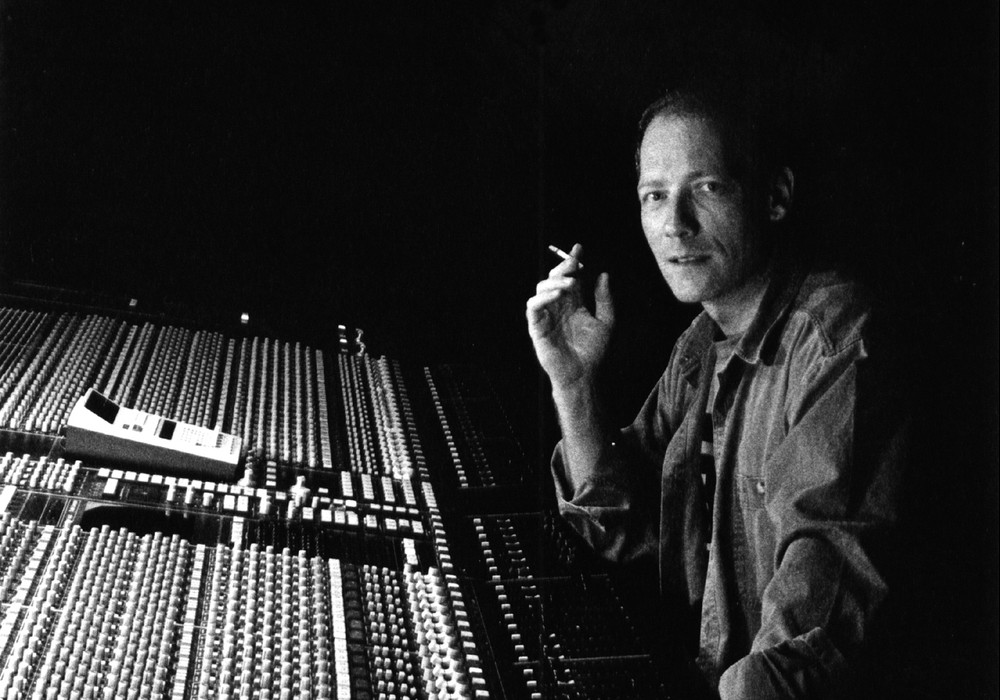

The career of Jimmy Douglass is incredibly interesting. Coming up at Atlantic Records in the early '70s, he learned the ins and outs of studio life on the fly while observing masters like Tom Dowd and Arif Mardin. In the '90s he began a long run of engineering, producing, and mixing with Timbaland on projects like Jodeci, Missy Elliott, Ginuwine, and Jay-Z. Not many recording folks can list credits as wide as Foreigner, Björk, Snoop Dogg, Roxy Music, Gang of Four, AC/DC, Donny Hathaway, and Kanye West. Jimmy's wisdom and open enthusiasm is obvious when you first meet him, and it's no surprise that he's been a big part of our sonic landscape for decades.

How in the heck did you end up as a teenager working at Atlantic Records?

A schoolmate of mine's dad, Jerry Wexler, was one of the owners of the company. It wasn't like I was chasing the record company, because I didn't know what Atlantic was!

Were you interested in music before that?

I played in bands, but the amount of information that was given to us... There were groups out there who had made it, but it was less information.

You obviously had to finish high school.

Atlantic Records had a studio, but I didn't have that job first. I got a job in distribution boxing records to put into the stores for an East Coast distributor. I didn't like that, but I learned a lot. I got to hear some really good product that I would've never heard otherwise. I was in a warehouse full of everything, and not all of it sold. I knew that, because of the repetition in my cart of all the orders for the stores. I'm like, "Buffalo Springfield? What is this? People keep buying this. I need to see what this is." I'd check them out. Back then, when you bought a record it was a big deal. From being so young and not having information, or being told, I learned so much. When I was working at Atlantic, the first session I ever walked into I didn't even know what a studio was. The first session I saw was Disraeli Gears by Cream. I loved them. Then they broke up, and they had this record that they put together with Eric [Clapton] and Ginger [Baker], Blind Faith. I remember they brought it to the mastering room, and I'm standing there going, "Wow! There are no pictures of anything. It's just 'Blind Faith.'" Madison Square Garden was sold out, and the record wasn't even out yet! How clever is that? They're mocking people, like, "You're going to buy this shit just because of who we are." It was incredible. Now you read about everything. There's no mystery anymore.

It really is different.

Everything is micromanaged and shoved down your throat in a certain kind of way. To find those little caviars like I was talking about, you don't find it anymore. It's all just fucking pushed into your face before you get to it.

Or the opposite side of that is that I'll work with young musicians who have access to everything, so they're listening to a really bizarre mix of music. In a cool way it's eclectic, but in another way there's a vague sense of focus for the artist.

Totally. There is none.

When you started working in the studio,were you an assistant initially? A runner?

No, Atlantic Records had no runners. We got assistants in the middle '70s, when the Rolling Stones and all the English bands came around and insisted on having assistants. If you were there, you did it, or you did something else. I worked with Arif Mardin. It wasn't like, "Hang out." It was, "Can you contribute? If you can't contribute, you shouldn't be here." Tom Dowd, the same thing. I watched him on [Dusty Springfield's] Dusty in Memphis album. He let me be there every night. That's where I learned how to use the board. He didn't teach me; I'd just be there watching. I'd shut up, so he wouldn't mind. I'd come in in the mornings and think back, "What was he doing?" I started doing what I saw him doing until I got my flow going. I kept doing it until I got to the point where I already knew what he was going to be doing. One night he was working and I was like, "Oh, here." He looked at me like, "Whoa! How did you know?" I was saving the good questions for him that I couldn't figure out. He has this reputation now, but [at the time] he was just some guy I knew. I thought everybody was as good as him; I didn't have a bar. I'd collect all the things that I didn't know, and come to him and be like, "Hey, this does this, but how come this doesn't do that?" He'd say, "How do you know this?" He hadn't taught me anything. As opposed to now, knowledge is so abundant, as we discussed. A lot of the younger folks walk in the door asking questions. It's like, "Shut up and listen. You're going to learn everything you need to learn." But that instant gratification thing? It's the opposite.

They might even come in these days and tell you how something should be done. Not even asking questions!

Don't even start me… Especially with the DAWs, the thing they don't understand is that they kept changing the shortcuts every time they came out with a new version. In the beginning, I learned them, but I can't keep learning them. You can do it the slow way. They go to college and they learn. They come into my session, and I'm doing it the slow way because that's the way I know how to do it. They go, "You know, there's another way to do that." I'm like, "I know. I'm not in a hurry."

I've had the same thing happen. I'm making records based on what I learned making them on tape; that workflow.

That's really important to me. That flow is part of that process, and how I think when I'm making records. That's not to say the way they're making records now isn't good. I respect it, and I've got to say it's much quicker in the short run, but in the long run it takes a lot longer. I don't give a fuck what you say; nobody ever commits. They're constantly going back. As you're doing that, your mind suddenly starts to reprioritize what's important. There is no "what's important" anymore. There is no discussion. Spending 50 hours on one little part; it's not worth it. "No, no. It's got to be right!" "Okay. Back in my day we didn't have 50 hours to do a whole fucking project. Doing the part you're doing right now is not going to be the difference as to why it sells or not."

What do you see now, like when you're working on something like Jay-Z's last record [4:44]? I'm sure there are 100 tracks or more on songs, and a lot of producers and ideas have funneled into these projects. How do you help keep your eye on the prize when mixing?

I think one of the reasons people call on me is because I'm the guy who comes in and goes, "Don't look here, don't look here, and don't look here. Here's the meat and potatoes. All the rest of the stuff you're doing is seasoning." It may be, and it may not be. Depending on how much time and focus we have, at the end of the day the main menu is what I came to do.

Focusing in on the heart of the song and what matters?

"Look, we're having steak and potatoes. We have parsley, or whatever, but the bottom line is we're having steak and potatoes." They spend all their time saying, "Oh, that parsley leaf is hanging out wrong." Nobody's going to even eat the parsley.

How was it working with No I.D. on 4:44?

Our dynamic is very interesting. Ernest [Wilson, aka No I.D.] is one of those people who knows history. We have a lot of fun with that. I've been doing this for a while; the old way and the new way. I'm still hanging in there making relevant records. I'm doing The Internet and really cool groups. I'm always trying to improve myself and go into forward mode to understand how things are being done. With Ernest, he's always saying, "No, man. You know the 'real' shit that I want to know." I'm like, "Dude, that's laborious." He says, "No, no, no." Every time he draws me out; he'll present a piece of old gear. "Look at this." I'll go, "Oh man, that's…" He'll say, "I would have used something else. See? That's why you need to be doing it."

My friend was helping him at United [Recording Studios], and he was amassing a lot of gear.

He's got gear I've never seen, or even heard about. It's crazy.

There are plug-ins now, but what is it sometimes about certain pieces of equipment that's going to spark something for you and me?

It's not predictable. It's the random occasional mistake that creates the magic. That's what they do that plug-ins don't do. The digital gear has accidents now and then, but with the analog stuff it'll be a smooth accident, where it makes you think differently. You can't get it back again; it's not recallable. That's what makes it special. While you're chasing that, you create something else.

I recently realized that you produced Solid Gold for Gang of Four in 1981. How in the heck did you end up with that job?

I did that record in London, at Abbey Road's Studio Two, where The Beatles worked. That was so good. When I was offered that job, my manager was a guy named Bud Prager, who used to manage Foreigner. I mixed a bunch of those Foreigner records, and I was saying to Bud, "Since you didn't pay me right, the least you can do is manage me."

"Get me some work!"

He got me this gig. I listened, and I was like, "Holy shit. What the fuck would I do with a band like this?" It was just so out there. On that Monday I had to have an answer, and that weekend John Lennon was shot. I'm a really good friend of May Pang's [a former girlfriend of Lennon's]; she lived in my building. I felt it through her, and I was so confused. When Monday came, I said, "I'll do it." It was such an experience. I was trying to get them to write more [a more] commercial and accessible [project]. They were writing about rich schoolboy subjects and politics in London. It was like, "We're never going to sell any of this." They said, "We don't care." Every day I'd be cramming that shit down their throats. There was a guy on the couch who sat in the back; I didn't know who he was. I saw Hugo Burnham, the drummer, recently. Hugo told me, "The guy on the back couch was Mick Jones of The Clash! He went and listened to everything you said and made those records." I said, "Okay. At least somebody was listening."

Gang of Four had a pretty staunch vision, like, "That's how it's going to be," with that band. Those first two records are really a certain style.

With that band, I said, "There are four of you and one of me. Here's the democracy. We'll vote on whatever's supposed to happen." If one didn't like it, it didn't happen. I didn't care if it was four to one. I had a lot of fun with those guys; I also learned a lot about producing and dealing with people who didn't want to do it my way, which is very difficult. In America, you want it done your way. The English are different.

That seems like an unusual project for you to end up on.

I think part of that was the fact that I'd worked with Andy Johns [Tape Op #39] on Television's Marquee Moon.

You helped him mix that. Was your role assisting?

Yeah. Since we didn't have assistants here's what went down. At Atlantic Studios, I got paid whether we did anything or not. There was a period where I was sitting there; I didn't have any real gigs. They were like, "Jimmy, there's this guy from London coming. Can you help him out?" I'm a proper engineer, at the time. I was like, "What the fuck. You're paying me, whatever." We had Studio B and Studio A. Studio B sounded like fucking dogshit. Nobody knew how to work it. We were a basic R&B, jazz, and funk studio. Every now and then we'd get some rock in there. The sound of B was so weird; nobody could get it. Andy comes in, and in my head I'm like, "Here comes this English hotshot. What the fuck does he know?" First of all, he's Andy Johns; he broke me the fuck down. You know Andy, right? You've met him?

I talked to him on the phone once. It was interesting!

He had that English flamboyant thing that makes you love him. He comes in, and I'm like, "Look at this guy. Is this the guy who's so famous?" He starts recording and doing this mix, and I'm listening on the big speakers and going, "That sounds like horse's ass! This is the guy?" He kept doing weird shit; he's EQing backwards and doing everything backwards. He says, "I'd like to hear this in the mastering room." I'm like, "Why?" In my head, it sounds like shit. We go up to the mastering room and the shit sounded unbelievable. I said, "That's not what I just heard down there!" But the bigger picture he taught me was how to hear out of that room. From that moment on, I had the key to mixing in that room. It was Andy. I thought it was amazing. There was a certain way the speakers had to sound to make it right, which isn't normally the way that we'd perceive it.

Had he listened to some other references before that to get a grip on it?

No, he just jumped right in. And a lot of bottles of beer!

Yeah. I interviewed Richard Lloyd of Television [Tape Op #56]. He was like, "The first thing Andy did in the studio was order a couple of cases of French wine."

Talking to you, I'm realizing I've had some blessed experiences.

If you look at the more traditional Atlantic Records projects, you were seeing all sorts of sessions.

I was doing all this work. Basically we were not allowed to fail. It was just an unwritten law. "You're here because you don't fail."

Did you see other people come and go back in your early years at Atlantic?

No. There was this one English guy, Adrian Barber; he used to do Cream. It was too much for him. He just kind of wigged out and walked away. Tom Dowd left really early to go with Jerry Wexler, and Arif Mardin was kind of left in house. We had another local kid, Gene Paul, hired as an engineer. He's the son of Les Paul [Tape Op #50]. He was older than me, but everybody was older than me! Ahmet [Ertegun, Atlantic's co-founder] hired him and was giving him all this work. It's like, "Hey, I was here!" Sometimes I'd end up working with Arif to help mix a record. He'd say, "Mix this record." He'd sit there and go, "What do we do with this thing?" I'd say, "What are you asking me for? I don't know what to do with this." We'd sit there together, just grabbing knobs to see what worked. That's how you learned at Atlantic Records.

The best school ever. You kept busy doing a lot during the '80s. Did you go into a little bit of a break, doing more post-production and jingles?

It wasn't by choice. It's more like music changed, and what I offered was unnecessary. Plus, I didn't have the vision of the new music.

In what way?

It was rap. Based off of what? To a man who sits there in a studio, spending hours getting a great drum sound, and then someone walks in the door and puts a record on and talks over it? I'm sorry. What the fuck? It sounds like crap because they got it off a record; there's noise. All the things I strived to be so excellent at, they were anti-that. And what they were talking about – their experiences in the hood – to me, that was not my experience. I didn't grow up in the hood; I grew up in suburban Great Neck, Long Island, in Kings Point. None of that experience made any sense to me. I didn't have the vision of what was gathering in front of me, so I became inefficient.

But you've come back around and worked with Timbaland and Jay-Z.

I taught myself the Synclavier [sampler]. Atlantic owned one, but no one knew how to use it. Pro Tools showed up after that. I kept moving along with the technology, the drum machines, and the keyboards. I just didn't know what to put it in; I didn't have a reference. I ended up out of work. I'd also left Atlantic Records. I got a partner; we got a tape machine and started hitting the streets as producers. We were trying to sell some songs to people. They were like, "That song is really cool but get another singer, and we'll give you a deal." We got a deal as an act, but when it didn't happen...

A lot of energy can go into that kind of project.

And a lot of money. I was funding myself for three years. I had a family to support. I even stepped out of doing all that for a minute, but somehow people wouldn't let me go. "Hey man, come do this record." Then the Jodeci session happened for me in Rochester, NY, which is where Timbaland was. They said it was going to be a four-month gig; instead it turned into two years and the emergence of a whole new thing.

Timbaland seemed to have a real vision for how he wanted to present the music. Was that something you started to figure out?

No, it was the same concept as Atlantic. In Rochester, there was this "factory" going on. There were 18 acts up there with [Donald Earle DeGrate Jr.] DeVanté [Swing, of Jodeci] kind of in charge of it all. There were two of us engineering. I was trying not to burn out. "I can do this, because I've done this." They had one analog machine upstairs and one reel-to-reel digital machine. I would have done two analog decks, if I could have. All the tracks we're doing on analog, and then all the vocals we put on digital and then sync'd up. That's how we were making the records. That Timbaland sound, a big part of it was basically tape compression. I was hitting the thing so hard. We must have made about 300 records in those two years – we were making them every day. That became the sound, just smashing the tape.

There's a sound that happens with the limiting on tape.

That wasn't saying we were going for that sound. It happened to us, and we knew how to let it be. People don't know how to let shit be now. Because we can go back, we'll just do it again and take away the magic of it. That was the era – that was the mistake. I grew up in a world where time and energy is all about the moment. The moment's more important than all the rest of it. When you try to go back and recreate that moment, that's when the magic just gets worn away, piece by piece.

These days you have the Magic Mix Room. That's your space?

Yeah. Down in Florida.

Are you working partly analog and partly digital for your mixing jobs? I mix all the time too, and I wonder how do we do the amount of recalls people want? I call them "breadcrumb trails;" I want to be able to go back, if needed.

Well, the thing is, you gotta go back. Every A&R guy in the world, they're all doing that. I got rid of my board last year. I had a Neve VR. I was finding that everybody on the other side of this process cared more about going back in and tracing the breadcrumbs, as you call it, rather than saying, "Wow, this is some extra special stuff. The sauce is amazing here." They don't give a fuck about the sauce. They just want to be able to go back and change things because somebody said that this thing over here is not good. "Change it." "Well, I did 15 things to get to that point. Okay. It's going to take me all day." Then you do it and they go, "That's great, but now go back and change this." I can't keep doing that. It was interesting, and I was excited about it. It's like playing a solo for the first time. Then you play the same solo again and again; it's lost its magic. If that's what's more important to them, the duplication of that solo, I'll stay in the box. I can do anything they want me to do, at any time, and I won't have any resentment about it. It'll go a lot quicker.

It's hard to keep the enthusiasm and perspective that we start with on a mix. When I start getting micro-managed afterwards, sometimes I just lose the vision for my mix. How do you maintain perspective through this process?

One of the great things about working with Timbaland is that I was producing a lot with him. "Here's this." I would do what I do as a producer, like I would do the vocals for him. He'd have his input, but he'd let me do it. Sometimes we'd come to a part where I'd think this and he'd think that. Well, guess what? "You're the producer. It's your call." I've learned how to do that. A&R people and so forth are like, "This would be really cool. We don't want that." I'll say, "Okay, no problem." It's not like back in the day, when I'd fight and say, "You're wrong," and we'd be in the trenches. Now it's like, "Okay! You're driving the train." I don't have a problem with it. "Let me help you do what you're doing the best."

But our views become a little more analytical and a little bit less "gut feeling" as we're working this way.

It's out the window. Part of the reason is also because you can go back in. Because you can go back, your gut doesn't matter. When you had to commit to tape or something, it was all about the gut. You're rolling dice, one time.

I was erasing tracks the other day on tape. "Let's make sure it's the right track!" There were butterflies in my stomach. "What if I do the wrong thing and erase the kick drum?"

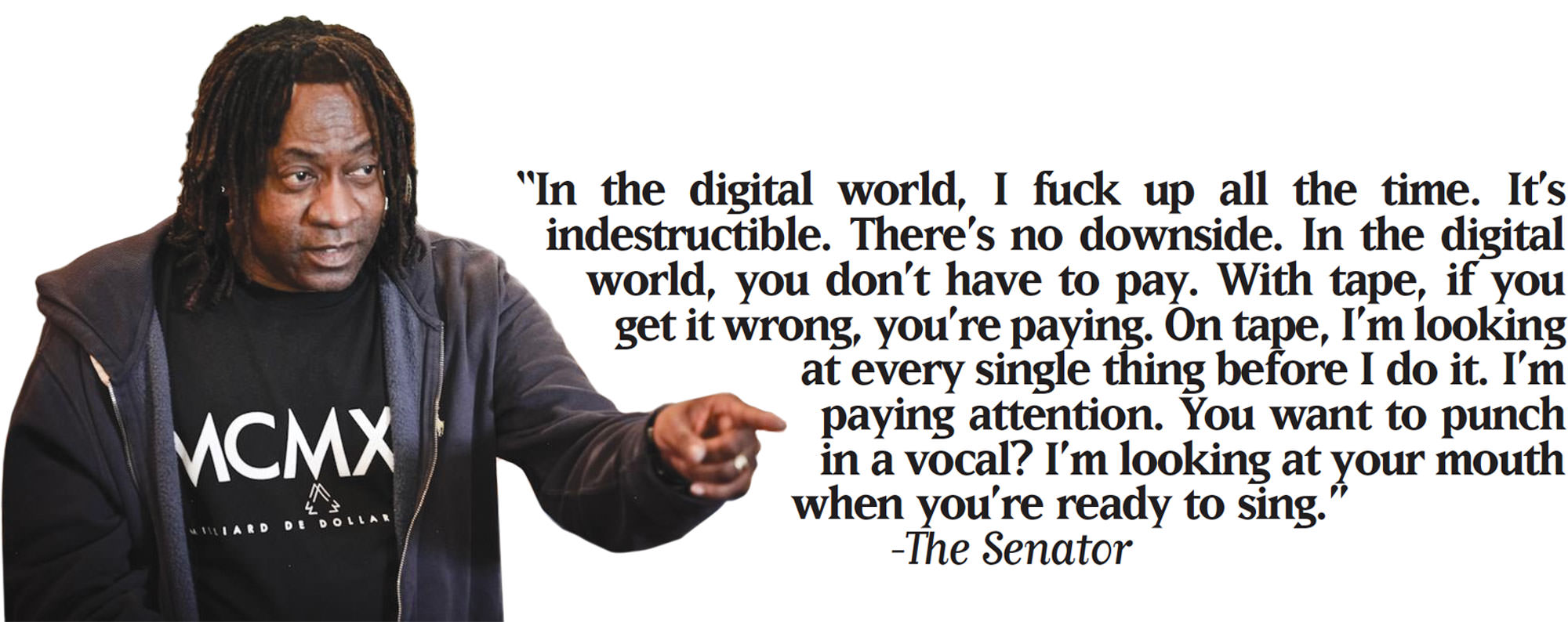

You know what's interesting about that? You're right, there are butterflies. But when that's all there was, you had no time. My thing was this; I have no time for you to have butterflies. If you're in the room, I know you're not going to erase any of that or you should not be there. That's how I always thought. In the digital world, I fuck up all the time. It's indestructible. There's no downside. In the digital world, you don't have to pay. With tape, if you get it wrong, you're paying. On tape, I'm looking at every single thing before I do it. I'm paying attention. You want to punch in a vocal? I'm looking at your mouth when you're ready to sing. I can't say, "I thought you said you wanted to punch in here." Missy Elliott does that all the time! Fortunately, it's on digital. "Punch this in." I go boom. Then she says, "It's not there!" "But you said, 'There,' Missy." Man, I'd get pissed at her. You want to communicate, you gotta communicate!

I've been there with artists!

When she was coming up, Missy would do some of the craziest stuff and make me nuts. First of all, we're up in Rochester and there's no help anywhere around. We've got this Neve VR console. She would take drinks and set them on the console all the time. I'd say, "Missy, please don't do that." One day she does it, and I yelled, "Missy, take the drink off the console! We're in the middle of nowhere. If that thing goes in the thing, it'll blow up." She's like, "Calm down Jimmy." The reason to me that that's a funny story is because once she blew up [fame-wise], she'd come in and put drinks on the console, and it's like, "Okay, not a problem. Not a problem!"

Oh, man! I still want to pick your brain about Jay-Z's 4:44. That record really kicked my ass. What kind of a mixing process was that for you?

The first part that was interesting was the dynamic with Young Guru [Gimel Keaton], Jay-Z, No I.D., and me. I'd never worked with No I.D. before. We'd been trying to work together. Jay-Z and I had worked together on many records – we know each other. You've got a dynamic with all these people. "What's your contribution, Jimmy?" Somebody said, "We want to print to analog and mix it." Somebody put me in a studio that Jay-Z didn't ask for – it wasn't No I.D.'s studio. I'm like, "I can mix in any studio." Then Jay's like, "You like this room?" I'm like, "It's okay." He's not feeling the room, but I didn't really know it. Then it's like, "Oh, he's not feeling the room so this isn't going to work." It's like, "Why aren't we in No I.D.'s studio?" "I didn't know he had a studio. Why aren't we over there?" It was that kind of party. We couldn't get people to align the tape deck. You think I'm kidding? Go to L.A., and go to most of the studios and say, "I have a tape. Who can align it for me?" It's a dead art.

Last time I was down there I couldn't get the tape deck to rewind at the place I was working.

I'm not going to mention the name of the studio, but the kids I was with had never seen a tape machine, so it was on me to remember how I used to align a tape machine before I even started mixing. Then when I transferred it, "This is not what the rough mix sounded like!" This is what I've learned in this "new world" we've been discussing. Everyone wants to hear what they've been hearing. "I've been listening to that for the last month." When I finally settled in, mixing was really simple. They picked what they wanted. It was a matter of expanding what they had without trying to be the star. I did start trying to make the kick just kick ass – I've got to make my contribution somewhere. Then Jay came in… it was one of the only comments he ever really made. He said, "The kick doesn't fit in the record." I said, "What do you mean?" He said, "Listen to it. It doesn't fit in the record." I was like, "Oh!" I was making it so important and so fucking kickass, but that wasn't what the record was. When he said that, I was like, "I need to reapproach this record. I need to make myself fit in the record, and then enhance and expand it." Don't change the main menu.

It's a words record.

It is a words record, and it's a delicate record. You don't want the kick competing with Jay-Z on the dance floor. The man's begging to his wife for forgiveness. It's a very sensitive product, man.

How do you go about creating plug-in presets, like for the UAD Neve 88RS Channel Strip?

Oh, it's really simple. I'm not really trying to put anything across. I'm busy working. I end up where I end up because I end up where I end up. Does that make any sense? I'm just trying to get from here to there, and I happen to go over here to get there, unlike some of my compatriots, who are amazing. When I sit with Tom Lord-Alge, he said, "I'm going to do this, and it'll be this, and then that." I watch him, and I'm like, "You're so fucking good." But that's not how I work. It's that Atlantic upbringing; there was no teaching. You'd need to come up with a record at the end of the day, and that's all we cared about. It's the same thing. "That kind of works. That sounds better. Okay." I use my ears a lot, and people [generally] don't [do that] anymore. They use their eyes and their idea of what somebody else did, thinking that it fits their model. There's different caviar man, all over the place. It's still caviar, but you don't treat it all the same! That's how I do it.

Where'd you get the nickname "The Senator"?

When we broke out of Rochester, we'd already done Ginuwine's song, "Pony." I was going to help Timbaland. I knew all these people in New York, because I'd been doing this forever. They were brand new and didn't know anybody. What I'd been hearing for the last two years was this Timbaland style, and I was sitting there thinking, "This is incredible, and nobody knows about it." I went around to get him the deal for Ginuwine. When we were doing the record, there was Ginuwine, Timbaland, me, and Robert Reives. Rob, being a younger person, said, "I'm going to help you get your thing moving, man. You can't be Jimmy Douglass." I was like, "Why not?" Rob says, "You can't just come back and be the same guy that you were! That doesn't work." I was like, "Really?" He said, "Yeah, man. You gotta get something else." I remembered on one record where some guy called himself "Commissioner" [Gordon "Commissioner Gordon" Williams]. They said, "You should be 'The President.'" I was like, "No, that's too fucking much. But I could do 'Senator.'" At the end of the day, this record business is so fucking political! That's where it stuck.

_display_horizontal.jpg)